COVID-19 Data Privacy

COVID-19 data privacy concerns refer to the balance between health and privacy during the pandemic, and the concerns that citizens have over their personal information. As COVID-19 caused a global emergency in March of 2020, several restrictions were implemented by governments and institutions in order to save lives. Mounting evidence demonstrates that the collection, use, sharing, and further processing of data can help limit the spread of the virus and aid in accelerating the recovery, especially through digital contact tracing[1]. Data collection could include vast amounts of personally and/or non-personally sensitive data. There have been several concerns from the public that certain measures put in place during the COVID-19 pandemic have led to the infringement of fundamental human rights and freedoms.

Contents

Concerns by Country

China

China, known as "Country-0" for the global pandemic[3], used artificial intelligence, cloud computing, big data, blockchain and 5G to control the spread of COVID-19[4]. Baidu Research, a leader in AI research and development, open-sourced its linear-time AI algorithm called LinearFold to epidemic prevention centers, gene testing institutions, and global scientific research institutions[4]. This algorithm reduced the time taken to predict and study coronavirus’s RNA secondary structure from 55 minutes to just 27 seconds, ultimately improving speed 120 times[4]. Furthermore, artificial intelligence was developed for the Beijing subway police to identify commuters who were not wearing masks, and new temperature measurements were created to quickly take commuters' temperatures. All of these measures were implemented without the consent of passengers[4]. Baidu also has an online consultation service, which has handled over 15 million inquiries[5].

Chinese legislation doesn’t limit Baidu in what they can do with health information from its users, giving power to a company whose intentions may be unclear[5]. Furthermore, Qihoo 360, a Chinese internet company who has a history of inappropriate data collection and usage[6], posted a Big Data Migration Map, which allowed citizens to view the trends and hotspots of COVID-19[4]. Another company, Alibaba, known as the world’s largest e-commerce firm, launched a drug delivery service to treat people with chronic illnesses. The service entered health information from patients into an extensive database, which also tracked their online purchases[5]. Alongside these resources, an app was launched by China Mobile, China Telecom, China Unicom, and China Academy of Information and Communications Technology (CAICT), called Telecommunication Data Based Travel Itinerary Card[7]. With the consent from the user, this app tracks travel history and reports a color card to prove if the user is or is not safe. The app disclaims the collection national ID numbers, home addresses, or other data, however, privacy concerns have surfaced[8]. In August of 2019, Comparitech ranked the world’s top ten most surveilled cities with Chinese cities receiving eight of the ten spots[9], and 95% of respondents to a survey from a Chinese newspaper stated their personal data had been stolen, making it unsurprising that the country has enough data on their citizens to control the pandemic [8].

South Korea

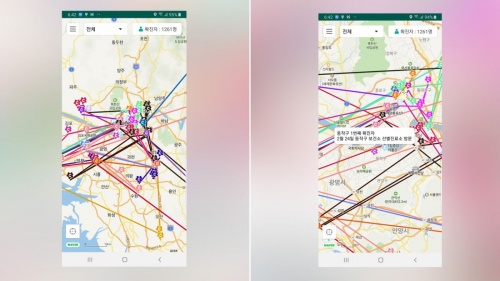

In South Korea, the government has taken actions to combat the virus by tracking the movements of its citizens who have tested positive for COVID-19. These different tracking measures include credit/debit card transactions, phone GPS, and South Korea’s own surveillance cameras.[10] The country argues these methods help them trace the whereabouts of infected persons before they were notified and inform people who may have been in contact with them. The system also publicly shares patient info, and regularly scrutinizes to impede individuals’ privacy.

South Korea is often praised for their ability to stop COVID-19 from spreading early on in the pandemic. This success may be attributed to having to handle a previous viral outbreak in 2015, known as the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) outbreak. Learning from this experience, South Korea implemented a Reform of the National Infectious Disease Response System[11] outlining how they will address future viruses. The results of these guidelines increased public surveillance and public health tracking tools. In the wake of COVID-19, they launched an app, Self Quarantine Safety Protection App, for users to report symptoms and monitor individuals in quarantine to ensure they do not leave their respective homes.[12]

Israel

When Israel ordered citizens to stay at home, they used a cell phone tracking tool, which was previously designed to track terrorists, so that the government could identify if citizens were breaking protocols. Some politicians in Israel referred to the mobile phone tracking system as an assault on the privacy of Israelis. Supercom, a biometric company headquartered in Israel, introduced an electronic monitoring and tracking platform for the population.[14]

United States

In the US, the government partnered with the data-mining company, Palantir, to model the virus outbreak. The government also worked with various companies to scrape public social media data to monitor public discussion of symptoms. Furthermore, they had active talks with Facebook and Google (among others) about using location data from Americans’ phones to map the spread of the infection.[15]

United Kingdom

Public Health England (PHE) is an executive agency of the government that makes an effort to maintain transparency while the COVID-19 pandemic continues to spread. Their current goal is to protect and improve the nation’s health and wellbeing while attempting to control the spread of COVID-19. They claim to only collect demographic, health, and treatment information when absolutely necessary. This information can come from the individual directly, their healthcare providers, or from a variety of organizations (NHS Digital, National Pathology Exchange, etc.) that are approved for collecting sensitive information in the interest of public health. The legal basis that allows this collection and handling of personal health information includes the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the Data Protection Act of 2018 [16].

In July of 2020, the UK government broke their own privacy laws to implement a new test-and trace-system. Although the National Health Service (NHS) application is completely voluntary, a full assessment of the privacy implications was not completed before its implementation [17]. This led to a minimum of three different data breaches across the country. The data protection implement assessment (DPIA) is a safety step required by law before processing any “high risk” personal data. The government claimed it was not “high risk” data, but then openly admitted to their mistake after the Open Rights Group (ORG) threatened to take them to court [18].

More recently, a new technology has been developed by UK-based company, Anglo American. Its intentional use is to limit the spread of communicable diseases in the work place for not only COVID-19, but future viruses. This product is still in the testing phase, but has already partnered with the popular South Korean company, Samsung, to make and distribute them eventually. It is essentially a fitness watch that works as a test-and-trace tool. It can log up to 8,000 contact events a day and can even set off an alarm sound when social distancing rules are being breached. This product has the potential to slow the spread of COVID-19, but the threats to privacy it may pose are something yet to be considered [19].

Concerns by Practice

Contact Tracing

Contact tracing is the process of identifying individuals who may have come into contact with an infected person and subsequent collection of further information about these contacts. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), data protection and privacy laws need to be in place to provide a legal basis for data processing, restrictions on data use, measures to establish oversight, and sunset clauses to dismantle certain technologies. The WHO also outlined several principles for the appropriate use of tracking technologies, which include time limitation, data minimization, and transparency.[20]

Testing

COVID-19 testing has led to increased data collection from citizens. Personal data and test results are sometimes shared freely between health care providers and public health officials. In some cases, first responders have been given the addresses of people who have tested positive for COVID-19. Several countries, including the UK, US, and Germany, have considered using antibody test information as “immunity certificates”.[21] There have been concerns that employers testing their workers for COVID-19 could inadvertently collect biometric information in violation of state privacy laws.[22]

Vaccines

Vaccinations for COVID-19 require data collection from the general public. In an effort to vaccinate the population quickly, Philadelphia partnered with a nonprofit, Philly Fighting COVID. It was eventually discovered that the nonprofit changed its status to ‘for profit’ and its privacy policy claimed that it could sell preregistration data it collected. The data it collected included name, birthday, address, and occupation.[23] There have also been concerns that collecting personal data could dissuade undocumented people from getting vaccinated.[24]

Health Code

Health Code was launched by the Chinese government during the COVID-19 pandemic to serve as a digital passport when traveling and entering public areas. It is now widely used in mainland China area and was now introduced to Hong Kong S.A.R. There are three health levels, representing the risk of a person infected by COVID-19, with green representing normal people while red representing the highest risk level. Chinese official media Xinhua claimed that this helps to promote work and production resumption. [25] However, this also raised several ethical issues. The health code records one's ID number, body temperature, and recent travel history. Telecom operators track people’s movements while social media platforms like WeChat and Weibo have hotlines for people to report others who may be sick. However, these data are entered by users but whether the health code collects more data and how the code works remain unknown. There have been complaints by Chinese social media users about a lack of transparency over how the app works and what data it is storing. Some reported being unable to change erroneous “red” designations. One resident complained on Weibo that he had driven through Hubei without stopping but his colour code changed to yellow from green, indicating he would need to be quarantined. Cite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag In Hangzhou, the authority published gradient colored health code, ranking based on how much they exercised, their eating and drinking habits, whether they smoked and even how much they slept the night before. This policy was seen as being too invasive and raised a storm of criticism in Weibo, an social media platform similar to Twitter. [26]

Future Concerns

Various factors surrounding COVID-19 data can potentially impact individuals in the future. If data is breached by cybercriminals through databases or apps, this could create an opportunity for identity theft. Although unknown who it would target, this could negatively impact many lives where their data and information is misused.[28] Criminals can also steal an individual’s identity by posting their paper vaccination card on social media. When they have access to your date of birth, it’s easier for them to piece together your social security number, giving them access to all of your personal information which can then be sold on platforms like the black market.[29]

Some countries, such as Isreal, have implemented a COVID-19 “vaccination passport” app created by companies like IBM[30] and The World Economic Forum.[31] These apps are designed to store vaccine and health data for individuals who have been fully vaccinated. Vaccine passes can be utilized to scan and get access to hotels, restaurants, gyms, and other open spaces. Although this would bring back some normalcy to our everyday lives, it could also be used to track individuals’ movements without their knowledge or consent.[32] Access to this proprietary information by owners of this data could reveal more than people anticipate. It can disclose habits, sexual preferences, religion, political affiliations, and different search results[33] people don’t know these applications have access to.

“Vaccine passport” apps could create a larger divide between those who have access to the vaccine and those who do not or do not plan on getting it themselves, portraying a skewed and unrealistic representation of data.

Legislation

Consumer Data Protection Act

Introduced in April 2020, the COVID-19 Consumer Data Protection Act,[34] would make it unlawful for a covered entity to “collect, process, or transfer the covered data of an individual” without prior notice and express consent unless necessary to comply with a legal obligation. Covered in the bill, entities would need to provide individuals with the right to opt-out from having data collected. Entities would also be required to delete information when it is no longer useful and minimize their collection of data.[35]

Public Health Emergency Privacy Act

Senators are trying to pass better privacy health laws in order reassure the public that their health information stays private. The Public Health Emergency Privacy Act[36] is one piece of legislation that would provide some legal safeguards. The act, introduced in May 2020, would do the following:

- Ensure that data collected for public health is strictly limited for use in public health;

- Explicitly prohibit the use of health data for discriminatory, unrelated, or intrusive purposes, including commercial advertising, e-commerce, or efforts to gate access to employment, finance, insurance, housing, or education opportunities;

- Prevent the potential misuse of health data by government agencies with no role in public health;

- Require meaningful data security and data integrity protections – including data minimization and accuracy – and mandate deletion by tech firms after the public health emergency;

- Protect voting rights by prohibiting conditioning the right to vote based on a medical condition or use of contact tracing apps;

- Require regular reports on the impact of digital collection tools on civil rights;

- Give the public control over their participation in these efforts by mandating meaningful transparency and requiring opt-in consent;

- Provide for robust private and public enforcement, with rulemaking from an expert agency while recognizing the continuing role of states in legislation and enforcement.

Notes

- ↑ World Health Organization. "Joint Statement on Data Protection and Privacy in the COVID-19 Response" 19, Nov. 2020

- ↑ https://www.coe.int/en/web/human-rights-rule-of-law/-/corona-apps-chair-of-the-committee-of-convention-108-and-data-protection-commissioner-on-the-need-to-avoid-unwanted-effects

- ↑ Duarte, F. (2020, February 23). Who is 'Patient Zero' in the Coronavirus Outbreak? Retrieved April 06, 2021, from https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20200221-coronavirus-the-harmful-hunt-for-covid-19s-patient-zero

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Xiaxoxia, Q. (2020, April 08). How Emerging Technologies Helped Tackle COVID-19 in China: World Economic Forum. Retrieved April 06, 2021, from https://perma.cc/TU48-DG2K

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Claypoole, Theodore. "COVID-19 and Data Privacy: Health vs. Privacy" 26, March 2020

- ↑ Obel, M. (2015, December 06). Privacy Issues With China's Qihoo 360 technology, Which Provides Free Antivirus Software, Are Becoming More Public; But Qihoo Strongly Rebuts Accusations. Retrieved April 06, 2021, from https://www.ibtimes.com/privacy-issues-chinas-qihoo-360-technology-which-provides-free-antivirus-software-are-1181437

- ↑ Fighting COVID-19. (n.d.). Retrieved April 06, 2021, from http://www.caict.ac.cn/english/research/covid19/202004/t20200426_280273.html

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Zhang, L. (2020, June 01). Regulating Electronic Means to Fight the Spread of COVID-19. Retrieved April 06, 2021, from https://www.loc.gov/law/help/coronavirus-apps/china.php#_ftn4

- ↑ Chen, L. (2020, January 27). China Wakes Up to Wide Web of Online Data Leaks And Privacy Concerns. Retrieved April 06, 2021, from https://perma.cc/S2N7-PCPS

- ↑ Cellan-Jones, Rory. "Tech Tent: Can we learn about coronavirus-tracing from South Korea?" 15, May 2020

- ↑ Jeong Jin-yeop. "Confirmation and announcement of plans to reform the national defense system"

- ↑ Kim, Max. "South Korea is watching quarantined citizens with a smartphone app" 6, March 2020

- ↑ Watson, Ivan. "Coronavirus mobile apps are surging in popularity in South Korea" 28, Feb. 2020

- ↑ Claypoole, Theodore. "COVID-19 and Data Privacy: Health vs. Privacy" 26, March 2020

- ↑ Grind, K., McMillan, R., and Wilde, A. "To Track Virus, Governments Weigh Surveillance Tools That Push Privacy Limits" 17, March 2020

- ↑ “COVID-19 Privacy Information.” GOV.UK, 1 Mar. 2021, www.gov.uk/government/publications/phe-privacy-information/covid-19-privacy-information.

- ↑ “Privacy in a Pandemic: A Comparison between the Contact Tracing Applications of India and the United Kingdom.” LSE Human Rights, 13 July 2020, blogs.lse.ac.uk/humanrights/2020/06/12/privacy-in-a-pandemic-a-comparison-between-the-contact-tracing-applications-of-india-and-the-united-kingdom.

- ↑ Marsh, Sarah, and Alex Hern. “Government Admits Breaking Privacy Law with NHS Test and Trace.” The Guardian, 20 July 2020, www.theguardian.com/technology/2020/jul/20/uk-government-admits-breaking-privacy-law-with-test-and-trace-contact-tracing-data-breaches-coronavirus.

- ↑ McKay, David. “Anglo Is Watching You ... How the UK Group Is Hoping to Contain Covid-19 at Work.” Miningmx, 9 Apr. 2021, www.miningmx.com/uncategorized/45662-anglo-is-watching-you-how-the-uk-group-is-hoping-to-contain-covid-19-at-work.

- ↑ World Health Organization. "Ethical considerations to guide the use of digital proximity tracking technologies for COVID-19 contact tracing" 28, May 2020

- ↑ Bracy, Jedidiah. "Should first responders know the addresses of those with COVID-19?" 10, April 2020

- ↑ https://www.businessinsurance.com/article/20201110/NEWS06/912337665/Workplace-COVID-19-testing-raises-biometric-privacy-concerns-Michael-Jerinic-v-

- ↑ Morrison, Sara. "Are vaccine providers selling your health data? There’s not much stopping them." 28, Jan. 2021

- ↑ Drees, Jackie. "State officials express privacy concerns over CDC's call for COVID-19 vaccine data registry" 8, Dec. 2020

- ↑ Xinrong He, Jiefei Hu "Helps promote public health, instead of blocking anti-pandemic" Xinhua She

- ↑ Josh Horwitz, Brenda Goh "As Chinese authorities expand use of health tracking apps, privacy concerns grow" The Reuters

- ↑ IBM.“IBM Digital Health Pass”

- ↑ Altuglu, V., Salgado, M., Celmanbet, O., Haque, R., Yanguas, L. “Assessing Damages in Data Privacy and Data Breach Class Actions Involving Health Data in the Wake of COVID-19” 15, March 2021

- ↑ Irick, Whitney.“Here's Why You Shouldn't Post Your COVID-19 Vaccine Card on Social Media” 17, March 2021

- ↑ IBM.“IBM Digital Health Pass”

- ↑ World Economic Forum.“Common Trust Network”

- ↑ WKRC.“Why COVID-19 "vaccine passports" could be "Pandora's box" for data privacy, ethical issues” 15, March 2021

- ↑ Bernal, Paul.“Data gathering, surveillance and human rights: recasting the debate” 2016

- ↑ Fazlioglu, Muge.“Republican senators to introduce the COVID-19 Consumer Data Protection Act” 1, May 2021

- ↑ U.S. Senate.“S.3663 - COVID-19 Consumer Data Protection Act of 2020” 7, May 2021

- ↑ U.S. Senate.“S.3749 - Public Health Emergency Privacy Act” 14, May 2021