Apple's App Tracking Transparency

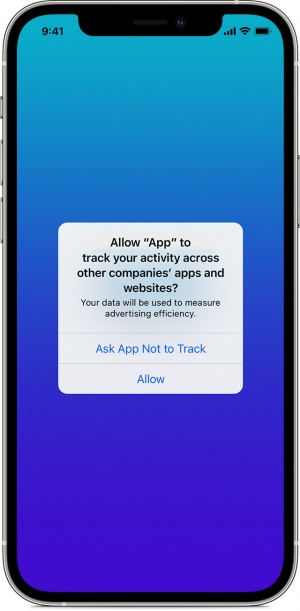

Apple’s App Tracking Transparency is a privacy feature released in iOS 14 requiring apps to obtain permission from a user before collecting information from their activity across other apps. This feature changes user data collection from being automatically opted-in to being automatically opted-out. Users also have the option to disable apps from asking if they are able to track, automatically opting out users from tracking instead. [2] This new feature is one of many steps Apple has taken to increase user privacy and trust across their devices. Other measures include social widget tracking prevention, privacy reports, intelligent tracking prevention, and fingerprinting defense.[3] Many believe that this step has been a good step in reducing classification and increasing privacy. Others, however, argue that targeting and classification will still occur, just without tracking of specific user data. [4]

Contents

Activating and Deactivating Tracking

Apple’s App Tracking Transparency is automatically turned on when first updating a device to iOS 14 or higher. To turn off the pop-ups, Apple users can turn off ATT by going to Settings, then Privacy & Security, then Tracking, and turning off the option Allow Apps to Request to Track. By disabling this feature, ATT automatically opts users out of tracking without sending a pop-up notification on future apps.

If a user chooses to allow an app to track their data but later decides they wish to opt out of sharing, they can navigate to the specific app within the Tracking portion of settings and turn the slider to the off position.

Identifier For Advertisers (IDFA)

Every Apple device contains a unique identifier called an Identifier for Advertisers (IDFA) that collects information from its given user without disclosing personal identification information about the user themself. [5] By tracking information about the actions and behaviors of the user across the device rather than the personal information provided by the user, Apple is able to uphold a level of anonymity about the specific identity of the user of each device.

Even with the identity of the user anonymized, advertisers are still able to gain mass amounts of information through the IDFA to produce customized advertising to the user. Companies are not able to learn specific information regarding the user, but they are able to aggregate the data to still directly market towards each user. This practice protects an individual’s privacy by reinforcing anonymous categorization.

When the IDFA was originally created, Apple automatically opted users into sharing their collected app data with the IDFA. Users could choose to opt out of sharing their information by going into settings and turning off this sharing option. With the new iOS 14 update, App Tracking Transparency automatically opts users out of sharing this information rather than automatically opting them into the IDFA. This feature was always technically optional, but the new release requires users to choose to share their data, rather than requiring users to choose not to share their data. [6]

Company Responses to ATT

Facebook has been largely outspoken against the development of App Tracking Transparency since Apple first released information regarding the new project. One of Meta’s main concerns that representatives have publicly voiced regarding the development of ATT is that implementing such a feature will negatively impact smaller businesses looking to create free applications for the public. [7] Free applications typically function through the use of advertisements where advertisers will pay companies to advertise on their app, thus allowing the companies to profit while keeping the app free to users. Limiting the user data shared to an application will decrease the amount of data the company can offer to advertisers, thus making the advertising experience less personalized, and less desirable to both users and advertisers. Facebook also argues that the prompt displayed by Apple discourages users from sharing data, rather than offering an unbiased option to choose whether or not to allow an app to track their data. [8] This dissuasion away from sharing data, Facebook officials argue, is not a form of Apple actually trying to increase privacy for users, but rather a method in which Apple can appear to care about user’s privacy in an effort to create more revenue for the company. [9]

Facebook itself is a free app that relies heavily on advertisements and the sharing of user data in order to gain revenue from users. With the release of App Tracking Transparency on Apple products, Facebook was estimated to lose around $12 billion due to the reliance of the company on their agreements with advertisers. [10] Additionally, the announcement of this new feature caused both a decrease in the number of Facebook users as well as a significant drop in the stock value of Meta. [11] Facebook took a heavy hit not only from the release of iOS 14 and ATT, but also from the announcement of the feature itself. Facebook has faced many criticisms in the past against its storage, use, and selling of user data across the platform. In 2018, Facebook faced a class-action lawsuit claiming that the platform sold user data without the consent of users which was then used for political benefits. This lawsuit was settled in 2022 with Facebook agreeing to pay a $725 million settlement. [12] Facebook also has faced another lawsuit following the release of the App Tracking Transparency feature, in which researchers have claimed that Facebook is undermining and disregarding the ATT feature, against the policies of Apple through the use of third-party tracking across websites visited by users. [13] Facebook and Meta representatives currently deny this claim as the case is in review.

About a year after the release of Apple’s App Tracking Transparency, Google announced their work on a similar project aimed at protecting the privacy of its users both across the web and across android devices. This new feature is currently called The Privacy Sandbox. The Privacy Sandbox is yet to be released to the public, and there is currently little data from Google regarding what strategies they wish to utilize to implement this feature. According to the information currently released by Google, this feature is meant to protect user data while still maintaining an environment where applications and websites can remain free to users while still churning a profit for companies. [14] Google has been negatively outspoken about other forms of privacy protection since the release of Apple’s App Tracking transparency claiming that these other forms are ineffective means to protect user data, and not considerate of the need to maintain a generally free online world. [15] Google aims to publicly release The Privacy Sandbox in 2024 or later.

Twitter has provided multiple resources to their users to further disclose their relationship with the new App Tracking Transparency framework. Within the Twitter Help Center, users can find an explanation of the new pop-up produced by Apple devices and how users can activate and deactivate tracking. [16] Twitter also discloses the use of tracking to its users through its privacy policy. When users opt in to share their data, Twitter states that they use that data to provide a personal experience to the users, and further improve the site as a whole. [17]

Twitter has faced most impacts of the App Tracking Transparency from the advertising side of Twitter, as they can no longer identify users as easily, which decreases Twitter’s ability to track the success of advertising campaigns, as well as other factors measured by individual users. [18] Developers have been careful to inform users of the importance of opting in to tracking through both the provided-pop, and the Twitter Help Center in order to help maintain user data tracking through App Tracking Transparency framework.

History of Apple Privacy

On April 29, 2005, Apple released Safari 2.0, which included the world’s first private browsing mode. Soon after, Google Chrome, Internet Explorer, and Mozilla Firefox all followed suit to release their own version of private browsing. Private browsing differs from typical web browsing, as it does not store browsing history and user data, whereas in a non-private browser, data is stored to help complete web searches and more accurately identify useful websites for users. [19] This feature protects local browser cookies, but does not aim to protect other forms of tracking such as third-party data and advertising. The term ‘private browsing’ has been misinterpreted by some users as meaning full privacy protection, whereas the feature only truly protects local browsing privacy. [20]

On June 29, 2007, the very first iPhone was released. All iPhone from the very first iPhone and on are associated with a Unique Device Identifier (UDID) that gives developers and advertisers a way to differentiate between iPhone users. At the time of its initial release, Apple had no features to erase cookies or block unwanted sources from viewing the UDID. It was therefore possible for data regarding specific personal information about users to be gathered, shared, and sold across a large window of potential buyers. [21] Users themselves were not identified, but each user operating on an individual device could have their data unknowingly shared across a vast array of interested parties.

On September 19, 2012, Apple released the IDFA with iOS 6, replacing the use of the UDID for advertisers. Additionally, Apple has taken steps to prevent advertisers from accessing the UDID altogether, instead requiring them to use the IDFA of a device instead. [22] The main difference between the IDFA and the UDID is that the IDFA grants users the ability to choose whether or not certain applications can obtain their data, whereas the UDID was open for anyone to be able to access.

On September 15, 2015, Apple released iOS 9 which included the ability to introduce Content Blockers on Safari. Users are now able to block advertisements appearing within Safari, allowing for a more streamlined and less distracted browsing experience. [23] Content Blockers do not affect what data is being collected from users, but it does give users control over the advertisements they see, which are often displayed uniquely according to each user’s collected data.

On June 5, 2017, Apple introduced Intelligent Tracking Prevention (ITP) on iOS 11, which disabled the use of third-party cookies, helping to prevent tracking of users across the web. [24] ITP received many updates, including releases of ITP 1.1, 2.0, 2.1, 2.2, and 2.3 from 2017 to 2019. The ITP helps prevent social widget tracking by automatically opting the user out of these third party cookies, producing a pop-up to ask the user if they wish to allow the site to track their cookies instead. Intelligent Tracking Prevention also includes social widget tracking prevention. Social widgets such as “like” buttons or comment sections are personalized to each logged-in user, which allows websites to gather information from the user without the need for the user to interact with these widgets. Since the release of ITP, Safari has integrated this social widget tracking prevention to block websites with social widgets such as “like” buttons or comment sections from gathering user data without the knowledge of the users. [25]

On September 16, 2020, iOS 14 brought App Tracking Transparency to Apple devices. The release of ATT has led to a disintegration of the IDFA by bringing data tracking to light for Apple users. [26] Currently, with only a small percentage of users opting in to submit data to the IDFA, the database is being filled with empty data, rather than useful figures for advertisers. Without data, the IDFA is not useful for advertisers, requiring them to find other sources for their data needs.

On September 20, 2021, iOS 15 was released by Apple, which included the addition of the Privacy Report feature. This feature offers users the ability to view just how often applications are accessing the permissions granted by users to gather data outside of the IDFA. [27] This report includes the use of various iPhone features such as the microphone, camera, and the user’s location. The Privacy Report can be found within the Settings section of an Apple device.

The Future of Apple's User Data Tracking

Along with the release of ATT, Apple also released a feature called Privacy Nutrition Labels. These labels inform users of the types of data that specific apps are collecting, in order for more full disclosure of user tracking. However, some of the Privacy Nutrition Labels released by applications are false or misleading, negating their usefulness in providing more information to users. [28] Most often, these misleading labels are produced by applications created by smaller companies. These smaller companies are strongly affected by the introduction of ATT, as these companies do not have access to the vast amounts of user data that companies such as Facebook and Google still maintain outside of the IDFA. [29] Many of these larger corporations have taken a hit in revenue from failure to retrieve useful information from the IDFA, but the large teams of developers and researchers employed by these companies have found ways to gather user data outside of this individual source. Smaller businesses do not have access to such resources, both in terms of employment size and in terms of the size of information already accessed and stored.

After the introduction of ATT, only about 20% of users have opted in to share their data to the IDFA. [30] The amount of information collected and stored within the IDFA has dramatically decreased since iOS 14. Although the introduction of this feature is meant to aid in reducing privacy concerns for users, there are still some ways in which Apple collects user data. Apple discloses a few ways in which user data is transported or sent to other sources without requiring permissions through App Tracking Transparency. These situations include, transferring data locally, passing along information relevant to fraud and security purposes, and through sharing data regarding creditworthiness. [31] Additionally, users that opt out of the IDFA are still submitting data to Apple’s SKAdNetwork. SKAdNetwork is a collection of data surrounding ads presented on Apple products. This data is not specific per user, but is rather aggregated to ensure group anonymity. Advertisers then receive this grouped feedback, allowing them to measure the success of their ads in a way that more strictly conceals the identities of users. [32]

Another strategy Apple has implemented in an effort to prevent non-consensual user data tracking is fingerprinting defense. Fingerprinting is the generation of an online persona of a user, created by companies through gathering data about a user. This gathered data can include aspects about a user’s computer, browsing habits, location, preferences, and more. [33] Fingerprinting typically occurs without the user’s knowledge or consent. Since the release of iOS 7, Apple has restricted apps from gathering data about the hardware of devices in order to reduce the effects of fingerprinting for its users. [34] Although Apple’s changes have reduced some of the data collected for fingerprinting, there are still many ways that other companies and advertisers work around such limitations. [35]

References

- ↑ If an app asks to track your activity. Apple Support. (2022, May 10). Retrieved February 10, 2023, from https://support.apple.com/en-us/HT212025#:~:text=App%20Tracking%20Transparency%20allows%20you,or%20sharing%20with%20data%20brokers

- ↑ If an app asks to track your activity. Apple Support. (2022, May 10). Retrieved January 25, 2023, from https://support.apple.com/en-us/HT212025#:~:text=App%20Tracking%20Transparency%20allows%20you,or%20sharing%20with%20data%20brokers.

- ↑ Privacy - features. Apple. (n.d.). Retrieved January 25, 2023, from https://www.apple.com/privacy/features/

- ↑ Koetsier, J. (2022, October 12). Apple's att burned facebook bad. google's privacy sandbox is a kiss in comparison. Forbes. Retrieved January 26, 2023, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/johnkoetsier/2022/02/19/apples-att-burned-facebook-bad-googles-privacy-sandbox-is-a-kiss-in-comparison/?sh=3f7cec8f382d

- ↑ What is IDFA and Apple IDFA is important? Adjust. (n.d.). Retrieved January 22, 2023, from https://www.adjust.com/glossary/idfa/

- ↑ What IDFA Privacy Changes Mean for Digital Advertising on IOS Devices Epsilon. (n.d.). Retrieved January 22, 2023, from https://www.epsilon.com/us/insights/trends/idfa

- ↑ Speaking up for small businesses. Meta. (2021, June 30). Retrieved February 9, 2023, from https://about.fb.com/news/2020/12/speaking-up-for-small-businesses/

- ↑ Speaking up for small businesses. Meta. (2021, June 30). Retrieved February 9, 2023, from https://about.fb.com/news/2020/12/speaking-up-for-small-businesses/

- ↑ Megan Graham. (2020, December 17). Facebook blasts Apple in new ads over iphone privacy change. CNBC. Retrieved January 27, 2023, from https://www.cnbc.com/2020/12/16/facebook-blasts-apple-in-new-ads-over-iphone-privacy-change-.html

- ↑ O'Flaherty, K. (2022, November 8). Apple's privacy features will cost facebook $12 billion. Forbes. Retrieved January 27, 2023, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/kateoflahertyuk/2022/04/23/apple-just-issued-stunning-12-billion-blow-to-facebook/?sh=25f6b5561907

- ↑ Gilbert, B. (n.d.). Facebook blames Apple after a historically bad quarter, saying iphone privacy changes will cost it $10 billion. Business Insider. Retrieved February 9, 2023, from https://www.businessinsider.com/facebook-blames-apple-10-billion-loss-ad-privacy-warning-2022-2

- ↑ Kharpal, A. (2022, December 23). Facebook parent meta agrees to pay $725 million to settle privacy lawsuit. CNBC. Retrieved February 9, 2023, from https://www.cnbc.com/2022/12/23/facebook-parent-meta-agrees-to-pay-725-million-to-settle-privacy-lawsuit-prompted-by-cambridge-analytica-scandal.html

- ↑ O'Flaherty, K. (2022, September 24). Facebook sued for violating Apple's iPhone Privacy Rules. Forbes. Retrieved February 9, 2023, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/kateoflahertyuk/2022/09/22/facebook-keeps-giving-users-more-reasons-to-delete-their-accounts/?sh=28ac91ab358a

- ↑ Technology for a more private web. The privacy Sandbox. (n.d.). Retrieved February 9, 2023, from https://privacysandbox.com/

- ↑ Chavez, A. (2022, February 16). Introducing the Privacy Sandbox on Android. Google. Retrieved February 9, 2023, from https://blog.google/products/android/introducing-privacy-sandbox-android/

- ↑ Twitter. (n.d.). Tracking on IOS 14.5+. Twitter. Retrieved February 9, 2023, from https://help.twitter.com/en/safety-and-security/about-ios-tracking

- ↑ Twitter. (n.d.). Twitter privacy policy. Twitter. Retrieved February 9, 2023, from https://twitter.com/en/privacy#twitter-privacy-2

- ↑ Twitter. (n.d.). Twitter and Att - Resource Center. Twitter. Retrieved February 9, 2023, from https://business.twitter.com/en/help/overview/twitter-ios14-resource-center.html

- ↑ Tsalis, N., Mylonas, A., Nisioti, A., Gritzalis, D., & Katos, V. (2017). Exploring the protection of private browsing in desktop browsers. Computers & Security, 67, 181–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cose.2017.03.006

- ↑ Wu, Y., Gupta, P., Wei, M., Acar, Y., Fahl, S., & Ur, B. (2018). Your secrets are safe. Proceedings of the 2018 World Wide Web Conference on World Wide Web - WWW '18. https://doi.org/10.1145/3178876.3186088

- ↑ Smith, E.J. (2010). iPhone Applications & Privacy Issues: An Analysis of Application Transmission of iPhone Unique Device Identifiers (UDIDs).

- ↑ Michael, K., & Clarke, R. (2013). Location and tracking of mobile devices: überveillance stalks the streets. Computer Law & Security Review, 29(3), 216–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clsr.2013.03.004

- ↑ Kelion, L. (2015, September 8). Apple brings ad-blocker extensions to Safari on iPhones. BBC News. Retrieved January 27, 2023, from https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-34173732

- ↑ Apple Intelligent Tracking Prevention (ITP) 2.X. How Does Target Handle Apple ITP Support? (n.d.). Retrieved January 27, 2023, from https://developer.adobe.com/target/before-implement/privacy/apple-itp-2x/

- ↑ Merzdovnik, G., Huber, M., Buhov, D., Nikiforakis, N., Neuner, S., Schmiedecker, M., & Weippl, E. (2017). Block me if you can: A large-scale study of tracker-blocking tools. 2017 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy (EuroS&P). https://doi.org/10.1109/eurosp.2017.26

- ↑ Koetsier, J. (2021, June 28). Apple just crippled IDFA, sending an $80 billion industry into upheaval. Forbes. Retrieved January 27, 2023, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/johnkoetsier/2020/06/24/apple-just-made-idfa-opt-in-sending-an-80-billion-industry-into-upheaval/?sh=4a235e57712c

- ↑ Apple advances its privacy leadership with IOS 15, ipados 15, macOS Monterey, and watchos 8. Apple Newsroom. (2023, February 3). Retrieved February 9, 2023, from https://www.apple.com/newsroom/2021/06/apple-advances-its-privacy-leadership-with-ios-15-ipados-15-macos-monterey-and-watchos-8/

- ↑ Kollnig, K., Shuba, A., Van Kleek, M., Binns, R., & Shadbolt, N. (2022). Goodbye tracking? impact of IOS app tracking transparency and privacy labels. 2022 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency. https://doi.org/10.1145/3531146.3533116

- ↑ Kollnig, K., Shuba, A., Van Kleek, M., Binns, R., & Shadbolt, N. (2022). Goodbye tracking? impact of IOS app tracking transparency and privacy labels. 2022 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency. https://doi.org/10.1145/3531146.3533116

- ↑ What is IDFA and Apple IDFA is important? Adjust. (n.d.). Retrieved January 22, 2023, from https://www.adjust.com/glossary/idfa/

- ↑ Apple Inc. (n.d.). User Privacy and Data Use - App Store. Apple Store. Retrieved January 22, 2023, from https://developer.apple.com/app-store/user-privacy-and-data-use/

- ↑ SKAdNetwork. Apple Developer Documentation. (n.d.). Retrieved January 25, 2023, from https://developer.apple.com/documentation/storekit/skadnetwork

- ↑ What is fingerprinting and why you should block it. Mozilla. (n.d.). Retrieved February 9, 2023, from https://www.mozilla.org/en-US/firefox/features/block-fingerprinting/

- ↑ Kurtz, A., Gascon, H., Becker, T., Rieck, K., & Freiling, F. (2015). Fingerprinting mobile devices using personalized configurations. Proceedings on Privacy Enhancing Technologies, 2016(1), 4–19. https://doi.org/10.1515/popets-2015-0027

- ↑ Gómez-Boix, A., Frey, D., Bromberg, Y.-D., & Baudry, B. (2019). A collaborative strategy for mitigating tracking through browser fingerprinting. Proceedings of the 6th ACM Workshop on Moving Target Defense. https://doi.org/10.1145/3338468.3356828