Dynamic Pricing Algorithms

Dynamic pricing is a type of pricing method that adjusts prices for items based on real-time market conditions.[2] This is typically achieved by using algorithms inputting variables like competitors' prices, supply and demand quantities, customers' demographics and personal preferences, seasonal factors, and more.[3] As a result of the growth of the internet and consequently an increase in online transactions, a variety of industries utilize dynamic pricing as part of their business model. Common industries that implement dynamic pricing include advertising, entertainment, sports, airline travel, utilities, and the e-commerce industry as a whole.[4] Dynamic pricing can allow companies to collect greater profits because of rapid price adjustments, but sometimes raises ethical concerns related to areas of data privacy, social inequality, information integrity, and antitrust issues.

Contents

History of Dynamic Pricing

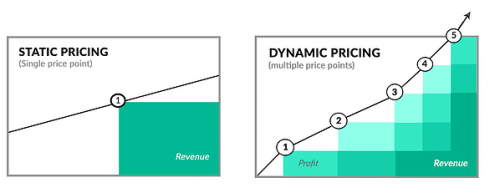

Before Dynamic Pricing: Static Pricing

Before the advent of dynamic pricing, sellers primarily used a form of static pricing. Static pricing refers to when a company sets a price, and then keeps the price “static” regardless of the demand and supply conditions within the market.[5] Static pricing allowed companies to establish price reliability and guarantee profit minimums, but wasn't very effective at adapting to changing market conditions. Early critics of dynamic pricing emphasized how uncertainty around changing prices could harm business because customers would lose trust in companies, it could potentially waste customers’ time to travel to the store, and because of the effort required to manipulate prices.[5] However, the vast majority of these doubts were dispelled by unanticipated improvements in modern technology: high-speed computers and the growth of online shopping quickly enabled micro-price-adjustments and decreased the “distance” between retailers and customers.

The Growth of Dynamic Pricing

Dynamic pricing primarily grew out of two areas of research: statistical learning and price optimization.[6] Statistical learning refers to how dynamic pricing algorithms are able to adjust prices based on numerical data collected over time, and price optimization involves calculating prices that maximize revenue for a business. In the late 1970's, the airline industry was one of the first main players to use dynamic pricing as a result of more relaxed legislation from the United States congress.[7] Up until that point, the prices of airline tickets were set by the government. When the federal government gave airline companies autonomy over ticket pricing, dynamic pricing was developed in the industry. With the advent of the computer revolution, dynamic pricing has grown increasingly complex. Although early dynamic pricing was mainly based on supply and demand conditions within the market, modern applications can use highly complex variables like customers' purchase histories and locations to make both small and large adjustments in prices.

Modern Prevalence of Dynamic Pricing

Dynamic pricing has grown extremely prevalent and is now used in industries ranging from e-commerce and entertainment to ridesharing. As a result of large retailers like Amazon embracing dynamic pricing, other companies have been pushed to develop similar pricing strategies.[8] A research report from Bain & Company details how although once used more as a defensive move to react to market conditions, dynamic pricing is now often used as a proactive tool to better generate profits and find new customers.[8] In the current market, companies can even purchase dynamic pricing software from third-parties, which saves expensive research and development costs; Repricer.com and Antuit are examples of companies selling dynamic pricing software.[9] Overall, data shows that retailers utilizing algorithms and dynamic pricing experience greater success in sales.[9]

Main Types of Dynamic Pricing Algorithms

Segmented Pricing

Segmented pricing is a type of dynamic pricing that assigns two or more varying prices for the same product based on a specific "segmented" customer group.[1] Segmented pricing can also be carried out without algorithms; for example, movie theaters may charge different ticket prices to children, adults, and seniors. However, modern dynamic pricing algorithms can automate this process, utilizing variables like customer age, gender, location, and more to alter prices. Therefore, modern segmented pricing can involved more precise "buckets" of customers because of the greater amount of variables that can be considered by algorithms. For example, a business might charge a customer more based on geographical data that demonstrates a higher willingness-to-pay.[10] Segmented pricing has historically sometimes raised privacy concerns due to its usage of customer data, especially when algorithms and data usage are not transparent.

Time-based Pricing & Peak Pricing

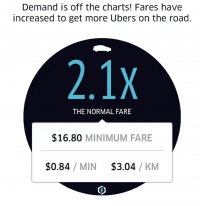

Time-based pricing is a type of dynamic pricing that alters the prices of goods based on time-based factors like months or seasons.[1] Common examples of this type of dynamic pricing include airline tickets being more expensive during the holiday season, or utilities prices being more expensive during certain months of the year. Peak Pricing is closely related to time-based pricing, but is also related to demand for a said product or service; essentially, peak pricing algorithms will increase prices if there is a greater demand for a good or service in a set time frame.[1] The most common example of peak pricing is typically Uber, which charges customers increased fares during high demand times: "surge pricing".[11]

Competition Pricing

Competition pricing is a type of dynamic pricing that compares the prices that rival retailers charge for similar products, and then recommends a price for a business to charge for a product. According to the Brookings Institute, this type of dynamic pricing has grown increasingly sophisticated, with algorithms even available from third-party vendors.[12] The main advantage of competitive pricing algorithms is their speed, which allows companies to quickly adjust prices in response to competitors. In fact, studies have proven that retailers who are in possession of faster dynamic pricing algorithms are able to have lower prices on average when compared to competitors.[12] There has also been some evidence that competition-based pricing can lead to higher prices for consumers as a result of companies intentionally raising prices in order to avoid losing market share to undercutting competitors with speedier algorithms.[12]

Examples of Industry Usage

A variety of industries have implemented dynamic pricing over the past couple decades, especially with the rapid growth of the internet; some major examples are the rideshare, retail, and entertainment industry.

The rideshare industry is a major example of an industry that has benefitted from but also has largely been built on dynamic pricing. Popular rideshare companies that utilize dynamic pricing include Uber, Lyft, and Didi Chuxing.[13] Although dynamic pricing has raised some ethical concerns related to inflated pricing during emergencies, it has also served as a tool that efficiently matches the demand of customers with the supply of drivers.[13] For example, Uber's “Surge Pricing” presents customers with the option to either pay a higher fee or wait longer, which can serve to effectively manage the system during crowded times.[11] As a result, the rideshare industry’s usage of dynamic pricing has allowed a level of supply-demand-matching that was previously unseen in the taxi industry, for example.

Retail Industry

The retail industry employs various types of dynamic pricing including adjusting prices based on the number of items being sold, the amount of web traffic, the time of day or year, or even the competition from other websites. [14] Examples of popular retail giants that use dynamic pricing include Amazon, Walmart, and Target.[15] Dynamic pricing is a popular pricing tool among retailers because they can apply the tool to more “stable” products like groceries, but also to more seasonal products like clothes.[15] Compared to brick-and-mortar retail, a shift towards online shopping has allowed retailers to move away from fixed prices to more rapid, algorithm-based, and competitive dynamic pricing.

Entertainment Industry

Dynamic pricing is also extremely prevalent in the entertainment industry; sports tickets, concert tickets, and movie tickets are all examples of goods that are often priced using dynamic algorithms. Dynamic pricing in the entertainment industry is often based on the level of demand for a good, as well as the time at which the goods are bought. Platforms like Ticketmaster have used dynamic pricing to increase prices for more in-demand tickets instead of setting tickets at a static price – Ticketmaster states that under static pricing, many tickets bought buy scalpers are resold on the secondary market for higher prices.[16] Although Ticketmaster’s dynamic pricing may help music artists make more revenue that would have been lost on the resale market, many consumers still dislike the system. While dynamic pricing in industries like rideshare may result in smaller prices changes, dynamic pricing in the entertainment industry can sometimes result in prices that are exorbitantly high.

Case Studies of Usage

Coca Cola

In 1999, Coca Cola CEO M. Douglas Ivester attempted to deploy Coca-Cola vending machines that used dynamic pricing.[17] Ivester was attempting to capitalize on company data that showed company's traditional vending machines sold a lot more coke in warmer vending conditions. According to the CEO, a dynamic pricing-based vending machine model that could charge more under hotter temperatures would be a profit-making machine. This announcement was quickly met with public outcry over concerns of price-gouging, and was never put into effect by the Coca-Cola company. The Coca-Cola case study is often cited when analyzing the effects of dynamic pricing on consumer sentiment; price fluctuations have been found to often have negative impacts on brand loyalty and image, which in turn can make people experience "customer betrayal" when prices of familiar products are altered.[18]

Uber

Uber has had controversies related to the app's usage of "Peak Pricing", which is a type of dynamic pricing that increases prices during times of increased demand, such as in a crowded area after a major event.[4] While this concept typically works, it has historically had severe negative impacts during situations like security emergencies or extreme weather scenarios. During a 2017 terrorist attack in London, a 2016 bombing in New York City, and a 2017 taxi drivers' strike in the United States, Uber fares increased as much as 500%.[4] Although raising prices during crowded times isn't inherently controversial, these instances have raised ethical questions about how dynamic pricing algorithms don't take into account factors like human health and safety.

Root Insurance

Started in 2015, Root Insurance is a personal insurance provider that introduced a novel way to measure customer's driving behaviors in order to calculate insurance risk premiums: dynamic pricing.[20] The company uses variables like braking strength, driving speed, and more. Root Insurance has explicitly claimed that they place an emphasis on not using variables in the algorithm that could create socioeconomic inequality: for example, education or occupation. The company also tries to make the algorithm as transparent as possible through usage of the Root insurance app, which breaks down the algorithm's weighting of driving skills, insurance fraud statistics, and more.[4] The company has also pledged to cease using customers' credit scores by the year 2025, which is a variable that some argue could increase inequities. This case study highlights how dynamic pricing has the potential to increase customer satisfaction: Root places an emphasis on price transparency, minimizing costs for customers, and customer relationships.[20]

Airbnb

Airbnb’s usage of dynamic “smart” pricing is a unique case study because the Airbnb hosts are essentially given control of the dynamic pricing option. According to Airbnb, the main factors that can influence demand are daily trends, seasonal shifts, and special events in local areas.[21] Airbnb hosts are able to turn Smart Pricing on or off, and also have control over “fluctuation limits” or specific nightly prices.[22] Airbnb also offers a variety of dynamic pricing tools for hosts to utilize: price preview tools, promotion tools, and discount tools. Airbnb caters to two types of “customers”: hosts and guests. Therefore, the case study is a unique example of how a business can have a vested interested in both educating customers about dynamic pricing in addition to gaining profits from the tool itself.

Ethical Dilemmas with Dynamic Pricing

Dynamic pricing algorithms leverage customer data (often discreetly) to alter consumer prices and experiences. As a result, various ethical issues arise related to data collection & algorithm transparency, socioeconomic inequality, and business collusion & antitrust issues.

Data Collection & Privacy Issues

Ethical issues related to data collection and privacy are often associated with dynamic pricing, mainly as a result of the usage of algorithms. The algorithms that are used to collect customer data are often opaque to the customer themselves, which can create feelings of mistrust and "customer betrayal.[12] [18] Customer data like age, gender, location, and product preferences are often revealed without customer awareness, and in turn used to alter the prices that the customer pays; companies stand to profit immensely from decisions based off consumer data. Companies may also intentionally withhold access to information that could benefit customers, like price comparisons.[23] In 2000, Amazon faced public criticism when people experienced varying prices for goods based on their location and other personal demographic information. Although the company claimed it was engaging in price testing, the case study serves as an example of public criticism over potential personal data usage.[24]

Socioeconomic Inequality Issues

Numerous studies show that dynamic pricing leads to higher prices on average. This is a result of multiple sellers in a market charging above the recommended retail price in order to account for the fact that they will likely be price cut by another company using an algorithm: this is known as "Supracompetitive" pricing. Data shows that less than 20% of low-income individuals in the United States do a significant amount of shopping online; higher prices as a result of dynamic pricing disproportionately harm low-income individuals in the United States.[25] As the e-commerce industry continues to grow, ethical issues related to socioeconomic inequality arise: Low-income consumers will be pushed away from online shopping as a result of dynamic pricing algorithms and high prices. This could potentially increase the economic divide between high- and low-income individuals in the United States.

Issues of Access to Essential Products

Dynamic pricing can also cause ethical issues when affected products are considered “essential”. Items like food, medicine, and face masks are examples of items that could be in immense demand during times of crisis, and could be priced extremely expensive by a dynamic pricing algorithm as a result.[23] However, a lack of access to these items could end up causing a lot of harm to customers. According to Harvard Business Review, dynamic pricing’s focus on “economic efficiency” can sometimes “block access to essential needs, magnifying the possibility of societal harms”.[23] This ethical issue can sometimes compound issues of socioeconomic inequality, because low-income customers are sometimes harder-hit when access to staple products becomes more difficult.

Business Collusion & Antitrust Issues

Although dynamic pricing allows companies to quickly adjust prices to competitors, there have been ethical concerns about whether firms could be intentionally working together to manipulate prices.[12] This would be anti-competitive behavior, which is considered illegal under U.S. law. However, because of the opaque nature of many dynamic pricing algorithms, there aren’t many legal guidelines that dictate what would be considered collusion vs. an algorithm responding to a competitor’s algorithm.[12] According to Harvard Business Review, “… competition among pricing algorithms allows firms to charge competitors supercompetitive prices even in the absence of collusion”.[9] Therefore, this example raises the question of whether the companies’ intent matters when determining antitrust law related to dynamic pricing.- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Fuchs, Jay. (September 7, 2022). "Dynamic Pricing: The Complete Guide" Hubspot Blog. Retrieved January 25, 2023.

- ↑ pwc.de. (June, 2020). "Ethical Aspects of Dynamic Pricing" PricewaterhouseCoopers GmbH. Retrieved January 25, 2023.

- ↑ Wakabayashi,Daisuke. (February 6, 2022). "Does Anyone Know What Paper Towels Should Cost?" New York Times. Retrieved January 25, 2023.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Bertini, Marco & Koenigsberg, Oded. (September 2021). "The Pitfalls of Pricing Algorithms" Harvard Business Review. Retrieved January 24, 2023.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Cachon, Gérard P. (December 2010). "Dynamic versus Static Pricing in the Presence of Strategic Consumers" UPENN Repository. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ↑ den Boer, Arnoud. (June 2015). "Dynamic pricing and learning: Historical origins, current research, and new directions" Surveys in Operations Science and Management Science. Retrieved January 24, 2023.

- ↑ Goldstein, Jacob. (June 17, 2015). "The Birth and Death of the Price Tag" NPR's Planet Money. Retrieved January 24, 2023.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Kermisch, Ron; Burns, David; Davenport, Chuck. (February 5, 2019). "Dynamic Pricing: Building an Advantage in B2B Sales" Bain & Company. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 MacKay, Alexander J.; Weinstein, Samuel. (2021). "Dynamic Pricing Algorithms, Consumer Harm, and Regulatory Response" Harvard Business School. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ↑ Brooks, Chad. (Jan 23,2023). "What is Dynamic Pricing, and How Does It Affect E-commerce?" business.com. Retrieved January 24, 2023.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Uber. "How Surge Pricing Works" Uber. Retrieved January 24, 2023.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 Brown, Zach & MacKay, Alexander (July 7, 2022). "Are online prices higher because of pricing algorithms?" The Brookings Institute. Retrieved January 24, 2023.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Yin, Yafeng (2016-2017). “Modeling and Analysis of Dynamic Pricing of Ride-Sourcing Services” Technologies for Safe and Efficient Transportation. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ↑ Shpanya, Arie. (May 14, 2013). "5 Trends to Anticipate in Dynamic Pricing" Retail Touchpoints. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 remi.ai. (February 10, 2020). “Companies That Use Dynamic Pricing” remi.ai. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ↑ della Cava, Marco. (August 17, 2022). "Springstreen tickets for $4,000? How Dynamic Pricing Works and How You Can Beat the System." USA Today. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ↑ Leonhardt, David. (June 27, 2005). "Why Variable Pricing Fails at the Vending Machine" New York Times. Retrieved January 24, 2023.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Buchh, Ziad. (July 25, 2022). "Online pricing algorithms are gaming the system, and could mean you pay more" NPR's Morning Edition. Retrieved January 24, 2023.

- ↑ Kosoff, Maya. (November 1, 2015). "Stop Complaining About Uber's Surge Pricing." Business Insider. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Clayton, Alex. (October 27, 2020). "Root Insurance IPO | S-1 Breakdown" Meritech Capital. Retrieved January 24, 2023.

- ↑ Airbnb. (2023). "Smart Pricing" Airbnb. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ↑ Airbnb. (2023). "Adjusting your price and settings to meet local demand" Airbnb. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 hbr.org (March 26, 2021). “How AI Can help Companies Set Prices More Ethically” Harvard Business Review. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ↑ Streitfeld, David. (September 27, 2000). "On the Web, Price Tags Blur" Washington Post. Retrieved January 24, 2023.

- ↑ Gralnick, Jodi. (December 19, 2017). "There's a wide -- and growing -- digital divide between high and low-income shoppers" CNBC. Retrieved January 24, 2023.