Sexting

Sexting has become extremely prevalent in the era of smartphones and social media apps like Kik and Snapchat. While people of all ages participate in sexting[3], it is more notably associated with adolescents and young adults. The rise in popularity of sexting is still relatively recent, therefore both ethics and legislation surrounding the topic are constantly being renewed and developed. Sexting is often seen as acceptable in certain relationships, but there are many circumstances where it is still seen as taboo behavior.

Contents

Background

The first published record of the use of the word "sexting" can be traced back to an article in The Globe and Mail in 2004, referencing explicit messages between David Beckham and an assistant. This newspaper is one of the first records to have combined the words "sex" and "text messaging". The first official record of defining the word "sexting" was in 2009 by Pew Research Center who performed a study on sexting and broke down the practice of sexting into three different types.[4] The first practice of sexting is defined as being between two romantic partners as a part of, or instead of, sexual activity. The second practice is defines sexting as being part of an experimental act for teenagers who are not sexually active. Lastly, the final practice as defined by Pew is sexting as simply a part of a prospective sexual relationship. [5]

Social Media

Kik

Kik is one of the first social media applications that brought about the idea of sexting as a prominent issue. Kik was developed in 2009 by students at the University of Waterloo in Canada. Kik has over 300 million registered users with a large portion being college-aged young adults. Kik allows people to register with a username that preserves their identity, which makes the social media platform more prone to sexting and predators. Once people discovered that a user's identity was able to be hidden on Kik, unsolicited sexting increased significantly. Many users have reported that they have received sexually explicit messages through the application and many scholars have noted Kik as an unsafe application.[6] In May 2016, Kik announced it had over 300 million users registered—8 million of which were active monthly in the United States.[7] These users were reportedly highly engaged, almost averaging about 186 monthly usage sessions.

Snapchat

Snapchat was first created in 2011 by Stanford alumnus Bobby Murphy and Stanford dropout Evan Spiegel for a product design class. The application was age-rated for users twelve and up as a multimedia messaging application in which you can share moments with friends instantly. Users are able to set how long a recipient can view a message prior to sending the "snap". In theory, the receiving user may only see the message for that certain amount of time before it is deleted automatically.[8]. Snapchat is one of the most popular messaging platforms with over 48 million monthly active users in October 2018, and its user base numbers are only second to Facebook Messenger.[9]

Since its launch, Snapchat has been commonly viewed as an application for sexting[10].It was even named, “the greatest tool for sexting since the front-facing camera”[11].

The application provides users with a sense of safety in regards to sending explicit photos since they appear to disappear from the user's device. However, the app only notifies the sender if the recipient screenshots a snap and does not disable the screenshot functionality on the phone. In addition, certain plug-in apps, such as Casper, allow users to open snaps and take screenshots without the sender being notified[12]. However, many of these applications, including Casper, have since been banned by Snapchat for running without the consent of the company.

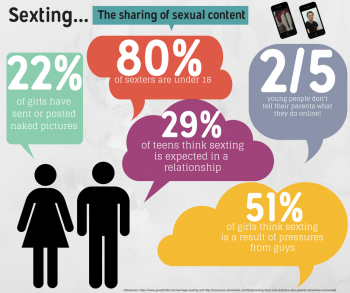

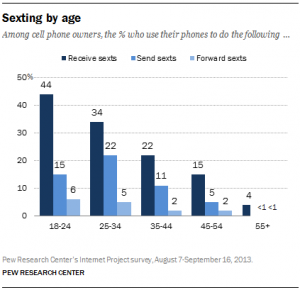

Demographics

Ethical Concerns

Texting and social media serve as platforms for users to express themselves and digitize aspects of their character and body. Sexting has given the human body the capacity to be more intimately intersected with technology, which gives rise to ethical concerns regarding data security and data privacy[14]. After sending a sext, the user no longer has control over that content — the information could be stored in the computing cloud or on another user's device via screenshot. Its ethical implications are not limited to just a loss of control over data but have also prompted privacy concerns regarding sexual harassment and bullying.

Privacy and Voyeurism

There are ways that receivers of snaps can save them forever [15]. They can screenshot the snap, which notifies the sender, or they can use someone else’s phone to take a photo of the snap which avoids the screenshot notification. In the latter, the sender would assume that their photo would never be able to be seen again, due to the lack of screenshot notification. Apps for purchase have also been created that will save snaps without notifying the sender of it. This is an invasion of both physical privacy and decisional privacy, for the original sender of the photos no longer has the freedom to decide who views the photos of their exposed body [16]. The sender has no control over whether or not these photos are shared with other audiences, or on various social media accounts like Twitter's ‘Sexy Snapchat Sluts.’ These public Twitter accounts share the nude photos of strangers for anyone to see, allowing anyone to become voyeurs. As Tony Doyle stated in Privacy and Perfect Voyeurism, “Persons are worthy of having their autonomy respected because they are persons,” [17] and accounts like these blatantly take away people’s autonomy. These accounts also violate people's privacy, which one can argue is sacrificed when someone decides to send a nude, but like autonomy, people are entitled to their own degree of privacy. Gavison writes that "privacy is [...] a shield that can protect [one] from embarrassment and enable [he or she] to maintain [their] self-respect," but due to applications like Snapchat and the growing prevalence of sexting, this shield has drastically diminished.

A notable example of third party individuals leveraging sexual photos was the blackmail and extortion attempt made by American Media Inc. AMI, against Jeff Bezos, the founder and CEO of Amazon. Bezos, who's messages with Lauren Sanchez had been compromised, revealed he had participated in sexting with a woman other than his wife. In a Medium article, Bezo's outlines the demands American Media Inc. makes in exchange for his personal photos remaining private. AMI's list of demands ranged from Bezos publicly stating that he and Gavin de Becker "have no knowledge or basis for suggesting that AMI’s coverage was politically motivated or influenced by political forces." [18] However, if agreed upon, AMI would not delete the photos, but store them if Bezos ever deviated from the agreed plan. This example brings up ethical concerns revolving around third-party individuals who are able to possess sexual photos used in a consensual exchanged between two individuals, and how the products of sexting can be leveraged against the senders.

Lauren Miranda, a 25-year-old mathematics teacher, was told in January 2019 that a male student had obtained a topless selfie of her. The principal of New York’s Bellport Middle School confronted Miranda with that information, and not long after, she was put on paid administrative leave. Miranda’s lawyer claims that school administrators told her that she could not keep her job at the school because the topless selfie made her a poor role model for students. Roughly three months later, the school board fired Miranda in a closed-door meeting. Subsequently, Miranda took action to sue the South Country School District, the superintended and Board of Education members for $3 million, on the grounds of gender discrimination. [19]

Sexual Harassment and Bullying

Sexual harassment is bullying or coercion of a sexual nature, and sexting is often a result of one person in the exchange asking or telling someone to send photos of themselves. It is often characterized as sexual harassment because the request is unwarranted and someone might be coerced into sending photos.

Public humiliation and sexual shame often result from the spreading of someone’s photos after they partook in sexting. In September of 2010, a video called Megan’s Story was put on YouTube to teach a message about sexting and demonstrate that, once you share something digitally, you lose control over who sees it and what they do with it [20]. Megan, a teenage girl, walks into school after sexting. When she enters her class, the sext she just sent begins to circulate around the classroom. Megan begins to get upset as her classmates react with a mixture of intrigue and disgust. Finally, even the teacher receives the message and Megan leaves the room in tears. [21] Having something that you sent privately for a particular person to see, shared publicly and spread around is an invasion of one’s privacy and sexual freedom. Not only that but “depression, suicide, mood disorder, adjustment reactions, and anxiety disorders are some potential mental health implications that can arise after falling victim to sexting” [22].

Sexual Pressure and Coercion

Another problem pertaining to sexting is that it is prevalent among adolescents and youths with little to no prior sexual experience. While young people are passing through puberty, they are in a stage where sexual exploration and expression may take on increased importance in their lives [23]. With the new technologies in place, adolescents are in a stronger position to be taken advantage of and coerced into sending nude photos of themselves.

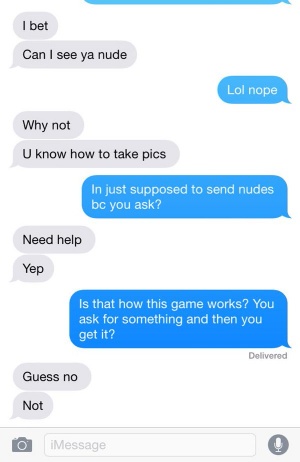

Pressure and/or coercion is a key reason why young females (in particular) send images of themselves to others (typically young males). There are a variety of ways that this pressure and coercion can formulate.

Individual Pressure

Individual pressure is best defined as the form of pressure that exists within the relationship of two sexting partners [24]. Individual pressure is also the type of pressure that typically becomes coercive. This type of pressure could entail one partner in a relationship asking for a nude image and the other partner feels obligated to send because they are in a relationship. The severity of this situation is mild but it is still coercion because the sender did not have the desire to send the photos. In a more serious example, individual pressure could involve an individual being blackmailed into sending nude images of themselves because of some threat of maybe violence, shaming, or humiliation. This example of coercion also categorizes as cyberbullying.

Peer Group Pressure

Sexting behaviors may be positively reinforced within group culture. While this type of pressure is not necessarily sexual coercion, it still puts pressure on young individuals to sext, even if they do not have the desire to do so. Group dynamics can influence individuals to sext because if everyone in the group is participating in the sexting culture, then one individual member may feel less included in the group unless they too participate in the act of sexting. In a study conducted by The National Panel to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy, revealed that 39% of teens had engaged in some form of sexting. One of the main reasons that was reported for participation in sexting was found to be peer pressure from this study. [25]

Consent

Sexting raises a plethora of new issues surrounding consent. Pressure and coercion at any level provide the legitimacy to question whether young women in some instances are able to fully and freely ‘consent’ to the activity even where they produce and send the image ‘consensually’. Additionally, consent is not always given and photos are sent to people who do not want to receive them. As mentioned previously, this is a blatant form of sexual harassment.

One of the commonly used terms in regards to non-consensual sexting is the "dick-pic." It has become a trend for males to send dick pics to others with no previous indication of the receiver asking or wanting to receive a photo. In fact, four in ten women between the ages of 18 and 36 report having been sent a dick pic without consent, while only 5% of men in this demographic reported having received unsolicited nude photos [26]. There have even been reports of women receiving dick pics via Airdrop, making anyone with the feature turned on susceptible. Lawmakers are calling the senders cyber flashers. In the UK, cyber-flashing can yield up to two years in prison.

However, US law views people under the age of 18 as being unable to give consent to sexting, even when many of them are over the legal age for sexual consent in their state. As of August 1, 2018, the age of consent in 38 out of the 50 states is under 18 [27]. This is particularly problematic because sexting is most prevalent among adolescents who already view themselves as having full sexual agency. Because of the laws set in place, a teenager who sexts consensually could be committing four different crimes: “solicitation, production, distribution and possession of child pornography” [28]. This has caused states to begin regulating the act of sexting amongst teenagers.

Legislation

Many states have taken action to create laws that they feel will properly solve this ethical dilemma. Vermont, for instance, created an exception for consensual sexting between teenagers of specific ages. Vermont Senate Bill 125 amended child pornography laws to exclude persons “less than 19 years old, [when] the child is at least 13 years old, and the child knowingly and voluntarily and without threat of coercion used an electronic communication device to transmit an image of himself or herself to the person” [29]. Other states, however, have created stricter sex offender laws in response to sexting. In 2012, South Dakota criminalized a minor’s intentional creation, transmission, possession, or distribution of “any visual depiction of a minor in any condition of nudity or involved in any prohibited sexual act” [30]. Another varying legal approach is educational programs. New York Assembly Bill 8131 “directs the attorney general to establish a 2-year juvenile sexting and cyberbullying education demonstration program in not less than 3 counties as a diversionary program for persons under 16 who have engaged in cyberbullying or sexting, in lieu of juvenile delinquency or criminal proceedings” [31]. A large ethical dilemma surrounding sexting is that many states fail to have existing laws regarding it. In these such states, prosecutors are left to follow the laws that are already established, mainly child pornography or obscenity laws. This often results in teens being labeled as sex offenders which is something that could permanently alter their lives in a negative way.

See Also

References

- ↑ Poltash, Nicole A. "Snapchat and Sexting: A Snapshot of Baring Your Bare Essentials," Richmond Journal of Law & Technology vol. 19, no. 4 (2013): p. 1-24. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/jolt19&i=654.

- ↑ US Legal, Inc. “Sexting Law and Legal Definition.” Sexting Law and Legal Definition | USLegal, Inc., definitions.uslegal.com/s/sexting/.

- ↑ McDaniel, Brandon T.; Drouin, Michelle (November 2015). "Sexting among married couples: who is doing it, and are they more satisfied?". Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 18 (11): 628–634. doi:10.1089/cyber.2015.0334. PMC 4642829. PMID 26484980.

- ↑ Rosenberg, Eli. “In Weiner's Wake, a Brief History of the Word 'Sexting'.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 30 Oct. 2013, www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2011/06/brief-history-sexting/351598/.

- ↑ Lenhart, Amanda. “Teens and Sexting: Major Findings.” Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech, Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech, 15 Jan. 2014, www.pewinternet.org/2009/12/15/teens-and-sexting-major-findings/.

- ↑ Moloney, Aisling. "What is Kik Messenger and Is It Safe?," Metro News (2017), https://metro.co.uk/2017/08/22/what-is-kik-messenger-and-is-it-safe-6870370/

- ↑ “Kik Messenger: Number of Registered Users 2016 | Statistic.” Statista, www.statista.com/statistics/327312/number-of-registered-kik-messenger-users/.

- ↑ Poltash, Nicole A. "Snapchat and Sexting: A Snapshot of Baring Your Bare Essentials," Richmond Journal of Law & Technology vol. 19, no. 4 (2013): p. 1-24. HeinOnline, https://libproxy.law.umich.edu:2195/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/jolt19&i=645

- ↑ “U.S. Mobile Messengers MAU 2018 | Statistic.” Statista, www.statista.com/statistics/350461/mobile-messenger-app-usage-usa/.

- ↑ Hill, Kashmir ’This Sext Message Will Self Destruct in Five Seconds’, FORBES, https://www.forbes.com/sites/kashmirhill/2012/05/07/fantastic-theres-a-quick-erase-app-for-sending-your-nude-photos/#7296e8e937f2

- ↑ Poltash, Nicole A. "Snapchat and Sexting: A Snapshot of Baring Your Bare Essentials," Richmond Journal of Law & Technology vol. 19, no. 4 (2013): p. 1-24. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/jolt19&i=654.

- ↑ SL, Uptodown Technologies. “Casper (Android).” Uptodown.com, 16 Aug. 2017, casper.en.uptodown.com/android.

- ↑ The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy. 10 December 2008.

- ↑ Lupton, Deborah, Digital Bodies (May 15, 2015). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2606467 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2606467

- ↑ Notopoulos, Katie. “How Anybody Can Secretly Save Your Snapchat Videos Forever.” BuzzFeed News, BuzzFeed News, 28 Dec. 2012, www.buzzfeednews.com/article/katienotopoulos/how-anybody-can-secretly-save-your-snapchat-videos.

- ↑ Floridi, Luciano. The 4th Revolution: How the Infosphere Is Reshaping Human Reality. Oxford University Press, 2016

- ↑ Doyle, Tony. “Privacy and Perfect Voyeurism.” Ethics and Information Technology, vol. 11, no. 3, 2009, pp. 181–189., doi:10.1007/s10676-009-9195-9

- ↑ Bezos, Jeff, and Jeff Bezos. “No Thank You, Mr. Pecker.” Medium, Medium, 7 Feb. 2019, medium.com/@jeffreypbezos/no-thank-you-mr-pecker-146e3922310f.

- ↑ Wong, H. (2019, April 02). A teacher claims she was fired after a student found her topless selfie. She plans to sue the district. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/2019/04/02/teacher-claims-she-was-fired-after-student-found-her-topless-selfie-she-plans-sue-district/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.48386b79ec8a

- ↑ ThinkUKnowAustralia. 2010a. Megan's Story. http://www.youtube.com/user/ThinkUKnowAUS#p/u/0/DwKgg35YbC4

- ↑ Kath Albury & Kate Crawford (2012) Sexting, consent and young people's ethics: Beyond Megan's Story, Continuum, 26:3, 463-473, DOI: 10.1080/10304312.2012.665840

- ↑ Sexting and Cyberbullying in the Developmental Context. Judge, Abigail Sossong, Anthony D. Child, and Adolescent Psychiatry and the Media 2018

- ↑ Murray Lee, Thomas Crofts, Gender, Pressure, Coercion and Pleasure: Untangling Motivations for Sexting Between Young People, The British Journal of Criminology, Volume 55, Issue 3, May 2015, Pages 454–473, https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azu075

- ↑ Murray Lee, Thomas Crofts, Gender, Pressure, Coercion and Pleasure: Untangling Motivations for Sexting Between Young People, The British Journal of Criminology, Volume 55, Issue 3, May 2015, Pages 454–473, https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azu075

- ↑ "Sexting." Mental Health and Mental Disorders: An Encyclopedia of Conditions, Treatments, and Well-Being, edited by Len Sperry, vol. 3, Greenwood, 2016, pp. 1016-1017. Gale Virtual Reference Library [[1]]

- ↑ “What makes men send dick pics?.” Moya Sarner, The Guardian, 18 Mar. 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/society/2019/jan/08/what-makes-men-send-dick-pics

- ↑ “Ages of Consent in the United States.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 14 Mar. 2019, en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ages_of_consent_in_the_United_States

- ↑ Poltash, Nicole A. "Snapchat and Sexting: A Snapshot of Baring Your Bare Essentials," Richmond Journal of Law & Technology vol. 19, no. 4 (2013): p. 1-24. HeinOnline, https://libproxy.law.umich.edu:2195/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/jolt19&i=645

- ↑ S. 125, 2009 Leg., Reg. Less. (Vt. 2009), available at http://www.leg.state.vt.us/docs/2010/Acts/ACT058.pdf

- ↑ S. 183, 2012 Leg., 87th Sess. (S.D. 2012), available at http://legis.state.sd.us/sessions/2012/Bill.aspx?File=SB183P.htm

- ↑ Assembly. B. No. A08131, 2011 Leg., Reg. Less. (N.Y. 2012) available at http://assembly.state.ny.us/leg/?default_fld=&bn=A08131&term=2011&Summary=Y&Text=Y