Stan Twitter

Stan Twitter refers to communities of users on Twitter (and other social media platforms) that share posts, comments, and memes surrounding pop culture, celebrities, movies, music, social media, and even sports. The communities are known for their shared terminology and use of language on the internet. They help build a sense of community for people who are interested in the same things. Fandoms have been around for a long time, and Stan Twitter allows people to keep up with their favorite pop culture moments right at their fingertips. However, in the past few years, they have been associated for their constant involvement in online harassment, cyber-bullying, and doxing. Though these communities were originally created for fans to support their favorite artists and pieces of media, Stan Twitter has grown to become a divisive online community that holds a large presence in almost every corner of the internet, not just Twitter. [1].

Contents

Origin

As a result of the information age, people now have access to almost anything and everything. Especially in an age of oversharing, platforms like Twitter allow fans to constantly know what their favorite artists are up to and even directly interact with them. The term “Stan Twitter” is a combination of the two words “fan” and “stalker”. It was first coined in an Eminem song called “Stan” in the year 2000. The song was about an obsessive Eminem fan and how his obsessive behavior ruined his relationships with people. Though the original meaning of the word was for people who are obsessive like the guy in the song, it has grown to become a “badge of honor” for fans who are willing to go above and beyond to show their commitment and love for their favorite artists. [2] The presence of stan culture isn’t just on Twitter, however. Stan culture is prevalent in every social media platform, including Instagram and TikTok. Even though the term has stayed relevant twenty years later, the culture of the fandoms have developed into a phenomenon that has implications beyond the screen and into the real lives of people. [3]

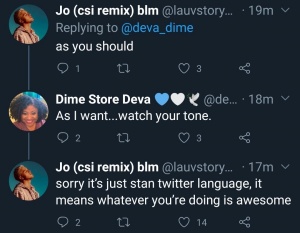

Stan Twitter uses a shared terminology and the language they use on the internet can oftentimes confuse users who are not a part of the community. Stans “often use strange jargon like ‘wig’ or ‘tea’”.[4] In addition, they refer to those outside of Stan Twitter “locals.” While the idea of stan culture may seem odd to people who are not familiar with it all, it is becoming more socially acceptable within the past few years following the rise of its popularity. Because of this, many stans have built up the courage to reveal themselves and not just hide behind a screen. Ultimately, stan culture can act as a support group for people with shared hobbies and interests. As a result, people within the communities don’t just talk about their favorite celebrities and pop culture media. They often times help each other and update one another on what’s going on in their lives, using the stan community as an online support group. These online friends can provide the support for people when those people don’t have the support they need in real life.

Fandom Names

One of the more popular fandoms on Stan Twitter are the fans of musical artists. The most prominent are the “stans” of Ariana Grande, Nicki Minaj, Cardi B, K-pop stans, and many more. Stans usually have a name for themselves for each artist. For example, Lady Gaga stans are called Little Monsters. Ariana Grande stans are called Arianators. Nicki Minaj stans are Barbz, BTS stans are called Army, Taylor Swift stans are Swifties, and Beyonce stans identify with the Beyhive. [5]

Stan Twitter and Politics

When France entered lockdown during the early stages of the Coronavirus, Lorian De Sousa (20) created an account on Twitter called “Out of context Hannah Montana” because he had nothing better to do with his free time. Through that account, he would post random scenes from the Disney Channel show “Hannah Montana.” The account garnered a lot of attention in a short amount of time and now has more than 65 thousand followers on Twitter. Unexpectedly, it became a center for activism and political engagement, something that De Sousa would have never suspected when he first made the account. In 2020, as the pandemic ravaged the United States, it forced more and more people inside their homes and into digital spaces as opposed to real-life spaces. At the same time, as numerous political and social issues dominated the news, stan accounts on social media played a big part in influencing issues and outcomes surrounding social movements such as Black Lives Matter. In addition, stan accounts played a massive role in impacting the 2020 U.S. presidential election. [6]

Perhaps the event that permanently changed the culture of the stan communities was the death of George Floyd in May of 2020. Stan Twitter played a big part in the rallying and support for the Black Lives Matter movement and the protests against anti-Black discrimination. Even people outside of the United States joined in on these movements, including De Sousa himself.

De Sousa took advantage of his big fan base and used his stan account as a voice for social change. He would make posts that are of a “click-bait” nature, containing content that would for sure make people click on his tweet. An example of this would be a post where he would tweet out “LEAKED VIDEOS OF MILEY AND DYLAN SMOKING WEED ON SET: A THREAD.” This type of language would force users to click on the thread, only for them to be redirected to a thread of resources supporting a certain social justice issue, such as a change.org petition asking for justice for George Floyd. [7]

Though it may seem that these stan communities have joined forces to fight against social inequality, the ways in which they would stand up for these issues varied greatly. For example, K-pop stans, fans of Korean pop music, “helmed the support by trolling those who stood in opposition to the movement.” [8] In 2022, they “hijacked” racist hashtags and spaces with very random content that was completely unrelated to what the spaces were intended for. For example, they flooded the hashtags #whilelivesmatter and #MillionMAGAMarch with nonsense posts of images and videos. Because everything can be done with just the fingertips in a matter of just seconds, “mobilizing on social media becomes super easy for fans.” In an age where information is everywhere, words spread like wildfire. It’s evident through how quickly fans are able to come together and join in on issues that matter to them, even though they all live in different parts of the world. By taking collective action in just a matter of seconds, they become hyper-aware of how much digital power they have and the presence that they hold in online communities.

During the 2020 presidential campaign season, people on Stan Twitter pulled a prank on presidential candidate Donald Trump. In Tulsa, Oklahoma, Donald Trump prepares for one of his rallies. However, using online tactics, K-pop stans and users on TikTok collectively agreed to pull a prank at this rally. They purposely inflated the number of tickets registered for the campaign rally, even though they knew that they were not going to attend. The rally resulted in an underwhelming attendance and ultimately negatively affected Trump’s campaign strategies. As the election season progressed, stan accounts across Twitter used the platform to advocate for their favorite candidates. In many instances, “the political leaning of a stan account will take its cues from the values and public stances of the star the account is stanning.” Stans in 2020 have used their platform for good and they have received praise for their role in helping push forward social issues that they care deeply about. [9]

Cultural Appropriation

Though the stan communities have earned praise for their persistent fight against social injustice, the culture itself has been accused of toxic and problematic online behaviors, which include racism, bullying, and the appropriation of Black culture. Stans are often criticized for going a bit too far and acting too bold in online communities. They are often accused of appropriating Black culture, such as using African American Vernacular English (AAVE) in online platforms when they don’t identify as African American. This then leads to the debate of what exactly is categorized as AAVE and the questions of who can use it, where can they use it, and in what contexts they should use it without mocking it. “The language gets appropriated, and often there’s no sort of recognition of where it comes from. It becomes gimmicky. It can almost come off as a caricature of Black folk." [10]

Black culture heavily influences pop culture, so much so that “people unfamiliar with aspects of Black culture have reimagined Black culture to be the gateway to popularity.” AAVE is described to be an official language spoken daily by 80-90% of African Americans. However, many people label AAVE as “improper English” or “slang” because AAVE often does not follow the grammatical rules that people grew up with in school. Some examples of AAVE include the words “period”, “sis”, and “chile.” Shermarie Hyppolite, a Black American who grew up with AAVE, had to learn how to filter out that part of her language whenever she interacted with white America because her proper English was often labeled as “ghetto.” At the same time, social media has made AAVE so popular and mainstream among the non-Black community and is now deemed a trendy way of texting and speaking. Essentially, non-Black people are purposely picking it up to seem cool and hip. And this is especially true for the users on Stan Twitter, where the largest population of non-Black AAVE users reside in. [11]

The Harassment Problem

Stan Twitter and stan culture, in general, has changed a lot over the years. The people who participate in these communities have changed and with that the target audiences. The memes and ways of interacting online have changed. The language has changed. And ultimately, the culture surrounding the phenomenon has shifted into a divisive community between people who actually use the spaces to interact with their favorite celebrities and people who take advantage of Stan Twitter’s overwhelming presence online and use it to troll everyday users across all social media platforms. Following the Coronavirus lockdown in 2020, Stan Twitter is often affiliated with its many controversies of harassment and it makes users of Twitter really question the ethics of this product of the information revolution.

Sometimes, people accuse the artists themselves of playing a role in allowing fans to carry out nasty behavior on the internet. A man on the internet, who we will call John to protect his actual identity, was a victim of such harassment on the internet by Stan Twitter. He knew something was off when fans of a popular rapper “told him to choke on the chips he tweeted about.” John wrote an article on a hip-hop website stating that the popular rapper should take a year-long hiatus after producing their brand new album. Following the publication of this article, the harassment that started off as just a weird reply to a single tweet had turned into a whole campaign of hate towards John. The forms of harassment varied greatly, from receiving homophobic direct messages to comments telling him to shut his mouth. His family’s home address was even posted online for everyone to see. The harassment didn’t just stay within Twitter. On Instagram, fans of the rapper would direct one another to go on Twitter and fan the flames of the fire. This is proof that although Stan Twitter is capable of carrying out good deeds (for example, serving as a tight-knit community for fans to enjoy their favorite artists, helping give the artists the publicity that they need, and raising money for charitable causes), it is also capable of very harmful behaviors that could lead to serious consequences for both the stans and the victims. [12]

Harassment has also been an issue plaguing the stan community ever since 2016. As described by Affinity Magazine, Stan Twitter has turned into a “playground for bullies.” [13] Emma Jane, an associate professor at the University of New South Wales Sydney, explained to Insider that members of fandoms would often take media commentator’s critiques very personally, even if it’s mild criticism. For example, in July of 2020, a group of Swifties (fans of Taylor Swift) harassed and even doxxed a senior editor at a music publishing company called Pitchfork. He gave Taylor Swift’s album “Folklore” a rating of 8 out of 10, according to Motherboard publications. Doxxing is a phenomenon where people on the internet would search for and publish private information about a certain individual, usually with malicious intentions. Especially in an age where almost anyone and everyone can hide their true identities behind a screen, it’s easy for trolls online to get carried away with cyber harassment because they think they won’t have to pay any of the consequences in real life. All of this challenges the ethics of personal privacy online and raises the issue of how easy it is for random strangers to find personal information about someone. How safe is our private information really is online? [14]

In addition to digitally attacking everyday users online, fans themselves can sometimes be put in situations where they face harassment as well. This usually happens when they critique stars and hold them accountable for their actions. Stitch, a Teen Vogue columnist, tells Insider Magazine that “different aspects of our identities - and the identities of the people harassing us - inform what the harassment we get looks like and how long people feel like what they get to keep harassing us.” This breaks into intersectionality and the multiple social identities that we hold. And with each growing day, the harassment from Stan Twitter appears to be getting worse. Stich says that constant access to people online via social media has flamed the issue. [15] That brings up the question: where did all of this harassment even come from? What influenced these behaviors?

Gamergate, a trend of virtual harassment toward females in the gaming world, was one of the many events in the past decade that helped shape today’s culture of cyberbullying. It’s described that “Gamergate greatly increased public perception about the prevalence and true threat and impact of organized online harassment campaigns. It has also inspired online haters to engage in more coordinated, wide-randing, and vicious attacks.” This coordination also plays out on Stan Twitter. “Report accounts” are accounts that are created for the sole purpose of directing fans to mass-report internet users who critique the artists that fans love, usually in an effort to get rid of those accounts (ban). These actions invade the personal privacy of everyday users who want to share their opinions, and the freedom of speech of these users is also attacked. [16]

Summary (from in class workshop activity - written by peer)

Being a “super fan” is associated with problematic internet use, maladaptive daydreaming, and desire for fame. [17] Individuals reach this level of obsession due to the nature of media, specifically social media. Internet celebrities may share posts that contain intimate or emotionally intense content, making fans feel like they are a part of their lives. This creates a relationship that is not one-to-one, where the consumer spends time viewing the content, feeling like a part of the creator’s life, while the creator has no concept of who this other person is. “Parasocial interaction” describes this phenomenon. It has been present through various forms of media such as TV, movies, sports, and the internet.[18] While there are many problems associated with these obsessions, they allow the general population to form communities. These communities are prevalent in sports, as groups of people will go far to show their support for a team.[19]

Dicussion (peer review)

All sections added together, excluding the summary section come to 988 words, which confers to the requirements of the draft assignment word count. The opening describes a little summary of the origin and what stan-twitter is. The author could gain more clarity on how stan-Twitter has affected the online population by stating the pros and cons of the existence of stan-Twitter. The body paragraphs are properly broken apart into different sections and contribute to the topic at hand. A minor detail about the section headers, it would be beneficial to add more details about the text under the section headers to add clarity(specifically the politics section). The author properly cites the sources as well as references them in the body paragraphs, no further improvements are needed. The issue wasn’t apparent at first by the opening. Similar to the previous comment on the opening, adding more information regarding how stan-Twitter is affecting the population and what were the effects of stan-Twitter. This can illustrate the current situation at hand and lead to a discussion of issues and potential solutions. As there are unfinished sections in the draft still, this fix could be done after writing all body paragraphs. However, the opening gives ideas about the issues of stan-Twitter and leads to ideas regarding the discussion of its ethics. The improvement could be implemented by letting the issues of stan-Twitter lead to ethical questionings, which is then elaborated on the impact of stan-Twitter and how positively or negatively it impacts the online population.

The author doesn’t support a side on the topic and discussed the topic objectively. This is made apparent through the politics section, where the author stated the events and analyzed what stan-Twitter culture has done to the crowd or online population.- ↑ “Stan Twitter.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 22 Dec. 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stan_Twitter.

- ↑ Madden, Sidney, et al. “The 2010s: Social Media and the Birth of Stan Culture.” NPR, NPR, 17 Oct. 2019, https://www.npr.org/2019/10/07/767903704/the-2010s-social-media-and-the-birth-of-stan-culture.

- ↑ Arasa, Dale. “Have You Ever Wondered What Is Stan Twitter?” INQUIRER.net USA, 2 Apr. 2021, https://usa.inquirer.net/67142/have-you-ever-wondered-what-is-stan-twitter.

- ↑ Arasa, Dale. “Have You Ever Wondered What Is Stan Twitter?” INQUIRER.net USA, 2 Apr. 2021, https://usa.inquirer.net/67142/have-you-ever-wondered-what-is-stan-twitter.

- ↑ “The Year of the Stan: How the Internet's Super Fans Went from Pop Stars to Politics.” NBCNews.com, NBCUniversal News Group, https://www.nbcnews.com/pop-culture/pop-culture-news/year-stan-how-internet-s-super-fans-went-pop-stars-n1252115.

- ↑ “The Year of the Stan: How the Internet's Super Fans Went from Pop Stars to Politics.” NBCNews.com, NBCUniversal News Group, https://www.nbcnews.com/pop-culture/pop-culture-news/year-stan-how-internet-s-super-fans-went-pop-stars-n1252115.

- ↑ “The Year of the Stan: How the Internet's Super Fans Went from Pop Stars to Politics.” NBCNews.com, NBCUniversal News Group, https://www.nbcnews.com/pop-culture/pop-culture-news/year-stan-how-internet-s-super-fans-went-pop-stars-n1252115.

- ↑ “The Year of the Stan: How the Internet's Super Fans Went from Pop Stars to Politics.” NBCNews.com, NBCUniversal News Group, https://www.nbcnews.com/pop-culture/pop-culture-news/year-stan-how-internet-s-super-fans-went-pop-stars-n1252115.

- ↑ Leong, Dymples, et al. “K-Pop ‘Stans’ Unleashed: Hijacking Hashtags for Social Action.” Lowy Institute, 6 July 2017, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/k-pop-stans-unleashed-hijacking-hashtags-social-action.

- ↑ “The Year of the Stan: How the Internet's Super Fans Went from Pop Stars to Politics.” NBCNews.com, NBCUniversal News Group, https://www.nbcnews.com/pop-culture/pop-culture-news/year-stan-how-internet-s-super-fans-went-pop-stars-n1252115.

- ↑ Hyppolite, Shermarie. “Op-Ed: Why It's Problematic to Label AAVE as Stan Culture.” Arts + Culture, 15 Dec. 2020, https://culture.affinitymagazine.us/op-ed-why-its-problematic-to-label-aave-as-stan-culture/.

- ↑ Haasch, Palmer. “Internet Mobs of Pop-Music Fans Have Sent Waves of Harassment at Critics. Sometimes They're Fueled by the Artists Themselves.” Insider, Insider, 13 Sept. 2021, https://www.insider.com/online-mob-stan-twitter-harassment-problem-fandom-music-fan-2021-7.

- ↑ Hyppolite, Shermarie. “Op-Ed: Why It's Problematic to Label AAVE as Stan Culture.” Arts + Culture, 15 Dec. 2020, https://culture.affinitymagazine.us/op-ed-why-its-problematic-to-label-aave-as-stan-culture/.

- ↑ Haasch, Palmer. “Internet Mobs of Pop-Music Fans Have Sent Waves of Harassment at Critics. Sometimes They're Fueled by the Artists Themselves.” Insider, Insider, 13 Sept. 2021, https://www.insider.com/online-mob-stan-twitter-harassment-problem-fandom-music-fan-2021-7.

- ↑ Haasch, Palmer. “Internet Mobs of Pop-Music Fans Have Sent Waves of Harassment at Critics. Sometimes They're Fueled by the Artists Themselves.” Insider, Insider, 13 Sept. 2021, https://www.insider.com/online-mob-stan-twitter-harassment-problem-fandom-music-fan-2021-7.

- ↑ Haasch, Palmer. “Internet Mobs of Pop-Music Fans Have Sent Waves of Harassment at Critics. Sometimes They're Fueled by the Artists Themselves.” Insider, Insider, 13 Sept. 2021, https://www.insider.com/online-mob-stan-twitter-harassment-problem-fandom-music-fan-2021-7.

- ↑ Zsila, Á., McCutcheon, L. E., & Demetrovics, Z. (2018). The association of celebrity worship with problematic Internet use, maladaptive daydreaming, and desire for fame. Journal of behavioral addictions, 7(3), 654–664. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.7.2018.76

- ↑ Sussex Publishers. (n.d.). You're not really friends with that internet celebrity. Psychology Today. Retrieved January 26, 2023, from https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/your-online-secrets/201607/youre-not-really-friends-internet-celebrity

- ↑ The New Yorker. (2018, February 1). The mind of the sports superfan. The New Yorker. Retrieved January 26, 2023, from https://www.newyorker.com/sports/sporting-scene/the-mind-of-the-sports-superfan