Robocalls

Robocalls are calls dialed using an automated software that contain a prerecorded message.[1] They can be used to deliver informational messages such as in robocalls that are from health care providers, debt collectors, charities, political campaigns, or otherwise any other purely informational message.[2] Robocalls can also be used for telemarketing purposes, with permission of the recipient.[3]

There are many ethical concerns revolving around robocalls, mainly due to the potential for scammers to impersonate companies, charities, or government entities. Roughly 59.4 million Americans lost money due to scam robocalls in 2021 alone.[4] New legislation and technology has emerged to combat robocalls, and individuals have also taken outside action.

History

Dinner Time Telemarketing

Telemarketing calls during the late 80s and 90s consisted of real people calling to try and sell a product or service.[5] Dialers at this time were manually operated and required a person on the other end to play a prerecorded message.[6] At this time making robocalls was very expensive.[7]

Tony Inocentes

One alleged origin of modern robocalling is that it was invented by Tony Inocentes. In January 1983, Tony Inocentes used robocall technology he designed to announce his candidacy for the 57th Assembly District in California. In 1989, he created robocall software for debt collecting agencies. In 2001, he also invented political robopolling.[8]

Emergence of Mass Robocalls

In 2015, the FCC released a declaratory ruling defining autodialers as “equipment used to make a call… [that] is capable of storing or generating sequential or randomized numbers at the time of the call”. The order limited the use of autodialers, under this definition, to make robocalls.[9] After the order was passed, robocall companies moved to create call centers and hire more employees who would dial numbers individually while still having a prerecorded message play upon being answered. The order succeeded in reducing the number of robocalls being made, but was later undermined in 2018 by the DC Circuit Court.[10] The DC Circuit Court found that the definition stated in the 2015 order was arbitrary since it meant that many devices, including smartphones, could be considered autodialers.[11] After the DC Circuit Court ruling, robocalls significantly increased in frequency. From the beginning of 2018 to the end of that year, robocalls had increased by 80% totaling 48 billion robocalls.[10]

Other rulings also impacted the rise in robocalls. The Supreme Court Ruling in Spokeo Inc v. Robins found that annoyance is not enough of a justification to sue a telemarketer, and the plaintiff must be injured. State courts also tend to follow that rule. As a result, it is very difficult for robocallers to face criminal prosecution.[12]

Ethical Implications

Scams

Robocalls are the top consumer complaint reported annually to the FCC.[13] In 2022, 68.4M Americans (26%) reported losing money from phone scams with robocalls scamming 61.1% of those individuals. Many of the individuals harmed by robocall scams are elderly and of hispanic background. [14] Scammers will prey on the insecurities of these demographics. Latino victims may be the target of immigration scams.[15] Seniors are targeted more because they usually have landlines (which are more susceptible to robocalls because they can’t support the new technology created to stop receiving them) and they answer unknown numbers more often.[16][17] The scammers purchase phone numbers from lead brokers and pay small phone service providers to place their calls.[18] Robocall scams often impersonate companies, charities, or government entities in an attempt to receive an individual’s personal information or money.

Robocall scams mainly originate from India, Mexico, United States, Guatemala, and Costa Rica. Robocalls from Mexico, Guatemala, and Costa Rica involve travel scams and illiegal marketing. In the US, robocalls originate from mainly five states: California, Florida, Colorado, New York, and Tennessee. Scam robocalls from California are mainly get-rich-quick schemes, home solar energy scams, and misleading weight loss telemarketing. Robocalls made in Florida include credit card scams, spoofing, and medical alert scams. In Colorado, New York, and Tennessee, robocall scams are mainly get-rich-quick schemes. Of those that originate in India, the scam will mainly have to do with IRS, social security, or tech support.[19] Call centers in India can range from 10-15 to 400-500 employees.[20]

An investigation into, Accostings, an Indian tech support scam company, by journalists Alex Goldman and PJ Vogt of Gimlet Media, found that Indian tech support scams began with a robocall to confuse the victims into calling back. Upon calling back, victims would be connected with a scammer impersonating a tech consultant who would then convince the victims to give them remote access to their computer. Using the computer’s terminal, the scammer will make it appear as though the computer has a virus and then attempt to solicit payment from the victim in order to remove the “virus”. The company’s reach extends across the world with money processing centers in the US and UK.[21]

Spoofing

Spoofing technology has made impersonation easier for scammers by allowing changes to be made to caller IDs. [22] One form of spoofing is called neighbor spoofing in which scammers will mask a caller ID with a local number to impersonate a neighbor or nearby company. Spoofed robocalls will use prerecorded scam scripts to confuse individuals into giving up personal information or money.[23]

One-ring calls

Other forms of robocall scams are ‘one-ring’ scams. In these scams, robocalls are used to call several individuals for only ‘one-ring’, with the goal of having a potential victim call the number back and be charged connecting and per-minute fees. The robocalls may be spoofed to impersonate a U.S. based call while actually being made internationally.[24]

Privacy

Robocallers can spoof phone numbers based on which location the recipient is in. Although the methods by which robocallers acquire location information remains unclear, there are theories that possibly explain the process of acquiring an individual’s location data. The first theory explains that the source of the data originates from telecom companies. Telecommunication companies sell real-time location data to location aggregators who act as middlemen. Location aggregators proceed to sell that data to other people or companies, which could possibly include robocallers. According to location aggregator companies, data is not being sold to robocallers and that consumer consent is required before data can be sold to another company, whoever many individuals still report being tracked without consent. Another theory is that the source of the data is coming from phone apps. Phone apps can collect varying amounts of user data, including phone numbers. The apps can send the data to advertising companies or other locations on the internet, which could possibly include robocallers. It is also possible that any vulnerability in the app code could give robocallers an opportunity to collect user information as well.[10]

Employee Exploitation

In an investigation by Gimlet Media, it was found that most of the individuals working for the Indian robocall scam company, Accostings, were young and likely working their first job. 1.5 million engineers graduate from Indian educational institutions every year, but fewer than 20% get jobs in their field, leaving many to work for scam companies, whether they are aware or not.[25]Many of the workers come from poorer cities, and are recruited and exploited by being offered legitimate work only to then be working for a scam company. The company has a high turnover rate due to withholding pay from the employees. Higher ups could threaten employees who spoke out against the company with arrest.[21]

Robocall Legislation

Telephone Consumer Protection Act and Telemarketing Sales Rule

Both the Telephone Consumer Protection Act and Telemarketing Sales Rule regulate telemarketing calls, with variations in what entity enforces the rules outlined in these two documents.

In 1991, Congress passed the Telephone Consumer Protection Act of 1991 (TCPA), which restricted the use of calls with automated dialing systems and prerecorded messages without consent. Calls exempt from the restrictions are those that are not made for commercial purposes, and commercial calls so long as they do not affect the party’s privacy or include unsolicited advertisements. The TCPA entrusted the delegation of rules to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC).[26] After being adopted in 1992, one such rule the FCC made was that companies keep their own specific do-not-call registries.

FCC rules regarding the TCPA were revised in 2012 to require telemarketers: “(1) to obtain prior express written consent from consumers before robocalling them, (2) to no longer use an "established business relationship" to avoid getting consent from consumers when their home phones, and (3) to provide an automated, interactive "opt-out" mechanism during each robocall so consumers can immediately tell the telemarketer to stop calling.” (13) The TCPA was further revised on July 2015 when the FCC released the TCPA Declaratory Ruling and Order which allows telephone service providers to offer robocall blocking to customers."[27]

The Telemarketing Sales Rule (TSR), effective on September 1, 2009, is enforced by the Federal Trades Commission (FTC). The TSR prohibits telemarketing robocalls unless the recipient has given written consent. The TSR also states that any robocall must:"1) allow the telephone to ring for at least 15 seconds or four rings before an unanswered call is disconnected; 2) begin the prerecorded message within two seconds of a completed greeting by the consumer who answers; 3) disclose at the outset of the call that the recipient may ask to be placed on the company's do-not-call list at any time during the message; 4) in cases where the call is answered by a person, make an automated interactive voice and/or keypress-activated opt-out mechanism available during the message that adds the phone number to the company's do-not-call list and then immediately ends the call; and 5) in cases where the call is answered by an answering machine or voicemail, provide a toll-free number that allows the person called to be connected to an automated interactive voice and/or keypress-activated opt-out mechanism anytime after the message is received."[28]

National Do-Not-Call Registry

Growing use of auto dialers for telemarketing purposes after 1992 prompted the Federal Trades Commission to establish a national Do-Not-Call Registry in 2003 to allow for better compliance of TCPA guidelines. The registry consists of a list of phone numbers, maintained by the federal government, whose owners have expressed they do not want to receive telemarketing calls. The list does not cover the exemptions listed in the TCPA.[29] The Do-Not-Call Improvement Act of 2007 revised some of the Registry’s rules to remove the 5-year limit on registered numbers. Any phone numbers on the Registry now remain there permanently unless the owner of the number requests removal or the number is invalid.[30]

TRACED Act

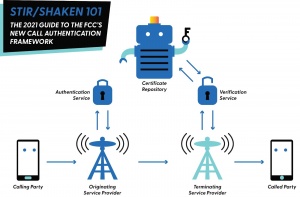

In 2019, Congress passed the Pallone-Thune Telephone Robocall Abuse Criminal Enforcement and Deterrence (TRACED) Act which gave the FCC new ways to combat robocalls.[31] The FCC implemented the STIR/SHAKEN framework, which allows caller IDs to be verified for calls carried over Internet Protocol (IP) networks. The Secure Telephone Identity Governance Authority (STI-GA) issues private keys on digital certificates to carriers. These keys can be used to digitally sign off on calls made over the Internet.[32]

“1. When a call is initiated, a SIP INVITE is received by the originating service provider.2. The originating service provider verifies the call source and number to determine how to confirm validity.

- Full Attestation (A) — The service provider authenticates the calling party AND confirms they are authorized to use this number. An example would be a registered subscriber.

- Partial Attestation (B) — The service provider verifies the call origination but cannot confirm that the call source is authorized to use the calling number. An example would be a calling number from behind an enterprise PBX.

- Gateway Attestation (C) — The service provider authenticates the call’s origin but cannot verify the source. An example would be a call received from an international gateway.

3. The originating service provider will now create a SIP Identity header that contains information on the calling number, called number, attestation level, and call origination, along with the certificate.

4. The SIP INVITE with the SIP Identity header with the certificate is sent to the destination service provider.

5. The destination service provider verifies the identity of the header and certificate.”[33]

If a call cannot be verified, the provider may block it or the recipient may be warned with a ‘Scam Likely’ on the caller ID screen.[32]

Outside Action

Despite FCC and FTC legislation and enforcement, US consumers received 50.3 billion robocalls in 2022.[34] Some individuals have started using different methods to stop unwanted robocalls and trick scammers.

Scambaiting

Scambaiters are vigilantes who are aware they are being scammed but pretend to be falling for the scam to waste the time and money of the perpetrator.[35] Some scambaiters may attempt to expose the scammers and possibly get them arrested.[36]

Scambaiting has become a popular topic online. One popular scambaiter is Jim Browning, who uploads videos to his YouTube channel documenting scam tactics, and occasionally is able to intervene and stop a potential victim from being scammed.[37] Jim Browning has also been able to get access to scammers’ computers and identify scammers by using CCTV footage of a scam call center. He shares this information with authorities.[38]

Many believe there are ethical implications with scambaiters causing more harm than good. Baiters may label innocent people as scammers and release information about them threatening their privacy and safety. Some scambaiters may also steal money from a scammer’s bank account. Scambaiting has also been criticized as being racist since many of the baiters’ targets are people of color from developing countries.[39] Scambaiters are also known to humiliate scammers by collecting “trophies” which can be fairly harmless to more detrimental. Some “trophies” involve having the scammer get a tattoo which could be dangerous if the scammer is from West Africa where there are high rates of vaccine transmission. Another trophy involves having scammers travel several miles away from home only to leave them stranded with no way of returning home.[40]

References

- ↑ Kaspersky. (2022, February 9). What are robocalls, and how can you stop them? www.kaspersky.com. Retrieved January 21, 2023, from https://www.kaspersky.com/resource-center/definitions/what-are-robocalls

- ↑ Hebert, A., Hernandez, A., Perkins, R., & Puig, A. (2022, June 8). Robocalls. Federal Trade Commission Consumer Advice. Retrieved January 21, 2023, from https://consumer.ftc.gov/articles/robocalls

- ↑ Cahill, E. (2022, June 29). What is a Robocall? Experian. Retrieved January 21, 2023, from https://www.experian.com/blogs/ask-experian/what-is-a-robocall/

- ↑ Leonhardt, M. (2021, June 29). Americans lost $29.8 billion to phone scams alone over the past year. CNBC. Retrieved January 21, 2023, from https://www.cnbc.com/2021/06/29/americans-lost-billions-of-dollars-to-phone-scams-over-the-past-year.html

- ↑ https://www.fcc.gov/news-events/podcast/robocalls

- ↑ Phone does its own dialing when lever pushed Popular Mechanics, (1942, February). p. 70.

- ↑ Ramirez, X. (2022, January 21). Robocalls & how they emerged: A complete history. Firewall. Retrieved January 21, 2023, from https://www.tryfirewall.com/blog/robocalls

- ↑ Gwaltney, H. (2019, July 2). Robocalls – everything you need to know. GTB. Retrieved January 21, 2023, from https://gtb.net/why-gtb/blog/robocalls-%E2%80%93-everything-you-need-know#:~:text=The%20man%20behind%20robocalls%20is,by%20debt%20collectors%20at%20large.

- ↑ FCC. (2015). Rules and Regulations Implementing the Telephone Consumer Protection Act of 1991. [FCC-15-72]. https://www.fcc.gov/document/tcpa-omnibus-declaratory-ruling-and-order

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Goldman, A. Vogt, PJ. (Host). (2019, January 31). Robocalls: Bang Bang (No. 135) [Audio podcast episode]. In Reply All. Gimlet. https://gimletmedia.com/shows/reply-all/awhk76

- ↑ Ranlett, K., & Parasharami, A. A. (2018, March 19). DC circuit issues long-awaited TCPA decision and invalidates FCC's 2015 autodialer and reassigned-number rules. Class Defense Blog. Retrieved February 9, 2023, from https://www.classdefenseblog.com/2018/03/dc-circuit-issues-long-awaited-tcpa-decision-and-invalidates-fccs-2015-autodialer-and-reassigned-number-rules/

- ↑ Hickey, W. (2021, March 3). The annoyance engine: Spam robocalls became profitable scams by exploiting the phone system, but you can stop them. Business Insider. Retrieved February 10, 2023, from https://www.businessinsider.com/why-so-many-spam-robocalls-how-to-stop-them-2021-3

- ↑ Traced act implementation. Federal Communications Commission. (2021, November 19). Retrieved January 21, 2023, from https://www.fcc.gov/TRACEDAct

- ↑ Truecaller. (2022, May 24). Truecaller insights 2022 U.S. Spam & Scam Report. Truecaller Blog. Retrieved January 21, 2023, from https://www.truecaller.com/blog/insights/truecaller-insights-2022-us-spam-scam-report

- ↑ Gómez, A. (2022, December 6). Latinos in the U.S more likely to be targeted by scams during the holiday season. Latinos in the U.S More Likely to be Targeted by Scams During the Holiday Season. Retrieved February 8, 2023, from https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/latinos-in-the-us-more-likely-to-be-targeted-by-scams-during-the-holiday-season-301695329.html

- ↑ Hopkins, S. (2022, June 29). Combat Robocalls and scams targeting seniors. Your AAA Network. Retrieved February 8, 2023, from https://magazine.northeast.aaa.com/daily/money/retirement/scams-targeting-seniors/#:~:text=Robocalls%20are%20typically%20scams%20targeting,the%20world%20of%20internet%20scams

- ↑ Brodkin, J. (2021, July 2). US hits anti-robocall milestone but annoying calls won't stop any time soon. Ars Technica. Retrieved February 8, 2023, from https://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2021/07/us-hits-anti-robocall-milestone-but-annoying-calls-wont-stop-any-time-soon/

- ↑ Bethany Mclean, I. by E. S. (2020, April 1). How do robocalls work? understanding robocall scams. AARP. Retrieved January 21, 2023, from https://www.aarp.org/money/scams-fraud/info-2020/how-do-robocalls-work.html

- ↑ Purdue, M. (2019, July 9). This is where robocalls are coming from (and where they are targeting). USA Today. Retrieved February 8, 2023, from https://www.usatoday.com/story/tech/2019/07/09/where-robocalls-come-from-and-where-they-target/1660503001/

- ↑ Goldman, A. Vogt, PJ. (Host). (2017, August 17). Long Distance, Part II (No. 103) [Audio podcast episode]. In Reply All. Gimlet. https://gimletmedia.com/shows/reply-all/76h5gl/103-long-distance-part-ii

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Goldman, A. Vogt, PJ. (Host). (2017, August 17). Long Distance (No. 102) [Audio podcast episode]. In Reply All. Gimlet. https://gimletmedia.com/shows/reply-all/6nh3wk

- ↑ Stouffer, C. (2022, September 15). What is a Robocall? A definition + how to avoid robocalls. Norton. Retrieved January 21, 2023, from https://us.norton.com/blog/online-scams/what-is-a-robocall#

- ↑ Caller ID spoofing. Federal Communications Commission. (2022, March 7). Retrieved January 21, 2023, from https://www.fcc.gov/spoofing

- ↑ 'One Ring' phone scam. Federal Communications Commission. (2020, February 28). Retrieved January 21, 2023, from https://www.fcc.gov/consumers/guides/one-ring-phone-scam

- ↑ Bhattacharjee, Y. (2021, January 27). Who's making all those scam calls? The New York Times. Retrieved February 9, 2023, from https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/27/magazine/scam-call-centers.html

- ↑ Senate - Commerce, Science, and Transportation. (1991). Telephone Consumer Protection Act of 1991 [S.1462 — 102nd Congress]. https://www.congress.gov/bill/102nd-congress/senate-bill/1462/text.

- ↑ FCC. (Monday, June 11, 2012). Telephone Consumer Protection Act of 1991 [77 FR 34233-34249]. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2012-06-11/pdf/2012-13862.pdf

- ↑ 15 U.S.C. 6101-6108. (August 10, 2010). Telemarketing Sales Rule [16 CFR Part 310]. https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-16/chapter-I/subchapter-C/part-310

- ↑ FCC. (2003). Rules and Regulations Implementing the Telephone Consumer Protection Act of 1991. [FCC-03-153]. https://www.fcc.gov/document/rules-and-regulations-implementing-telephone-consumer-protection-act-22/attachment-0

- ↑ House - Energy and Commerce | Senate - Commerce, Science, and Transportation. (2008). Do-Not-Call Improvement Act of 2007. [H.R.3541 — 110th Congress]. https://www.congress.gov/bill/110th-congress/house-bill/3541

- ↑ Senate - Commerce, Science, and Transportation | House - Energy and Commerce. (2019). Pallone-Thune Telephone Robocall Abuse Criminal Enforcement and Deterrence Act. [S.151 — 116th Congress]. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senate-bill/151#:~:text=151%20%2D%20116th%20Congress%20(2019%2D,Congress.gov%20%7C%20Library%20of%20Congress

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 STIR/SHAKEN: Everything You Need to Know. Plivo. (2022, July 1). Retrieved January 21, 2023, from https://www.plivo.com/blog/voice-calls-stir-shaken/?kw=&cpn=17867267906&utm_campaign_type=search&utm_term=&utm_campaign=CY22-Q3-GoogleSearch-Americas-US%2FCanada-SEM-WebsiteTraffic-DSA-HypeBlog&utm_source=google&utm_medium=cpc&hsa_acc=2092392810&hsa_cam=17867267906&hsa_grp=138933387549&hsa_ad=612851501458&hsa_src=g&hsa_tgt=dsa-1699600679256&hsa_kw=&hsa_mt=&hsa_net=adwords&hsa_ver=3&gclid=Cj0KCQiAlKmeBhCkARIsAHy7WVvWdHI-zHAJyYMq3bqU-nGQZYkN7ErKkS17dRz_hgogbxpkF9-r-uoaAhI2EALw_wcB

- ↑ Stir/shaken: An overview of what it is and how it works. REDCOM. (2020, January 15). Retrieved January 21, 2023, from https://www.redcom.com/stir-shaken-overview/

- ↑ Notaney, R. (2023, January 5). Robocalls top 50.3 billion in 2022, matching 2021 call volumes despite enforcement efforts. Robocalls Top 50.3 Billion in 2022, Matching 2021 Call Volumes Despite Enforcement Efforts. Retrieved February 8, 2023, from https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/robocalls-top-50-3-billion-in-2022--matching-2021-call-volumes-despite-enforcement-efforts-301714297.html#:~:text=IRVINE%2C%20Calif.%2C%20Jan.,government%20regulators%20and%20state%20officials

- ↑ Dictionary.com. (n.d.). Scambaiting. In Dictionary.com dictionary. Retrieved February 8, 2023, from https://www.dictionary.com/browse/scambaiting#:~:text=%2F%20(%CB%88sk%C3%A6m%CB%8Cbe%C9%AAt%C9%AA%C5%8B)%20%2F,the%20time%20of%20the%20perpetrators

- ↑ Vernon, H. (2021, February 10). I'm an online vigilante who hacks scammers. VICE. Retrieved February 8, 2023, from https://www.vice.com/en/article/93w8pe/youtuber-exposing-scams-scambaiter

- ↑ O'Brien, J. (2021, October 28). Scamming the scammers: How everyday people are fighting back against phone fraudsters. WPEC. Retrieved February 8, 2023, from https://cbs12.com/news/local/scamming-the-scammers-how-everyday-people-are-fighting-back-against-phone-fraudsters

- ↑ Tait, A. (2021, October 3). Who scams the scammers? meet the scambaiters. The Guardian. Retrieved February 8, 2023, from https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2021/oct/03/who-scams-the-scammers-meet-the-amateur-scambaiters-taking-on-the-crooks

- ↑ Farooghian, S. (2020, October 13). Scambaiting's effect. Medium. Retrieved February 8, 2023, from https://medium.com/scambatings-effect/scambaitings-effect-51908cf0c19e

- ↑ Whittaker, J. M., & Mark, B. (2021, June 23). 'scambaiting': Why the vigilantes fighting online fraudsters may do more harm than good. The Conversation. Retrieved February 8, 2023, from https://theconversation.com/scambaiting-why-the-vigilantes-fighting-online-fraudsters-may-do-more-harm-than-good-163038