Senior Citizens

A senior citizen is a commonly used phrase in English to define older people within society. Specifically, it is often used to refer to a person who has retired or is around the age of 60[1]. These citizens face many problems in society, including ageism, the digital divide, somatic surveillance, and many cyber and financial crimes. These problems can lead to new forms of discrimination and more education is needed to make sure older people can thrive in the digital age. Senior citizens have been varyingly affected by the growing adoption of the internet and various new technologies.

Contents

The Digital Divide

As the world becomes more reliant on digital technology, the danger of the digital divide intensifies. The digital divide is defined as exclusion resulting from the gap between those with adequate access to digital and information technology and those without access. From calling and texting to sending emails and joining video calls, staying connected through digital technology is an essential part of modern society. What happens when this cutting-edge technology serves its primary users but marginalizes the most vulnerable?

Ageism

Ageism is the stereotyping or discrimination against individuals because of their age. According to a study, the determinants of ageism against senior citizens are influenced by personal, institutional, and cultural levels. [2] The study also concluded policymakers should prioritize anti-ageism efforts to undermine the assumption of negativity associated with age and the elderly. There is empirical evidence supporting the indirect exclusion of older people attributed to digital literacy in a digital space[2].

Digital Literacy

According to the American Library Association, digital literacy can be defined as: “the ability to use information and communication technologies to find, evaluate, create, and communicate information, requiring both cognitive and technical skills”[3].According to the American Library Association, digital literacy can be defined as: “the ability to use information and communication technologies to find, evaluate, create, and communicate information, requiring both cognitive and technical skills.” In a study aiming to measure digital literacy among older adults, researchers identified a need for instruments that aided older populations in understanding “digital content creation” and “safety”[4].

Senior Citizens v.s. Digital Literacy and Cyber Scams

The latest social media and communication platforms are not typically made for older adults. Small text sizes, low contrasting colors, and advanced digital design make products inaccessible to those who are not digital natives. As the language of technology grows and the average user becomes more advanced, interfaces get more confusing to those who are less familiar. Policies to overcome the digital divide and, more generally speaking, e-inclusion policies addressing the aging population raise some ethical problems. Among younger senior citizens, say those between 65 and 80 years old, the main issues are likely universal access to ICT and e-participation. [5]

The coronavirus pandemic has made life significantly more difficult for aging adults. Since this population is among the most vulnerable, any physical human assistance is limited. Online grocery delivery set-up, remote doctor visits, and even virtual socialization have become essential to maintaining older adults' safety and wellness. Those who cannot overcome this digital divide get left behind. With health concerns added to the mix, digital activity becomes a vital lifestyle requirement. [6] The general senior population is still marginalized from most online societies. During the pandemic, seniors are double burdened by exclusion on the digital and physical safety front. [7]

Cybercrimes and Phishing Scams

Cybercrimes towards older adults have quintupled over the last five years, racking up over 650 million dollars in financial losses each year, based on an FBI statistic. Many of these crimes also go unreported since older adults often don't know how to respond to these attacks. While there are law enforcement solutions to protect cybercrime victims, older adults are uneducated about recieving this assistance. [8]

Phishing is a significant threat to the older population of digital users. Phishing is a fraudulent attempt to elicit private information or data through impersonating another person's identity. This is most common through emails, auction sites, and social networking platforms. Foreign emails about a Nigerian prince or a long-lost cousin target older users and attempt to take their money. Since older adults are less familiar with the digital world, they are significantly more vulnerable to phishing scams.

What To Do

While the world can't simply teach every older adult how to be a tech-savvy internet surfer, organizations could develop better informative materials for older adult's education and safety in the digital world. Users can also be more aware of cybercrimes that target older populations. There are many technology education resources for older adult users and best practices for smaller tasks such as password management. For example, it is much safer for older adults to keep several passwords written down on a piece of paper at their desk than to have the same password for all their accounts. These practices, while seemingly nontrivial, could make up the difference between safe digital activity and vulnerable digital activity. Some resources to help older adults understand how to use technology can be found here:

| FBI Scam Reporting | The FBI provided information outlining various examples of elder fraud, common fraud schemes, and ways to protect yourself or loved ones. Additionally, this resource links to the FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center and allows for direct reporting of suspected fraud. [9] |

|---|---|

| Fraud.org | Fraud.org is a consumer advocacy organization that allows users to sign up for alerts on common scams and fraud schemes. There is also a section dedicated to filing complaints about fraudulent experiences. [10] |

| AARP | The AARP is a nonprofit organization dedicated to improving the lives of Americans over the age of 50. This resource provides access to technology training classes and insight into the value of tech training for older adults. [11] |

| Seniorliving.org | Seniorliving.org uses its board of senior care and safety experts to curate over 2,500 guides and articles, review alert systems for over 75,000 readers. This link, in particular, provides information on quality internet service providers for seniors, virtual retirement communities, senior tech products, and fraud prevention techniques. [12] |

Inaccessible Platforms

Every update and rebrand that a tech company publishes attempts to make their user experience more efficient and convenient for the primary user. Unnecessary words are removed. A “search” button is replaced with a magnifying glass icon. With these ‘sleek’ updates, older adults become more confused and lost. Don Norman explains, “Current interaction designs often feature illegible text, tiny targets, startling sounds, and other features that make the online world unfriendly to older users.” [13] Based on his research, he states things like small, lightly colored text on mobile interfaces and interactive elements such as dropdown items are challenging to this demographic. Other common conventions such as links, copy/pasting, and pop-up windows can elicit frustration to older internet users. Forms that time out after too long also make it difficult for older adults to use. The demographic spends much more time analyzing each page in a digital interface before understanding what they are viewing. Many older adults suffer from memory loss. Remembering passwords, usernames, and other sensitive information is also extremely difficult. And since they are unfamiliar with the internet, time is also a major factor in their activity. Older adults consume visual media differently than new digital natives do. Design patterns and visual cues are just not universal across these two groups.

Somatic Surveillance

Modern information technology has also increased the possibilities for supervision and surveillance of senior citizens. Examples already meriting researchers' attention include behavioral pattern monitoring systems, in which behavior patterns of elderly subjects are monitored and any changes detected are reported to caregivers. [14] Research to analyze changes in behavioral patterns over time to provide early warning of age-related diseases (such as Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s) is already being undertaken. Experts foresee that, within a decade, software efficient enough to spot early Parkinson’s symptoms will be commercially available. Relevant supervision technologies in welfare services include sensors in exit doors warning about undesired movement and electronic tags for localization of the elderly. Sensitive data produced by ICT services may represent an invaluable source of information for many companies' marketing departments, and they could be covertly generated, stored, and commercialized.

Moreover, ancillary information generated by the system can discriminate against ethnic groups and other minority groups. [15] Certain technologies are particularly suited for generating shadow data (e.g., age, gender, skin color, style in clothes, etc.) which could be used for illicit ethnic or religious classification. Somatic surveillance is a concern in the medical domain. Increasingly, consumerist strategies promise ‘‘eternal youth’’ by manipulating the body through bio, info, and nanotechnologies. [16] As a result, senior citizens' bodies are invaded by microtechnologies, reconstructed as nodes in vast information networks, and controlled through automated responses or network commands. [17] This trend requires ethical reflections on the concept of respect for bodily and mental integrity in advanced ages. An important ethical tenet is that sensitive data should not be required in return for essential services unless the information is necessary to execute those services properly.

Senior citizens and cashless systems

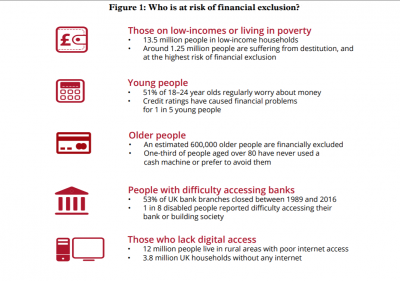

Ageism and financial exclusion can often come together to prevent senior citizens from using cashless systems. As cashless systems become more popular, Senior citizens might not be able to use or access such cashless systems in their entirety. Banking institutions may allow access to such systems in every way, but they often do not do enough to educate older citizens about using these systems effectively and safely.

While cashless systems had faced many hurdles in the past, with the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic, many businesses have started to adopt cashless systems, and legislation has become more lenient [19]. This was only furthered by the national coin shortage in the United States [20]. Due to the widespread adoption of such digital systems and the impacts of the digital divide on the elderly, senior citizens' finantial exclusion has increased [21]. Senior citizens are generally confused by cashless systems, and this mostly centered around the numerous potential avenues for completing such a purchase [22]. Because many mobile wallets are created for younger customers, digital literacy and design choices can significantly impact how senior citizens can interact and understand such cashless payment systems. Moreover, senior citizens often do not have a credit card: a primary form for which cashless payments are executed [23].

Additionally, many senior citizens do not use the internet. Because of this, online payment systems are often inaccessible [24]. A lack of internet access can be for many reasons, some of which include location, poverty, and education. Singapore has started to educate senior citizens on navigating a digital age through special programs called Silver Infocomm Junctions. These programs teach seniors how to make electronic payments safely and significantly facilitate the change to a cashless society. Moreover, cybercrimes can play a role here, and infrastructure to support cashless systems must take cyber crimes against the elderly into account [25].

Evolution Over Time

While many older adults are still unable to send a text message on their own, this population of digitally literate users is shrinking. In the last 18 years, older adults have become slightly more technologically proficient due to the digital world's age. There is a promise that foundational blockers that challenge older adults, such as basic emailing concepts, will phase out as the older population becomes more familiar with the internet's dawn. But since technology expands and matures at an exponential rate, it is clear there will always be new updates to digital proficiency that favor younger users and change too quickly for older users to keep up. [26]

How can technologies support older adults and allow them to stay connected to a world that's rapidly expanding online? Designers of technology make platforms accessible to older adults who need them. It is a requirement for interfaces essential for digital navigation- such as emails, Facebook, grocery ordering, hospital appointment booking- to be accessible to those who suffer from poor vision, hearing, or memory retention. Seniors are a vulnerable population in the digital world. They need proper education and protection for digital devices that have become so crucial to the modern world. [27]

References

- ↑ Older persons. (n.d.). Retrieved April 07, 2021, from https://emergency.unhcr.org/entry/43935/older-persons

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Marques, S., Mariano, J., Mendonça, J., De Tavernier, W., Hess, M., Naegele, L., . . . Martins, D. (2019). Determinants of ageism against older adults: A systematic review. National Institute of Health. doi:10.31234/osf.io/g37ej

- ↑ "Digital Literacy", American Library Association, August 2, 2016. http://www.ala.org/pla/initiatives/digitalliteracy (Accessed April 6, 2021) Document ID: 9f9c68ca-b4b6-22e4-1945-6c7ff10523af

- ↑ Oh, S. S., Kim, K., Kim, M., Oh, J., Chu, S. H., & Choi, J. (2021). Correction: Measurement of digital literacy among older adults: Systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(3). doi:10.2196/28211

- ↑ World Leaders in Research-Based User Experience. (n.d.). Usability for seniors: Challenges and changes. Retrieved March 15, 2021, from https://www.nngroup.com/articles/usability-for-senior-citizens/

- ↑ Chen, A., Ge, S., Cho, S., Teng, A., Chu, F., Demiris, G., & Zaslavsky, O. (2020, August 10). Reactions to Covid-19, information and technology use, and social connectedness among older adults with Pre-frailty and frailty. Retrieved April 02, 2021, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0197457220302457

- ↑ Seifert, A., Cotten, S., & Xie, B. (2020, July 16). Double burden Of Exclusion? Digital and social exclusion of older adults in times of covid-19. Retrieved April 02, 2021, from https://academic.oup.com/psychsocgerontology/article/76/3/e99/5872331?login=true

- ↑ Fazzini, Kate. “Here's How Online Scammers Prey on Older Americans, and What They Should Know to Fight Back.” CNBC, CNBC, 23 Nov. 2019, www.cnbc.com/2019/11/23/new-research-pinpoints-how-elderly-people-are-targeted-in-online-scams.html.

- ↑ FBI. (2020, June 15). Elder fraud. Retrieved April 07, 2021, from https://www.fbi.gov/scams-and-safety/common-scams-and-crimes/elder-fraud

- ↑ Staff, F. (2021, April 01). Fraud.org staff. Retrieved April 07, 2021, from https://fraud.org/common-scams/

- ↑ Frank, D. (2018, July 24). Tech training helps older americans socialize. Retrieved April 07, 2021, from https://www.aarp.org/home-family/personal-technology/info-2018/technology-training-for-older-adults.html

- ↑ Hoyt, J. (n.d.). Technology for seniors and the elderly (1294626970 953549684 J. Hoyt, Ed.). Retrieved April 07, 2021, from https://www.seniorliving.org/tech/

- ↑ World Leaders in Research-Based User Experience. (n.d.). Usability for seniors: Challenges and changes. Retrieved March 15, 2021, from https://www.nngroup.com/articles/usability-for-senior-citizens/

- ↑ Foucault, M. (2001). The birth of social medicine. In J. D. Faubion (Ed.), Essential works of Michel Foucault 1954–1984. London: Penguin. Accessed: 28 March 2021.

- ↑ Monahan, T., & Wall,T. (2007). Somatic surveillance. Surveillance and Society, 4(3), 154–173. Accessed: 28 March 2021

- ↑ Sakairi, K. (2004). Research of robot-assisted activity for the elderly with senile dementia in a group home. SICE 2004 Annual Conference, Vol. 3, Aug 2004, pp. 2092–2094. Accessed: 28 March 2021.

- ↑ Grundy, E. (2006). Aging and vulnerable elderly people: European perspectives. Aging & Society., 26, 105–134 Accessed: 28 March 2021

- ↑ Who is at risk of financial exclusion?1 [Digital image]. (2017, March 25). Retrieved April 08, 2021, from https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld201617/ldselect/ldfinexcl/132/132.pdf available for distribution under Parliamentary copyright.

- ↑ Allam Z. (2020). The Forceful Reevaluation of Cash-Based Transactions by COVID-19 and Its Opportunities to Transition to Cashless Systems in Digital Urban Networks. Surveying the Covid-19 Pandemic and its Implications, 107–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-824313-8.00008-5

- ↑ Board of governors of the Federal reserve system. (n.d.). Retrieved April 07, 2021, from https://www.federalreserve.gov/faqs/why-do-us-coins-seem-to-be-in-short-supply-coin-shortage.htm

- ↑ Warchlewska, A. (2020). WILL THE DEVELOPMENT OF CASHLESS PAYMENT TECHNOLOGIES INCREASE THE FINANCIAL EXCLUSION OF SENIOR CITIZENS?. Acta Scientiarum Polonorum. Oeconomia, 19(2), 87-96. https://doi.org/10.22630/ASPE.2020.19.2.21

- ↑ Ghosh, A. (2017). Turning India into a CASHLESS economy: The challenges to overcome. SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2989290

- ↑ Jung, K., & Kang, M. (2021). Understanding Credit Card Usage Behavior of Elderly Korean Consumers for Sustainable Growth: Implications for Korean Credit Card Companies. Sustainability, 13(7), 3817. doi:10.3390/su13073817

- ↑ Peoples, C., Moore, A., & Zoualfaghari, M. (2020). A review of the opportunity to CONNECT elderly citizens to the Internet of Things (IoT) and gaps in the service level Agreement (SLA) provisioning process. EAI Endorsed Transactions on Cloud Systems, 6(18), 165993. doi:10.4108/eai.22-5-2020.165993

- ↑ : Fabris, Nikola (2019) : Cashless Society – The Future of Money or a Utopia?, Journal of Central Banking Theory and Practice, ISSN 2336-9205, De Gruyter Open, Warsaw, Vol. 8, Iss. 1, pp. 53-66, http://dx.doi.org/10.2478/jcbtp-2019-0003

- ↑ Unai Diaz-Orueta, L. (n.d.). Shaping technologies for older adults with and without dementia: Reflections on ethics and Preferences - Unai diaz-orueta, Louise hopper, EVDOKIMOS konstantinidis, 2020. Retrieved March 15, 2021, from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1460458219899590

- ↑ Seifert, A., Cotten, S., & Xie, B. (2020, July 16). Double burden Of Exclusion? Digital and social exclusion of older adults in times of covid-19. Retrieved April 02, 2021, from https://academic.oup.com/psychsocgerontology/article/76/3/e99/5872331?login=true