Screen time's effect on adolescents mental health

Screen time is the aggregate time spent using a device with a digital screen, which can include computers, smartphones, tablets, TV's, and video games. There are five different categories of screen time: social, passive, interactive, educational, and other[1], and all five categories in excess show negative psychological effects. It is measured in hours per day. Mental Health is defined by the World Health Organization as a state of well-being whereby individuals recognize their true abilities, are capable of coping with the normal stresses of life, and are capable of productively and joyfully contributing to their communities[2]. The effects of screen-time on young users' mental health is an emerging area of research of the 21st century. The Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends children over 2 years of age should be restricted to 2 hours of screen time per day, yet the majority of adolescents exceed this threshold.[3] Adolescents 18-29 comprise the highest proportion of smartphone users, making up 96% of the market share of mobile phone ownership [4]. Studies show that excessive mobile screen time is significantly associated with depressive symptoms[5]. The true extent to which screen-time affects mental health is still being researched, which could inform decisions on regulation.

Contents

PHYSICAL HEALTH

Physical Activity

Screen time has been proven to have a negative linear relationship with physical activity, which is a key attribute in mental health because physical activity boosts confidence, lessens depression and anxiety, and improves sleep quality[6]. Children who watched TV for a long period of time demonstrated reduced participation in physical activities[7]. In a survey of Iranian students, those who were categorized as having high screen time usage of over 2 hours per day and a low level of physical activity of 1-2 days per week were independently associated with self-reported psychological distress by reporting symptoms of depression, anger, insomnia, worthlessness, confusion, anxiety and worry[8]. In the same study, students with high physical activity and high screen time reported less psychological distress than students with high screen time and moderate physical activity, suggesting that physical activity can improve psychological well-being irrespective of screen time[9]. High screen time also increases the chance of engaging in unhealthy behaviors that harm the physical body, such as consuming fattening food, smoking, drinking alcohol, using tobacco, and leading a life of inactivity[10]. Inactivity is linked to psychological disorders, including anxiety and depression[11]. There is an indirect link between screen-time and worser mental health due to the physical repercussions.

Overconsumption of screen time raises the chance of general physical ailments, most commonly headache and backache, as observed in adolescents who consumed more than 3 hours of daily screen time.

Diet

Screen time has an association with poorer diet. It is directly associated with adiposity, and the risk of obesity increases 13% for each additional hour of daily screen time. Each additional hour of screen time is also associated with increased consumption of high-fat and high-sugar foods and decreased consumption of fruits and vegetables. Children who consume 3 hours of daily screen time consume more snacks throughout the day. One explanation for the association between screen time and overeating is exposure to commercial advertisements that promote high-fat foods. Another explanation is passive over-consumption, varying on the level of interest in the digital entertainment. [12]

PSYCHOLOGICAL SYMPTOMS

Excess screen time in adolescents has been linked to depression and anxiety.

THEORIES OF USE

Total screen time is linearly associated with unfavorable temperament outcomes, worse socio-emotional outcomes, lower health-related quality of life, and poorer health outcomes[13]. There are more varied effects for the different categories of screen-time.

SOCIAL

Social screen time encompasses all digital social interactions, including direct messaging, social media, and FaceTime calls. Social screen time has improved the happiness of some because forming social relationships is a key indicator of someone's well-being and the digital technologies can help connect people in the information age[14]. There was a notable increase in children’s social screen time between the ages of 12 and 14 as they develop more autonomy. However, children who spent the highest amounts of time on the internet tended to be the least happy. Social screen time was linearly associated with higher reactivity, and worse socio-emotional outcomes. Social screen time does not influence hyperactivity[15].

PASSIVE

Passive screen time encompasses any digital activity in which the user is an observer of digital content. Some examples are watching TV and scrolling on social media. Of the five categories of screen usage, it has the most detrimental effects on adolescents' well-being. It is associated with worse psychological effects, including poorer pro-social behavior and lower persistence[16].

INTERACTIVE

Interactive screen time encompasses digital activity that requires the user's input, such as video games. It shows similar affects as overall screen time, however it can have positive effects on education[17].

EDUCATIONAL

Educational screen time encompasses any digital activity that involves learning. This implies it can be passive or interactive. Some examples are watching a documentary, reading a research paper, and completing an online course. Educational screen time has not been proven to produce any negative outcomes associated with overall screen time. It does produce a positive association with educational outcomes and high persistence[18].

OTHER

Other screen time captures extraneous uses of screen time that can't be categorized into passive, social, educational, or interactive categories. There is no evidence that other screen time has any association with psychological outcomes[19].

MODERATION

In the modern information age, it is inconvenient to completely eliminate screen time[20]. There are nuanced effects of screen time, such as the effects of interactive screen time that have both negative effects and positive effects on mental health, or educational screen time that aids in learning. Moderate amounts of electronic screen time are associated with higher mental well-being compared to low or high levels[21].

Goldilocks Theory

The Goldilocks theory proposes that there are thresholds of screen time in which it can be healthy and positively impact a person's wellbeing in a technologically connected world[22]. It postulates that a balancing point exists and can be achieved so it follows that screen time in moderation is not intrinsically harmful. Like Goldilocks trying extremes of soup, too much technology deprives young people of physical activity, in-person social development, and cognitive growth by replacing meaningful activities. However, too little technology may result in missing out on important information and making connections in the digital medium.

A 2017 study on 15-year olds from the United Kingdom found that the relationship between digital-screen time and self-reported mental wellbeing had a statistically significant quadratic relationship. Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag;

refs with no name must have content The local extremum in these quadratic trends indicate positive associations between well being and screen time below the extremum, and negative trends between well being and screen time above the extremum. These findings counter the displacement hypothesis and challenge the significance of observed negative effects of screen time on adolescents well being.

Investigations on the practical significance of statistically significant correlations between screen time and mental health reveal that the positive and negative impacts of screen time on mental well being account for 1% of variability in adolescent psychosocial outcomes. (In other words, more than 99% of variability in adolescent mental health is unrelated to digital screen time) [23]. There is a lack of an empirical standard to judge at what point the effect of screen time on mental health becomes an urgent matter. According to a study that analyzed caregiver perceptions of their child's well being in relation to their amount of screen time usage from the National Survey of Children’s Health, caregiver perceived a difference in their child's psychosocial functioning when the child engaged in over 4 hours of screen time per day[24]. The researchers consider this finding a possible benchmark on which to assess practically significant changes in well being. Future research on the benefits of moderate screen usage is encouraged to include examinations on the content of screen time and mental well being rather than the quantity of screen time on mental wellbeing.

Less is Better

Another theory known as the "less is better" approach postulates minimum screen time is optimal[25]. It emerged from evidence that screen time is sedentary and passive, which leads to physical and mental detriments. Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag;

refs with no name must have content

The benefits of educational screen time have challenged the less is better approach.

REGULATION

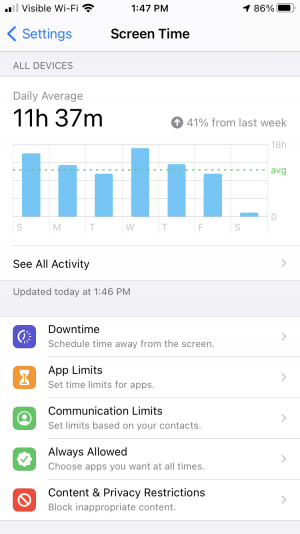

Successful approaches to regulate screen time have included behavioral self-imposed limitations, using non-digital means for as many tasks as possible to avoid interacting with screens, and using digital platforms in a mindful way[26]. Mindful digital habits are possible and studies regarding self-control will need to be consulted to make a further prescription.

Parents

Research shows that parents can effectively deter their children from partaking in excessing screen time. Parents' efforts to modulate screen-time have proven to be more impactful on adolescents than efforts from school teachers.[article today] Professor Manuel Jimenez, assistant professor in the Department of Pediatrics and director of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics Education at the Boggs Center on Developmental Disabilities at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School recommended implementing a family media plan that places time limits on media usage, identifies what media behaviors are appropriate, and designates media-free hours and locations of the house.[27] However, parents' influence on adolescents is subjective to the parents' screen usage. Parents with excessive leisure-related screen time usage were less likely to deter children from over-indulging in screen-time. Conversely, parents who modeled lower levels of screen-time are more likely to deter children from using TV or computer screens for more than 2 hours. [28]. The importance of moderating screen time is not realized by some parents. Some view screen related activities as having educational benefits for the child. Occupying children with screens has additional perceived benefits such as avoiding conflict with the child, allotting the parents time to complete other household tasks, and financial gains by displacement of other possibly costly activities.[29]

Medical Care Providers

The alarming correlation between screen-time and depression in adolescents has motivated researchers to turn to clinicians and medical providers to educate adolescents' on the dangers of excessive screen-time. As a primary point of contact to the healthcare system, care providers and nurses should screen any adolescent for negative consequences from excessive screen-use who report a higher screen-time than 2 hours per day, the recommended daily screen time usage administered by the American Academy of Pediatrics. Clear recommendations, behavioral contracts, and screen-time interventions are needed to guide adolescents' use of their time effectively. [article] The most updated criteria for assessing adolescent psychosocial health is HEADS4, which stands for Home environment, Education and employment, Eating, peer-related Activities, Drugs, Sexuality, Suicide/depression, Safety, and --newly added--Screen-Time. It has been helpful at opening a conversation between providers and patients regarding the addictiveness, risks, and repercussions of excessive screen-time use, specifically spent on social media. It is not widely used because care providers have reported the HEADS4 assessment adds 20 minutes to each patient visit which is too long to maintain their busy patient schedules. [article1]. Behavioral contracts between individual adolescents and her medical care provider regarding their screen-time usage grant the adolescent the autonomy to decide how many hours a day they would reduce their screen exposure. Evidence suggests when adolescents participate in rule-making, they are more likely to adopt initial behavior changes.

References

- ↑ Sanders, Taren et al. "Type Of Screen Time Moderates Effects On Outcomes In 4013 Children: Evidence From The Longitudinal Study Of Australian Children". International Journal Of Behavioral Nutrition And Physical Activity, vol 16, no. 1, 2019. Springer Science And Business Media LLC, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-019-0881-7.

- ↑ Taheri, Ehsaneh et al. "Association Of Physical Activity And Screen Time With Psychiatric Distress In Children And Adolescents: CASPIAN-IV Study". Journal Of Tropical Pediatrics, vol 65, no. 4, 2018, pp. 361-372. Oxford University Press (OUP), https://doi.org/10.1093/tropej/fmy063.

- ↑ Domingues-Montanari, Sophie. "Clinical And Psychological Effects Of Excessive Screen Time On Children". Journal Of Paediatrics And Child Health, vol 53, no. 4, 2017, pp. 333-338. Wiley, https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.13462.

- ↑ Rosenthal, Samantha R. et al. "Association Between Mobile Phone Screen Time And Depressive Symptoms Among College Students: A Threshold Effect". Human Behavior And Emerging Technologies, vol 3, no. 3, 2021, pp. 432-440. Wiley, https://doi.org/10.1002/hbe2.256.

- ↑ Taheri, Ehsaneh et al. "Association Of Physical Activity And Screen Time With Psychiatric Distress In Children And Adolescents: CASPIAN-IV Study". Journal Of Tropical Pediatrics, vol 65, no. 4, 2018, pp. 361-372. Oxford University Press (OUP), https://doi.org/10.1093/tropej/fmy063.

- ↑ LASSENIUS, O. et al. "Self-Reported Health And Physical Activity Among Community Mental Healthcare Users". Journal Of Psychiatric And Mental Health Nursing, vol 20, no. 1, 2012, pp. 82-90. Wiley, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2012.01951.x.

- ↑ Taheri, Ehsaneh et al. "Association Of Physical Activity And Screen Time With Psychiatric Distress In Children And Adolescents: CASPIAN-IV Study". Journal Of Tropical Pediatrics, vol 65, no. 4, 2018, pp. 361-372. Oxford University Press (OUP), https://doi.org/10.1093/tropej/fmy063.

- ↑ Taheri, Ehsaneh et al. "Association Of Physical Activity And Screen Time With Psychiatric Distress In Children And Adolescents: CASPIAN-IV Study". Journal Of Tropical Pediatrics, vol 65, no. 4, 2018, pp. 361-372. Oxford University Press (OUP), https://doi.org/10.1093/tropej/fmy063.

- ↑ Taheri, Ehsaneh et al. "Association Of Physical Activity And Screen Time With Psychiatric Distress In Children And Adolescents: CASPIAN-IV Study". Journal Of Tropical Pediatrics, vol 65, no. 4, 2018, pp. 361-372. Oxford University Press (OUP), https://doi.org/10.1093/tropej/fmy063.

- ↑ Gidwani, Pradeep P. et al. "Television Viewing And Initiation Of Smoking Among Youth". Pediatrics, vol 110, no. 3, 2002, pp. 505-508. American Academy Of Pediatrics (AAP), https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.110.3.505.

- ↑ Subramaniapillai, Mehala. "Physical Activity And Mental Health". Mental Health And Physical Activity, vol 7, no. 2, 2014, pp. 87-88. Elsevier BV, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhpa.2014.06.002.

- ↑ Domingues-Montanari, Sophie. "Clinical And Psychological Effects Of Excessive Screen Time On Children". Journal Of Paediatrics And Child Health, vol 53, no. 4, 2017, pp. 333-338. Wiley, https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.13462.

- ↑ Sanders, Taren et al. "Type Of Screen Time Moderates Effects On Outcomes In 4013 Children: Evidence From The Longitudinal Study Of Australian Children". International Journal Of Behavioral Nutrition And Physical Activity, vol 16, no. 1, 2019. Springer Science And Business Media LLC, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-019-0881-7.

- ↑ Sanders, Taren et al. "Type Of Screen Time Moderates Effects On Outcomes In 4013 Children: Evidence From The Longitudinal Study Of Australian Children". International Journal Of Behavioral Nutrition And Physical Activity, vol 16, no. 1, 2019. Springer Science And Business Media LLC, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-019-0881-7.

- ↑ Sanders, Taren et al. "Type Of Screen Time Moderates Effects On Outcomes In 4013 Children: Evidence From The Longitudinal Study Of Australian Children". International Journal Of Behavioral Nutrition And Physical Activity, vol 16, no. 1, 2019. Springer Science And Business Media LLC, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-019-0881-7.

- ↑ Sanders, Taren et al. "Type Of Screen Time Moderates Effects On Outcomes In 4013 Children: Evidence From The Longitudinal Study Of Australian Children". International Journal Of Behavioral Nutrition And Physical Activity, vol 16, no. 1, 2019. Springer Science And Business Media LLC, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-019-0881-7.

- ↑ Sanders, Taren et al. "Type Of Screen Time Moderates Effects On Outcomes In 4013 Children: Evidence From The Longitudinal Study Of Australian Children". International Journal Of Behavioral Nutrition And Physical Activity, vol 16, no. 1, 2019. Springer Science And Business Media LLC, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-019-0881-7.

- ↑ Sanders, Taren et al. "Type Of Screen Time Moderates Effects On Outcomes In 4013 Children: Evidence From The Longitudinal Study Of Australian Children". International Journal Of Behavioral Nutrition And Physical Activity, vol 16, no. 1, 2019. Springer Science And Business Media LLC, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-019-0881-7.

- ↑ Sanders, Taren et al. "Type Of Screen Time Moderates Effects On Outcomes In 4013 Children: Evidence From The Longitudinal Study Of Australian Children". International Journal Of Behavioral Nutrition And Physical Activity, vol 16, no. 1, 2019. Springer Science And Business Media LLC, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-019-0881-7.

- ↑ Sanders, Taren et al. "Type Of Screen Time Moderates Effects On Outcomes In 4013 Children: Evidence From The Longitudinal Study Of Australian Children". International Journal Of Behavioral Nutrition And Physical Activity, vol 16, no. 1, 2019. Springer Science And Business Media LLC, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-019-0881-7.

- ↑ Sanders, Taren et al. "Type Of Screen Time Moderates Effects On Outcomes In 4013 Children: Evidence From The Longitudinal Study Of Australian Children". International Journal Of Behavioral Nutrition And Physical Activity, vol 16, no. 1, 2019. Springer Science And Business Media LLC, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-019-0881-7.

- ↑ Przybylski, Andrew K., and Netta Weinstein. "A Large-Scale Test Of The Goldilocks Hypothesis". Psychological Science, vol 28, no. 2, 2017, pp. 204-215. SAGE Publications, https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797616678438.

- ↑ Przybylski, Andrew K. et al. "How Much Is Too Much? Examining The Relationship Between Digital Screen Engagement And Psychosocial Functioning In A Confirmatory Cohort Study". Journal Of The American Academy Of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, vol 59, no. 9, 2020, pp. 1080-1088. Elsevier BV, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2019.06.017.

- ↑ Przybylski, Andrew K. et al. "How Much Is Too Much? Examining The Relationship Between Digital Screen Engagement And Psychosocial Functioning In A Confirmatory Cohort Study". Journal Of The American Academy Of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, vol 59, no. 9, 2020, pp. 1080-1088. Elsevier BV, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2019.06.017.

- ↑ Sanders, Taren et al. "Type Of Screen Time Moderates Effects On Outcomes In 4013 Children: Evidence From The Longitudinal Study Of Australian Children". International Journal Of Behavioral Nutrition And Physical Activity, vol 16, no. 1, 2019. Springer Science And Business Media LLC, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-019-0881-7.

- ↑ Sanders, Taren et al. "Type Of Screen Time Moderates Effects On Outcomes In 4013 Children: Evidence From The Longitudinal Study Of Australian Children". International Journal Of Behavioral Nutrition And Physical Activity, vol 16, no. 1, 2019. Springer Science And Business Media LLC, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-019-0881-7.

- ↑ "The Daily Targum". The Daily Targum, 2022, https://dailytargum.com/article/2020/09/rutgers-expert-discusses-potential-solutions-for-managing-screen-time-among.

- ↑ Schoeppe, Stephanie et al. "How Is Adults’ Screen Time Behaviour Influencing Their Views On Screen Time Restrictions For Children? A Cross-Sectional Study". BMC Public Health, vol 16, no. 1, 2016. Springer Science And Business Media LLC, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-2789-3.

- ↑ Domingues-Montanari, Sophie. "Clinical And Psychological Effects Of Excessive Screen Time On Children". Journal Of Paediatrics And Child Health, vol 53, no. 4, 2017, pp. 333-338. Wiley, https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.13462.