Difference between revisions of "Libraries and Ethical Information Technology"

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | Libraries, as a branch of information science, are being affected by changes in the information landscape.<ref>Kim | + | Libraries, as a branch of information science, are being affected by changes in the information landscape.<ref name="Kim">Kim, Bohyun. “Moving Forward with Digital Disruption: What Big Data, IoT, Synthetic Biology, AI, Blockchain, and Platform Businesses Mean to Libraries.” <i>Library Technology Reports</i>, vol. 56, no. 2, 2020, doi:10.5860/ltr.56n2.</ref> Libraries are concerned with the research, curation, and dispensation of information. In recent years, the world has seen the emergence of Big Data and evolving technology. Ethical dilemmas arise as the traditional card catalog system is eschewed in favor of more technology-driven software, such as the Integrated Library System. Additionally, Big Data and the Internet of Things (IOT) are introducing unique questions about patron privacy and information protection in libraries. Lastly, libraries face the ethical implications of information classification and cataloging processes. |

== History == | == History == | ||

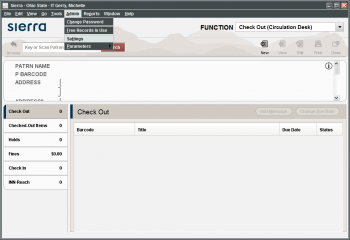

| − | Through information technology advancement, libraries have experienced diverse effects that are increasing dependencies on modern tools. Prior to the 1960s, much of the information handling in libraries was manual, hands-on, and self-contained | + | Through information technology advancement, libraries have experienced diverse effects that are increasing dependencies on modern tools. Prior to the 1960s, much of the information handling in libraries was manual, hands-on, and self-contained; however, with the introduction of the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Integrated_library_system Integrated Library System (ILS)], this began to change.<ref name="Prindle">Prindle, Sarah and Amber Loos. “Information Ethics and Academic Libraries: Data Privacy in the Era of Big Data.” <i>Journal of Information Ethics</i>, vol. 26, no. 2, Fall 2017, pp. 22-33.</ref> While ILSes are an organizational construct, they commonly consist of database storage and other software features.<ref>“Integrated”</ref> For example, a program like [https://www.iii.com/products/sierra-ils/ Sierra] that allows library employees to search for a patron’s account and view all materials they currently have borrowed is a feature of the ILS. [[File:Sierra_Checkout.png|350px|thumbnail|right|Example of patron account on Sierra (source: https://library.osu.edu/site/it/customize-your-sierra-display-settings/)]] In the past, this would have been stored physically, if at all. As the technology landscape is changing, the ethical commitment to protect patron privacy has not been revised. This commitment to protection includes not only patrons’ personal information, but data on information for which they are searching. From the American Library Association Code of Ethics: “We protect each library user's right to privacy and confidentiality with respect to information sought or received and resources consulted, borrowed, acquired or transmitted.”<ref>“Professional Ethics”</ref> Libraries are also adding more electronic resources; some, like Prindle and Loos, argue that adding these services is essential to the survival of libraries.<ref name="Prindle"></ref> Additionally, a strong tie to the IOT, RFID technology, is a semi-recent addition to libraries, primarily used to check library materials in and out.<ref name="Kim"></ref> |

== Big Data and Library Ethics == | == Big Data and Library Ethics == | ||

| − | As libraries collect and dispense a wider range of data, there is more discussion about the role and responsibility of libraries in relation to Big Data. Academic libraries specifically may be storing information such as full names, social security numbers, and demographics.<ref> | + | As libraries collect and dispense a wider range of data, there is more discussion about the role and responsibility of libraries in relation to Big Data. Academic libraries specifically may be storing information such as full names, social security numbers, and demographics.<ref name="Prindle"></ref> In software, completely ruling out data leaks is not possible, so inherent risks exist as libraries of any type use these systems and store sensitive information. The question has been posed, is it in violation of the aforementioned Code of Ethics to retain the information if data leaks are possible at all?<ref name="Prindle"></ref> Additionally, as libraries add resources like e-book resources or database access to help adapt to changing community needs, they are associating with Big Data companies which some argue presents ethical challenges because Big Data is, at its core, a profit industry. For example, in 2016, it was discovered that a popular e-book company used by libraries was collecting personal information.<ref name="Prindle"></ref> These decisions and incidents demonstrate the ethics of how patron information is no longer merely handled by librarians, but also the third-party companies they use. The role of libraries in this new landscape is discussed as well. Bohyun Kim, an associate professor at the University of Rhode Island as well as their Chief Technology Officer, proposes that an ethical challenge of libraries in the information technology age is providing a space for people to reconnect with their values and remember the importance of physical interaction, hopefully informing ethical use of non-neutral technology.<ref name="Kim"></ref> |

== Ethical Classification == | == Ethical Classification == | ||

| − | Libraries also face challenges in ethical classification practices. The Library of Congress Classification (LCC) and the Dewey Decimal Classification (DDC) have both experienced accusations of perpetuating stereotypes or biases. Specifically, the Library of Congress experienced requests for reform over the term “illegal alien” as a search term in the online catalog, and the original version of the Dewey Decimal Classification has been questioned over a large percentage of classification being dedicated to Christianity over other religions.<ref>Noble | + | Libraries also face challenges in ethical classification practices. The Library of Congress Classification (LCC) and the Dewey Decimal Classification (DDC) have both experienced accusations of perpetuating stereotypes or biases. Specifically, the Library of Congress experienced requests for reform over the term “illegal alien” as a search term in the online catalog, and the original version of the Dewey Decimal Classification has been questioned over a large percentage of classification being dedicated to Christianity over other religions.<ref name="Noble">Noble, Safiya Umoja. <i>Algorithms of Oppression</i>. E-book, New York UP, 2018.</ref> The LCC and DDC are widely used classification systems across the United States. Historically, similar complaints have been made (e.g. cataloging Asians as “Yellow Peril”).<ref name="Noble"></ref> Opinions differ on solutions to these ethical dilemmas. Some argue that sustaining a goal of neutrality is unrealistic and even harmful, and some claim that rather than only addressing the problematic classifications themselves, information science should focus on educating librarians to expect and decipher inherently non-neutral information.<ref name="Noble"></ref><ref>Drabinski, Emily. “Teaching the Radical Catalog.” <i>Radical Cataloging: Essays at the Front</i>, edited by K.R. Roberto, McFarland & Co., 2008, pp. 198-205</ref> |

| − | == | + | == References == |

<references/> | <references/> | ||

== References == | == References == | ||

* Drabinski, Emily. “Teaching the Radical Catalog.” <i>Radical Cataloging: Essays at the Front</i>, edited by K.R. Roberto, McFarland & Co., 2008, pp. 198-205. | * Drabinski, Emily. “Teaching the Radical Catalog.” <i>Radical Cataloging: Essays at the Front</i>, edited by K.R. Roberto, McFarland & Co., 2008, pp. 198-205. | ||

| − | |||

* Kim, Bohyun. “Moving Forward with Digital Disruption: What Big Data, IoT, Synthetic Biology, AI, Blockchain, and Platform Businesses Mean to Libraries.” <i>Library Technology Reports</i>, vol. 56, no. 2, 2020, doi:10.5860/ltr.56n2. | * Kim, Bohyun. “Moving Forward with Digital Disruption: What Big Data, IoT, Synthetic Biology, AI, Blockchain, and Platform Businesses Mean to Libraries.” <i>Library Technology Reports</i>, vol. 56, no. 2, 2020, doi:10.5860/ltr.56n2. | ||

* Noble, Safiya Umoja. <i>Algorithms of Oppression</i>. E-book, New York UP, 2018. | * Noble, Safiya Umoja. <i>Algorithms of Oppression</i>. E-book, New York UP, 2018. | ||

* Prindle, Sarah and Amber Loos. “Information Ethics and Academic Libraries: Data Privacy in the Era of Big Data.” <i>Journal of Information Ethics</i>, vol. 26, no. 2, Fall 2017, pp. 22-33. | * Prindle, Sarah and Amber Loos. “Information Ethics and Academic Libraries: Data Privacy in the Era of Big Data.” <i>Journal of Information Ethics</i>, vol. 26, no. 2, Fall 2017, pp. 22-33. | ||

* “Professional Ethics.” <i>American Library Association</i>, www.ala.org/tools/ethics. | * “Professional Ethics.” <i>American Library Association</i>, www.ala.org/tools/ethics. | ||

Revision as of 14:48, 26 March 2021

Libraries, as a branch of information science, are being affected by changes in the information landscape.[1] Libraries are concerned with the research, curation, and dispensation of information. In recent years, the world has seen the emergence of Big Data and evolving technology. Ethical dilemmas arise as the traditional card catalog system is eschewed in favor of more technology-driven software, such as the Integrated Library System. Additionally, Big Data and the Internet of Things (IOT) are introducing unique questions about patron privacy and information protection in libraries. Lastly, libraries face the ethical implications of information classification and cataloging processes.

History

Through information technology advancement, libraries have experienced diverse effects that are increasing dependencies on modern tools. Prior to the 1960s, much of the information handling in libraries was manual, hands-on, and self-contained; however, with the introduction of the Integrated Library System (ILS), this began to change.[2] While ILSes are an organizational construct, they commonly consist of database storage and other software features.[3] For example, a program like Sierra that allows library employees to search for a patron’s account and view all materials they currently have borrowed is a feature of the ILS.

Big Data and Library Ethics

As libraries collect and dispense a wider range of data, there is more discussion about the role and responsibility of libraries in relation to Big Data. Academic libraries specifically may be storing information such as full names, social security numbers, and demographics.[2] In software, completely ruling out data leaks is not possible, so inherent risks exist as libraries of any type use these systems and store sensitive information. The question has been posed, is it in violation of the aforementioned Code of Ethics to retain the information if data leaks are possible at all?[2] Additionally, as libraries add resources like e-book resources or database access to help adapt to changing community needs, they are associating with Big Data companies which some argue presents ethical challenges because Big Data is, at its core, a profit industry. For example, in 2016, it was discovered that a popular e-book company used by libraries was collecting personal information.[2] These decisions and incidents demonstrate the ethics of how patron information is no longer merely handled by librarians, but also the third-party companies they use. The role of libraries in this new landscape is discussed as well. Bohyun Kim, an associate professor at the University of Rhode Island as well as their Chief Technology Officer, proposes that an ethical challenge of libraries in the information technology age is providing a space for people to reconnect with their values and remember the importance of physical interaction, hopefully informing ethical use of non-neutral technology.[1]

Ethical Classification

Libraries also face challenges in ethical classification practices. The Library of Congress Classification (LCC) and the Dewey Decimal Classification (DDC) have both experienced accusations of perpetuating stereotypes or biases. Specifically, the Library of Congress experienced requests for reform over the term “illegal alien” as a search term in the online catalog, and the original version of the Dewey Decimal Classification has been questioned over a large percentage of classification being dedicated to Christianity over other religions.[5] The LCC and DDC are widely used classification systems across the United States. Historically, similar complaints have been made (e.g. cataloging Asians as “Yellow Peril”).[5] Opinions differ on solutions to these ethical dilemmas. Some argue that sustaining a goal of neutrality is unrealistic and even harmful, and some claim that rather than only addressing the problematic classifications themselves, information science should focus on educating librarians to expect and decipher inherently non-neutral information.[5][6]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Kim, Bohyun. “Moving Forward with Digital Disruption: What Big Data, IoT, Synthetic Biology, AI, Blockchain, and Platform Businesses Mean to Libraries.” Library Technology Reports, vol. 56, no. 2, 2020, doi:10.5860/ltr.56n2.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Prindle, Sarah and Amber Loos. “Information Ethics and Academic Libraries: Data Privacy in the Era of Big Data.” Journal of Information Ethics, vol. 26, no. 2, Fall 2017, pp. 22-33.

- ↑ “Integrated”

- ↑ “Professional Ethics”

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Noble, Safiya Umoja. Algorithms of Oppression. E-book, New York UP, 2018.

- ↑ Drabinski, Emily. “Teaching the Radical Catalog.” Radical Cataloging: Essays at the Front, edited by K.R. Roberto, McFarland & Co., 2008, pp. 198-205

References

- Drabinski, Emily. “Teaching the Radical Catalog.” Radical Cataloging: Essays at the Front, edited by K.R. Roberto, McFarland & Co., 2008, pp. 198-205.

- Kim, Bohyun. “Moving Forward with Digital Disruption: What Big Data, IoT, Synthetic Biology, AI, Blockchain, and Platform Businesses Mean to Libraries.” Library Technology Reports, vol. 56, no. 2, 2020, doi:10.5860/ltr.56n2.

- Noble, Safiya Umoja. Algorithms of Oppression. E-book, New York UP, 2018.

- Prindle, Sarah and Amber Loos. “Information Ethics and Academic Libraries: Data Privacy in the Era of Big Data.” Journal of Information Ethics, vol. 26, no. 2, Fall 2017, pp. 22-33.

- “Professional Ethics.” American Library Association, www.ala.org/tools/ethics.