Difference between revisions of "User personas"

(→Ethical Concerns) |

|||

| Line 63: | Line 63: | ||

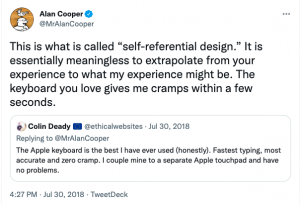

Self referential design was another criticism that Alan Cooper had called out, and he described it as “designing for oneself rather than for the audience.” <ref>Cooper, Alan, and Robert Reimann. About Face 2.0: The Essentials of Interaction Design. Wiley, 2003. </ref> Designers and developers who fail to extrapolate from their own experiences and design for themselves as opposed to users risk losing customers and creating a negative user experience. Similarly, to designing for oneself, designers can also design with a specific friend, family member, co-worker, or other closely related person in mind. To mitigate this, designers can consider avoiding names of people that the team knows and would subconsciously think about as the persona. | Self referential design was another criticism that Alan Cooper had called out, and he described it as “designing for oneself rather than for the audience.” <ref>Cooper, Alan, and Robert Reimann. About Face 2.0: The Essentials of Interaction Design. Wiley, 2003. </ref> Designers and developers who fail to extrapolate from their own experiences and design for themselves as opposed to users risk losing customers and creating a negative user experience. Similarly, to designing for oneself, designers can also design with a specific friend, family member, co-worker, or other closely related person in mind. To mitigate this, designers can consider avoiding names of people that the team knows and would subconsciously think about as the persona. | ||

| − | [[File:Alan-cooper-tweet|thumbnail|A tweet from Alan Cooper criticizing designs that don’t consider the experience of real users]] | + | [[File:Alan-cooper-tweet.png|thumbnail|A tweet from Alan Cooper criticizing designs that don’t consider the experience of real users]] |

Revision as of 23:35, 9 February 2022

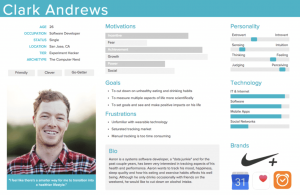

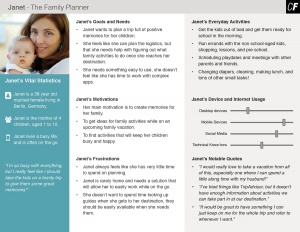

A user persona (also customer persona, user type, archetype) in human-computer design is a fabricated profile used to represent realistic aspects of the user or customer segment who are intended to use certain applications, websites, or other digital products [1]. Personas embody important aspects and help personify user data [2]. It is a type of research method that takes a diverse and complex audience and condenses all of their data into a few archetypes that sum up their needs and desires [3]. As a popular method of representing hypothesized users, personas can be an incredibly powerful tool for designing products if done properly. However, the designers and researchers creating personas must be cautious of stereotype and classification implications.

A user persona profile typically includes an imaginary name, picture, and summary of various attitudes, behaviors, and goals for the user that it is trying to portray [4]. There is no standard template for creating user personas; therefore, they can be used to represent various characteristics of users. Ultimately, user personas visualize a broad range of qualitative and quantitative data that can later be used in the problem solving processes in various industries.

Designers manually creating personas open up a chance for self-referential designing, crafting personas for their own goals, and other biases. Even as user personas advance and the approach becomes more data centric, there are ethical concerns in regard to biasing or stereotyping users into certain personas. Data-driven personas combine empathy and analytics using computational methods. Using such algorithmic methods to turn user data into personas can lead to bias and prejudice if there’s a lack of transparency [5]. Researchers are becoming increasingly invested into data-driven personas in order to assess their true ethical implications.

Contents

History

User personas were coined by Alan Cooper, an American software designer and programmer best known for Visual Basic, user experience, and interaction design [6]. While navigating design problems of his own, Coopert realized there was a gap between software developers and the actual users that would be using the products. Up until this point, software had been constructed in a way that focused on the way to code and not the way to design in order to meet user needs. Copper began to use a role-playing technique while navigating his own design problems, thus ideating the first types of user personas.

By focusing on his user design methodologies, Cooper started articulating his own design principles that would later become the foundation of user personas. He started articulating his new insight to other companies and the common sentiment was that digital products should be designed with the users’ needs as the priority. User personas gained popularity in the online business and technology world after this breakthrough described in Cooper’s 1999 book The Inmates are Running the Asylum [7]. In the book, Cooper provided an overview of persona qualities, use cases, and other recommendations for creating personas. Today, Cooper’s user centered design strategies are accepted widely across the human-computer interaction industry. As user personas have become more widespread, they have developed and different strategies have come to existence.

Creation Process

Original user personas were just initial rough sketches from Alan Cooper; however, they have now evolved to incorporate data and become more detailed characters [8]. Now, they are typically a one-page design tool that visualizes user information. Before creating user personas, designers tend to conduct quantitative and qualitative research in order to gather enough data to adequately represent the users they are designing for. This could look like distributing surveys, conducting user interviews, having usability testing, A/B testing, or more. Relevant data is then organized into personal types based on common desires, characteristics, and pain points. From there, teams can begin turning their user information into user personas.

User experience designers and researchers will vary the exact process for constructing personas, but personas tend to contain the same componenents [9]. In the CareerFoundry UX Bootcamp course, industry professionals encourage designers to include four key pieces of information when it comes to crafting their user personas [10].

Name, Image, & Quote

User personas usually include a header area that contains a fictional name, stock image or graphic, and quote that summarizes the most important need for the user. Providing a name and image helps personify the persona and makes it memorable for the team to work on. The name and image can be entirely made up to the designer's discretion, but the quote is derived from user research. It is recommended that names be gender neutral to avoid any stereotyping [11].

Demographics

In addition to a quote, demographic information is factual and drawn directly from research. It can include a user’s personal background like their age, gender, education, ethnicity, or family status. Demographic profiles can also include professional aspects of users such as their income level, occupation, and other professional experience. Demographics encompassed in personas should be included if they can explicitly help make a design decision later on [12].

End goals

Since user personas were created as a way to communicate user needs, including end goals in a persona ensures that products are designed in a way that help users fulfill their needs. These can be explicitly stated by users, or it can be a synthesized goal from multiple perspectives.

Scenario

Lastly, user personas tend to include a short, descriptive narrative that details how a user’s interaction with the product in a certain way would help fulfill their goals. This helps those using personas imagine the persona character in a real world scenario.

Data-Driven Personas

User personas became a common design method that was relatively easy for designers to create, but design teams creating personas manually might not be robust and accurate. There has been a recent shift towards more data-driven personas that focus on real customer data and not just a subset of user research [13]. Data-driven personas are user personas that are created algorithmically from observed user behavior and demographic data. In “Data-driven persona development,” Jennifer McGinn and Nalini Kotamraju suggest that researchers should create and validate personas through a statistical analysis of data. These data-driven personas take user data and quantitative methods and create personas in an inexpensive and quick manner. Additionally, it removes the time that designers spend creating personas themselves [14].

When it comes to creating personas in a data centric way, teams typically take data from surveys or user demographics and use algorithms to create segments that can be turned into personas. Before getting started, designers discuss with a team of stakeholders which user attributes are most important to include in data collection and analysis [15]. From there, factor analysis is used to group different users together. For example, a questionnaire could ask questions regarding which tasks someone does at work. From there, companies analyze different answers and yield typical occupations and tasks users might have.

Benefits of creating personas

User personas have been beneficial to the design process for various reasons according to Pruitt and Adlin [16]. Personas are often used as a communication tool for engineers, designers, and product managers to work with user data and use it to inform their design decisions. As companies adopt their own method of incorporating user personas into their process, personas make different user types easily memorable.

Spotify, a company known for its established design team, spent 2 years developing 5 personas using Alan Cooper’s method and the Grounded Theory approach [17].

Spotify incorporated the five personas into their entire design workspace by creating cardboard cutouts, card games, and digital aspects like ‘Which Persona Are You?” Spotify instantly saw an advantageous impact to using the personas; having personas helped create educated hypotheses that eventually saved the design team time from doing redundant user research. Spotify saw such promising benefits after creating their personas that they plan to expand and adapt their user personas for their different international markets outside the US.

User personas are not exclusively beneficial for large companies; personas are used to assist in making design decisions at any level. At the core, user personas can help build empathy for users being designed for. Creating personas helps developers and designers gain a better understanding of the user and think about them as an actual person [18]. This allows designers to think about what an actual person might want or need from their perspective. Additionally, having an empathetic approach towards personas pushes designers to design the best product for their users since they are identifying with the personas.

Another benefit is that user personas can help make quick design decisions without relying on spending time and money on more user research. When it comes to prioritizing features, designers will consider the goals of the business to a certain extent, but they can also influence their decisions based on how well the feature would address the wants and needs of their certain user personas they have created.

Ethical Concerns

User personas are seen as a common design process component in the human computer interaction industry that can reap several benefits for design teams; however, there are some criticisms for both manually creating personas as well as data-driven personas.

Elastic User

When designers are creating user personas by hand and not relying on data centric algorithms, this could introduce personal bias from those creating them. In About Face 2.0, Alan Cooper criticized personas and brought up the idea of an Elastic User [19]. An elastic user is an ill-defined persona that fluctuates depending on the needs of the developer, designer, or other stakeholder creating it. An example of this, as described by Cooper, could occur when a development team overestimates a user’s technology literacy and then fleshes out features that would be relevant to the development team. With this, real users may not have their needs appropriately met based on their own goals and abilities.

Additionally, elastic users are inherently generic; thus, different stakeholders or developers may define what the user persona is according to their own motivations and desires [20]. If a user persona is created too generic, then the meaning behind it could fluctuate and the real user needs might not be truly reflected.

Self-Referential Design & Bias

For the most part, personas contain qualitative data about users such as gender, marital status, social class, and technology proficiency. Although UX professionals draw directly from research for different qualitative aspects of a user persona, they might subconsciously create user personas with their own identities or mental models in mind, thus creating biased personas [21]. Designers may select names, ages, genders, or other qualities that are either similar to them or similar to those in their communities around them. As a result, if there is not a diverse set of voices involved in creating personas then they can be unrepresentative of the real user population.

Self referential design was another criticism that Alan Cooper had called out, and he described it as “designing for oneself rather than for the audience.” [22] Designers and developers who fail to extrapolate from their own experiences and design for themselves as opposed to users risk losing customers and creating a negative user experience. Similarly, to designing for oneself, designers can also design with a specific friend, family member, co-worker, or other closely related person in mind. To mitigate this, designers can consider avoiding names of people that the team knows and would subconsciously think about as the persona.

- ↑ Pruitt, John, and Jonathan Grudin. “Personas.” Proceedings of the 2003 Conference on Designing for User Experiences - DUX '03, 6 June 2003, https://doi.org/10.1145/997078.997089.

- ↑ An, J., et al. “Imaginary People Representing Real Numbers.” ACM Transactions on the Web, vol. 12, no. 4, 2018, pp. 1–26., https://doi.org/10.1145/3265986.

- ↑ Salminen, Joni, et al. “From 2,772 Segments to Five Personas: Summarizing a Diverse Online Audience by Generating Culturally Adapted Personas.” First Monday, 2018, https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v23i6.8415.

- ↑ Nielsen, Lene, et al. “A Template for Design Personas.” International Journal of Sociotechnology and Knowledge Development, vol. 7, no. 1, 2015, pp. 45–61., https://doi.org/10.4018/ijskd.2015010104.

- ↑ Salminen, Joni O, et al. “Are Data-Driven Personas Considered Harmful?” Persona Studies, vol. 7, no. 1, 2021, pp. 48–63., https://doi.org/10.21153/psj2021vol7no1art1236.

- ↑ Cooper, Alan. The Inmates Are Running the Asylum: Why Tech Products Drive Us Crazy and How to Restore the Sanity. Sams, 1999.

- ↑ Cooper, Alan. The Inmates Are Running the Asylum: Why Tech Products Drive Us Crazy and How to Restore the Sanity. Sams, 1999.

- ↑ Cooper, Alan, and Robert Reimann. About Face 2.0: The Essentials of Interaction Design. Wiley, 2003.

- ↑ Pruitt, John, and Jonathan Grudin. “Personas.” Proceedings of the 2003 Conference on Designing for User Experiences - DUX '03, 2003, https://doi.org/10.1145/997078.997089.

- ↑ Veal, Raven. “How to Define a User Persona [2022 Guide].” CareerFoundry, 23 Nov. 2021, https://careerfoundry.com/en/blog/ux-design/how-to-define-a-user-persona/.

- ↑ Marriott, Jessica. “Beware of Persona Bias.” Bentley University, 2019, https://www.bentley.edu/centers/user-experience-center/beware-persona-bias.

- ↑ Faller, Patrick. “What Are User Personas and Why Are They Important?” Ideas, 17 Dec. 2019, https://xd.adobe.com/ideas/process/user-research/putting-personas-to-work-in-ux-design/.

- ↑ McGinn, Jennifer (Jen), and Nalini Kotamraju. “Data-Driven Persona Development.” Proceeding of the Twenty-Sixth Annual CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - CHI '08, 6 Apr. 2008, https://doi.org/10.1145/1357054.1357292.

- ↑ Salminen, Joni, et al. “The Future of Data-Driven Personas: A Marriage of Online Analytics Numbers and Human Attributes.” Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems, 2019, https://doi.org/10.5220/0007744706080615.

- ↑ McGinn, Jennifer (Jen), and Nalini Kotamraju. “Data-Driven Persona Development.” Proceeding of the Twenty-Sixth Annual CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - CHI '08, 2008, https://doi.org/10.1145/1357054.1357292.

- ↑ Adlin, Tamara. The Persona Lifecycle: Keeping People in Mind throughout Product Design. Morgan Kaufmann Publishers Inc, 2006.

- ↑ Karol, Sohit, et al. “The Story of Spotify Personas.” Spotify Design, Mar. 2019, https://spotify.design/article/the-story-of-spotify-personas.

- ↑ Faller, Patrick. “What Are User Personas and Why Are They Important?: Adobe XD Ideas.” Ideas, 17 Dec. 2019, https://xd.adobe.com/ideas/process/user-research/putting-personas-to-work-in-ux-design/#:~:text=User%20personas%20are%20archetypical%20users,see%20in%20the%20example%20below.

- ↑ Cooper, Alan, and Robert Reimann. About Face 2.0: The Essentials of Interaction Design. Wiley, 2003.

- ↑ Babich, Nick. “Putting Personas to Work in UX Design: What They Are and Why They're Important.” Adobe, 29 Sept. 2017, https://blog.adobe.com/en/publish/2017/09/29/putting-personas-to-work-in-ux-design-what-they-are-and-why-theyre-important#gs.on11tg.

- ↑ Marriott, Jessica. “Beware of Persona Bias.” Bentley University, 2019, https://www.bentley.edu/centers/user-experience-center/beware-persona-bias.

- ↑ Cooper, Alan, and Robert Reimann. About Face 2.0: The Essentials of Interaction Design. Wiley, 2003.