Virtual Private Network

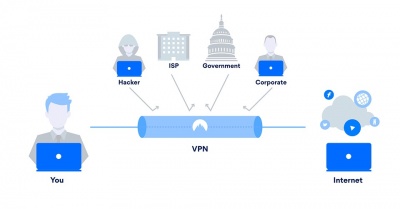

A virtual private network (VPN) is a technology used to create a safe and private connection over a public network.[1] This is achieved by controlling internet traffic between the user's computer and the destination so the location of the user's computer is hidden or it appears that they are working from somewhere other than their true location.[2] VPNs can be used by both businesses and individuals.

Contents

Types of VPNs

Different types of VPNs come from varying strategies of redirecting and masking internet traffic. There are two primary types of VPNs: Site-to-Site and Remote Access.[3]

Site-to-Site

A Site-to-Site VPN, also called a Router-to-Router VPN, occurs when at least one user's network connects to another.[3] According to cybersecurity company Fortinet, these types of VPNs are often found in business settings. These routers connect to essentially form one large network comprised of local networks.[4] This allows someone on one of the local connections to access information from any of the other local networks connected to the VPN.

Remote Access

With a Remote Access VPN, rather than connecting to another router, the user connects securely to a remote network.[5] By using a remote access VPN, an encrypted "tunnel" is created from the user's location to the VPN destination. This destination is determined by the creator of the private network being accessed, and some VPNs allow the user to choose their destination.[2]

Uses

Access Remote Sites

Using a remote access VPN, users from across the globe can access a singular private network.[6] At the University of Michigan, a VPN is used to allow students to access the University's encrypted data when not on the campus internet. This allows students to remotely access information stored at the university, such as databases, or to take advantage of network protection provided through the university.[7] Throughout the Covid-19 pandemic, companies have relied on VPNs to grant employees access to servers, internal applications, and data hosted on-site. These actions were taken to limit the exposure of sensitive data.[8][9]

Privacy

As a VPN encrypts the data between the user and the network, it can help keep a user's information private.[8] This functionality is similar to how VPNs are used to access remote sites, as they help a user access data without having to worry about the WiFi network they're connected to.[11] By encrypting the information, the internet provider, government, and others who control the network can see less of what a user is doing online. Not only does this limit what data is collected about the user, but it can also decrease the number of targeted ads and help to hide the user's location.[12]

Access Information From Other Countries

A VPN can also allow a user to access information that is otherwise not available to them by making it appear as if they are located outside of their physical location.

Circumventing Government Censorship

By disguising the IP address that a request comes from, a VPN can help to access sites blocked by the government in the country where the user is located. In China, The Great Firewall is a name given to the censorship of the internet. By using a VPN, Chinese citizens are able to access information that would have otherwise been restricted by their government.[13] This has also allowed Chinese companies to conduct business with overseas partners. As new programs in China seek to control internet usage, some argue that VPNs can be useful tools to avoid these restrictions.[14] China is not the only location where VPNs are used to access blocked content. In Kashmir, people are using VPNs to access social media sites such as WhatsApp or Instagram that have been banned.[15]

Streaming Services

Another common use for a VPN is accessing streaming services that are not available in a given country. Viewers use VPNs to access Netflix libraries with larger content than their home country.[16]

The 5 Eyes, 9 Eyes, and 14 Eyes Agreements

After World War II, the United States and the United Kingdom signed the BRUSA Agreement to share intelligence between the two countries. (The BRUSA Agreement is now known as the UKUSA Agreement.[17] Over time, this agreement grew to include more countries, eventually leading to the 5 Eyes, 9 Eyes, and 14 Eyes agreements (each one involving a different group of countries). As a part of this agreement, any intelligence gained by one country is automatically shared with all other countries in the agreement.[18] Some VPN companies, such as Restore Privacy, highlight this arrangement in support of using their services, claiming that they can help users escape government surveillance and information sharing between countries with these agreements.[19]

Ethical Concerns

Most ethical concerns regarding VPNs come from the commercial side of the technology.

Pirating of Paid Content

Since VPNs can help make a user's web access history a secret from their ISP, VPNs have become popular tools for torrenting copyrighted material. This has resulted in lawsuits from producers who argue that VPN companies promote and facilitate pirating.[20]

Security of a VPN

Using a VPN does not hide the information being sent from everyone, but instead shifts the ability to see the information from the user's internet service provider to the VPN provider.[22] While VPN companies claim that they help protect users, the user is still at the mercy of the company for their security. As an example, NordVPN, a leading provider, got hacked in 2019 and did not disclose the hack for months.[23] Users are led to believe that using a VPN solves all their worries, when in reality their privacy depends on the company they use.

Many users rely on virtual private network services for a number of reasons: to preserve their privacy, circumvent censorship, and access geo-filtered content. [24] The majority of users have limited means to verify the VPN service’s claims to provide these abilities. A 2018 evaluation of 62 commercial VPN providers showed that while the services seem less likely to intercept or tamper with user traffic, many VPNs do leak user traffic through a variety of means. [24] From the study, 5-30% of the VPN vantage points (associated with 10% of the providers studied) appeared to be hosted on servers located in countries other than those advertised to users. [24] Perta et. al. analyzed 14 of the most popular commercial VPN services in 2015 and inspected their internals and infrastructures.[25] They found that the majority of VPN services suffer from IPv6 traffic leakage. A sophisticated DNS hijacking attack would allow all traffic to be transparently captured. [25]

Misleading Advertisements

Several VPN companies have been found to have made misleading claims about their product. In 2019, NordVPN had an advertisement banned in the UK when they made false claims suggesting that users without a VPN are broadcasting their passwords to hackers on public WiFi.[26] The Advertising Standards Agency found that the ad made viewers believe that public networks are inherently insecure when this is not true. Other companies have claimed that they keep no logs on user information, but independent investigations have found that several of these companies, including UFO VPN did keep logs.[27]. These misleading claims can be difficult to verify, but by claiming that people are always at risk such as how NordVPN did, and offering a solution, these companies prey on those who don't understand how VPNs work.

See Also

References

- ↑ Gewirtz, David, and Rae Hodge. “Best VPN service of 2021.” CNN, 19 Mar. 2021, www.cnet.com/news/best-vpn/. Accessed 25 Mar. 2021.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Symanovich, Steve. "What is a VPN?" Norton, 14 Jan. 2021, us.norton.com/internetsecurity-privacy-what-is-a-vpn.html. Accessed 8 Apr. 2021.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Types of Virtual Private Network (VPN) and its Protocols." Geeks for Geeks, 10 Apr. 2019, www.geeksforgeeks.org/types-of-virtual-private-network-vpn-and-its-protocols/. Accessed 8 Apr. 2021.

- ↑ "What is a Site-to-Site VPN?" Fortinet, www.fortinet.com/resources/cyberglossary/what-is-site-to-site-vpn. Accessed 8 Apr. 2021.

- ↑ “Different Types of VPNs and When to Use Them.” VPNMentor, www.vpnmentor.com/blog/different-types-of-vpns-and-when-to-use-them/. Accessed 12 Mar 2021.

- ↑ “Virtual private networks.” IEEE Potentials, vol. 20, no. 1, 2001, pp. 11-15, doi:10.1109/45.913204. Accessed 12 Mar. 2021.

- ↑ “Virtual Private Network (VPN).” Information and Technology Services, University of Michigan, its.umich.edu/enterprise/wifi-networks/vpn. Accessed 12 Mar. 2021.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 “What is a business VPN?” Cloudflare, www.cloudflare.com/learning/access-management/what-is-a-business-vpn/. Accessed 12 Mar. 2021.

- ↑ “Why Companies Are Turning To VPNs During The Coronavirus Outbreak.” OpenVPN, openvpn.net/why-companies-are-turning-to-vpns-during-the-coronavirus-outbreak. Accessed 12 Mar. 2021.

- ↑ “The ultimate guide to VPN encryption, protocols, and ciphers.” ATT, 31 July 2019, cybersecurity.att.com/blogs/security-essentials/the-ultimate-guide-to-vpn-encryption-protocols-and-ciphers. Accessed 25 Mar. 2021.

- ↑ Levin, Benjamin. “A VPN is vital when working from home, so here’s everything you need to know.” CNN, 17 Sept. 2020, www.cnn.com/2020/09/17/cnn-underscored/how-to-setup-a-vpn. Accessed 12 Mar. 2021.

- ↑ “What is a VPN.” Cloudflare, www.cloudflare.com/learning/access-management/what-is-a-vpn/. Accessed 12 Mar. 2021.

- ↑ Economy, Elizabeth C. “The great firewall of China: Xi Jinping’s internet shutdown.” The Guardian, 29 June 2018, www.theguardian.com/news/2018/jun/29/the-great-firewall-of-china-xi-jinpings-internet-shutdown. Accessed 12 Mar. 2021.

- ↑ Shanghai, Liza Linin and Josh Chin. "China’s VPN Crackdown Weighs on Foreign Companies There." The Wall Street Journal, 2017 Aug. 2, www.wsj.com/articles/chinas-vpn-crackdown-weighs-on-foreign-companies-there-1501680195. Accessed 8 Apr. 2021.

- ↑ Bukhari, Fayaz. “India cracks down on use of VPNs in Kashmir to get around social media ban.” Reuters, 19 Feb. 2020, www.reuters.com/article/us-india-kashmir-internet/india-cracks-down-on-use-of-vpns-in-kashmir-to-get-around-social-media-ban-idUSKBN20D0LT. Accessed 12 Mar. 2021.

- ↑ Hodge, Rae. “VPN use surges during the coronavirus lockdown, but so do security risks.” CNET, 23 Apr. 2020, www.cnet.com/news/vpn-use-surges-during-the-coronavirus-lockdown-but-so-do-security-risks/. Accessed 12 Mar. 2021.

- ↑ "UKUSA Agreement Release." National Security Agency Central Security Service, www.nsa.gov/news-features/declassified-documents/ukusa/. Accessed 1 Apr. 2021.

- ↑ "Five Eyes." Privacy International, privacyinternational.org/learn/five-eyes. Accessed 8 Apr. 2021.

- ↑ Taylor, Sven. "Five Eyes, Nine Eyes, 14 Eyes – Explained." Restore Privacy, 3 Sep. 2020, restoreprivacy.com/5-eyes-9-eyes-14-eyes/. Accessed 8 Apr. 2021.

- ↑ Sharma, Mayank. “This top VPN is being sued by filmmakers.” Future US, 11 Mar 2021, Accessed 12 Mar 2021.

- ↑ “Popcorn Time VPN.” LiquidVPN, Accessed 25 Mar 2021.

- ↑ Scott, Tom. “This Video Is Sponsored By ███ VPN.” YouTube, 28 Oct 2019, Accessed 12 Mar 2021.

- ↑ Whittaker, Zack. “NordVPN confirms it was hacked.” TechCrunched, 21 Oct 2019, Accessed 12 Mar 2021.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Khan, M. T., DeBlasio, J., Voelker, G. M., Snoeren, A. C., Kanich, C., & Vallina-Rodriguez, N. (2018, October). An empirical analysis of the commercial vpn ecosystem. In Proceedings of the Internet Measurement Conference 2018 (pp. 443-456).

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Perta, V. C., Barbera, M., Tyson, G., Haddadi, H., & Mei, A. (2015). A glance through the VPN looking glass: IPv6 leakage and DNS hijacking in commercial VPN clients.

- ↑ Smith, Adam. “NordVPN Ad Banned for Exaggerating Threat of Public Wi-Fi.” PCMag, 1 May 2019, Accessed 12 Mar 2021.

- ↑ Bischoff, Paul. ““Zero logs” VPN exposes millions of logs including user passwords, claims data is anonymous.” Comparitech, 21 July 2020, Accessed 12 Mar 2021.