User personas

A user persona (also customer persona, user type, archetype) in human-computer design is a fabricated profile used to represent realistic aspects of the user or customer segment who are intended to use certain applications, websites, or other digital products [1]. Personas embody important aspects and help personify user data [2]. It is a type of research method that takes a diverse and complex audience and condenses all of their data into a few archetypes that sum up their needs and desires [3]. As a popular method of representing hypothesized users, personas can be an incredibly powerful tool for designing products if done properly. However, the designers and researchers creating personas must be cautious of stereotype and classification implications.

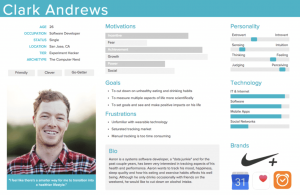

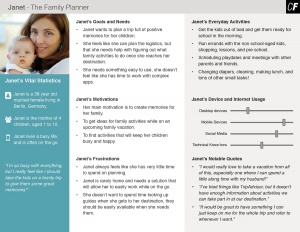

A user persona profile typically includes an imaginary name, picture, and summary of various attitudes, behaviors, and goals for the user that it is trying to portray [4]. There is no standard template for creating user personas; therefore, they can be used to represent various characteristics of users. Ultimately, user personas visualize a broad range of qualitative and quantitative data that can later be used in the problem solving processes in various industries.

Designers manually creating personas open up a chance for self-referential designing, crafting personas for their own goals, and other biases. Even as user personas advance and the approach becomes more data centric, there are ethical concerns in regard to biasing or stereotyping users into certain personas. Data-driven personas combine empathy and analytics using computational methods. Using such algorithmic methods to turn user data into personas can lead to bias and prejudice if there’s a lack of transparency [5]. Researchers are becoming increasingly invested into data-driven personas in order to assess their true ethical implications.

Contents

History

User personas were coined by Alan Cooper, an American software designer and programmer best known for Visual Basic, user experience, and interaction design [6]. While navigating design problems of his own, Cooper realized there was a gap between the software developers who were creating the products and the actual users that would be using them. Up until this point, software had been constructed in a way that focused on the way to code and not the way to design in order to meet user needs. Copper began to use a role-playing technique while navigating his own design problems, thus ideating the first types of user personas.

By focusing on his user design methodologies, Cooper started articulating his own design principles that would later become the foundation of user personas. He started articulating his new insight to other companies and the common sentiment was that digital products should be designed with the users’ needs as the priority. User personas gained popularity in the online business and technology world after this breakthrough described in Cooper’s 1999 book The Inmates are Running the Asylum [7]. In the book, Cooper provided an overview of persona qualities, use cases, and other recommendations for creating personas. Today, Cooper’s user centered design strategies are accepted widely across the human-computer interaction industry. As user personas have become more widespread, they have developed and different strategies have come to existence.

Creation Process

Original user personas were just initial rough sketches from Alan Cooper; however, they have now evolved to incorporate data and become more detailed characters [8]. Now, they are typically a one-page design tool that visualizes user information. Before creating user personas, designers tend to conduct quantitative and qualitative research in order to gather enough data to adequately represent the users they are designing for. This could look like distributing surveys, conducting user interviews, having usability testing, A/B testing, or more. Relevant data is then organized into personal types based on common desires, characteristics, and pain points. From there, teams can begin turning their user information into user personas.

If design teams are either limited with time, budget, or other resources necessary for conducting user research, companies can use stakeholder insights and competitor analysis [9]. When doing this, personas should still attempt to represent the actual users that would use the product and not fictional characters. For example, making a persona named "Hannah Montana" would make people think of the fictional role and not a real user who could be using the product.

User experience designers and researchers will vary the exact process for constructing personas, but personas tend to contain the same componenents [10]. In the CareerFoundry UX Bootcamp course, industry professionals encourage designers to include four key pieces of information when it comes to crafting their user personas [11].

Name, Image, & Quote

User personas usually include a header area that contains a fictional name, stock image or graphic, and quote that summarizes the most important need for the user. Providing a name and image helps personify the persona and makes it memorable for the team to work on. The name and image can be entirely made up to the designer's discretion, but the quote is derived from user research. It is recommended that names be gender neutral to avoid any stereotyping [12].

Demographics

In addition to a quote, demographic information is factual and drawn directly from research. It can include a user’s personal background like their age, gender, education, ethnicity, or family status. Demographic profiles can also include professional aspects of users such as their income level, occupation, and other professional experience. When choosing what to include, demographics highlighted in personas should be included if they can explicitly help make a design decision later on. An example demographic profile might be: Harvey, 52 years old, divorced father of two, has a Master’s degree in mathematics [13].

End goals

Since user personas were created as a way to communicate user needs, including end goals in a persona ensures that products are designed in a way that help users fulfill their needs. These can be explicitly stated by users, or it can be a synthesized goal from multiple perspectives.

Scenario

Lastly, user personas tend to include a short, descriptive narrative story that details how a user’s interaction with the product in a certain way would help fulfill their goals. This helps those using personas imagine the persona character in a real world scenario. This can also help the design team develop certain tasks for usability testing if they consider how exactly the persona might be behaving [14].

Data-Driven Personas

User personas became a common design method that was relatively easy for designers to create, but design teams creating personas manually might not be robust and accurate. There has been a recent shift towards more data-driven personas that focus on real customer data and not just a subset of user research [15]. Data-driven personas are user personas that are created algorithmically from observed user behavior and demographic data. In “Data-driven persona development,” Jennifer McGinn and Nalini Kotamraju suggest that researchers should create and validate personas through a statistical analysis of data. These data-driven personas take user data and quantitative methods and create personas in an inexpensive and quick manner. Additionally, it removes the time that designers spend creating personas themselves [16].

There have been a number of online analytics platforms and tools that organizations can use to help segment their users and understand them better. Adobe Analytics, IBM Analytics, Facebook Insights, and Google Analytics are all services that can be used to help create personas from large quantities of user data [17].

When it comes to creating personas in a data centric way, teams typically take data from surveys or user demographics and use algorithms to create segments that can be turned into personas. Before getting started, designers discuss with a team of stakeholders which user attributes are most important to include in data collection and analysis [18]. From there, factor analysis is used to group different users together. For example, a questionnaire could ask questions regarding which tasks someone does at work. From there, companies analyze different answers and yield typical occupations and tasks users might have.

A real world example of a company using data-driven personas is Salesforce. Since Salesforce has a wide range of users in different industries and regions, Salesforce uses data-driven personas to better understand users through large-scale surveys and clustering and factor analysis [19]. To start, Salesforce collects information about who users are, their job responsibilities, softwares utilized, and pain points. From there, they use analysis to craft personas and group them into various mutually-exclusive groups. The data-driven personas are then used to communicate with other stakeholders and to develop features that their customers will like.

Benefits of creating personas

User personas have been beneficial to the design process for various reasons according to Pruitt and Adlin [20]. Personas are often used as a communication tool for engineers, designers, and product managers to work with user data and use it to inform their design decisions. As companies adopt their own method of incorporating user personas into their process, personas make different user types easily memorable.

Spotify, a company known for its established design team, spent 2 years developing 5 personas using Alan Cooper’s method and the Grounded Theory approach [21].

Spotify incorporated the five personas into their entire design workspace by creating cardboard cutouts, card games, and digital aspects like ‘Which Persona Are You?” Spotify instantly saw an advantageous impact to using the personas; having personas helped create educated hypotheses that eventually saved the design team time from doing redundant user research. Spotify saw such promising benefits after creating their personas that they plan to expand and adapt their user personas for their different international markets outside the US.

User personas are not exclusively beneficial for large companies; personas are used to assist in making design decisions at any level. At the core, user personas can help build empathy for users being designed for. Creating personas helps developers and designers gain a better understanding of the user and think about them as an actual person [22]. This allows designers to think about what an actual person might want or need from their perspective. Additionally, having an empathetic approach towards personas pushes designers to design the best product for their users since they are identifying with the personas.

Another benefit is that user personas can help make quick design decisions without relying on spending time and money on more user research. When it comes to prioritizing features, designers will consider the goals of the business to a certain extent, but they can also influence their decisions based on how well the feature would address the wants and needs of their certain user personas they have created.

Ethical Concerns

User personas are seen as a common design process component in the human computer interaction industry that can reap several benefits for design teams; however, there are some criticisms for both manually creating personas as well as data-driven personas.

Elastic User

When designers are creating user personas by hand and not relying on data centric algorithms, this could introduce personal bias from those creating them. In About Face 2.0, Alan Cooper criticized personas and brought up the idea of an Elastic User [23]. An elastic user is an ill-defined persona that fluctuates depending on the needs of the developer, designer, or other stakeholder creating it. An example of this, as described by Cooper, could occur when a development team overestimates a user’s technology literacy and then fleshes out features that would be relevant to the development team. With this, real users may not have their needs appropriately met based on their own goals and abilities.

Additionally, elastic users are inherently generic; thus, different stakeholders or developers may define what the user persona is according to their own motivations and desires [24]. If a user persona is created too generic, then the meaning behind it could fluctuate and the real user needs might not be truly reflected.

Self-Referential Design & Bias

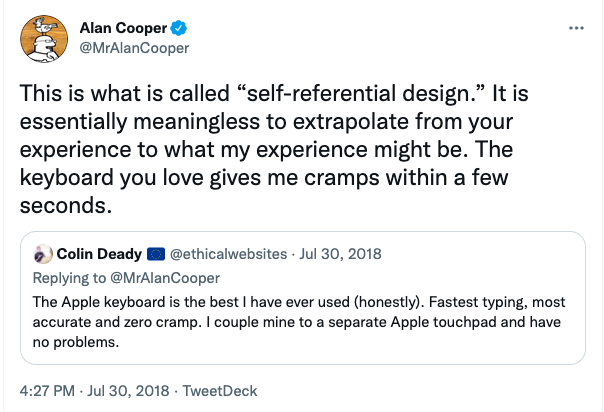

For the most part, personas contain qualitative data about users such as gender, marital status, social class, and technology proficiency. Although UX professionals draw directly from research for different qualitative aspects of a user persona, they might subconsciously create user personas with their own identities or mental models in mind, thus creating biased personas [25]. Designers may select names, ages, genders, or other qualities that are either similar to them or similar to those in their communities around them. As a result, if there is not a diverse set of voices involved in creating personas then they can be unrepresentative of the real user population.

Self referential design was another criticism that Alan Cooper had called out, and he described it as “designing for oneself rather than for the audience.” [26] Designers and developers who fail to extrapolate from their own experiences and design for themselves as opposed to users risk losing customers and creating a negative user experience. Similarly, to designing for oneself, designers can also design with a specific friend, family member, co-worker, or other closely related person in mind. To mitigate this, designers can consider avoiding names of people that the team knows and would subconsciously think about as the persona.

Another instance where designers may incorporate their self biases is in the creation of Proto Personas [27]. Proto personas are simple personas created from no new research that are meant to be used for quick brainstorming and initial assumptions. Instead, they rely on the team’s existing preconceptions and knowledge based on who their users are and what their needs entail. Since these prototypes are not explicitly driven by research, they are not as accurate. Designers and stakeholders may rely on their own experiences and wants when designing what they think users will want.

Algorithmic Bias

Scholars have been critical of data-driven personas specifically as they rely on algorithmic decision-making systems that tend to overlook various user characteristics. Ethical concerns that have risen over data-driven personas include aspects like fairness, privacy, transparency, and trust [28]. Ethics surrounding algorithmic design has been explored in the past, but there is limited research on data-driven personas specifically. Machine learning and automation have a consensus in the computer science and human computer interaction field as having ethical issues, and data-driven personas have used machine learning and automation [29].

The goal of quantifying personas is to create more accurate user personas from real data, but ethical ramifications are often overlooked when personas are created. One concern when dealing with large sums of data in persona creation is stereotyping personas into certain categories. Race, for example, is a characteristic that personas default to having. Racial stereotypes can have an impact when creating personas from data and data-driven personas can become politicized [30]. Scholars are currently researching ways to satisfy fairness and non-discrimination while making data-driven personas from group demographics.

Data Collection

In order to create user personas from quantitative information, data must be collected about real users. Data is often collected automatically through application programming interfaces (APIs) and social media platforms [31]. With copious amounts of data being collected, this opens up questions surrounding data privacy, consent, and transparency. Data privacy and consent in regards to user personas has been discussed because although users may post social media content online publicly, they are not explicitly consenting to having their profile data analyzed and created into potential user personas [32]. European researchers have looked into how users’ privacy may actually be in danger, and they argued that datasets are typically aggregated and their individual identities are diminished [33].

Misusing Personas

Personas can be useful tools for the design teams who create them, but not all personas are successfully used. According to the Nielsen Norman Group, the World's Leaders in Research-Based User Experience, personas can fail if designers succumb to various pitfalls [34]. One pitfall is that personas might not be used as intended upon creation. When there is a failure to communicate and educate other team members about the company’s personas, not everyone will comprehend why personas are being used or how to use them for decision making. Nielsen Norman Group said introducing personas to teams by teaching them how to interpret them and encouraging them to make personas something that can be organically referenced throughout work could help make persona use appropriate.

Since personas contain demographic information about users, those not familiar with the personas may impose their own beliefs and assumptions onto different users. Different people may misuse and interpret the personas in different ways than originally intended. By looking at different traits a user persona possesses such as someone’s age, sex, race, etc., team members might have subconscious ideas of how a person would act based on their sex or race.

Classification of Personas

When it comes to classifying users into different personas, not everyone will always fit into a mutually exclusive category perfectly. With personas, designers take user data and then classify users either manually or with factor analysis. Classification systems in general are a way humans sort various things into different piles and implicit labels [35]. Classification is also a way to make decisions based on what matters in the world, and the people creating such classifications are the ones that have a say. Depending on the stakeholders involved in deciding how user data should be collected and classified, personas could change widely. Additionally, not having a wide range of voices in the room when it comes to deciding what attributes should be considered results in an undiversified set of user personas.

References

- ↑ Pruitt, John, and Jonathan Grudin. “Personas.” Proceedings of the 2003 Conference on Designing for User Experiences - DUX '03, 6 June 2003, https://doi.org/10.1145/997078.997089.

- ↑ An, J., et al. “Imaginary People Representing Real Numbers.” ACM Transactions on the Web, vol. 12, no. 4, 2018, pp. 1–26., https://doi.org/10.1145/3265986.

- ↑ Salminen, Joni, et al. “From 2,772 Segments to Five Personas: Summarizing a Diverse Online Audience by Generating Culturally Adapted Personas.” First Monday, 2018, https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v23i6.8415.

- ↑ Nielsen, Lene, et al. “A Template for Design Personas.” International Journal of Sociotechnology and Knowledge Development, vol. 7, no. 1, 2015, pp. 45–61., https://doi.org/10.4018/ijskd.2015010104.

- ↑ Salminen, Joni O, et al. “Are Data-Driven Personas Considered Harmful?” Persona Studies, vol. 7, no. 1, 2021, pp. 48–63., https://doi.org/10.21153/psj2021vol7no1art1236.

- ↑ Cooper, Alan. The Inmates Are Running the Asylum: Why Tech Products Drive Us Crazy and How to Restore the Sanity. Sams, 1999.

- ↑ Cooper, Alan. The Inmates Are Running the Asylum: Why Tech Products Drive Us Crazy and How to Restore the Sanity. Sams, 1999.

- ↑ Cooper, Alan, and Robert Reimann. About Face 2.0: The Essentials of Interaction Design. Wiley, 2003.

- ↑ Talebook. “How to Create Personas, a Step by Step Guide.” Medium, UX Planet, 1 Oct. 2019, https://uxplanet.org/how-to-create-personas-step-by-step-guide-303d7b0d81b4.

- ↑ Pruitt, John, and Jonathan Grudin. “Personas.” Proceedings of the 2003 Conference on Designing for User Experiences - DUX '03, 2003, https://doi.org/10.1145/997078.997089.

- ↑ Veal, Raven. “How to Define a User Persona [2022 Guide].” CareerFoundry, 23 Nov. 2021, https://careerfoundry.com/en/blog/ux-design/how-to-define-a-user-persona/.

- ↑ Marriott, Jessica. “Beware of Persona Bias.” Bentley University, 2019, https://www.bentley.edu/centers/user-experience-center/beware-persona-bias.

- ↑ Faller, Patrick. “What Are User Personas and Why Are They Important?” Ideas, 17 Dec. 2019, https://xd.adobe.com/ideas/process/user-research/putting-personas-to-work-in-ux-design/.

- ↑ Lyst, Jim, and Michael Frontz. “Personas and Scenarios.” Personas and Scenarios - CxD Principles & Practices, 2019, https://docs.idew.org/principles-and-practices/practices/design-practices/personas.

- ↑ McGinn, Jennifer (Jen), and Nalini Kotamraju. “Data-Driven Persona Development.” Proceeding of the Twenty-Sixth Annual CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - CHI '08, 6 Apr. 2008, https://doi.org/10.1145/1357054.1357292.

- ↑ Salminen, Joni, et al. “The Future of Data-Driven Personas: A Marriage of Online Analytics Numbers and Human Attributes.” Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems, 2019, https://doi.org/10.5220/0007744706080615.

- ↑ Jansen, Bernard J., et al. “Data-Driven Personas for Enhanced User Understanding: Combining Empathy with Rationality for Better Insights to Analytics.” Data and Information Management, vol. 4, no. 1, 2020, pp. 1–17., https://doi.org/10.2478/dim-2020-0005.

- ↑ McGinn, Jennifer (Jen), and Nalini Kotamraju. “Data-Driven Persona Development.” Proceeding of the Twenty-Sixth Annual CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - CHI '08, 2008, https://doi.org/10.1145/1357054.1357292.

- ↑ Vincent-Hill, Alyssa. “Data-Driven Personas at Salesforce.” Medium, Salesforce Design, 1 Mar. 2017, https://medium.com/salesforce-ux/data-driven-personas-at-salesforce-cdd0dd321281.

- ↑ Adlin, Tamara. The Persona Lifecycle: Keeping People in Mind throughout Product Design. Morgan Kaufmann Publishers Inc, 2006.

- ↑ Karol, Sohit, et al. “The Story of Spotify Personas.” Spotify Design, Mar. 2019, https://spotify.design/article/the-story-of-spotify-personas.

- ↑ Faller, Patrick. “What Are User Personas and Why Are They Important?: Adobe XD Ideas.” Ideas, 17 Dec. 2019, https://xd.adobe.com/ideas/process/user-research/putting-personas-to-work-in-ux-design/#:~:text=User%20personas%20are%20archetypical%20users,see%20in%20the%20example%20below.

- ↑ Cooper, Alan, and Robert Reimann. About Face 2.0: The Essentials of Interaction Design. Wiley, 2003.

- ↑ Babich, Nick. “Putting Personas to Work in UX Design: What They Are and Why They're Important.” Adobe, 29 Sept. 2017, https://blog.adobe.com/en/publish/2017/09/29/putting-personas-to-work-in-ux-design-what-they-are-and-why-theyre-important#gs.on11tg.

- ↑ Marriott, Jessica. “Beware of Persona Bias.” Bentley University, 2019, https://www.bentley.edu/centers/user-experience-center/beware-persona-bias.

- ↑ Cooper, Alan, and Robert Reimann. About Face 2.0: The Essentials of Interaction Design. Wiley, 2003.

- ↑ Laubheimer, Paige. “3 Persona Types: Lightweight, Qualitative, and Statistical.” Nielsen Norman Group, 21 June 2020, https://www.nngroup.com/articles/persona-types/.

- ↑ Green, Ben, and Yiling Chen. “The Principles and Limits of Algorithm-in-the-Loop Decision Making.” Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, vol. 3, no. CSCW, 2019, pp. 1–24., https://doi.org/10.1145/3359152.

- ↑ An, J., et al. “Imaginary People Representing Real Numbers.” ACM Transactions on the Web, vol. 12, no. 4, 2018, pp. 1–26., https://doi.org/10.1145/3265986.

- ↑ Salminen, Joni, et al. “‘Is More Better?’” Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 21 Apr. 2018, https://doi.org/10.1145/3173574.3173891.

- ↑ Jung, Soon-Gyo et al. “Automatically Conceptualizing Social Media Analytics Data via Personas.” ICWSM (2018).

- ↑ Fiesler, Casey, and Nicholas Proferes. “‘Participant’ Perceptions of Twitter Research Ethics.” Social Media + Society, Jan. 2018, doi:10.1177/2056305118763366.

- ↑ Wöckl, Bernhard, et al. “Basic Senior Personas: a Representative Design Tool Covering the Spectrum of European Older Adults.” Proceedings of the 14th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility - ASSETS '12, 22 Oct. 2012, https://doi.org/10.1145/2384916.2384922.

- ↑ Salazar, Kim. “Why Personas Fail.” Nielsen Norman Group, 28 Jan. 2018, https://www.nngroup.com/articles/why-personas-fail/.

- ↑ Bowker, Geoffrey C., and Susan Leigh Star. Sorting Things out: Classification and Its Consequences. MIT Press, 2008.