Difference between revisions of "Information Ethics"

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | Currently, the most | + | '''Information Ethics'''has a wide range of definitions. Currently, the most commonly accepted definition of Information Ethics is that of [[Floridi|Luciano Floridi]], in his work "Information Ethics, its Nature and Scope,". He defines it broadly as "an ontocentric, patient-oriented, ecological macroethics." Under this model, any entity that can be viewed as an [[Information Object|information object]] has the potential to affect what he refers to as the [[Infosphere]] through interactions with other information objects. Using this model, he attempts to lay the groundwork in the field of Information Ethics for a "unified approach" to defining policies within it. |

| + | ([[Tops & Categories|Back to index]]) | ||

| + | |||

==Models of Information Ethics== | ==Models of Information Ethics== | ||

Revision as of 01:21, 28 November 2011

Information Ethicshas a wide range of definitions. Currently, the most commonly accepted definition of Information Ethics is that of Luciano Floridi, in his work "Information Ethics, its Nature and Scope,". He defines it broadly as "an ontocentric, patient-oriented, ecological macroethics." Under this model, any entity that can be viewed as an information object has the potential to affect what he refers to as the Infosphere through interactions with other information objects. Using this model, he attempts to lay the groundwork in the field of Information Ethics for a "unified approach" to defining policies within it. (Back to index)

Contents

Models of Information Ethics

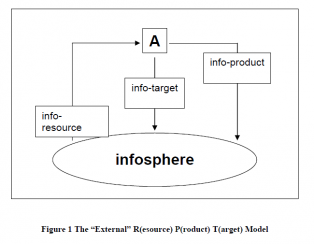

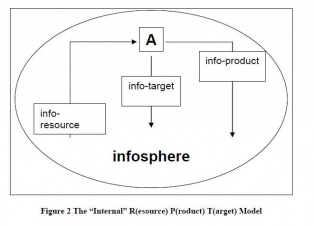

These all fall under Floridi's External and Internal Resource Product Target Models (shortened to ERPT and IRPT).

- Information-as-a-Resource Ethics

Attempts to scope the ethicality of an action based on the agent's knowledge base. Moral responsibility ∝ agent's "degree of information." Floridi defines a basis for this approach as "the triple A:" Availability, Accessibility, and Accuracy. What does X know of Y.

- Information-as-a-Product Ethics

Covers "moral issues arising... in the context of accountability, liability, libel, legislation, testimony, plagiarism, advertising, propaganda, misinformation, etc." Thus the product that is targeted here is the Y that comes from X (X produces Y).

- Information-as-a-Target Ethics

Aiming at acts and items such as hacking, security, vandalism, piracy, intellectual property, open source, freedom of information, expression, censorship, filtering and contents control, the situations under analysis here comes under the form X targets, or engages Y.

Levels of Abstraction

Floridi defines Levels of Abstraction (LoA) in a more basic form than its discrete mathematics form. He interprets them as, in general, a set of interpretations on or of an object. They can be grouped into an interface, or Gradient of Abstraction (GoA). Methods of Abstraction can be derived from levels "at specified gradients."

Moral Agent

Floridi defines a moral agent as "an interactive, autonomous, and adaptable transition system that can perform morally qualifiable actions." He notes that a transition system's "precise definition" is dependent upon the LoA it takes: interactive with the surroundings, autonomous with respect to the environment, and/or adaptable to the environment and various experiences. Morally qualifiable just means good or evil can result from an act (or in the words of Aristotle, the act is either noble or base).

It is this definition that permits Floridi's brand of IE to cover natural and artificial agents, including computer programs (viruses), robots, animals, etc. Everything is placed on a level playing field for judgement under this system.

Applications in the Infosphere

In "Information ethics, its Nature and Scope," Floridi asserts that the infosphere is the information environment. Any alteration or readjustment to the infosphere affects it directly; and on the other hand, any harm done within or to the infosphere itself causes a disarray in a natural system, or entropy. Namely, entropy is defined to represent the destruction or corruption of informational objects. Floridi insists that entropy, or wrong doing, should not be done in any infosphere; it should be prevented and avoided.

Floridi's definition of entropy is an integral aspect to the information environment because it substantiates information objects' rights of 'being', or the "equal rights to exist and develop in a way which is appropriate to its nature." Moreover, this right of 'being' is especially important because morally wrong behavior is the result of a deficiency in information (i.e. entropy destroys information, creating vacuums in which there exist no well-defined policies towards an ethical approach, leading to an increase in morally abject behaviors).

Fundamental Principles

From which responsibilities as moral agents can be derived, Floridi lays out four laws (starting at law 0, in classical computer science form) quoted here:

- 0.) Entropy ought not to be caused in the infosphere (null law)

- 1.) Entropy ought not to be prevented in the infosphere

- 2.) Entropy ought to be removed from the infosphere

- 3.) The flourishing of informational entities as well as of the whole infosphere ought to be promoted by preserving, cultivating and enriching their properties and interactions.

Uniqueness of Computer Ethics

Is computer ethics a unique field? Its singularity has been challenged since its advent. Traditionalists argue that computer ethics is just an extension of basic ethical concepts that are fitted to a new medium while proponents argue that computers and information technology bring about a whole new set of ethical dilemmas that must be filled and, if not, we run the risk of creating policy vacuums.

Traditionalist view

The traditionalist does not support the uniqueness of computer or cyber ethics. Their main argument is that a crime is merely a crime and that there are no unique moral issues specific to the use of computers. For example theft would be considered theft whether it took place in someone’s home or through someone’s online banking.

Computer Ethics is Unique Theory (CEIU)

This theory is discussed in Herman Tavani's article The uniqueness debate in computer ethics: What exactly is at issue, and why does it matter?. This is the theory that the twists on ethical dilemmas make in the online environment are not trivial and are unique because they are in a different medium. [1]

In the CEIU thesis, in order for one to make an accurate judgment on a particular action, a person must have “adopted an understanding of what basic reality is about” [1]. and with this understanding of reality assess whether the particular action falls in congruence with said reality. These advocators argue that traditionalists don’t fully understand both the nature of computer ethics as well as the spectrum.

Cyberstalking Example

A principal example that many proponents use to differentiate the field of computer ethics from its real world counterparts is the issue of stalking. In a real world situation stalking is a criminal offense and is seen as a distinctive form of harassment in the eyes of the law. In the physical world a stalker is trailing and tracking their person of interest. The person can become privy to their stalkers actions and report them to the authorities. Stalking in a virtual environment is a very different situation. A stalker can potentially go unnoticed for an indefinite amount of time. The stalker can use online search engines and social networks to find out information about a person without even leaving the comfort of their own home. Currently policies do not exist that specifically address legality of this situation, and unless any direct contact from the stalker is made that could be construed as harassment, there is currently nothing that can be done to prevent this.

References

- ↑ Tavani, Herman. "The uniqueness debate in computer ethics: What exactly is at issue, and why does it matter?". Ethics and Information Technology 4:37-54, 2002.

Additional Readings

1. Computer and Information Ethics