Project Green Light

Project Green Light is a city-wide police surveillance system in Detroit, Michigan. The first public-private-community partnership of its kind,[1] Project Green Light utilizes police monitoring through high-resolution facial recognition cameras (1080p) whose images can be linked to the state of Michigan's facial recognition database, SNAP and country-wide law enforcement image databases. The project's aim is to deter and reduce city crime and is used in the pursuit of criminals. Its methods have been questioned and challenged due to its lack of transparency, community input, and public support.

Contents

History

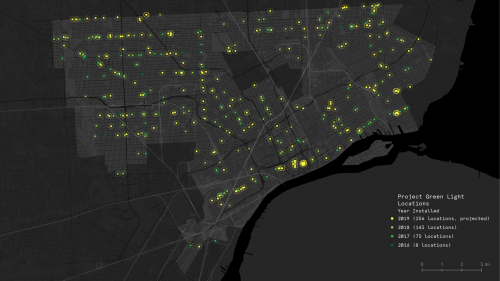

Launched January 1, 2016 with support from Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan, eight city gas station businesses were recruited by the Detroit Police Department with the assurance that the flashing green lights and surveillance cameras installed at each location would help identify criminal suspects in any future crimes, as well as help to lower neighborhood crime altogether.[2] With continued governmental and state support, Project Green Light expanded with the justification that Detroit Police Department data showed a decrease in criminal activity at the original eight locations. Since its inception, the number of institutions who pay for Project Green Light infrastructure has expanded to over 700 locations as of January, 2021.

These include schools, apartment complexes, restaurants and markets, medical centers, cathedrals and churches, laundromats, liquor stores and community centers.In 2017, the city of Detroit contracted a $1 million agreement with DataWorks Plus and began to implement their facial recognition software, FacePlus into Project Green Light technologies.[3] FacePlus can automatically search any face that enters the camera's field of vision and may assess them against statewide and law enforcement databases.

In 2019, the city of Detroit enacted a policy limiting the use of facial recognition software which prohibits the use of real-time surveillance and only allows police to use facial recognition during investigations of violent crimes and home invasions.[4] The policy requires at least two officers verify matches produced by the facial recognition software and imposes penalties for officers who abuse the technology.[5]

According to news sources in June 2020,[6] Project Green Light has allegedly been used on crowds in Black Lives Matter protests using facial recognition technology to identify protestors who did not adhere to social distancing protocols which at the time was a violation that carried up to a $1,000 fine. Project Green Light images have also been allegedly used to help police identify and locate further Black Lives Matter protestors whose immigration status was under question.[7]

Implementation

As a public-private partnership, Project Green Light is a paid service that Detroit businesses, residential complexes, schools, churches, and other institutions opt into willingly. Each participant of Project Green Light pays for installation of cameras, signage, decals and green lights to identify that they are part of the project. The cost of these materials for businesses ranges from $4,000 to $6,000.[8] The cameras which monitor buildings are strategically placed to capture license plates and faces of individuals at any given location. The cameras run 24/7 and until a policy change brought about after series of public debates in 2019, the Detroit Board of Police Commissioners - a civilian oversight body - enforced limits on the use of facial recognition technology in real-time. These surveillance streams were not only available 24/7 on demand but were also available on mobile devices for police use. Although the surveillance footage from Project Green Light is no longer monitored in real-time with facial recognition used and analyzed consistently, the constant capturing of video at over 700 locations in Detroit means that for the majority of people, their identity can be matched to footage in public spaces and in city streets. Surveillance footage monitoring and virtual patrolling is done by members of the police, analysts, and volunteers. Much of the monitoring work is done at Detroit's Real-Time Crime Center (RTCC), also launched in 2016 costing the city an initial $8 million with an additional $4 million for expansion in 2019.[9] The RTCC prioritizes Project Green Light affiliates over non-affiliates and works with such government agencies as the FBI, the Department of Homeland Security, and private partners including DTE and Rock Financial.[10] This purportedly enables rapid Detroit Police Department response to situations in-progress, which has been beneficial for proponents as a highly effective technological solution to crime in high-risk areas that can bring efficiencies into the investigative process.

Facial Recognition

As an emerging technology, facial recognition has become widespread in public and private sectors before coordinated public policy discussions have commenced across the country. Facial recognition systems are used throughout shopping centers and grocery stores to track customer habits, by phones and security infrastructure to verify one's identity, and by police departments to determine the identity of suspects from video footage. Facial recognition is a biometric technology that uses distinguishable facial markers in images by comparing against a database of known individuals’ faces in order to match and identify an unknown person. Facial recognition systems generally have three elements: (1) video footage or photographs to be analyzed (2) software to process captured images for comparison using algorithmic analysis, and (3) databases against which images can be compared.[11]

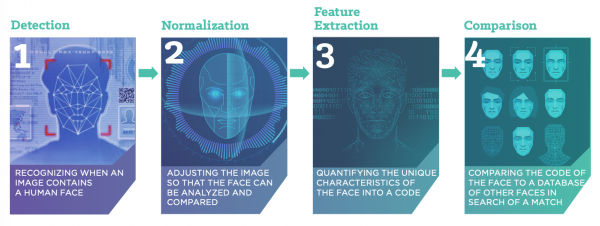

The system's main component is a set of algorithms that identify faces through extracting facial characteristics and comparing them to known faces in a pre-existing database. Facial recognition comprises the following steps: detection, normalization, feature extraction, and comparison. Detection means recognizing when an image contains a human face. Normalization means adjusting the image for analysis, feature extraction is the quantifying of facial characteristics of a given individual into code, and comparison means comparing that facial code to a database to search for a match. A 2019 study by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) found that false positive rates in face recognition algorithms are higher in women than men, and are highest in American Indian, African American and East Asian individuals within domestic law enforcement image databases.[12]

Concerns

Effectiveness

Project Green Light's effectiveness as a city crime-control measure has not been researched in-depth. Many question the legitimacy of the program and say that crime statistics used as evidence from the Detroit Police Chief are flawed. These statistics include: (1) Incidents of violent crime reduced by 48% (compared to 2015) at the original 8 PGL sites, (2) Incidents of violent crime reduced by 23% (compared to 2015) at all Project Green Light sites[13] and, (3) Carjackings have decreased by 20% in 2 years.[14]

Detroit Community Technology Project has stated that the controversial effectiveness claims are due to too short of a sample size and too short of a time frame by researchers. Additionally, there have been no studies that compare Project Green Light locations with non-project locations. Due to this absence, researchers say it is almost impossible to tie Detroit's crime reduction rates with Project Green Light specifically. This raises the question of whether Project Green Light is justified as a public safety measure. More crime statistics on the effectiveness of the project are being awaited.

Civil Liberties

In the state of Michigan since 1999, every person taking a state ID has had their image added to a facial recognition database (SNAP). These images, along with a large repository of police databases with mugshots, are used to profile those seen through Project Green Light video footage. Opponents of the project have raised objections that the technologies and methods in place violate the First and Fourth Amendments. The use of facial recognition technology by law enforcement can potentially infringe on First Amendment rights, those of free speech and assembly. This could come about from facial recognition technologies implemented in community spaces and cities by depriving people of their ability to speak and gather anonymously, due to the knowledge that they are being watched, which could deter and limit people from engaging normally, specifically in places of worship across Detroit that employ Project Green Light.[15] Facial recognition technology used by the police as an investigative tool, especially in public protests as in the Detroit Black Lives Matter marches in 2020 and the 2016 use on pictures in social media to identify and arrest Baltimore protestors after Freddy Gray Jr.'s death[16] have raised further concerns of the violation of First Amendment rights by police in their use of facial recognition. Widespread and pervasive use of facial recognition technology such as Project Green Light's city-wide program could be interpreted as a transgression on First amendment rights to free speech and assembly.

Another constitutional issue which arises from facial recognition surveillance is whether identification through facial recognition constitutes unlawful search under the Fourth Amendment which protects people from unlawful police searches when they have reasonable expectation of privacy. Because many residents and visitors of Detroit are unaware of the measures that Project Green Light takes to surveil institutions and businesses located all over the city, their privacy rights may be violated without them ever being aware. The use of facial recognition technology as a crime-control measure in a public safety context does however uphold to Fourth Amendment guidelines of the expectation of privacy in a public setting - if entered. Because Project Green Light cameras are not only inside buildings but outside capturing street views, this complicates matters for what counts as reasonable expectation of privacy in such a setting.

Algorithmic Bias

Algorithmic bias refers to statistical errors based on poorly composed datasets which provide an outcome to one group that differs from other groups. Specifically, representation bias is a key feature of facial recognition software. Representation bias comes about from the categorization and sampling of a population on which a model is trained, under-represents and in turn cannot generalize well for certain subsets of the population. This is the case in facial recognition software used to assess individuals captured by Project Green Light which does not assess East Asian, African American and American Indian populations as accurately as European individuals. The technology is inherently flawed due to the training datasets used in algorithmic models which analyze facial codes inaccurately. These outcomes generally perpetuate the legacies of exclusion and disproportionate advantage to some that have shaped our legal structures today. Algorithmic biases are in part due to human social norms and ideologies that are reflected back to us in our sociotechnical systems. The datasets that facial recognition systems are trained on present racial, gender and age bias that, if local governments implement for crime-control, requires full transparency to its citizens.

Historical Surveillance

Facial recognition is proven to be less effective for women and darker skinned individuals.[17] These demographic differentials mean that misidentification and wrongful accusation is much more likely to happen for individuals who have historically been heavily surveilled and profiled, furthering the displacement and unjust discrimination against people of color. Inaccuracies run the risk of negative consequences for innocent civilians who are misidentified. In Detroit, at least two individuals, Michael Oliver and Robert Williams have been wrongly accused through Project Green Light surveillance technologies of involvement with crimes they had nothing to do with. Sociologist Ruha Benjamin has described contemporary biometric surveillance as a form of technologies used to support racist policies and practices through the tracking and control of Black people throughout American history.[18] Surveillance of Black bodies has a long history. The “lantern-laws” of 18th-century New York were a legal code that required Black and Indigenous people to illuminate themselves with a candle lantern when walking in streets after dark so that slaves could be easily identified. The use of facial recognition on Detroit racial justice protestors has been criticized as a contemporary iteration of the counterintelligence COINTELPRO surveillance of Black activists and community organizers in the 1960s.[19] Video surveillance in Detroit, a city with an 78% Black population[20] has been theorized as a continuing legacy of oppression. Introducing the use of this technology through Project Green Light makes this massive facial recognition experiment the first of its kind in on a concentration of Black citizens.

Security vs Safety

The idea that public security measures such as surveillance equates to public safety has led local governments to make problematic decisions that facilitate an outcome that many believe to be ineffective and unsafe for community members. Such policies, such as predictive policing, may disproportionately affect marginalized peoples (undocumented, formerly incarcerated, unhoused, poor, etc.) and minoritized populations.[21] The businesses that take part in Project Green Light pay thousands of dollars to create a culture of safety for their patrons. Most of these patrons and business owners are not Detroit residents themselves. Digital surveillance techniques, especially facial recognition software, have been considered by some social and surveillance theorists to be contemporary iterations of targeted racial surveillance, promoted under the guise of public safety. This justification in many cases serves as a moral cover which obfuscates the real and potential risks involved in the employment of such technologies, including the dehumanization of being misidentified and questioned by police, being wrongfully arrested, and having one's privacy rights violated in efforts to enforce legal punishment. Facial recognition software holds the negative potential to aid in the criminalization of women, Asian, Black, and Indigenous peoples through its inaccurate algorithms which misidentify these demographics disproportionately.

Health and Well-Being

The effects of mass surveillance on a population include fear, mistrust, paranoia, anxiety, and erosion of identity. The feeling of being watched, even at one's residence or religious institution can stifle authentic expression, deteriorate communal relationships, and promote loss of faith in government. Specifically for Detroiters, these harms compound with state neglect, lack of metal health resources, displacement, and environmental hazards such as pollution. Project Green Light's blinking green lights located at every participating structure serves as a deterrent for community members walking by expecting privacy, and for residents in homes who bear witness to the bright light shining through their windows incessantly. These are costs on the people of Detroit, not on business owners who live outside of the city. Social theorist and psychiatrist Frantz Fanon remarks that the embodied psychic effects of closed-circuit television (CCTV) surveillance in the United States includes nervous tensions, insomnia, fatigue, accidents, lightheadedness, and less control over reflexes.[22] The psychological impacts of active surveillance have been more commonly researched in public health, and less attention has been given to current mass surveillance tactics employed in public spaces. This research is critical as surveillance technology rapidly and covertly expands throughout the globe.

References

- ↑ Project Green Light Detroit. City of Detroit. (n.d.). Retrieved January 25, 2023, from https://detroitmi.gov/departments/police-department/project-green-light-detroit

- ↑ Campbell, Eric T.; Howell, Shea; House, Gloria; & Petty, Tawana (eds.). (2019, August). Special Issue: Detroiters want to be seen, not watched. Riverwise. The Riverwise Collective.

- ↑ A critical summary of Detroit’s Project Green Light and its greater context. (n.d.). Retrieved January 26, 2023, from https://detroitcommunitytech.org/system/tdf/librarypdfs/DCTP_PGL_Report.pdf?file=1%26type=node%26id=77%26force=

- ↑ Facial recognition - national league of cities. (n.d.). Retrieved February 6, 2023, from https://www.nlc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/NLC-Facial-Recognition-Report.pdf

- ↑ Cwiek, Detroit Police Commissioners Approve Facial Recognition Policy

- ↑ WXYZ-TV Detroit | Channel 7. (2020). Future of Facial Recognition Technology. Retrieved January 25, 2023, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h-3_cTPqKI4.

- ↑ Race, policing, and Detroit's Project Green Light. UM ESC. (2020, June 25). Retrieved January 25, 2023, from https://esc.umich.edu/project-green-light/

- ↑ Project Green Light Detroit. City of Detroit. (n.d.). Retrieved January 25, 2023, from https://detroitmi.gov/departments/police-department/project-green-light-detroit

- ↑ Detroit real-time crime center. Atlas of Surveillance. (n.d.). Retrieved January 27, 2023, from https://atlasofsurveillance.org/real-time-crime-centers/detroit-real-time-crime-center

- ↑ City of Detroit. Detroit Police Commissioners Meeting 04 19 2018. DetroitMI.gov. [Online] April 19, 2018. [Cited: June 5, 2019.] http://video.detroitmi.gov/CablecastPublicSite/show/5963?channel=3.

- ↑ Facial recognition - national league of cities. (n.d.). Retrieved February 6, 2023, from https://www.nlc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/NLC-Facial-Recognition-Report.pdf

- ↑ Grother, Patrick J., et al. “Part 3: Demographic Effects” Face Recognition Vendor Test (FRVT). U.S. Dept. of Commerce, National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2014.

- ↑ Project Green Light Detroit. [Online] 2019. [Cited: June 4, 2019.] https://detroitmi.gov/departments/police-department/project-green-light detroit.

- ↑ Livengood, Chad. Detroit aims to mandate Project Green Light crime- monitoring surveillance for late-night businesses. Crain's Detroit Business. January 3, 2018.

- ↑ Hamann, H. et al. (2019, Spring). Facial Recognition Technology: Where Will It Take Us? The American Bar Association, Criminal Justice Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.americanbar.org/ groups/criminal_justice/publications/criminal-justice-magazine/2019/spring/facial-recognition- technology/.

- ↑ Brandom, R. (2016, October 11). Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram Surveillance Tool Was Used to Arrest Baltimore Protestors. The Verge. Retrieved from https://www.theverge. com/2016/10/11/13243890/facebook-twitter-instagram-police-surveillance-geofeedia-api.

- ↑ Buolamwini, J., & Gebru, T. (2018, January 21). Gender shades: Intersectional accuracy disparities in commercial gender classification. PMLR. Retrieved January 27, 2023, from http://proceedings.mlr.press/v81/buolamwini18a.html

- ↑ Benjamin, R. (2020). Race after technology: Abolitionist Tools for the new jim code. Polity.

- ↑ FBI COINTELPRO Surveillance Files for February-May 1971, Covering Nation of Islam, Black Panther Party, National Committee to Combat Fascism, JOMO, Eldridge Cleaver, Huey Newton, Pittsburgh NAACP Branch, Angela Davis, and Stokely Carmichael.

- ↑ U.S. Census Bureau quickfacts: Detroit City, Michigan; United States. (n.d.). Retrieved February 10, 2023, from https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/detroitcitymichigan,US/PST045221

- ↑ Shapiro, Aaron. Reform predictive policing. Nature. January 25, 2017, Vol. 541, pp. 458-460.

- ↑ Brown, Simone. Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness. Duke University Press, 2015. 6.