Theranos

Theranos, founded by Elizabeth Holmes in 2003, was an American privately held corporation in Silicon Valley. [1] [2] The health technology startup’s mission was to revolutionize blood testing by claiming to have developed a technology that could test for more than 200 health conditions using a single drop of blood from a fingerprint. However, these claims were proven false. [3]

The company raised more than $700 million dollars from venture capitalists and private investors such as Oracle founder Larry Ellison and media mogul Rupert Murdoch. [4] The value of the company continued to grow from 2003 to 2014 when it reached its highest valuation of $10 billion dollars. However, in 2015 a journalist from The Wall Street Journal, John Carreyrou, raised questions about the legitimacy and validity of Theranos’s technology. [5] Thernaos began to feel legal heat from investors and medical authorities such as the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).[6] Major partners such as Walgreen began to back out of agreements as the technology continued to fall short and more questions surfaced. By June of 2016 Holmes, a 50% shareholder, personal net worth dropped from $4.5 billion to almost nothing. The company ceased operation and was dissolved on September 4, 2018. [7]

Holmes and former president of the company Ramesh Balwani were indicted by the United States Attorney for the Northern District of California on multiple wire fraud and conspiracy counts. [8] The trial started on August 21, 2021 and Holmes was found guilty on 4 of the 11 counts on January 3, 2022. [9]

Contents

History

Elizabeth Holmes

Elizabth Holmes, born February 3, 1984, is an American former biotechnology entrepreneur who founded Theranos in 2003 at the age of 19. Holmes was born in Washington, D.C. to her dad Christian Holmes an entrepreneur who started an energy company called Enron then moving to the government agency USAID and her mom Noel, a Congressional committee staffer. [10] The family moved from Washington, D.C. to Houston, Texas when she was a young. [11] At the young age of nine Holmes wrote a letter to her dad saying that she “really want[ed] out of life is to discover something new, something that mankind didn’t know was possible to do." [12] This entrepreneurial spirit was also seen through her starting a business selling coding translation software to Chinese universities. [13]

Holmes attended Stanford University in 2002 where she studied chemical engineering and worked in a laboratory as a student researcher in the School of Engineering. [14] At the end of freshman year, she worked in the Genome Institute of Singapore; at the lab she collected samples of blood with syringes to test for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV-1).[15] Seeing the great amount of blood needed to test for this disease prompted Holmes to take action and seek to improve blood testing processes. [16]

Founding

While at Stanford University, Elizabeth Holmes came up with the idea of developing a technology in the form of a patch that could adjust the dosage of a drug delivery and notify doctors of variables in patients’ blood. [17] Her goal was to build a company that would make blood tests available directly to consumers and eliminate the need for large needles and tubes of blood. She started developing lab-on-chip technology for blood tests and claimed to have developed a technology that could run more than 200 tests from just a few drops of blood. [18] In 2003, Holmes dropped out of Stanford and founded the company “Real-Time Cures” which later became Theranos, derived from the words “therapy” and “diagnosis”. [19]

Partnerships/Investors

Theranos raised about $1.3 billion in funding over the course of its history. The company first raised money with a $500,000 seed round in June of 2004 led by Draper Fisher Jurvetson, now called Threshold. [20] By 2007, Theranos valuation hit nearly $200 million after three years of fundraising and support from Media mogul Rupert Murdoch and venture capitalist Tim Draper. By 2010, the company was valued at $1 billion and Theranos filed a U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission form stating it had raised $45 million. In 2012, Safeway invested $350 million into creating 800 locations that would offer in-store blood tests. However, this partnership fell through as Theranos missed deadlines and more questions surfaced about the company’s technology. [21]

In 2013, Thernos took a huge step and announces itself and its technology to the public through press releases and publishing a website. This shift to operate publicly created mainstream attention resulting in more partnerships and investors. The Pharmacy giant Walgreens partnered with Theranos, raising $50 million and offering in-store blood tests at more than 40 locations. [22] However this high-profile partnership ended in 2016 when Walgreens sued Theranos after questions were raised about the validity of its tests and alleged a breach of contract. [23]

By 2014, Theranos' value exceeded $9 billion. In the next few years the company continued to grow and announced partnerships with the Cleveland Clinic in March 2015 as well as Capital BlueCross in July 2015. While the company continued to gain attention and raise money, members of the medical community criticized the lack of public research in peer-reviewed medical journals. [24]

Timeline

2003: Holmes drops out of Stanford and founds Theranos

At the young age of 19, Elizabeth Holmes dropped out of Stanford’s School of Engineering and started Theranos. Her goal was to create a test that could detect diseases and health problems with the same accuracy as traditional blood tests but with only a few drops from a finger prick. [25]

2004-2010: Theranos grows with early funding

By 2004, Theranos was valued at $30 million and Holmes had raised at least $6.9 million dollars. [26] With this strong start, Thernaos continued to gain investors as well as mainstream attention. By 2007, Theranos’s value grew to $197 million and raised another $43.2 million. The startup continued to fundraise for three years and by 2010 the company was valued above $1 billion. [27]

September 2013: Theranos partners with Walgreens and goes public

With the initial fundraising and research out of the public eye, Theranos partners with Walgreens and blood tests are offered to the public in Arizona and California. [28]

2014: Theranos values at over $9 billion while doubts surface

Theranos’s valuation reaches $9 billion dollars, making Holmes worth $4.5 billion with 50% stake in the company and the youngest self-made billionaire. [29] However, suspicions rose in the medical community about the legitimacy and reliability of the technology developed by Theranos with the lack of public research and peer-reviewed medical journals. A New Yorker profile about Holmes describes her explanations of the technology as “comically vague." [30]

July 2015: FDA Approves Theranos herpes simplex virus 1 test

Theranos continues to expand with the FDA approving Theranos’s test for detecting herpes simplex virus 1 and Capital BlueCross choosing Theranos as its main lab work provider. Theranos was not valued at $10 billion dollars. [31]

October 15, 2015: John Carreyrou of the Wall Street Journal publishes scathing article

The Wall Street Journal publishes a series of articles exposing the questions surrounding Theranos’s technology. Carreyrou interviewed ex-employees of Theranos and reported that Theranos had drastically overstated the capabilities of its technology.[32]

November 2015: Safeway partnership ends

The US supermarket conglomerate Safeway worth $350 million dollars fell through when Theranos failed to meet deadlines after Safeway had built testing facilities in over 800 supermarkets. The executives at Safeway did not trust the validity of the Theranos product. [33]

January 2016: CMS letter released warning about patient health threat

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) announces that after an inspection of Theranos’s California lab deficient practices were uncovered that pose immediate jeopardy to patient health and safety. [34]

October 2016: One of Theranos’s largest investors sues and Theranos closes it medical lab operations

One of the largest investors, Partner Fund Management (PFM) , accused the company of securities fraud. [35] Theranos also closes its medical lab operations with continued scrutiny and shrinks its workforce by more than 40%.[36]

March 2018: Theranos is charged with massive fraud

The Securities and Exchange Commission charged Holmes and Balwani with civil-securities fraud; “raising more than $700 million from investors through an elaborate, years-long fraud in which they exaggerated or made false statements about the company’s technology, business, and financial performance.” [37]

June 2018: Holmes and Balwani indicted

A federal grand jury indicted Holmes and Balwani with 11 criminal charges. Holmes stepped down as CEO but remained on the company board. [38]

September 2018: The end of Theranos

Theranos was forced to close as it was unable to find a buyer. The company said they would pay off its creditors with its remaining funds. [39]

September 8, 2021: Trial begins [40]

Criminal Investigation

Criminal Proceedings

On June 15, 2018, Holmes and Balwani were indicted on two counts of conspiracy to commit wire fraud and nine counts of wire fraud. The charges derived from allegations that both engaged in a multi-million-dollar scheme to defraud investors as well as doctors and patients. [41] Both Holmes and Balwani pleaded not guilty. [42] The trial was delayed by the COVID-19 pandemic as well as the birth of her child; it began on December 7, 2021 in San Jose, California. [43]

The trail lasted for 11 weeks as fascination was sprawling outside of the courtroom. During the trial, led by prosecutor John Bostic, federal prosecutors called 29 witnesses to testify which included past Theranos employees, retail executives, as well as a former US Defense Secretary. [44] In the closing arguments, the prosecution alleged that faced with a business running out of money, Holmes “chose fraud” rather than “failure.” [45]

Holmes testified for seven days and her testimony was focused on her belief in the company’s technology as well as pointing fingers at others, specifically her ex-boyfriend Balwani. [46] She testified that her relationship with Balwani was abusive and that he tried to control all aspects of her life. Balwani denies all of these allegations. [47]

The jury deliberated for seven days. [48]

Jury Verdict

The jury convicted Holmes of the investor wire fraud conspiracy count and three wire fraud counts relating to the scheme to defraud investors. [49] The jury acquitted Holmes of the patient-related conspiracy wire fraud count and three other wire fraud counts. Additionally, one count of wire fraud was dismissed during the trail relating to one count of wire fraud. The last three investor fraud-related counts were dismissed as the jury could not reach a unambiguous verdict. [50]

Elizabeth Holmes faces a maximum sentence of 20 years in prison and a fine of $250,000 plus restitution. [51]

While the Theranos trial has come to an end, this case has caused many questions to surface about the ethics of technology entrepreneurship and the systems that are in place to prevent another Theranos.

Technology and Products

Theranos claimed to have created a technology that could automate blood tests with just a few drops of blood through the blood collection vessel called the “nanotainer” and the analysis machine, the “Edison.” [52] Typically blood tests require a trip to a doctor’s office or lab to draw a significant amount of blood that then goes through a complicated process of testing with different chemicals and pieces of equipment. [53] However, Holmes claimed to have created a technology that can test just a few drops of blood from a finger print and be analyzed in just a few hours. [54]

The Edison was the system that analyzed the blood and could communicate with the Internet to receive instructions on what tests to run and then communicate back the results. [55] The device was a black rectangle about the size of a desktop printer with a screen on the front; Holmes wanted the Edison to look like the iPhone screen and for the casing to look like a Mac. [56] This technology was criticized by the medical community for not being peer reviewed while Theranos claimed to have data backing the accuracy and reliability of the technology and tests. [57]

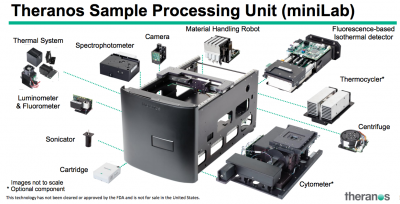

In 2016, Theranos announced a new technology named “miniLab” at the American Association for Clinical Chemistry annual meeting. This robotic capillary blood testing device was allegedly capable of carrying out a range of tests from a few drops of blood. [58]

Ethical Implications

Misinformation

Misinformation is incorrect or misleading information. [59] Today, in modern high-choice media democratic societies, exposure to misinformation can be harmful and result in negative repercussions for governance and trust in news and journalism. [60] In the case of Theranos, the company spread misinformation in order to secure millions of dollars in investments. According to the SEC, in order to secure a deal with Walgreens, Theranos created a fake demonstration of the technology and Holmes told her employees to put Theranos’s equipment in the room where blood samples were collected but instead of using Theranos machines, employees secretly ran tests on an outside lab equipment. [61]

Additionally, during the Theranos trial, Daniel Edlin, a senior product manager at Theranos, testified that Theranos hid failures or didn’t analyze the blood during the demonstrations. He also stated that the company would remove abnormal results before sending reports to investors. For example, one of the biggest investors Rupert Murdoch had his blood drawn in a demonstration in January 2015; his results had some issues and Edlin was instructed to remove these results before sending the report to Murdoch. [62]

Misinformation also impacted patients who were given blood test results that were inaccurate, causing many patients harm due to misdiagnosis. [63] A woman identified as L.M. was diagnosed with a thyroid condition called Hashimoto’s disease after getting a Theranos blood test. The diagnosis resulted in changes to her lifestyle, more medical appointments, and taking new medication that she did not need. [64] Another patient Erin Tompkins was inaccurately diagnosed with HIV, a serious virus that attacks a person’s immune system. [65] [66] Mr. Hammons, a retired marketer from Arizona, after having a heart surgery was told that Theranos had corrected an incorrect result showing that his blood takes more than six times longer than normal to clot. After five different visits to Theranos and extremely varied results, his doctor told him to stop taking his blood thinner. [67] Numerous examples of investor and patient misinformation were disputed during the trial, the jury acquitted Holmes of the patient-related conspiracy fraud counts. [68]

Ethics in Entrepreneurship and Business Culture

Ethical Entrepreneurship is “the journey of intentionally creating a constructive organizational culture.” [69] Recently, businesses have been increasing their investment and focus on the impact they are making to the world. Companies have to think about and prioritize the need for ethics when building company culture for the longevity and success of their business in the long term. [70] The core of entrepreneurship is “a vision of something not yet in the world.” [71] It is argued that in order to be successful when building a business, entrepreneurs have to block out the negativity and hate in order to be successful. However, organizations must create a healthy work culture as it is a vital ethical component and holds leaders accountable. [72] Many ex-Theranos employees have spoken out about the toxic culture of Theranos. Holmes organized the company so that all employees were purposely siloed. [73] Employees were not supposed to communicate with each other about their work and were told to not reveal the company name on social media. A former employee Adam Vollmer said “It was a complete distrust for the organization that she'd built under her.” Another employee Ana Arriola said “She [Holmes] did not want to hear other people's opinions, … She wanted positive results. I think that anyone who told Elizabeth no and disagreed with her perspective and point of view, you were immediately terminated... It was just a very unusual environment.” [74]

This toxic culture of Theranos prompted two former employees Erika Cheung and Tyler Schultz to create an organization called Ethics in Entrepreneurship with the mission of preventing other health startups from experiencing what they did. [75] At the Manova Global Summit on the Future of Health in Minneapolis in 2019 Cheng voiced that “We’re all here because we want to make an impact and we want to do good and we have good intentions, but making sure you have that strong vision and figuring out how to maintain that” is challenging, She continued by saying that “you have to figure out how to stick to those morals and standards and values despite the chaos.” [76] Cheung and Schultz have come up with a handful of basics for entrepreneurial ethics for almost any company, discretion from investors, be proactive, consider realigning incentives, think before investing, and create a culture of healthy disagreement. [77] Both Cheung and Schultz stated that they think Holmes should go to jail. [78]

Rise and Impact

The question has been raised by many people in the tech industry about what led to Thernaos and what impact it will have on the start-up and medical technology industries. [79] As stated by John Carreyou, the whistleblowers on the Theranos case, “Theranos was one of the most epic failures in corporate governance in the annals of American capitalism.” He explains how the culture of Silicon Valley, specifically the mantras “fake it until you make it” and “fail fast,” created the environment for Theranos to occur. [80] Additionally, there was a gender factor because in the tech world there was a desire for a female entrepreneur to succeed by the likes of Steve Jobs or Mark Zuckerberg. [81] On top of that there were also no checks or balances when it came to Theranos. For example Holmes had 99% of total voting rights so the company’s board, made up of big names such as the Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis, had no influence. [82] There was the perception that this prestigious board created legitimacy, however the board had no say in how the business was run. Theranos also took advantage of a regulatory loophole by performing laboratory-developed tests that did not fall under the Food and Drug Administration or other health agencies. [83] Therefore, no one was policing the business’s processes or offerings. There were also no peer reviews for the technology that Theranos was creating. [84] All of these factors allowed for Elizabeth Holmes to defraud investors and create a billion dollar company that was based on false information and technology. [85]

As for the impact, some say that the Theranos story shines a light on the important distinction of what is at stake when it comes to entrepreneurship in different industries. [86] Getting into industries where there is a public health impact such as self-driving cars and medicine, “you can’t really just iterate and debug as you’re going. You have to get your product working first.” [87] Entrepreneurs and investors, as well as people in every industry have a responsibility to do their research and ensure that the products and ideas coming to market are legitimate. [88] Ellen Kreitzberg, a law professor at Santa Clara University, argues that this trial result sends a message to CEOs in Silicon Valley that “there are consequences in overstepping the bounds."[89] However, experts outside of Silicon Valley argue that it is unlikely that there will be a “dramatic revelation or change in the behavior [in Silicon Valley].” [90] UC Berkeley professor Jennifer Chatman said that “I think we would all like to believe that there will be vicarious learning, that it would reduce the amount of pushing the envelope in terms of ethical behavior and integrity,... that’s not what I think is going to happen.” [91] Not only do some experts believe that there will be no learning or change from Theranos, but some believe that it will happen again. Columbia Business School professor Len Sherman stated that he sees the trail as being “not only not unique, it's just this is the way business is being done, and we're gonna see it again.”[92]

References

- ↑ U.S. v. Elizabeth Holmes, et al.. The United States Department of Justice. (2022, January 5). Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://www.justice.gov/usao-ndca/us-v-elizabeth-holmes-et-al#:~:text=Jury%20Verdict&text=The%20jury%20acquitted%20Holmes%20of,three%20investor%20fraud%2Drelated%20counts

- ↑ Avery Hartmans, P. L. (2022, January 4). The rise and fall of Elizabeth Holmes, the Theranos founder who went from being a Silicon Valley Star to being found guilty of wire fraud and conspiracy. Business Insider. Retrieved January 26, 2022, from https://www.businessinsider.com/theranos-founder-ceo-elizabeth-holmes-life-story-bio-2018-4

- ↑ Tun, Z. T. (2022, January 4). A timeline of Theranos's troubles. Investopedia. Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://www.investopedia.com/articles/investing/020116/theranos-fallen-unicorn.asp#:~:text=Theranos%20Inc.%2C%20a%20consumer%20healthcare,revolutionize%20the%20blood%2Dtesting%20industry.&text=The%20SEC%20charged%20Theranos%2C%20its,%22Sunny%22%20Balwani%20with%20fraud.

- ↑ O'Brian, S. A., & Board Members Who Were Involved In The Company. (n.d.). Elizabeth Holmes surrounded Theranos with powerful people. CNNMoney. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://money.cnn.com/2018/03/15/technology/elizabeth-holmes-theranos/index.html

- ↑ Tun, Z. T. (2022, January 4). A timeline of Theranos's troubles. Investopedia. Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://www.investopedia.com/articles/investing/020116/theranos-fallen-unicorn.asp#:~:text=Theranos%20Inc.%2C%20a%20consumer%20healthcare,revolutionize%20the%20blood%2Dtesting%20industry.&text=The%20SEC%20charged%20Theranos%2C%20its,%22Sunny%22%20Balwani%20with%20fraud.

- ↑ Tun, Z. T. (2022, January 4). A timeline of Theranos's troubles. Investopedia. Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://www.investopedia.com/articles/investing/020116/theranos-fallen-unicorn.asp#:~:text=Theranos%20Inc.%2C%20a%20consumer%20healthcare,revolutionize%20the%20blood%2Dtesting%20industry.&text=The%20SEC%20charged%20Theranos%2C%20its,%22Sunny%22%20Balwani%20with%20fraud.

- ↑ Weisul, K. (2015, September 16). How Elizabeth Holmes' billion-dollar drug company, Theranos, won by playing The long game. Inc.com. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://www.inc.com/magazine/201510/kimberly-weisul/the-longest-game.html

- ↑ U.S. v. Elizabeth Holmes, et al.. The United States Department of Justice. (2022, January 5). Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://www.justice.gov/usao-ndca/us-v-elizabeth-holmes-et-al#:~:text=Jury%20Verdict&text=The%20jury%20acquitted%20Holmes%20of,three%20investor%20fraud%2Drelated%20counts.

- ↑ U.S. v. Elizabeth Holmes, et al.. The United States Department of Justice. (2022, January 5). Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://www.justice.gov/usao-ndca/us-v-elizabeth-holmes-et-al#:~:text=Jury%20Verdict&text=The%20jury%20acquitted%20Holmes%20of,three%20investor%20fraud%2Drelated%20counts.

- ↑ Avery Hartmans, P. L. (2022, January 4). The rise and fall of Elizabeth Holmes, the Theranos founder who went from being a Silicon Valley Star to being found guilty of wire fraud and conspiracy. Business Insider. Retrieved January 26, 2022, from https://www.businessinsider.com/theranos-founder-ceo-elizabeth-holmes-life-story-bio-2018-4

- ↑ Maranzani, B. (2020, May 13). Elizabeth Holmes. Biography.com. Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://www.biography.com/business-figure/elizabeth-holmes

- ↑ Thomas, D. (2022, January 4). Theranos scandal: Who is Elizabeth Holmes and why was she on trial? BBC News. Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://www.bbc.com/news/business-58336998

- ↑ Maranzani, B. (2020, May 13). Elizabeth Holmes. Biography.com. Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://www.biography.com/business-figure/elizabeth-holmes

- ↑ Waltz, E. (2022, January 4). Elizabeth Holmes verdict: Researchers share lessons for science. Nature News.

- ↑ Griffin, O. H. (2020). Promises, deceit and white-collar criminality within the Theranos scandal. Journal of White Collar and Corporate Crime. https://doi.org/10.1177/2631309x20953832

- ↑ Griffin, O. H. (2020). Promises, deceit and white-collar criminality within the Theranos scandal. Journal of White Collar and Corporate Crime. https://doi.org/10.1177/2631309x20953832

- ↑ Weisul, K. (2015, September 16). How Elizabeth Holmes' billion-dollar drug company, Theranos, won by playing The long game. Inc.com. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://www.inc.com/magazine/201510/kimberly-weisul/the-longest-game.html

- ↑ Waltz, E. (2022). Elizabeth Holmes verdict: Researchers share lessons for science. Nature, 601(7892), 173–174. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-022-00006-9

- ↑ Pharmacy Times. (2021, March 4). Bringing painless blood testing to the pharmacy. Pharmacy Times. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://www.pharmacytimes.com/view/bringing-painless-blood-testing-to-the-pharmacy

- ↑ Kunthara, S. (2021, September 17). A closer look at Theranos' big-name investors, partners and board as Elizabeth Holmes' criminal trial begins. Crunchbase News. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://news.crunchbase.com/news/theranos-elizabeth-holmes-trial-investors-board/

- ↑ Wasserman, E. (2015, November 11). Safeway severs ties with Theranos as $350m deal collapses. FierceBiotech. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://www.fiercebiotech.com/medical-devices/safeway-severs-ties-theranos-as-350m-deal-collapses

- ↑ Kunthara, S. (2021, September 14). A closer look at Theranos' big-name investors, partners and board as Elizabeth Holmes' criminal trial begins. NewsBreak. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://www.newsbreak.com/news/2371072417137/a-closer-look-at-theranos-big-name-investors-partners-and-board-as-elizabeth-holmes-criminal-trial-begins

- ↑ Kunthara, S. (2021, September 17). A closer look at Theranos' big-name investors, partners and board as Elizabeth Holmes' criminal trial begins. Crunchbase News. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://news.crunchbase.com/news/theranos-elizabeth-holmes-trial-investors-board/

- ↑ Kunthara, S. (2021, September 17). A closer look at Theranos' big-name investors, partners and board as Elizabeth Holmes' criminal trial begins. Crunchbase News. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://news.crunchbase.com/news/theranos-elizabeth-holmes-trial-investors-board/

- ↑ Randazzo, S. (2021, September 13). A theranos timeline: The downfall of Elizabeth Holmes, a Silicon Valley Superstar. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://www.wsj.com/articles/a-theranos-timeline-the-downfall-of-elizabeth-holmes-a-silicon-valley-superstar-11631576110

- ↑ Randazzo, S. (2021, September 13). A theranos timeline: The downfall of Elizabeth Holmes, a Silicon Valley Superstar. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://www.wsj.com/articles/a-theranos-timeline-the-downfall-of-elizabeth-holmes-a-silicon-valley-superstar-11631576110

- ↑ Randazzo, S. (2021, September 13). A theranos timeline: The downfall of Elizabeth Holmes, a Silicon Valley Superstar. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://www.wsj.com/articles/a-theranos-timeline-the-downfall-of-elizabeth-holmes-a-silicon-valley-superstar-11631576110

- ↑ Kent, C., team, the M. D. N., Chloe Kent NULL, Kent, C., & Null. (2019, July 4). Theranos timeline: Where did it all go wrong? Medical Device Network. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://www.medicaldevice-network.com/features/theranos-failure-timeline/

- ↑ Kent, C., team, the M. D. N., Chloe Kent NULL, Kent, C., & Null. (2019, July 4). Theranos timeline: Where did it all go wrong? Medical Device Network. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://www.medicaldevice-network.com/features/theranos-failure-timeline/

- ↑ Randazzo, S. (2021, September 13). A theranos timeline: The downfall of Elizabeth Holmes, a Silicon Valley Superstar. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://www.wsj.com/articles/a-theranos-timeline-the-downfall-of-elizabeth-holmes-a-silicon-valley-superstar-11631576110

- ↑ Johnson, C. Y. (2021, November 25). FDA approves Theranos' $9 finger stick blood test for herpes. The Washington Post. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2015/07/02/fda-approves-theranos-9-finger-stick-bloodtest-for-herpes/

- ↑ Kent, C., team, the M. D. N., Chloe Kent NULL, Kent, C., & Null. (2019, July 4). Theranos timeline: Where did it all go wrong? Medical Device Network. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://www.medicaldevice-network.com/features/theranos-failure-timeline/

- ↑ Kent, C., team, the M. D. N., Chloe Kent NULL, Kent, C., & Null. (2019, July 4). Theranos timeline: Where did it all go wrong? Medical Device Network. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://www.medicaldevice-network.com/features/theranos-failure-timeline/

- ↑ Randazzo, S. (2021, September 13). A theranos timeline: The downfall of Elizabeth Holmes, a Silicon Valley Superstar. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://www.wsj.com/articles/a-theranos-timeline-the-downfall-of-elizabeth-holmes-a-silicon-valley-superstar-11631576110

- ↑ Kent, C., team, the M. D. N., Chloe Kent NULL, Kent, C., & Null. (2019, July 4). Theranos timeline: Where did it all go wrong? Medical Device Network. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://www.medicaldevice-network.com/features/theranos-failure-timeline/

- ↑ Randazzo, S. (2021, September 13). A theranos timeline: The downfall of Elizabeth Holmes, a Silicon Valley Superstar. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://www.wsj.com/articles/a-theranos-timeline-the-downfall-of-elizabeth-holmes-a-silicon-valley-superstar-11631576110

- ↑ Kent, C., team, the M. D. N., Chloe Kent NULL, Kent, C., & Null. (2019, July 4). Theranos timeline: Where did it all go wrong? Medical Device Network. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://www.medicaldevice-network.com/features/theranos-failure-timeline/

- ↑ Kent, C., team, the M. D. N., Chloe Kent NULL, Kent, C., & Null. (2019, July 4). Theranos timeline: Where did it all go wrong? Medical Device Network. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://www.medicaldevice-network.com/features/theranos-failure-timeline/

- ↑ Kent, C., team, the M. D. N., Chloe Kent NULL, Kent, C., & Null. (2019, July 4). Theranos timeline: Where did it all go wrong? Medical Device Network. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://www.medicaldevice-network.com/features/theranos-failure-timeline/

- ↑ Popken, B. (2021, September 8). Theranos' blockbuster trial starts Wednesday. whose story will the jury believe? NBCNews.com. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://www.nbcnews.com/business/business-news/theranos-blockbuster-trial-starts-wednesday-whose-story-will-jury-believe-n1278657

- ↑ U.S. v. Elizabeth Holmes, et al.. The United States Department of Justice. (2022, January 5). Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://www.justice.gov/usao-ndca/us-v-elizabeth-holmes-et-al#:~:text=Jury%20Verdict&text=The%20jury%20acquitted%20Holmes%20of,three%20investor%20fraud%2Drelated%20counts.

- ↑ Mack, E. (2021, November 20). Theranos trial: Prosecution rests, Elizabeth Holmes takes the stand. CNET. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://www.cnet.com/how-to/theranos-trial-elizabeth-holmes-takes-stand-prosecution-rests/

- ↑ O'Brien, S. A. (2022, January 4). Elizabeth Holmes found guilty on four out of 11 federal charges. CNN. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://www.cnn.com/2022/01/03/tech/elizabeth-holmes-verdict/index.html

- ↑ O'Brien, S. A. (2022, January 4). Elizabeth Holmes found guilty on four out of 11 federal charges. CNN. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://www.cnn.com/2022/01/03/tech/elizabeth-holmes-verdict/index.html

- ↑ O'Brien, S. A. (2022, January 4). Elizabeth Holmes found guilty on four out of 11 federal charges. CNN. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://www.cnn.com/2022/01/03/tech/elizabeth-holmes-verdict/index.html

- ↑ O'Brien, S. A. (2022, January 4). Elizabeth Holmes found guilty on four out of 11 federal charges. CNN. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://www.cnn.com/2022/01/03/tech/elizabeth-holmes-verdict/index.html

- ↑ O'Brien, S. A. (2022, January 4). Elizabeth Holmes found guilty on four out of 11 federal charges. CNN. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://www.cnn.com/2022/01/03/tech/elizabeth-holmes-verdict/index.html

- ↑ U.S. v. Elizabeth Holmes, et al.. The United States Department of Justice. (2022, January 5). Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://www.justice.gov/usao-ndca/us-v-elizabeth-holmes-et-al#:~:text=Jury%20Verdict&text=The%20jury%20acquitted%20Holmes%20of,three%20investor%20fraud%2Drelated%20counts.

- ↑ U.S. v. Elizabeth Holmes, et al.. The United States Department of Justice. (2022, January 5). Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://www.justice.gov/usao-ndca/us-v-elizabeth-holmes-et-al#:~:text=Jury%20Verdict&text=The%20jury%20acquitted%20Holmes%20of,three%20investor%20fraud%2Drelated%20counts.

- ↑ U.S. v. Elizabeth Holmes, et al.. The United States Department of Justice. (2022, January 5). Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://www.justice.gov/usao-ndca/us-v-elizabeth-holmes-et-al#:~:text=Jury%20Verdict&text=The%20jury%20acquitted%20Holmes%20of,three%20investor%20fraud%2Drelated%20counts.

- ↑ U.S. v. Elizabeth Holmes, et al.. The United States Department of Justice. (2022, January 5). Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://www.justice.gov/usao-ndca/us-v-elizabeth-holmes-et-al#:~:text=Jury%20Verdict&text=The%20jury%20acquitted%20Holmes%20of,three%20investor%20fraud%2Drelated%20counts.

- ↑ Stieg, C. (n.d.). What exactly was the Theranos Edison Machine Supposed to do? What Was Theranos Edison Machine Supposed To Do Anyway? Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://www.refinery29.com/en-us/2019/03/224904/theranos-edison-machine-blood-test-technology-explained

- ↑ Magazine, S. (2014, March 6). How to run 30 health tests on a single drop of Blood. Smithsonian.com. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://www.smithsonianmag.com/innovation/how-to-run-30-health-tests-on-a-single-drop-of-blood-180949983/

- ↑ Wetsman, N. (2021, December 15). Theranos promised a blood testing revolution - here's what's really possible. The Verge. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://www.theverge.com/22834348/theranos-blood-testing-innovation-drop-holmes

- ↑ Stieg, C. (n.d.). What exactly was the Theranos Edison Machine Supposed to do? What Was Theranos Edison Machine Supposed To Do Anyway? Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://www.refinery29.com/en-us/2019/03/224904/theranos-edison-machine-blood-test-technology-explained

- ↑ Dunn, T., Thompson, V., & Jarvis, R. (n.d.). Ex-Theranos employees describe culture of secrecy at Elizabeth Holmes' startup: ‘The Dropout’ podcast ep. 1. ABC News. Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://abcnews.go.com/Business/theranos-employees-describe-culture-secrecy-elizabeth-holmes-startup/story?id=60544673

- ↑ Stieg, C. (n.d.). What exactly was the Theranos Edison Machine Supposed to do? What Was Theranos Edison Machine Supposed To Do Anyway? Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://www.refinery29.com/en-us/2019/03/224904/theranos-edison-machine-blood-test-technology-explained

- ↑ Abelson, R. (2016, June 1). Elizabeth Holmes, founder of Theranos, falls from highest perch off Forbes list. The New York Times. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/02/business/elizabeth-holmes-founder-of-theranos-falls-from-highest-perch-off-forbes-list.html

- ↑ Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Misinformation definition & meaning. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/misinformation

- ↑ Dan, V., Paris, B., Donovan, J., Hameleers, M., Roozenbeek, J., van der Linden, S., & von Sikorski, C. (2021). Visual mis- and disinformation, social media, and democracy. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 98(3), 641–664. https://doi.org/10.1177/10776990211035395

- ↑ Lee, S. M. (2018, March 14). The seven biggest lies Theranos told. BuzzFeed News. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/stephaniemlee/theranos-elizabeth-holmes-sec-charges

- ↑ Woo, E., & Griffith, E. (2021, October 22). Key takeaways from week 7 of the Elizabeth Holmes trial. The New York Times. Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/22/technology/elizabeth-holmes-trial-takeaways.html

- ↑ Magazine, S. (2014, March 6). How to run 30 health tests on a single drop of Blood. Smithsonian.com. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://www.smithsonianmag.com/innovation/how-to-run-30-health-tests-on-a-single-drop-of-blood-180949983/

- ↑ Bell, B. (2021, December 30). The Theranos trial only cares about the billionaires deceived by Elizabeth Holmes and not the patients. pastemagazine.com. Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://www.pastemagazine.com/tech/theranos-trial-elizabeth-holmes/#:~:text=People%20like%20Brittany%20Gould%2C%20who,witness%20stand%20during%20the%20trial.

- ↑ Bell, B. (2021, December 30). The Theranos trial only cares about the billionaires deceived by Elizabeth Holmes and not the patients. pastemagazine.com. Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://www.pastemagazine.com/tech/theranos-trial-elizabeth-holmes/#:~:text=People%20like%20Brittany%20Gould%2C%20who,witness%20stand%20during%20the%20trial.

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, June 1). About HIV/AIDS. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/whatishiv.html#:~:text=HIV%20(human%20immunodeficiency%20virus)%20is,healthy%20and%20prevent%20HIV%20transmission.

- ↑ Weaver, C. (2016, October 21). Agony, alarm and anger for people hurt by Theranos's botched blood tests. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-patients-hurt-by-theranos-1476973026

- ↑ U.S. v. Elizabeth Holmes, et al.. The United States Department of Justice. (2022, January 5). Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://www.justice.gov/usao-ndca/us-v-/elizabeth-holmes-et-al#:~:text=Jury%20Verdict&text=The%20jury%20acquitted%20Holmes%20of,three%20investor%20fraud%2Drelated%20counts.

- ↑ Moss, P. B. A., & Moss, A. (2019, September 12). Ethical entrepreneurship: Searching for organization-cultural fit. NYU Entrepreneurship. Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://entrepreneur.nyu.edu/blog/2018/09/14/ethical-entrepreneurship/

- ↑ Moss, P. B. A., & Moss, A. (2019, September 12). Ethical entrepreneurship: Searching for organization-cultural fit. NYU Entrepreneurship. Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://entrepreneur.nyu.edu/blog/2018/09/14/ethical-entrepreneurship/

- ↑ Korman, J. (2021, October 21). Council post: Theranos is a cautionary tale that shouldn't dampen enthusiasm for entrepreneurs who dream big. Forbes. Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbescoachescouncil/2021/10/21/theranos-is-a-cautionary-tale-that-shouldnt-dampen-enthusiasm-for-entrepreneurs-who-dream-big/?sh=527308cd1c65

- ↑ Korman, J. (2021, October 21). Council post: Theranos is a cautionary tale that shouldn't dampen enthusiasm for entrepreneurs who dream big. Forbes. Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbescoachescouncil/2021/10/21/theranos-is-a-cautionary-tale-that-shouldnt-dampen-enthusiasm-for-entrepreneurs-who-dream-big/?sh=527308cd1c65

- ↑ Dunn, T., Thompson, V., & Jarvis, R. (n.d.). Ex-Theranos employees describe culture of secrecy at Elizabeth Holmes' startup: ‘The Dropout’ podcast ep. 1. ABC News. Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://abcnews.go.com/Business/theranos-employees-describe-culture-secrecy-elizabeth-holmes-startup/story?id=60544673

- ↑ Dunn, T., Thompson, V., & Jarvis, R. (n.d.). Ex-Theranos employees describe culture of secrecy at Elizabeth Holmes' startup: ‘The Dropout’ podcast ep. 1. ABC News. Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://abcnews.go.com/Business/theranos-employees-describe-culture-secrecy-elizabeth-holmes-startup/story?id=60544673

- ↑ Eldred, S. M. (2019, October 17). What the theranos whistleblowers learned about ethics in health startups. MedCity News. Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://medcitynews.com/2019/10/what-the-theranos-whistleblowers-learned-about-ethics-in-health-startups/

- ↑ Eldred, S. M. (2019, October 17). What the theranos whistleblowers learned about ethics in health startups. MedCity News. Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://medcitynews.com/2019/10/what-the-theranos-whistleblowers-learned-about-ethics-in-health-startups/

- ↑ Eldred, S. M. (2019, October 17). What the theranos whistleblowers learned about ethics in health startups. MedCity News. Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://medcitynews.com/2019/10/what-the-theranos-whistleblowers-learned-about-ethics-in-health-startups/

- ↑ Eldred, S. M. (2019, October 17). What the Theranos whistleblowers learned about ethics in health startups. MedCity News. Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://medcitynews.com/2019/10/what-the-theranos-whistleblowers-learned-about-ethics-in-health-startups/

- ↑ 17, D., | by Sachin Waikar, & Waikar, S. (2018, December 17). What can we learn from the downfall of Theranos? Stanford Graduate School of Business. Retrieved February 11, 2022, from https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/insights/what-can-we-learn-downfall-theranos

- ↑ 17, D., | by Sachin Waikar, & Waikar, S. (2018, December 17). What can we learn from the downfall of Theranos? Stanford Graduate School of Business. Retrieved February 11, 2022, from https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/insights/what-can-we-learn-downfall-theranos

- ↑ 17, D., | by Sachin Waikar, & Waikar, S. (2018, December 17). What can we learn from the downfall of Theranos? Stanford Graduate School of Business. Retrieved February 11, 2022, from https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/insights/what-can-we-learn-downfall-theranos

- ↑ 17, D., | by Sachin Waikar, & Waikar, S. (2018, December 17). What can we learn from the downfall of Theranos? Stanford Graduate School of Business. Retrieved February 11, 2022, from https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/insights/what-can-we-learn-downfall-theranos

- ↑ 17, D., | by Sachin Waikar, & Waikar, S. (2018, December 17). What can we learn from the downfall of Theranos? Stanford Graduate School of Business. Retrieved February 11, 2022, from https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/insights/what-can-we-learn-downfall-theranos

- ↑ Kincaid, E. (2019, January 30). After Theranos, healthcare startups still aren't publishing enough peer-reviewed research, says one Stanford professor. venture capitalists disagree. Forbes. Retrieved February 11, 2022, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/elliekincaid/2019/01/30/after-theranos-healthcare-startups-still-arent-publishing-enough-peer-reviewed-research-says-one-stanford-professor-venture-capitalists-disagree/?sh=2d3824495c19

- ↑ 17, D., | by Sachin Waikar, & Waikar, S. (2018, December 17). What can we learn from the downfall of Theranos? Stanford Graduate School of Business. Retrieved February 11, 2022, from https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/insights/what-can-we-learn-downfall-theranos

- ↑ 17, D., | by Sachin Waikar, & Waikar, S. (2018, December 17). What can we learn from the downfall of Theranos? Stanford Graduate School of Business. Retrieved February 11, 2022, from https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/insights/what-can-we-learn-downfall-theranos

- ↑ 17, D., | by Sachin Waikar, & Waikar, S. (2018, December 17). What can we learn from the downfall of Theranos? Stanford Graduate School of Business. Retrieved February 11, 2022, from https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/insights/what-can-we-learn-downfall-theranos

- ↑ 17, D., | by Sachin Waikar, & Waikar, S. (2018, December 17). What can we learn from the downfall of Theranos? Stanford Graduate School of Business. Retrieved February 11, 2022, from https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/insights/what-can-we-learn-downfall-theranos

- ↑ English, V. O. A. L. (2022, January 7). Will theranos case change Silicon Valley's culture? VOA. Retrieved February 11, 2022, from https://learningenglish.voanews.com/a/will-theranos-case-change-silicon-valley-s-culture-/6382789.html

- ↑ Carson, B. (2021, December 21). The Elizabeth Holmes verdict won't change Silicon Valley. Protocol. Retrieved February 11, 2022, from https://www.protocol.com/theranos-elizabeth-holmes-verdict-impact

- ↑ Carson, B. (2021, December 21). The Elizabeth Holmes verdict won't change Silicon Valley. Protocol. Retrieved February 11, 2022, from https://www.protocol.com/theranos-elizabeth-holmes-verdict-impact

- ↑ Carson, B. (2021, December 21). The Elizabeth Holmes verdict won't change Silicon Valley. Protocol. Retrieved February 11, 2022, from https://www.protocol.com/theranos-elizabeth-holmes-verdict-impact