Project Green Light

Project Green Light is a city-wide police surveillance system in Detroit, Michigan. The first public-private-community partnership of its kind,[1] Project Green Light Detroit utilizes police monitoring through high-resolution facial recognition cameras (1080p) whose images can be linked to the state of Michigan's facial recognition database, SNAP and law enforcement image databases. The project's aim is to deter and reduce city crime and is used in the pursuit of criminals., though it has been hotly contested due to its lack of transparency, community input and public support.

Contents

History

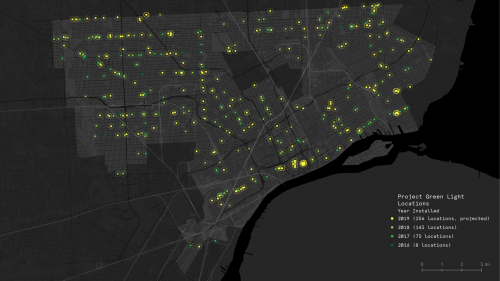

Launched January 1, 2016 with support from Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan, eight city gas station businesses were recruited by the Detroit Police Department with the assurance that the flashing green lights and cameras installed at each location would help identify criminal suspects in any future crimes, as well as helping lower neighborhood crime altogether.[2] With continued governmental and state support, Project Green Light expanded with the justification that Detroit Police Department data showed a decrease in criminal activity at the original eight locations. Since its inception, the number of institutions who pay for Project Green Light infrastructure has expanded to over 700 locations as of January, 2021.

These include schools, apartment complexes, restaurants and markets, medical centers, cathedrals and churches, laundromats, liquor stores and community centers.In 2017, the city of Detroit contracted a $1 million agreement with DataWorks Plus and began to implement their facial recognition software, FacePlus into Project Green Light technologies.[3] FacePlus can automatically search any face that enters the camera's field of vision and may assess them against statewide and law enforcement databases.

In 2019, the city of Detroit enacted a policy limiting the use of facial recognition software which prohibits the use of real-time surveillance and only allows police to use facial recognition during investigations of violent crimes and home invasions.[4] The policy requires at least two officers verify matches produced by the facial recognition software and imposes penalties for officers who abuse the technology.[5]

According to news sources in June 2020,[6] Project Green Light has allegedly been used on crowds in Black Lives Matter protests using supplemental facial recognition technology to identify protestors who did not adhere to social distancing protocols, a violation which carries up to a $1,000 fine. Project Green Light images have also been allegedly used to help police identify and locate further #BLM protestors whose immigration status was under question.[7]

Implementation

As a public-private partnership, Project Green Light is a paid service that Detroit businesses, residential complexes, schools, churches, and other institutions opt into willingly. Each participant of Project Green Light pays for installation of cameras, signage, decals and green lights to identify that they are part of the project. The cost of these materials for businesses ranges from $4,000 to $6,000.[8] The cameras which monitor buildings are strategically placed to capture license plates and faces of individuals at any given location. This footage from cameras is available 24/7 and until a policy change enacted by a civilian oversight body, The Detroit Board of Police Commissioners after series of public debates in 2019, was monitored and virtually patrolled by members of the police, analysts, and volunteers in-real time. These surveillance streams were not only available 24/7 on demand but were also available on mobile devices in real-time by police. Although the surveillance footage from Project Green Light is no longer monitored in-real time with facial recognition analyzed consistently, the constant capturing of footage at over 700 locations in Detroit means that for the majority of people, their identity can be matched to their footage in public spaces and city streets. Much of the surveillance monitoring work is done at Detroit's Real-Time Crime Center (RTCC), also launched in 2016 costing the city an initial $8 million with an additional $4 million for expansion in 2019.[9] The RTCC prioritizes Project Green Light affiliates over non-affiliates and works with such government agencies as the FBI, the Department of Homeland Security, and private partners including DTE and Rock Financial.[10] This purportedly enables rapid Detroit Police Department response to situations in-progress, which has been beneficial for proponents as a highly effective technological solution to crime in high-risk areas that can bring efficiencies into the investigative process.

Facial Recognition

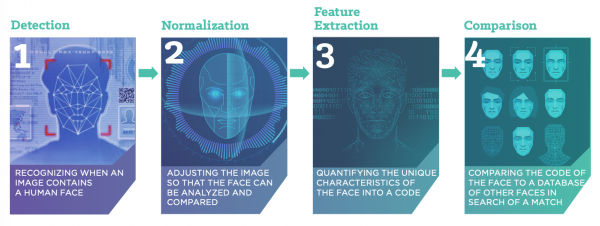

As an emerging technology, facial recognition has become widespread in public and private sectors before coordinated public policy discussions have commenced across the country. Facial recognition systems are used throughout shopping centers and grocery stores to track customer habits, by phones and security infrastructure to verify one's identity, and by police departments to determine the identity of suspects from video footage. Facial recognition is a biometric technology that uses distinguishable facial markers in images by comparing against a database of known individuals’ faces in order to match and identify an unknown person. Facial recognition systems generally have three elements: (1) video footage or photographs to be analyzed, (2) software to process captured images for comparison using algorithmic analysis, and (3) databases against which images can be compared. The system's main component is a set of algorithms that identify faces through extracting facial characteristics and comparing them to known faces in a pre-existing database. Facial recognition comprises the following steps: detection, normalization, feature extraction, and comparison. Detection means recognizing when an image contains a human face. Normalization means adjusting the image for analysis, feature extraction is the quantifying of facial characteristics of a given individual into code, and comparison means comparing that facial code to a database to search for a match. A 2019 study by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) found that false positive rates in face recognition algorithms are higher in women than men, and are highest in American Indian, African American and East Asian individuals within domestic law enforcement image databases.[11]

Concerns

Effectiveness

Project Green Light's effectiveness as a city crime-control measure however is unclear. Many question the legitimacy of the program and say that crime statistics used as evidence from the Detroit Police Chief are flawed. Some of these stats are: (1) Incidents of violent crime reduced by 48% (compared to 2015) at the original 8 PGL sites.[12] (2) Incidents of violent crime reduced by 23% (compared to 2015) at all Project Green Light sites.[13] (3) Carjackings have decreased by 20% in 2 years.[14] Detroit Community Technology Project has stated that the controversial effectiveness claims are due to too short of a sample size and/or too short of a time frame by researchers. Additionally, there have been no studies that compare Project Green Light locations with non Project locations. Due to this absence researchers say it is almost impossible to tie Detroit's crime reduction rates with Project Green Light specifically.

Civil Liberties

In the state of Michigan since 1999, every person taking a state ID has had their image added to a facial recognition database (SNAP). These images, along with a large repository of police databases with mugshots are used to profile those seen through Project Green Light video footage, and city activists expressed discontent with the practice of real-time monitoring and tracking through mobile devices, which culminated in a change to facial recognition policy, prohibiting the use of real-time surveillance and allowing the use of facial recognition only during violent crimes and home invasions.[15] Opponents of the project have raised objections that the technologies and methods in place violate the First, Fourth, and Fourteenth amendments. The use of facial recognition technology by law enforcement can potentially infringe on First Amendment rights, those of free speech and assembly. This could come about from facial recognition technologies implemented in community spaces or cities by depriving people of their ability to speak and gather anonymously, because of their knowledge that they are being watched, which could deter and limit people from engaging normally, specifically in places of worship across Detroit that employ Project Green Light.[16] Another constitutional issue which arises from facial recognition surveillance is whether identification through facial recognition constitutes unlawful search under the Fourth Amendment.

Algorithmic Bias

Algorithmic bias refers to statistical errors based on poorly composed datasets which provide an outcome to group A that differs from groups B, C or D. These outcomes generally perpetuate the legacies of exclusion and disproportionate advantage to some that have shaped our legal structures today. Algorithmic biases are in part due to human social norms and ideologies that are reflected back to us in our sociotechnical systems. The datasets that facial recognition systems are trained on present racial, gender and age bias that, if local governments implement for crime-control, requires full transparency to its citizens.

Historical Surveillance

Facial recognition is proven to be less effective for women and darker skinned individuals.[17] These demographic differentials mean that misidentification and wrongful accusation is much more likely to happen for individuals who have historically been heavily surveilled and profiled, furthering the displacement and unjust discrimination against people of color. Inaccuracies run the risk of negative consequences for innocent civilians who are misidentified. A U.S government study has shown that even the best facial recognition algorithms misidentify Blacks at five to ten times the rates of whites. In Detroit, at least two individuals, Michael Oliver and Robert Williams have been wrongly accused through Project Green Light surveillance technologies of involvement with crimes they had nothing to do with. Sociologist Ruha Benjamin has described contemporary biometric surveillance as a form of technologies used to support racist policies and practices through the tracking and control of Black people throughout American history.[18] Surveillance of Black bodies has a long history. The “lantern-laws” of 18th-century New York were a legal code that required Black and Indigenous people to illuminate themselves with a candle lantern when walking in streets after dark, so that slaves could be easily identified. The use of facial recognition on Detroit racial justice protestors has been criticized as a contemporary iteration of the counterintelligence COINTELPRO surveillance of Black activists and community organizers in the 1960s.[19] Video surveillance in Detroit, a city with an 78% Black population has been theorized as a continuing legacy of oppression. Introducing the use of this technology through Project Green Light makes this massive facial recognition experiment the first of its kind in on a concentration of Black citizens.

Security vs Safety

The idea that public security measures such as surveillance equates to public safety has led local governments to make problematic decisions that facilitate an outcome that many believe to be ineffective and unsafe for community members. Such policies, such as predictive policing, may disproportionately affect marginalized peoples (undocumented, formerly incarcerated, unhoused, poor, etc.) and minoritized populations.[20] The businesses that take part in Project Green Light pay thousands of dollars to create a culture of safety for their patrons. Most of these patrons and business owners are not Detroit residents themselves.

Health and Well-Being

The effects of mass surveillance on a population include fear, mistrust, paranoia, anxiety, and erosion of identity. The feeling of being watched, even at one's residence or religious institution can stifle authentic expression, deteriorate communal relationships, and promote loss of faith in government. Specifically for Detroiter's, these harms compound with state neglect, lack of metal health resources, displacement and environmental hazards such as pollution. Project Green Light's actual blinking green light located at every participating structure serves as a deterrent for community members walking by wishing for privacy, for residents in homes who still bear witness to the bright light shining through their windows, blinded. These are costs on the people of Detroit, not on the business owners who live outside of the city.

References

- ↑ Project Green Light Detroit. City of Detroit. (n.d.). Retrieved January 25, 2023, from https://detroitmi.gov/departments/police-department/project-green-light-detroit

- ↑ Campbell, Eric T.; Howell, Shea; House, Gloria; & Petty, Tawana (eds.). (2019, August). Special Issue: Detroiters want to be seen, not watched. Riverwise. The Riverwise Collective.

- ↑ A critical summary of Detroit’s Project Green Light and its greater context. (n.d.). Retrieved January 26, 2023, from https://detroitcommunitytech.org/system/tdf/librarypdfs/DCTP_PGL_Report.pdf?file=1%26type=node%26id=77%26force=

- ↑ Facial recognition - national league of cities. (n.d.). Retrieved February 6, 2023, from https://www.nlc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/NLC-Facial-Recognition-Report.pdf

- ↑ Cwiek, Detroit Police Commissioners Approve Facial Recognition Policy

- ↑ WXYZ-TV Detroit | Channel 7. (2020). Future of Facial Recognition Technology. Retrieved January 25, 2023, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h-3_cTPqKI4.

- ↑ Race, policing, and Detroit's Project Green Light. UM ESC. (2020, June 25). Retrieved January 25, 2023, from https://esc.umich.edu/project-green-light/

- ↑ Project Green Light Detroit. City of Detroit. (n.d.). Retrieved January 25, 2023, from https://detroitmi.gov/departments/police-department/project-green-light-detroit

- ↑ Detroit real-time crime center. Atlas of Surveillance. (n.d.). Retrieved January 27, 2023, from https://atlasofsurveillance.org/real-time-crime-centers/detroit-real-time-crime-center

- ↑ City of Detroit. Detroit Police Commissioners Meeting 04 19 2018. DetroitMI.gov. [Online] April 19, 2018. [Cited: June 5, 2019.] http://video.detroitmi.gov/CablecastPublicSite/show/5963?channel=3.

- ↑ Grother, Patrick J., et al. “Part 3: Demographic Effects” Face Recognition Vendor Test (FRVT). U.S. Dept. of Commerce, National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2014.

- ↑ Project Green Light Detroit. [Online] 2019. [Cited: June 4, 2019.] https://detroitmi.gov/departments/police-department/project-green-light- detroit.

- ↑ Project Green Light Detroit. [Online] 2019. [Cited: June 4, 2019.] https://detroitmi.gov/departments/police-department/project-green-light- detroit.

- ↑ Livengood, Chad. Detroit aims to mandate Project Green Light crime- monitoring surveillance for late-night businesses. Crain's Detroit Business. January 3, 2018.

- ↑ Facial recognition - national league of cities. (n.d.). Retrieved February 6, 2023, from https://www.nlc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/NLC-Facial-Recognition-Report.pdf

- ↑ Hamann, H. et al. (2019, Spring). Facial Recognition Technology: Where Will It Take Us? The American Bar Association, Criminal Justice Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.americanbar.org/ groups/criminal_justice/publications/criminal-justice-magazine/2019/spring/facial-recognition- technology/.

- ↑ Buolamwini, J., & Gebru, T. (2018, January 21). Gender shades: Intersectional accuracy disparities in commercial gender classification. PMLR. Retrieved January 27, 2023, from http://proceedings.mlr.press/v81/buolamwini18a.html

- ↑ Benjamin, R. (2020). Race after technology: Abolitionist Tools for the new jim code. Polity.

- ↑ FBI COINTELPRO Surveillance Files for February-May 1971, Covering Nation of Islam, Black Panther Party, National Committee to Combat Fascism, JOMO, Eldridge Cleaver, Huey Newton, Pittsburgh NAACP Branch, Angela Davis, and Stokely Carmichael.

- ↑ Shapiro, Aaron. Reform predictive policing. Nature. January 25, 2017, Vol. 541, pp. 458-460.