Difference between revisions of "Project Green Light"

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

==Methodology== | ==Methodology== | ||

| − | As a public-private partnership, Project Green Light is a paid service that Detroit businesses, residential complexes, schools, churches, and other institutions opt into willingly. Each participant of Project Green Light pays for installation of cameras, signage, decals and green lights to identify that they are part of the project. The cost of these materials for businesses ranges from $4,000 to $6,000.<ref> Project Green Light Detroit. City of Detroit. (n.d.). Retrieved January 25, 2023, from https://detroitmi.gov/departments/police-department/project-green-light-detroit</ref> The cameras which monitor buildings are strategically placed to capture license plates and faces of individuals at any given location. This footage from cameras is available 24/7 and is monitored and virtually patrolled in real-time by members of the police, analysts, and volunteers. Much of this work is done at Detroit's Real-Time Crime Center, also launched in 2016 costing the city an initial $8 million with an additional $4 million for expansion in 2019.<ref>Detroit real-time crime center. Atlas of Surveillance. (n.d.). Retrieved January 27, 2023, from https://atlasofsurveillance.org/real-time-crime-centers/detroit-real-time-crime-center</ref> | + | As a public-private partnership, Project Green Light is a paid service that Detroit businesses, residential complexes, schools, churches, and other institutions opt into willingly. Each participant of Project Green Light pays for installation of cameras, signage, decals and green lights to identify that they are part of the project. The cost of these materials for businesses ranges from $4,000 to $6,000.<ref> Project Green Light Detroit. City of Detroit. (n.d.). Retrieved January 25, 2023, from https://detroitmi.gov/departments/police-department/project-green-light-detroit</ref> The cameras which monitor buildings are strategically placed to capture license plates and faces of individuals at any given location. This footage from cameras is available 24/7 and is monitored and virtually patrolled in real-time by members of the police, analysts, and volunteers. Much of this work is done at Detroit's Real-Time Crime Center (RTCC), also launched in 2016 costing the city an initial $8 million with an additional $4 million for expansion in 2019.<ref>Detroit real-time crime center. Atlas of Surveillance. (n.d.). Retrieved January 27, 2023, from https://atlasofsurveillance.org/real-time-crime-centers/detroit-real-time-crime-center</ref> The RTCC prioritizes Project Green Light affiliates over non-affiliates and works with such government agencies as the FBI, the Department of Homeland Security, and private partners including DTE and Rock Financial. |

==Concerns== | ==Concerns== | ||

Revision as of 22:07, 27 January 2023

Project Green Light is a city-wide police surveillance system in Detroit, Michigan. The first public-private-community partnership of its kind,[1] Project Green Light Detroit utilizes real-time police monitoring using high-resolution cameras (1080p) whose images can be linked to the state of Michigan's facial recognition database, SNAP. The Project's aim is to deter and reduce city crime and is used in the pursuit of criminals.

Contents

History

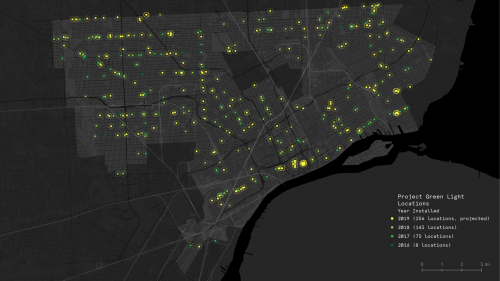

Launched January 1, 2016 with support from Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan, eight city gas station businesses were recruited with the assurance from the Detroit Police Department that the flashing green lights and cameras to be installed at each location would help identify criminal suspects in any future crimes, as well as helping lower crime altogether.[2] With continued governmental and state support, Project Green Light expanded with the justification that Detroit Police Department data showed a decrease in “criminal activity” at the original eight locations. Since its inception, the number of institutions who pay for Project Green Light infrastructure has expanded to over 700 locations as of January, 2021.

In 2017, the city of Detroit contracted an agreement with DataWorks Plus and began to implement their facial recognition software, FacePlus into Project Green Light technologies.[3] FacePlus can automatically search any face that enters the camera's field of vision and may assess them against a statewide database.

According to news sources in June 2020,[4] Project Green Light has allegedly been used on crowds in Black Lives Matter protests using supplemental facial recognition technology to identify protestors who did not adhere to social distancing protocols, a violation which carries up to a $1,000 fine. Project Green Light images have also been allegedly used to help police identify and locate further #BLM protestors whose immigration status was under question.[5]

Methodology

As a public-private partnership, Project Green Light is a paid service that Detroit businesses, residential complexes, schools, churches, and other institutions opt into willingly. Each participant of Project Green Light pays for installation of cameras, signage, decals and green lights to identify that they are part of the project. The cost of these materials for businesses ranges from $4,000 to $6,000.[6] The cameras which monitor buildings are strategically placed to capture license plates and faces of individuals at any given location. This footage from cameras is available 24/7 and is monitored and virtually patrolled in real-time by members of the police, analysts, and volunteers. Much of this work is done at Detroit's Real-Time Crime Center (RTCC), also launched in 2016 costing the city an initial $8 million with an additional $4 million for expansion in 2019.[7] The RTCC prioritizes Project Green Light affiliates over non-affiliates and works with such government agencies as the FBI, the Department of Homeland Security, and private partners including DTE and Rock Financial.

Concerns

Civil Liberties

In the state of Michigan since 1999, every person taking a state ID has had their image added to a facial recognition database (SNAP). These images are used to profile those seen through Project Green Light video footage, and city activists have expressed discontent with this practice. Additionally, the use of real-time tracking, especially on mobile devices has been challenged. Opponents of the project have raised objections that the technologies and methods in place violate the first, fourth, and fourteenth amendments.

Health and Well-Being

The effects of mass surveillance on a population include fear, mistrust, paranoia, anxiety, and erosion of identity. The feeling of being watched, even at one's residence or religious institution can stifle authentic expression, deteriorate communal relationships, and promote loss of faith in government.

Surveillance of Black Bodies

Facial recognition is proven to be less effective for women and darker skinned individuals.[8] Inaccuracies run the risk of negative consequences for innocent civilians who are misidentified. Sociologist Ruha Benjamin has described contemporary biometric surveillance as a form of technologies used to support racist policies and practices through the tracking and control of Black people throughout American history. Surveillance of Black bodies has a long history can be traced back to slavery. The “lantern-laws” of 18th-century required Black people to illuminate themselves when passing white people in the street. The use of facial recognition on racial justice protestors recalls the COINTELPRO surveillance of Black activists and community organizers in the 1960s. Video surveillance in Detroit, a city with an 80% Black population has been theorized as a continuing legacy of oppression. Introducing the use of this technology through Project Green Light makes this massive facial recognition experiment the first of its kind in on a concentration of Black individuals.

Security vs Safety

The idea that public security measures such as surveillance equates to public safety has led local governments to make problematic decisions that facilitate an outcome that many believe to be ineffective and unsafe for community members. Such policies, such as predictive policing, may disproportionately affect marginalized peoples (undocumented, formerly incarcerated, unhoused, poor, etc.) and minority (black, latinx, etc) populations.[9]

See Also

References

- ↑ Project Green Light Detroit. City of Detroit. (n.d.). Retrieved January 25, 2023, from https://detroitmi.gov/departments/police-department/project-green-light-detroit

- ↑ Campbell, Eric T.; Howell, Shea; House, Gloria; & Petty, Tawana (eds.). (2019, August). Special Issue: Detroiters want to be seen, not watched. Riverwise. The Riverwise Collective.

- ↑ A critical summary of Detroit’s Project Green Light and its greater context. (n.d.). Retrieved January 26, 2023, from https://detroitcommunitytech.org/system/tdf/librarypdfs/DCTP_PGL_Report.pdf?file=1%26type=node%26id=77%26force=

- ↑ WXYZ-TV Detroit | Channel 7. (2020). Future of Facial Recognition Technology. Retrieved January 25, 2023, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h-3_cTPqKI4.

- ↑ Race, policing, and Detroit's Project Green Light. UM ESC. (2020, June 25). Retrieved January 25, 2023, from https://esc.umich.edu/project-green-light/

- ↑ Project Green Light Detroit. City of Detroit. (n.d.). Retrieved January 25, 2023, from https://detroitmi.gov/departments/police-department/project-green-light-detroit

- ↑ Detroit real-time crime center. Atlas of Surveillance. (n.d.). Retrieved January 27, 2023, from https://atlasofsurveillance.org/real-time-crime-centers/detroit-real-time-crime-center

- ↑ Buolamwini, J., & Gebru, T. (2018, January 21). Gender shades: Intersectional accuracy disparities in commercial gender classification. PMLR. Retrieved January 27, 2023, from http://proceedings.mlr.press/v81/buolamwini18a.html

- ↑ Shapiro, Aaron. Reform predictive policing. Nature. January 25, 2017, Vol. 541, pp. 458-460.