Electronics Right to Repair

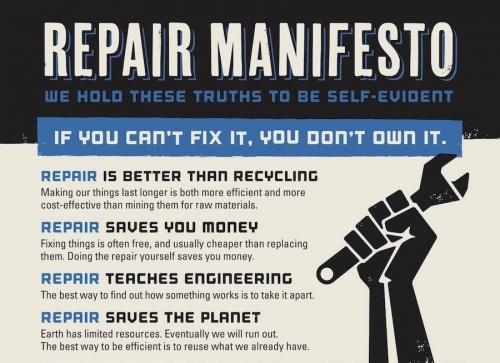

Electronics Right to Repair is a movement that aims to provide consumers approachable and economical means to repair their electronic devices. While consumers currently have the right to repair their own devices, and there are many independent (not manufacturer-authorized) repair shops across the U.S., consumers and independent repair technicians often struggle to successfully perform repairs due to their inability to access replacement parts, service manuals, and diagnostics tools. In addition, some manufacturers, such as Apple and Samsung, impose software barriers that may limit the functionality of devices with repaired or replaced hardware components[2].

The benefits of Right to Repair generally include increased competition in the repair market and the reduction of electronic waste. As a result, accessibility and affordability of repair services would improve, and the total cost of owning and utilizing electronic devices would decrease[3].

However, the adoption of Right to Repair — especially legislative efforts that mandate its adoption — has faced opposition from major lobbying groups representing consumer electronics manufacturers. They often argue that providing parts, tools, and diagnostic software compromises security features of consumer electronics devices, hence granting third parties access to such information may put their users and their users' personal data at risk[4]. Manufacturers may also claim that "unauthorized" repairs done by independent repair providers may violate copyright laws and their rights to their proprietary software and hardware components[5].

Contents

Current challenges to repairing electronic devices

In 2019, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) authored a report on electronics device manufacturers' restrictions of repair, titled Nixing the Fix. In this report, the FTC uncovers several issues regarding the accessibility of repair, including[6]:

- Applying excessive amounts of adhesives, which makes it difficult to disassemble devices.

- Limiting availability of parts, manuals, and diagnostics software to the manufacturers themselves and their global network of authorized repair providers.

- Restricting access to telemetry data, such as logs generated during the normal operation of devices.

- Unlawfully asserting patent rights and enforcing trademarks.

- Discouraging the use of non-OEM parts and independent repair services.

- Using Digital Rights Management (DRM), technical protection mechanisms (TPM), and other forms of software restrictions.

Parts Pairing

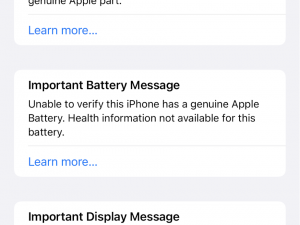

Parts pairing refers to software mechanisms used by electronic device manufacturers to ensure that their devices are only used with genuine manufacturer-supplied parts, and that repairs are only performed by authorized technicians with special software tools. A device that utilizes "parts pairing" may store its original parts' serial numbers (or other identifying information) and periodically check whether the serial numbers of installed components match the original ones. If any mismatch is detected, the device may present the user with warning messages and have reduced functionality[8]. Parts pairing are currently used by various manufacturers on many types of devices, including smartphones, TVs, game consoles, etc., and it hampers independent repair providers — who rarely have access to genuine replacement parts and the required software tools — from performing repairs successfully.

For example, if an independent repair technician were to replace the battery on an Apple iPhone, the user would lose access to battery health information and be faced with a warning message informing them that their phone has a non-genuine battery, even if the technician installed a genuine Apple battery harvested from another iPhone of the same model[9].

Apple is not the only company implementing parts pairing. On the OnePlus Pad tablet, released in February 2023, OnePlus employs a similar parts pairing scheme on the device's battery. The manufacturer warns consumers against any repair attempts, and stated that the tablet's battery "has been especially encrypted for safety purposes. Please go to an official OnePlus service center to repair your battery or get a genuine replacement battery." While it is currently unclear what they mean by "encrypting" batteries, Ron Amadeo – an editor at Ars Technics – speculates that "there is a serial number check in the firmware somewhere and that it will presumably refuse to work if you replace [the battery]." Unfortunately, Amadeo found that there is no "official OnePlus service center" in the U.S., which means U.S. consumers are limited to mail-in service only [10].

Benefits of Right to Repair

Ensure accessible and affordable repairs

Repairing electronic devices with minor failures and extending their lifespan is considerably more cost-effective than replacing them, according to an estimate performed by the U.S. Public Interest Research Group (US PIRG). Repair could reduce household spending on electronic devices and appliances by 22 percent, which would save an average American household approximately $330 per year. In other words, across 122 million American households, repair could save Americans $40 billion annually. With a robust repair ecosystem of both manufacturer-authorized and independent repair providers, and more people in local communities serving as independent repair technicians and performing repairs, the cost and speed of repair services are expected to decrease. However, if manufacturers restrict independent repair, repair turnaround and costs will remain high, and consumers would purchase replacement devices instead of replacing their existing ones[11].

Foster innovation

The Open Source Software and Maker Movements, both of which assert that consumers have the right to fix or modify any product they own, has seen tremendous success in the 21st century. The products of these movements, including the Anduino microcontrollers, Raspberry Pi computers, and the RepRap 3D printer project, are integral parts of many modern technological innovations that continue to generate economical value. By extension, ensuring that consumers have the right to repair electronics devices empowers them to repair and tinker with their own devices, learn about their designs and functions, and use them in novel and innovative ways. This is in contrast to the "no user serviceable components inside" business model, where electronics device manufacturers advise consumers against repairing their own devices, and repairs should only be performed by authorized providers[12].

Reduce electronic waste (e-waste)

It is believed that the widespread availability of economical repair options can help reduce electronic waste. Right-to-repair advocates, such as Nathan Proctor from the U.S. Public Interest Research Group, argue that reuse and repair of usable technology should be preferred over recycling, as reuse generates substantially less e-waste and reduces the carbon footprint associated with manufacturing, use, and recycling of devices[13]. Therefore, repair and reuse are considered to be more environmentally friendly.

Currently, many consumers may choose to dispose of devices with minor malfunctions and replace them over repairing failed devices, due to the lack of economically viable repair options. A web-based survey about how consumers understand repair conducted by Dr. Aaron Perzanowski — Professor of Law at the University of Michigan Law School — in 2020 found that 86% of respondents (N=838) had replaced, discarded, or recycled a smartphone or tablet due to common hardware failures. Amongst such failures, display damages and battery issues are the most prevalent, and both of these malfunctions are easily repairable[14].

Consumers' decision to replace instead of repair has considerable environmental consequences. Mining and refining raw materials, manufacturing parts, assembling, and shipping completed electronic devices consume substantial amounts of energy and create significant carbon footprint. All combined, nearly 70% of the carbon emission associated with an electronic device is generated during its production. Furthermore, e-waste is the fastest growing waste category on Earth, and its recycling is far from ideal. Only about 20% of e-waste is properly recycled[15]. The majority are often disposed of in landfills, where hazardous chemicals — including lithium, mercury, and lead — are released to the environment[16].

Opposition

Since its inception, the Right to Repair movement has faced opposition from electronic device manufacturers and lobbying groups representing them[17].

Patents and proprietary information

Electronics device manufacturers often argue that measures proposed by Right-to-Repair legislation may violate their rights to patents, trade secrets, and other types of proprietary information.

In late January 2019, 16 trade associations representing electronics manufacturers issued a joint statement in response to Hawaii's then-proposed Right to Repair legislation (SB 425). In the statement, they stated that given the scope of what must be provided under the legislation (including tools, parts, diagnostics utilities, and software updates), it's highly likely that some of such information is proprietary. As a result, making such information public without the contractual safeguards between manufacturers and authorized repair providers puts the manufacturers' intellectual property at risk[18].

Safety and security concerns

Anti Right-to-Repair lobbyists and electronics device manufacturers often argue that requiring manufacturers to sell repair parts and provide documentation may compromise the security of users and their data. In 2018, the Security Innovation Center, a now-defunct lobbying group, claimed that measures enforced by proposed Right-to-Repair legislation may expose consumers' sensitive data to threat actors, as modern electronic devices are capable of connecting to each other and the Internet. Specifically, Josh Zecher — Executive Director of The Security Innovation Center — stated during a phone interview that “if everyone is writing to the (operating system) and doing other patches, there’s the potential for embedding malware or additional code that’s not there from the manufacturer,” which could compromise devices and their users' security and privacy[19].

Manufacturers also claim that unauthorized repairs performed by consumers or independent technicians may lead to quality issues and safety hazards. For example, Apple highly encourages consumers to have their Apple devices repaired by Apple-certified technicians who have completed Apple repair training and use genuine Apple parts, since uncertified or untrained repair providers may not follow Apple's strict guidelines that ensures safe and high-quality repairs. Additionally, an improperly-performed repair may cause inadvertent damage to a device's lithium batteries, which could cause fires and injuries[20].

Circumvention of copy protection

Many modern electronic devices employ software and hardware mechanisms to safeguard digital content creators from copyright infringement and prevent illegal copying of copy-protected digital media, including movies, music, and video games. Such techniques, also known as Digital Rights Management (DRM) or Technological Protection Measures (TPM), require specialized software and devices free from tampering.

For example, publishing repair specifications for video game consoles could allow an unauthorized person to modify consoles and compromise copy protection (DRM) systems, which can present significant potential for piracy risks. Since game console manufacturers are responsible for protecting not only their devices, but also the games developed by various entities, the piracy risks could have detrimental impacts on the video game industry and undermine the entire console ecosystem[21].

Furthermore, a coalition of 16 trade associations representing electronics manufacturers expressed similar concerns in a statement to Hawaii state legislature:

Consumer electronics use on-board software (i.e., firmware) to help control the product. That firmware is subject to copyright under federal law, and Section 1201 of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, a related federal law, ensures that bad actors cannot tamper with the digital rights management that copyright owners use to protect this software. The problem is that making repairs to hardware components may necessitate modifying the firmware so that the product will work again.

Right to Repair in the United States

State legislation

As of January 2023, 27 U.S. states have introduced some form of Right to Repair legislation. These bills would mandate manufacturers of electronic equipment to respect the Right to Repair by providing access to replacement parts, service manuals, diagnostics and other special tools needed for device repairs. Although not all states' proposed Right to Repair bills apply to electronic devices, as some specifically target agricultural or medical equipment, bills proposed in the vast majority of the 27 states apply to a broad range of equipment, including electronics devices[22].

State-level legislative effort has not been very successful. Although over half of U.S. states have introduced Right to Repair bills, few has been passed and signed into law.

In June 2022, New York became the first state passing a Right to Repair bill. The Digital Fair Repair Act (New York Senate Bill S4104A) passed through both legislative chambers in New York nearly unanimously, and Governor Kathy Hochul signed an altered version of the Act into law on Dec 29, 2022[24]. The bill has been highly praised by the Federal Trade Commission, but it has faced pushbacks from device manufacturers. As a result, the signed version has been edited in several ways, and it is considered to be weaker than the original version passed by New York legislatures. The amended version only applies to devices first sold after June 1, 2023, and allows device manufacturers to provide assemblies of parts rather than individual components[25]. Nonetheless, the bill has received acclaim from right-to-repair advocates, as the access to repair parts and tools (which is now required in New York) cannot be easily contained to one state[26].

Federal Trade Commission (FTC)

The FTC's 2019 report Nixing the Fix details the hardships repair restrictions create for consumers and businesses, and the Commission is concerned that such burden is borne heavily by low-income families and small businesses. As a result, the FTC is in favor of competition in repair services and supporting independent repair. Providing more choices in repair can enable timely and economic repairs, reduce e-waste, and provide opportunities for entrepreneurs and local businesses[27].

In absence of legislation, FTC rules can offer consumers and independent repair technicians some amount of Right to Repair. For example, the FTC could implement a "fair repair" rule that requires electronics device manufacturers to and sell replacement parts and provide diagnostics software to the public[28].

On July 21st, 2021, the FTC voted 5-0 and unanimously approved a policy statement aimed at restoring the Right to Repair for all. The Commission plans to strengthen law enforcement against repair restrictions that prevent individuals from fixing their own devices [29].

FTC Chair Lina M. Khan stated this during an open Commission meeting:

These types of restrictions can significantly raise costs for consumers, stifle innovation, close off business opportunity for independent repair shops, create unnecessary electronic waste, delay timely repairs, and undermine resiliency. The FTC has a range of tools it can use to root out unlawful repair restrictions, and today’s policy statement would commit us to move forward on this issue with new vigor.

President Biden

On July 9th, 2021, U.S. President Biden signed Executive Order 14036, Promoting Competition in the American Economy[30]. The Order, mainly aimed to improve competition in the American economy, condemns manufacturers' anticompetitive behaviors that restrict self-repair or independent repair services[31]. Specifically, the Order encourages the Chair of the FTC to exercise the FTC's authority in areas such as the "unfair anticompetitive restrictions on third-party repair or self-repair of items"[32].

See also

References

- ↑ Purdy, K. (2020, March 13). How to get involved with right to repair. iFixit. Retrieved February 7, 2023, from https://www.ifixit.com/News/35268/how-to-get-involved-with-right-to-repair

- ↑ Purdy, K. (2019, October 29). Here are the secret repair tools apple won't let you have. iFixit. Retrieved January 21, 2023, from https://www.ifixit.com/News/33593/heres-the-secret-repair-tool-apple-wont-let-you-have

- ↑ Proctor, N. (2023, January 4). Right to repair in 2022: What happened in New York, and our top accomplishments. PIRG. Retrieved January 26, 2023, from https://pirg.org/articles/right-to-repair-in-2022-what-happened-in-new-york-and-our-top-accomplishments/

- ↑ Reinauer, A. (2022, April 7). "Right to Repair" Bill is a move in the wrong direction. Competitive Enterprise Institute. Retrieved January 24, 2023, from https://cei.org/blog/right-to-repair-bill-is-a-move-in-the-wrong-direction/

- ↑ The Repair Association. Learn about the right to repair. The Repair Association. Retrieved January 21, 2023, from https://www.repair.org/stand-up

- ↑ Policy Statement of the Federal Trade Commission on Repair Restrictions Imposed by Manufacturers and Sellers. Federal Trade Commission. Retrieved January 22, 2023, from https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/public_statements/1592330/p194400repairrestrictionspolicystatement.pdf

- ↑ Greenlee, L. (2023, January 17). How parts pairing kills Independent Repair. iFixit. Retrieved February 7, 2023, from https://www.ifixit.com/News/69320/how-parts-pairing-kills-independent-repair

- ↑ Greenlee, L. (2023, January 17). How parts pairing kills Independent Repair. iFixit. Retrieved February 7, 2023, from https://www.ifixit.com/News/69320/how-parts-pairing-kills-independent-repair

- ↑ Greenlee, L. (2023, January 17). How parts pairing kills Independent Repair. iFixit. Retrieved February 7, 2023, from https://www.ifixit.com/News/69320/how-parts-pairing-kills-independent-repair

- ↑ Amadeo, R. (2023, February 7). OnePlus takes on the iPad with the OnePlus Pad. Ars Technica. Retrieved February 10, 2023, from https://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2023/02/oneplus-takes-on-the-ipad-with-the-oneplus-pad/

- ↑ Repair Saves Families Big. U.S. PIRG. (2021, January). Retrieved January 22, 2023, from https://pirg.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Repair-Saves-Families-Big_USP_Jan2021_FINAL1a.pdf

- ↑ Goldberg, L. (2018, February 1). Protecting the right to Tinker. Design World. Retrieved February 8, 2023, from https://www.designworldonline.com/protecting-the-right-to-tinker/

- ↑ Proctor, N. (2023, January 4). Right to repair in 2022: What happened in New York, and our top accomplishments. PIRG. Retrieved January 26, 2023, from https://pirg.org/articles/right-to-repair-in-2022-what-happened-in-new-york-and-our-top-accomplishments/

- ↑ Perzanowski, Aaron (2021) "Consumer Perceptions of the Right to Repair," Indiana Law Journal: Vol. 96: Iss. 2, Article 1. https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj/vol96/iss2/1

- ↑ Stone, M. (2021, November 11). Could letting consumers fix their iPhones help save the planet? Grist. Retrieved January 24, 2023, from https://grist.org/article/could-letting-consumers-fix-their-own-iphones-help-save-the-planet/

- ↑ Wisniewska, A. (2020, January 10). What happens to your old laptop? the growing problem of e-waste. Financial Times. Retrieved January 24, 2023, from https://www.ft.com/content/26e1aa74-2261-11ea-92da-f0c92e957a96

- ↑ Povich, E. S. (2019, October 16). Tech Giants fight digital right-to-repair bills. The Pew Charitable Trusts. Retrieved January 26, 2023, from https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2019/10/16/tech-giants-fight-digital-right-to-repair-bills

- ↑ Electronics Manufacturers Opposition to SB 425 (Electronic Equipment Repair). Hawaii State Legislature. (2019, January 30). Retrieved February 7, 2023, from https://www.capitol.hawaii.gov/sessions/Session2019/Testimony/SB425_TESTIMONY_TEC_01-31-19_.PDF

- ↑ Roberts, P. (2018, February 24). Updated: A new lobbying group is fighting right to repair laws. The Security Ledger. Retrieved February 6, 2023, from https://securityledger.com/2018/02/new-lobbying-group-fights-right-repair-laws/

- ↑ Questions for Mr. Kyle Andeer, Vice President, Corporate Law, Apple, Inc. U.S. House of Representatives. (n.d.). Retrieved February 6, 2023, from https://docs.house.gov/meetings/JU/JU05/20190716/109793/HHRG-116-JU05-20190716-SD036.pdf

- ↑ Right to Repair. The Entertainment Software Association. (n.d.). Retrieved February 9, 2023, from https://www.theesa.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/ESA-PolicyPapers_RTR_final.pdf

- ↑ Proctor, N. (2021, March 10). Half of U.S. states looking to give Americans the right to repair. PIRG. Retrieved January 21, 2023, from https://pirg.org/articles/half-of-u-s-states-looking-to-give-americans-the-right-to-repair/

- ↑ Proctor, N. (2021, March 10). Half of U.S. states looking to give Americans the right to repair. PIRG. Retrieved January 21, 2023, from https://pirg.org/articles/half-of-u-s-states-looking-to-give-americans-the-right-to-repair/

- ↑ Waddell, K. (2022, October 3). A New State Law Could Make It Easier to Fix Your Electronics — But It’s in Limbo. Consumer Reports. Retrieved January 22, 2023, from https://www.consumerreports.org/right-to-repair/new-state-law-could-make-it-easier-to-fix-your-electronics-a1914917475/

- ↑ Clukey, K. (2022, December 29). NY becomes first state with electronics right to repair law. Bloomberg Law. Retrieved January 22, 2023, from https://news.bloomberglaw.com/environment-and-energy/ny-becomes-first-state-to-pass-electronics-right-to-repair-law

- ↑ Waddell, K. (2022, October 3). A New State Law Could Make It Easier to Fix Your Electronics — But It’s in Limbo. Consumer Reports. Retrieved January 22, 2023, from https://www.consumerreports.org/right-to-repair/new-state-law-could-make-it-easier-to-fix-your-electronics-a1914917475/

- ↑ Policy Statement of the Federal Trade Commission on Repair Restrictions Imposed by Manufacturers and Sellers. Federal Trade Commission. Retrieved January 22, 2023, from https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/public_statements/1592330/p194400repairrestrictionspolicystatement.pdf

- ↑ Wiens, K. (2021, July 13). The Biden administration thinks you should be allowed to fix the things you buy. The Washington Post. Retrieved January 21, 2023, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2021/07/13/biden-ftc-right-to-repair/

- ↑ FTC to ramp up law enforcement against illegal repair restrictions. Federal Trade Commission. (2021, July 21). Retrieved January 21, 2023, from https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2021/07/ftc-ramp-law-enforcement-against-illegal-repair-restrictions

- ↑ Promoting Competition in the American Economy. Federal Register. (2021, July 9). Retrieved January 21, 2023, from https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2021/07/14/2021-15069/promoting-competition-in-the-american-economy

- ↑ Wiens, K. (2021, July 13). The Biden administration thinks you should be allowed to fix the things you buy. The Washington Post. Retrieved January 21, 2023, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2021/07/13/biden-ftc-right-to-repair/

- ↑ Promoting Competition in the American Economy. Federal Register. (2021, July 9). Retrieved January 21, 2023, from https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2021/07/14/2021-15069/promoting-competition-in-the-american-economy