Difference between revisions of "Music piracy"

(→Digital Millennium Copyright Act) |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File:music-pirates.jpg|400px|thumbnail|right]] | [[File:music-pirates.jpg|400px|thumbnail|right]] | ||

| − | '''Music piracy''' is a type of [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Copyright_infringement copyright infringement] defined by activities involving illegal downloading, copying, and distribution of music. Music piracy effectively circumvents the standard process of legally acquiring music released by artists through an official platform like [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ITunes iTunes] or [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spotify Spotify]. Consumers are able to obtain the music they want without having to be dependent on the authorized music distributors themselves, | + | '''Music piracy''' is a type of [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Copyright_infringement copyright infringement] defined by activities involving the illegal downloading, copying, and distribution of music. Music piracy effectively circumvents the standard process of legally acquiring music released by artists through an official platform like [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ITunes iTunes] or [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spotify Spotify]. Consumers are able to obtain the music they want without having to be dependent on the authorized music distributors themselves. However, the industry experiences harm, as a result, in the form of losses in revenues, wages, taxes, and jobs.<ref>Kalken, E., [https://theses.ubn.ru.nl/bitstream/handle/123456789/2067/Kalken%2c_E.C.J._1.pdf?sequence=1 "Piracy and Innovation in the Media Industries"], July 2016</ref> Music piracy has remained a contentious battle between the music industry and consumers since the early stages of musical documentation. There have been a number of legal issues brought up regarding the piracy of music. While it is widely known as a [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Victimless_crime "victimless crime"], music piracy is a point of ethical concern regarding anonymity, plagiarism, and online virtues. |

==History== | ==History== | ||

| − | Music piracy is a phenomenon | + | Music piracy is a phenomenon that has been observed before the invention of the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Internet Internet], but it was impossible to exist on such a large scale until the Internet prompted a profound improvement in music accessibility. During the first half of the 20th century, piracy was ubiquitous but hidden from the public eye. Due to lack of federal protection over sound recording, bootleggers recorded live performances and redistributed recordings in a manner that was technically not illegal until 1973.<ref name="Cummings"/> Music piracy derived from sound recordings became more common during the rock counterculture era of the 1960s. Famous bootlegged rock albums include [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bob_Dylan Bob Dylan]’s "Great White Wonder" (1969) which featured high-quality recordings of unreleased songs, and [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Rolling_Stones The Rolling Stones]’ "Live’r Than You’ll Ever Be" (1969), from an audience recording of their concert in Oakland, CA.<ref>“Bootleg Recording.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 8 Feb. 2019, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bootleg_recording.</ref> This insurgency prompted in the United States a copyright policy change during the 1970s. |

====1990's==== | ====1990's==== | ||

| − | During the 1990s, the United States observed the extreme extent to which piracy could impact the music industry. Coinciding with increased mainstream computer usage, music piracy in the form of [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peer-to-peer peer-to-peer] (P2P) MP3 file-sharing platforms became incredibly easy and accessible for anyone with basic computer skills. [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Napster Napster], a notable P2P technology, was created in 1999 by Shawn Fanning and Sean Parker, and reportedly reached 80 million registered users.<ref>Harris, Mark. “The History of Napster: Yes, It's Still Around.” Lifewire, Lifewire, 23 Jan. 2019, www.lifewire.com/history-of-napster-2438592.</ref> Despite its popularity, Napster quickly received legal backlash; the RIAA and musicians [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dr._Dre Dr. Dre] and [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metallica Metallica] sued Napster and won. | + | During the 1990s, the United States observed the extreme extent to which piracy could impact the music industry. Coinciding with increased mainstream computer usage, music piracy in the form of [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peer-to-peer peer-to-peer] (P2P) MP3 file-sharing platforms became incredibly easy to use and accessible for anyone with basic computer skills. [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Napster Napster], a notable P2P technology, was created in 1999 by Shawn Fanning and Sean Parker, and reportedly reached 80 million registered users.<ref>Harris, Mark. “The History of Napster: Yes, It's Still Around.” Lifewire, Lifewire, 23 Jan. 2019, www.lifewire.com/history-of-napster-2438592.</ref> Despite its popularity, Napster quickly received legal backlash as it likely caused a reduction in record sales; the RIAA and musicians like [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dr._Dre Dr. Dre] and [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metallica Metallica] sued Napster and won. |

====2000's until Today==== | ====2000's until Today==== | ||

| − | In 2011, Napster was acquired by Rhapsody from [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Best_Buy Best Buy] and now provides on-demand music to brands like [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/IHeartRadio iHeartRadio].<ref>“Napster.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 11 Mar. 2019, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Napster.</ref> Beyond basic MP3 file sharing, P2P sites were also utilized to leak albums before they were officially released to the public. Bennie Lydell “Dell” Glover, an employee at a CD manufacturing plant in North Carolina became notorious for single handedly smuggling hundreds of pop and rap CDs | + | In 2011, Napster was acquired by Rhapsody from [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Best_Buy Best Buy] and now provides on-demand music to brands like [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/IHeartRadio iHeartRadio].<ref>“Napster.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 11 Mar. 2019, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Napster.</ref> Beyond basic MP3 file sharing, P2P sites were also utilized to [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Internet_leak leak] albums before they were officially released to the public. Bennie Lydell “Dell” Glover, an employee at a CD manufacturing plant in North Carolina became notorious for single-handedly smuggling hundreds of pop and rap CDs out of the factory and sharing them on the P2P file-sharing site [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rabid_Neurosis Rabid Neurosis] (RNS). It is estimated that nearly 2,000 albums were leaked on RNS around the turn of the century, most of which came from this North Carolina plant.<ref name="Empire">Empire, Kitty. “Stephen Witt: 'Music Piracy Is Illegal – but Morally, Is It Wrong?'.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 7 June 2015, www.theguardian.com/books/2015/jun/07/filesharing-stephen-witt-how-music-got-free-interview.</ref> Artists such as Jay Z, Eminem, Mary J Blige, Kanye West, and Mariah Carey had their music leaked on RNS as a result of Glover’s actions. |

| − | In more recent history, the Music Consumer Insight Report of 2018 reflects the prevalence of music piracy in the modern era. The report revealed that “38% (of those surveyed) consume music through copyright infringement”<ref>Music Consumer Insight Report 2018. International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI), 2018, pp. 8–8, Music Consumer Insight Report 2018.</ref> and found that the majority download their music through stream-ripping, cyberlockers, or P2P. However, the present system for acquiring music through legal constraints is not necessarily without critique. Spotify, with 87 million paid subscribers,<ref>Gartenberg, Chaim. “Spotify Hits 87 Million Paid Subscribers.” The Verge, 1 Nov. 2018, www.theverge.com/2018/11/1/18051658/spotify-paid-subscribers-q3-earnings-update-87-million.</ref> has been accused of being a legal version of what Napster and the like once were, the argument being that with minimal fees for unlimited music consumption, the price of music is | + | In more recent history, the Music Consumer Insight Report of 2018 reflects on the prevalence of music piracy in the modern era. The report revealed that “38% (of those surveyed) consume music through copyright infringement”<ref>Music Consumer Insight Report 2018. International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI), 2018, pp. 8–8, Music Consumer Insight Report 2018.</ref> and found that the majority download their music through stream-ripping, cyberlockers, or P2P. However, the present system for acquiring music through legal constraints is not necessarily without critique. Spotify, with 87 million paid subscribers,<ref>Gartenberg, Chaim. “Spotify Hits 87 Million Paid Subscribers.” The Verge, 1 Nov. 2018, www.theverge.com/2018/11/1/18051658/spotify-paid-subscribers-q3-earnings-update-87-million.</ref> has been accused of being a legal version of what Napster and the like once were, the argument being that with minimal fees for unlimited music consumption, the price of music is effectively free.<ref>Quora. “Is Music Piracy Still A Problem?” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 3 Dec. 2018, www.forbes.com/sites/quora/2018/12/03/is-music-piracy-still-a-problem/#d57665c76104.</ref> |

==Legality== | ==Legality== | ||

While the US Constitution explicitly states intentions “to promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries”<ref>U.S. Constitution. Art./Amend. XIII, Sec. 8.</ref>, music was not originally considered a product that warranted protection under this copyright umbrella for almost half a century. The running list of copyright protected products in the U.S. (which originally contained books, maps, and charts) failed to include music until 1831, and sound recordings until 1972.<ref name = "Cummings">Cummings, Alex Sayf. “The Long History of Music Piracy.” Learn Liberty, 20 Apr. 2017, www.learnliberty.org/blog/the-long-history-of-music-piracy/.</ref> With the Copyright Act of 1909, published work became ‘protected’ and composers/musicians earned a flat rate [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Royalty_payment royalty payment] when their music was recorded. During this time, reproducing specific musical compositions (similar to creating covers) without the consent of the original composer remained legal. | While the US Constitution explicitly states intentions “to promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries”<ref>U.S. Constitution. Art./Amend. XIII, Sec. 8.</ref>, music was not originally considered a product that warranted protection under this copyright umbrella for almost half a century. The running list of copyright protected products in the U.S. (which originally contained books, maps, and charts) failed to include music until 1831, and sound recordings until 1972.<ref name = "Cummings">Cummings, Alex Sayf. “The Long History of Music Piracy.” Learn Liberty, 20 Apr. 2017, www.learnliberty.org/blog/the-long-history-of-music-piracy/.</ref> With the Copyright Act of 1909, published work became ‘protected’ and composers/musicians earned a flat rate [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Royalty_payment royalty payment] when their music was recorded. During this time, reproducing specific musical compositions (similar to creating covers) without the consent of the original composer remained legal. | ||

====Sound Recording Act of 1971==== | ====Sound Recording Act of 1971==== | ||

| − | Sound recordings remained unprotected until the "Sound Recording Act of 1971", which extended federal protection to prohibit piracy of phonograms.<ref>“Sound Recording Act of 1971.” The IT Law Wiki, itlaw.wikia.com/wiki/Sound_Recording_Act_of_1971.</ref> As | + | Sound recordings remained unprotected until the "Sound Recording Act of 1971" was passed, which extended federal protection to prohibit piracy of phonograms.<ref>“Sound Recording Act of 1971.” The IT Law Wiki, itlaw.wikia.com/wiki/Sound_Recording_Act_of_1971.</ref> As an amendment to the Copyright Act, the Sound Recording Act of 1971 included sound recordings (any work that resulted from the fixation of a series of musical, spoken, or other sounds) as copyrightable works<ref name="Halp">Halpern, M., [https://heinonline.org/HOL/Page?collection=journals&handle=hein.journals/gwlr40&id=991&men_tab=srchresults "Sound Recording Act of 1971: An End to Piracy on the High C's"], 1971</ref> The Act also legally clarified the difference between original works and reproductions of those works, stating that only the copyright holder had the authority and right to reproduce and distribute the sound recordings. Despite the efforts of the Act to protect sound recordings or the collection of sounds stored on a reproduction, the Sound Recording Act of 1971 was broad in scope and allowed for the exploitation of certain loopholes.<ref name="Halp"/> In 1973, the "[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Goldstein_v._California Goldenstein v. California]" Supreme Court case, in effect, ruled that beyond federal policy, states maintained the right to expand copyright protection of sound recordings through their own anti-piracy laws.<ref>“Goldstein v. California.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 13 Oct. 2018, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Goldstein_v._California.</ref> |

====Copyright Act of 1976==== | ====Copyright Act of 1976==== | ||

| − | + | The "[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Copyright_Act_of_1976 Copyright Act of 1976]" explicitly laid out copyright protections and terms of fair use, successfully replacing its 1909 predecessor. Most notably, this Act extended the length of protection to cover the life of the author plus an additional 50 years.<ref>“Copyright Act of 1976.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 3 Mar. 2019, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Copyright_Act_of_1976.</ref> The "Copyright Act of 1976" also put in place a static 75-year protection. This law, serving as Title 17 of the United States Code,<ref>“Copyright Law of the United States.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 14 Mar. 2019, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Copyright_law_of_the_United_States.</ref> remains as the basis of American copyright laws today. | |

| − | Since the late 90’s the criminalization of music piracy has intensified. Now, depending on the severity of the violation, the case can be handled as a civil lawsuit (resulting in thousands of dollars in fines), or result in criminal charges which could leave the defendant with a felony record, up to 5 years of jail time, and/or up to $250,000 in fines.<ref>“About Piracy.” RIAA, www.riaa.com/resources-learning/about-piracy/.</ref> | + | Since the late '90’s the criminalization of music piracy has intensified. Now, depending on the severity of the violation, the case can be handled as a civil lawsuit (resulting in thousands of dollars in fines), or result in criminal charges - which could leave the defendant with a felony record, up to 5 years of jail time, and/or up to $250,000 in fines.<ref>“About Piracy.” RIAA, www.riaa.com/resources-learning/about-piracy/.</ref> |

====Digital Millennium Copyright Act==== | ====Digital Millennium Copyright Act==== | ||

| − | The [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Digital_Millennium_Copyright_Act Digital Millennium Copyright Act] of 1998 deals with the greater world of copyright infringement on the web. This act targets those who create and spread technology which allows users to circumvent measures surrounding works which have been copyrighted. Additionally, this act, signed into law by President Bill Clinton, increased the preexisting penalties for the offense of copyright infringement on the internet. | + | The [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Digital_Millennium_Copyright_Act Digital Millennium Copyright Act] of 1998 deals with the greater world of copyright infringement on the web. This act targets those who create and spread technology which allows users to circumvent measures surrounding works which have been copyrighted. Additionally, this act, signed into law by President Bill Clinton, increased the preexisting penalties for the offense of copyright infringement on the internet. This Act has served as a the foundation for future legislation that similarly aims to prevent music piracy online. |

====Online Piracy Act==== | ====Online Piracy Act==== | ||

| − | In 2011, the "[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stop_Online_Piracy_Act Stop Online Piracy Act]" (SOPA) was introduced by [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lamar_Smith U.S. Representative Lamar S. Smith] (R-TX) | + | In 2011, the "[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stop_Online_Piracy_Act Stop Online Piracy Act]" (SOPA) was introduced by [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lamar_Smith U.S. Representative Lamar S. Smith] (R-TX). The intention was to combat online piracy and counterfeit trafficking with higher intensity, with strong support from the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Recording_Industry_Association_of_America Recording Industry Association of America] (RIAA). Proponents of SOPA argued that it would "protect IP and industry, jobs, and revenue" and was necessary to improve copyright law enforcement, especially with respect to foreign companies and websites. The bill received bipartisan support in the House of Representatives and the Senate, in addition to other Associations and Legislatures. Opposition to the bill included arguments that the threat to free speech allowed law enforcement to Unconstitutionally block access to Internet domains due to infringement of copyright by content. In addition, opponents mentioned that SOPA would bypass "safe harbor" protections from liability, which is protected by the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Digital_Millennium_Copyright_Act Digital Millennium Copyright Act] as well as pushback from library associations. The bill was never passed after receiving widespread public backlash in the form of online protest from companies like [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Google Google] and [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/English_Wikipedia English Wikipedia].<ref>“Stop Online Piracy Act.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 7 Mar. 2019, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stop_Online_Piracy_Act.</ref> |

==Social Media== | ==Social Media== | ||

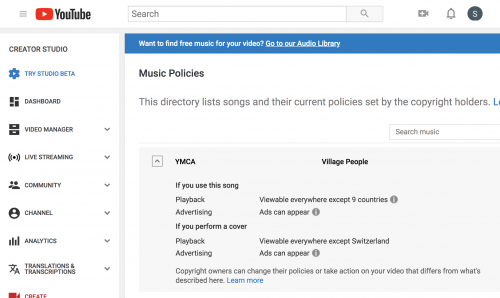

[[File:Youtubemusicsfh.png|thumbnail|500px|YouTube's Music Policy for the song YMCA by Village People]] | [[File:Youtubemusicsfh.png|thumbnail|500px|YouTube's Music Policy for the song YMCA by Village People]] | ||

| − | New social media platforms that allow for audio and video | + | New social media platforms that allow for the creation and dissemination of audio and video - by the average person - have unleashed a wide range of music copyright problems. Seeing as anyone can upload a video to YouTube, Facebook, or Instagram (and such content often includes music) these platforms have been forced to create policy to protect copyright laws. |

| − | '''YouTube''' has | + | '''YouTube''' has a comprehensive [https://www.youtube.com/music_policies music policy] of its own that details the policies on individual songs. For example, the use of certain songs in videos can cause the videos to be blocked in certain countries or can cause the video to generate specific advertisements. This policy also reserves the right for any artist to take action against a video that includes his/her music. YouTube divides music copyright into two categories; sound recordings and musical composition. Sound recordings refer to audio recordings belonging to the performer or producer while musical composition refers to the actual music or lyrics belonging to composers or lyricists. <ref> "Know how music rights are managed on YouTube" Youtube Creators. YouTube. https://creatoracademy.youtube.com/page/lesson/artist-copyright#strategies-zippy-link-1 </ref> |

'''Instagram''' has been known to stop live video streams due to copyrighted music being played in the background. To avoid music piracy, one of Instagram's new features allows users to add the "music sticker" to their stories for music that has given Instagram the right to be used. <ref> "Introducing Music in Stories". Instagram Info Center. 28 June 2018. Instagram. https://instagram-press.com/blog/2018/06/28/introducing-music-in-stories/ </ref> | '''Instagram''' has been known to stop live video streams due to copyrighted music being played in the background. To avoid music piracy, one of Instagram's new features allows users to add the "music sticker" to their stories for music that has given Instagram the right to be used. <ref> "Introducing Music in Stories". Instagram Info Center. 28 June 2018. Instagram. https://instagram-press.com/blog/2018/06/28/introducing-music-in-stories/ </ref> | ||

'''Facebook''' | '''Facebook''' | ||

| − | When uploading a video to Facebook, Facebook will take several seconds to scan for | + | When uploading a video to Facebook, Facebook will take several seconds to scan for illegally distributed music. Facebook has planned to release a lip-syncing feature, where there will be hundreds of songs available, much like the app [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Musical.ly Musical.ly]. Facebook will pay artists and singers whose music is available on the platform. <ref> https://techcrunch.com/2018/06/05/facebook-lip-sync-live/ "Facebook allows videos with copyrighted music, tests Lip Sync Live" Josh Constine, 2019. </ref> Similarly to Instagram, Facebook will not post the video if there are copyright issues with the background music. |

'''Twitter''' | '''Twitter''' | ||

| − | Twitter's recent [https://help.twitter.com/en/rules-and-policies/fair-use-policy fair use policy] has | + | Twitter's recent [https://help.twitter.com/en/rules-and-policies/fair-use-policy fair use policy] has lead to the suspension of many accounts on the platform. Violations of this policy include how much of the copied work was used, the amount of work copied from the original author, and whether or not it affected the original work or the author. This policy is taken from the "fair use" American doctrine limiting the use of copyrighted material without having permission from the original author. <ref> "Fair use". Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 14 April 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fair_use </ref> Users who see their copyrighted material used without permission can file a complaint with Twitter, and the formal complaint will be sent to the user who posted the content, along with removal of the tweet and potential account suspension. |

| − | There are many websites that recommend ways to circumvent the flagging or removal of content | + | There are many websites that recommend ways to circumvent the flagging or removal of content containing copyrighted music on social media. The most common recommendation is to adjust the audio, such as changing the pitch so that the audio is not recognized by the platform's algorithm. |

==Ethical Implications== | ==Ethical Implications== | ||

| − | ===The Polarization=== | + | ===The Polarization of Music Piracy=== |

====A Pirate's Justification==== | ====A Pirate's Justification==== | ||

| − | + | Today, music consumers frequently download their music illegally despite the serious legal consequences currently in place. Some justify their actions by citing their [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/First_Amendment_to_the_United_States_Constitution First Amendment rights].<ref>“The Ethics of Piracy.” Stanford Computer Science, cs.stanford.edu/people/eroberts/cs181/projects/1999-00/software-piracy/ethical.html.</ref> Others have claimed that they enjoy pirating music because of the addictive "rush" it provides rather than out of actual financial necessity.<ref name="Empire"/> Many perceive the offense of music piracy to be more comparable to trespassing than theft since piracy does not prevent others from accessing the music. Rather, music piracy simply circumvents the legal process and redefines who has access to music.<ref>Barry, Christian. “Is Downloading Really Stealing? The Ethics of Digital Piracy.” The Conversation, 25 Feb. 2019, theconversation.com/is-downloading-really-stealing-the-ethics-of-digital-piracy-39930.</ref> | |

| − | The legal consequences following music piracy are also widely criticized due to its | + | The legal consequences following music piracy are also widely criticized due to its (unwarranted) intense nature, in which defendants with minimal violations have been made examples of and forced to pay enormous fines.<ref>Rolling Stone. “Minnesota Woman Ordered to Pay $222,000 in Music Piracy Case.” Rolling Stone, 12 Sept. 2012, www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/minnesota-woman-ordered-to-pay-222000-in-music-piracy-case-236366/.</ref> |

====An Artist's Defense==== | ====An Artist's Defense==== | ||

| − | In defense of the artists, some consider music piracy to be far from a victimless crime and have played vocal roles in their opposition. Since the 90s, the RIAA has | + | In defense of the artists, some consider music piracy to be far from a victimless crime and have played vocal roles in their opposition. Since the '90s, the RIAA has served as the leading opponent to music piracy, following the introduction of P2P MP3 file sharing, and has been taking consistent legal actions against this supposed malpractice. Though the extent to which music piracy affects established musicians is up for debate, many musicians argue that this illegal sharing of music devalues their art, rendering their work free. People who hold this perspective widely consider music piracy and unofficial music leaks as theft of an artist's property - or as theft of an artist's control over his/her own works. <still needs citations> |

===Implications of Technological Advancement=== | ===Implications of Technological Advancement=== | ||

| − | + | James Moor, a professor of intellectual and moral philosophy, argues that as technology proliferates and evolves, its ethical implications (and impact) only increase.<ref>Moor, J.H. Ethics Inf Technol (2005) 7: 111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10676-006-0008-0</ref> In the case of music piracy, the ease, and frequency at which music can be illegally recorded, copied, and/or distributed is positively correlated to the ever-increasing capabilities and accessibility of technology. For example, the rise of computers as a common household object in the 1990's prompted the emergence of P2P MP3 file sharing, which - in turn - generated an entirely new set of ethical implications. The technological advancement leading to an expansion of user capabilities often warrants an updated ethical evaluation. Even further, Moor writes that “situations arise in which we do not have adequate policies in place to guide us. We are confronted with policy vacuums”<ref>Moor, James. H. 2005. “Why We Need Better Ethics for Emerging Technologies,” Ethics and Information Technology 7:111-119.</ref>. Given the speed at which technological innovation takes place, it is crucial that we frequently revisit, evaluate and refine our current policies. | |

===Impact of Online Anonymity=== | ===Impact of Online Anonymity=== | ||

| − | Often, | + | Often, offenders of music piracy are successful at remaining anonymous, and, therefore, are able to avoid legal consequences. As Wallace discusses in ''Online Anonymity,''<ref>Wallace, K.A. Ethics and Information Technology (1999) 1: 21. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010066509278</ref> the ability for an online agent to maintain their anonymity can lessen their degree of accountability. Moreover, with a reduced sense of personal accountability, individuals become more willing to justify operating outside of legal constraints and are still able to maintain a clear conscience. In theory, if a given crime is not associated with the criminal (for lack of a better word), then the crime cannot reflect poorly on them. If a large portion of consumers behave this way, the music industry is sure to experience a sizable loss in revenue. |

| − | As Wallace discusses in ''Online Anonymity,''<ref>Wallace, K.A. Ethics and Information Technology (1999) 1: 21. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010066509278</ref> the ability for an online agent to maintain their anonymity can lessen their degree of accountability. | + | |

===Reflection of Online Virtues=== | ===Reflection of Online Virtues=== | ||

| − | + | In ''Social Networking Virtues'', Shannon Vallor emphasizes that personal values are often obscured in an online context.<ref>Vallor, S. Ethics Inf Technol (2010) 12: 157. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10676-009-9202-1</ref> Technology can provide a platform to fully embody, contradict, or fabricate one's personal values (e.g., honesty and empathy). Though most music pirates likely would not consider themselves "thieves" or "criminals," the disconnect that an online context brings, in effect, distances the perpetrators from their offense. The current era of online music piracy with countless P2P file sharing sites provides a platform for individuals to act in contradiction to their values, for better or for worse. | |

=== Profit Deducting Plagiarism=== | === Profit Deducting Plagiarism=== | ||

| − | The unauthorized distribution of pirated work through | + | The unauthorized distribution of pirated work through online file sharing systems, such as BitTorrent and Napster (1999-2001), are environments in which the grounds for copyright infringement of expression is not a deception. The distributor of the original file is aware of the act of redistributing the original content under their permission and the recipient is also aware that the source of the file is not from the original creator. This form of plagiarism on the ground of directly benefiting from the source of the original content while harming the creator of the content through economic means.<ref>“The Handbook of Information and Computer Ethics - The Handbook of Information and Computer Ethics.” Wiley Online Library, onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/9780470281819.</ref> |

| − | Ultimately, the contentious and timeless battle of music piracy comes down to the idea of ownership: | + | Ultimately, the contentious and timeless battle of music piracy comes down to the idea of ownership: who owns art, who has the right to share it, and how might individuals gain access to it. |

==See Also== | ==See Also== | ||

Revision as of 18:59, 18 April 2019

Music piracy is a type of copyright infringement defined by activities involving the illegal downloading, copying, and distribution of music. Music piracy effectively circumvents the standard process of legally acquiring music released by artists through an official platform like iTunes or Spotify. Consumers are able to obtain the music they want without having to be dependent on the authorized music distributors themselves. However, the industry experiences harm, as a result, in the form of losses in revenues, wages, taxes, and jobs.[1] Music piracy has remained a contentious battle between the music industry and consumers since the early stages of musical documentation. There have been a number of legal issues brought up regarding the piracy of music. While it is widely known as a "victimless crime", music piracy is a point of ethical concern regarding anonymity, plagiarism, and online virtues.

History

Music piracy is a phenomenon that has been observed before the invention of the Internet, but it was impossible to exist on such a large scale until the Internet prompted a profound improvement in music accessibility. During the first half of the 20th century, piracy was ubiquitous but hidden from the public eye. Due to lack of federal protection over sound recording, bootleggers recorded live performances and redistributed recordings in a manner that was technically not illegal until 1973.[2] Music piracy derived from sound recordings became more common during the rock counterculture era of the 1960s. Famous bootlegged rock albums include Bob Dylan’s "Great White Wonder" (1969) which featured high-quality recordings of unreleased songs, and The Rolling Stones’ "Live’r Than You’ll Ever Be" (1969), from an audience recording of their concert in Oakland, CA.[3] This insurgency prompted in the United States a copyright policy change during the 1970s.

1990's

During the 1990s, the United States observed the extreme extent to which piracy could impact the music industry. Coinciding with increased mainstream computer usage, music piracy in the form of peer-to-peer (P2P) MP3 file-sharing platforms became incredibly easy to use and accessible for anyone with basic computer skills. Napster, a notable P2P technology, was created in 1999 by Shawn Fanning and Sean Parker, and reportedly reached 80 million registered users.[4] Despite its popularity, Napster quickly received legal backlash as it likely caused a reduction in record sales; the RIAA and musicians like Dr. Dre and Metallica sued Napster and won.

2000's until Today

In 2011, Napster was acquired by Rhapsody from Best Buy and now provides on-demand music to brands like iHeartRadio.[5] Beyond basic MP3 file sharing, P2P sites were also utilized to leak albums before they were officially released to the public. Bennie Lydell “Dell” Glover, an employee at a CD manufacturing plant in North Carolina became notorious for single-handedly smuggling hundreds of pop and rap CDs out of the factory and sharing them on the P2P file-sharing site Rabid Neurosis (RNS). It is estimated that nearly 2,000 albums were leaked on RNS around the turn of the century, most of which came from this North Carolina plant.[6] Artists such as Jay Z, Eminem, Mary J Blige, Kanye West, and Mariah Carey had their music leaked on RNS as a result of Glover’s actions.

In more recent history, the Music Consumer Insight Report of 2018 reflects on the prevalence of music piracy in the modern era. The report revealed that “38% (of those surveyed) consume music through copyright infringement”[7] and found that the majority download their music through stream-ripping, cyberlockers, or P2P. However, the present system for acquiring music through legal constraints is not necessarily without critique. Spotify, with 87 million paid subscribers,[8] has been accused of being a legal version of what Napster and the like once were, the argument being that with minimal fees for unlimited music consumption, the price of music is effectively free.[9]

Legality

While the US Constitution explicitly states intentions “to promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries”[10], music was not originally considered a product that warranted protection under this copyright umbrella for almost half a century. The running list of copyright protected products in the U.S. (which originally contained books, maps, and charts) failed to include music until 1831, and sound recordings until 1972.[2] With the Copyright Act of 1909, published work became ‘protected’ and composers/musicians earned a flat rate royalty payment when their music was recorded. During this time, reproducing specific musical compositions (similar to creating covers) without the consent of the original composer remained legal.

Sound Recording Act of 1971

Sound recordings remained unprotected until the "Sound Recording Act of 1971" was passed, which extended federal protection to prohibit piracy of phonograms.[11] As an amendment to the Copyright Act, the Sound Recording Act of 1971 included sound recordings (any work that resulted from the fixation of a series of musical, spoken, or other sounds) as copyrightable works[12] The Act also legally clarified the difference between original works and reproductions of those works, stating that only the copyright holder had the authority and right to reproduce and distribute the sound recordings. Despite the efforts of the Act to protect sound recordings or the collection of sounds stored on a reproduction, the Sound Recording Act of 1971 was broad in scope and allowed for the exploitation of certain loopholes.[12] In 1973, the "Goldenstein v. California" Supreme Court case, in effect, ruled that beyond federal policy, states maintained the right to expand copyright protection of sound recordings through their own anti-piracy laws.[13]

Copyright Act of 1976

The "Copyright Act of 1976" explicitly laid out copyright protections and terms of fair use, successfully replacing its 1909 predecessor. Most notably, this Act extended the length of protection to cover the life of the author plus an additional 50 years.[14] The "Copyright Act of 1976" also put in place a static 75-year protection. This law, serving as Title 17 of the United States Code,[15] remains as the basis of American copyright laws today.

Since the late '90’s the criminalization of music piracy has intensified. Now, depending on the severity of the violation, the case can be handled as a civil lawsuit (resulting in thousands of dollars in fines), or result in criminal charges - which could leave the defendant with a felony record, up to 5 years of jail time, and/or up to $250,000 in fines.[16]

Digital Millennium Copyright Act

The Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998 deals with the greater world of copyright infringement on the web. This act targets those who create and spread technology which allows users to circumvent measures surrounding works which have been copyrighted. Additionally, this act, signed into law by President Bill Clinton, increased the preexisting penalties for the offense of copyright infringement on the internet. This Act has served as a the foundation for future legislation that similarly aims to prevent music piracy online.

Online Piracy Act

In 2011, the "Stop Online Piracy Act" (SOPA) was introduced by U.S. Representative Lamar S. Smith (R-TX). The intention was to combat online piracy and counterfeit trafficking with higher intensity, with strong support from the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA). Proponents of SOPA argued that it would "protect IP and industry, jobs, and revenue" and was necessary to improve copyright law enforcement, especially with respect to foreign companies and websites. The bill received bipartisan support in the House of Representatives and the Senate, in addition to other Associations and Legislatures. Opposition to the bill included arguments that the threat to free speech allowed law enforcement to Unconstitutionally block access to Internet domains due to infringement of copyright by content. In addition, opponents mentioned that SOPA would bypass "safe harbor" protections from liability, which is protected by the Digital Millennium Copyright Act as well as pushback from library associations. The bill was never passed after receiving widespread public backlash in the form of online protest from companies like Google and English Wikipedia.[17]

Social Media

New social media platforms that allow for the creation and dissemination of audio and video - by the average person - have unleashed a wide range of music copyright problems. Seeing as anyone can upload a video to YouTube, Facebook, or Instagram (and such content often includes music) these platforms have been forced to create policy to protect copyright laws.

YouTube has a comprehensive music policy of its own that details the policies on individual songs. For example, the use of certain songs in videos can cause the videos to be blocked in certain countries or can cause the video to generate specific advertisements. This policy also reserves the right for any artist to take action against a video that includes his/her music. YouTube divides music copyright into two categories; sound recordings and musical composition. Sound recordings refer to audio recordings belonging to the performer or producer while musical composition refers to the actual music or lyrics belonging to composers or lyricists. [18]

Instagram has been known to stop live video streams due to copyrighted music being played in the background. To avoid music piracy, one of Instagram's new features allows users to add the "music sticker" to their stories for music that has given Instagram the right to be used. [19]

Facebook When uploading a video to Facebook, Facebook will take several seconds to scan for illegally distributed music. Facebook has planned to release a lip-syncing feature, where there will be hundreds of songs available, much like the app Musical.ly. Facebook will pay artists and singers whose music is available on the platform. [20] Similarly to Instagram, Facebook will not post the video if there are copyright issues with the background music.

Twitter Twitter's recent fair use policy has lead to the suspension of many accounts on the platform. Violations of this policy include how much of the copied work was used, the amount of work copied from the original author, and whether or not it affected the original work or the author. This policy is taken from the "fair use" American doctrine limiting the use of copyrighted material without having permission from the original author. [21] Users who see their copyrighted material used without permission can file a complaint with Twitter, and the formal complaint will be sent to the user who posted the content, along with removal of the tweet and potential account suspension.

There are many websites that recommend ways to circumvent the flagging or removal of content containing copyrighted music on social media. The most common recommendation is to adjust the audio, such as changing the pitch so that the audio is not recognized by the platform's algorithm.

Ethical Implications

The Polarization of Music Piracy

A Pirate's Justification

Today, music consumers frequently download their music illegally despite the serious legal consequences currently in place. Some justify their actions by citing their First Amendment rights.[22] Others have claimed that they enjoy pirating music because of the addictive "rush" it provides rather than out of actual financial necessity.[6] Many perceive the offense of music piracy to be more comparable to trespassing than theft since piracy does not prevent others from accessing the music. Rather, music piracy simply circumvents the legal process and redefines who has access to music.[23]

The legal consequences following music piracy are also widely criticized due to its (unwarranted) intense nature, in which defendants with minimal violations have been made examples of and forced to pay enormous fines.[24]

An Artist's Defense

In defense of the artists, some consider music piracy to be far from a victimless crime and have played vocal roles in their opposition. Since the '90s, the RIAA has served as the leading opponent to music piracy, following the introduction of P2P MP3 file sharing, and has been taking consistent legal actions against this supposed malpractice. Though the extent to which music piracy affects established musicians is up for debate, many musicians argue that this illegal sharing of music devalues their art, rendering their work free. People who hold this perspective widely consider music piracy and unofficial music leaks as theft of an artist's property - or as theft of an artist's control over his/her own works. <still needs citations>

Implications of Technological Advancement

James Moor, a professor of intellectual and moral philosophy, argues that as technology proliferates and evolves, its ethical implications (and impact) only increase.[25] In the case of music piracy, the ease, and frequency at which music can be illegally recorded, copied, and/or distributed is positively correlated to the ever-increasing capabilities and accessibility of technology. For example, the rise of computers as a common household object in the 1990's prompted the emergence of P2P MP3 file sharing, which - in turn - generated an entirely new set of ethical implications. The technological advancement leading to an expansion of user capabilities often warrants an updated ethical evaluation. Even further, Moor writes that “situations arise in which we do not have adequate policies in place to guide us. We are confronted with policy vacuums”[26]. Given the speed at which technological innovation takes place, it is crucial that we frequently revisit, evaluate and refine our current policies.

Impact of Online Anonymity

Often, offenders of music piracy are successful at remaining anonymous, and, therefore, are able to avoid legal consequences. As Wallace discusses in Online Anonymity,[27] the ability for an online agent to maintain their anonymity can lessen their degree of accountability. Moreover, with a reduced sense of personal accountability, individuals become more willing to justify operating outside of legal constraints and are still able to maintain a clear conscience. In theory, if a given crime is not associated with the criminal (for lack of a better word), then the crime cannot reflect poorly on them. If a large portion of consumers behave this way, the music industry is sure to experience a sizable loss in revenue.

Reflection of Online Virtues

In Social Networking Virtues, Shannon Vallor emphasizes that personal values are often obscured in an online context.[28] Technology can provide a platform to fully embody, contradict, or fabricate one's personal values (e.g., honesty and empathy). Though most music pirates likely would not consider themselves "thieves" or "criminals," the disconnect that an online context brings, in effect, distances the perpetrators from their offense. The current era of online music piracy with countless P2P file sharing sites provides a platform for individuals to act in contradiction to their values, for better or for worse.

Profit Deducting Plagiarism

The unauthorized distribution of pirated work through online file sharing systems, such as BitTorrent and Napster (1999-2001), are environments in which the grounds for copyright infringement of expression is not a deception. The distributor of the original file is aware of the act of redistributing the original content under their permission and the recipient is also aware that the source of the file is not from the original creator. This form of plagiarism on the ground of directly benefiting from the source of the original content while harming the creator of the content through economic means.[29]

Ultimately, the contentious and timeless battle of music piracy comes down to the idea of ownership: who owns art, who has the right to share it, and how might individuals gain access to it.

See Also

References

- ↑ Kalken, E., "Piracy and Innovation in the Media Industries", July 2016

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Cummings, Alex Sayf. “The Long History of Music Piracy.” Learn Liberty, 20 Apr. 2017, www.learnliberty.org/blog/the-long-history-of-music-piracy/.

- ↑ “Bootleg Recording.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 8 Feb. 2019, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bootleg_recording.

- ↑ Harris, Mark. “The History of Napster: Yes, It's Still Around.” Lifewire, Lifewire, 23 Jan. 2019, www.lifewire.com/history-of-napster-2438592.

- ↑ “Napster.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 11 Mar. 2019, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Napster.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Empire, Kitty. “Stephen Witt: 'Music Piracy Is Illegal – but Morally, Is It Wrong?'.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 7 June 2015, www.theguardian.com/books/2015/jun/07/filesharing-stephen-witt-how-music-got-free-interview.

- ↑ Music Consumer Insight Report 2018. International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI), 2018, pp. 8–8, Music Consumer Insight Report 2018.

- ↑ Gartenberg, Chaim. “Spotify Hits 87 Million Paid Subscribers.” The Verge, 1 Nov. 2018, www.theverge.com/2018/11/1/18051658/spotify-paid-subscribers-q3-earnings-update-87-million.

- ↑ Quora. “Is Music Piracy Still A Problem?” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 3 Dec. 2018, www.forbes.com/sites/quora/2018/12/03/is-music-piracy-still-a-problem/#d57665c76104.

- ↑ U.S. Constitution. Art./Amend. XIII, Sec. 8.

- ↑ “Sound Recording Act of 1971.” The IT Law Wiki, itlaw.wikia.com/wiki/Sound_Recording_Act_of_1971.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Halpern, M., "Sound Recording Act of 1971: An End to Piracy on the High C's", 1971

- ↑ “Goldstein v. California.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 13 Oct. 2018, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Goldstein_v._California.

- ↑ “Copyright Act of 1976.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 3 Mar. 2019, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Copyright_Act_of_1976.

- ↑ “Copyright Law of the United States.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 14 Mar. 2019, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Copyright_law_of_the_United_States.

- ↑ “About Piracy.” RIAA, www.riaa.com/resources-learning/about-piracy/.

- ↑ “Stop Online Piracy Act.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 7 Mar. 2019, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stop_Online_Piracy_Act.

- ↑ "Know how music rights are managed on YouTube" Youtube Creators. YouTube. https://creatoracademy.youtube.com/page/lesson/artist-copyright#strategies-zippy-link-1

- ↑ "Introducing Music in Stories". Instagram Info Center. 28 June 2018. Instagram. https://instagram-press.com/blog/2018/06/28/introducing-music-in-stories/

- ↑ https://techcrunch.com/2018/06/05/facebook-lip-sync-live/ "Facebook allows videos with copyrighted music, tests Lip Sync Live" Josh Constine, 2019.

- ↑ "Fair use". Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 14 April 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fair_use

- ↑ “The Ethics of Piracy.” Stanford Computer Science, cs.stanford.edu/people/eroberts/cs181/projects/1999-00/software-piracy/ethical.html.

- ↑ Barry, Christian. “Is Downloading Really Stealing? The Ethics of Digital Piracy.” The Conversation, 25 Feb. 2019, theconversation.com/is-downloading-really-stealing-the-ethics-of-digital-piracy-39930.

- ↑ Rolling Stone. “Minnesota Woman Ordered to Pay $222,000 in Music Piracy Case.” Rolling Stone, 12 Sept. 2012, www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/minnesota-woman-ordered-to-pay-222000-in-music-piracy-case-236366/.

- ↑ Moor, J.H. Ethics Inf Technol (2005) 7: 111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10676-006-0008-0

- ↑ Moor, James. H. 2005. “Why We Need Better Ethics for Emerging Technologies,” Ethics and Information Technology 7:111-119.

- ↑ Wallace, K.A. Ethics and Information Technology (1999) 1: 21. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010066509278

- ↑ Vallor, S. Ethics Inf Technol (2010) 12: 157. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10676-009-9202-1

- ↑ “The Handbook of Information and Computer Ethics - The Handbook of Information and Computer Ethics.” Wiley Online Library, onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/9780470281819.