SNAP and Other Federal Nutrition Programs

One of the largest federal nutrition programs is the United States Department of Agriculture Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), formerly known as "Food Stamps", which aims to supplement needy households’ food budgets “so that they can purchase healthy food and move towards self-sufficiency.” [2] This program reached 38 million people nationwide in 2019, of which more than 66% were in families with children; average monthly SNAP benefits for each household member ranged from $100-200 depending on location. [3] Given that the U.S. population in 2019 was 328.46 million people,[4] this means that 11.57% of the U.S. population was enrolled in the SNAP assistant program in 2019. SNAP and other federal nutrition programs worldwide have information technology-related ethical implications because many use algorithms to determine individual and family eligibility. Ethical concerns include failure to meet needs, decision power, health concerns, and healthcare costs. This article also addresses related welfare program case studies.

Overview

Eligibility

The determination of eligibility follows a set of strict federal rules. To be eligible for benefits, a household’s income and resources must meet three core criteria: gross monthly income must be at or below 130 percent of the poverty line (which as of 2021 the federal poverty line income for a family of 4 is $26,500), [5] net income must be at or below the poverty line, and assets must fall below certain limits. Additionally, there are certain groups of people who are not eligible for SNAP benefits regardless of their income, including individuals on strike, unauthorized immigrants, and some lawfully present immigrants. [6] The mass formula for determining eligibility skips people that do not qualify numerically.

A Note on COVID-19

During the pandemic, avoiding public areas such as grocery stores is important when individuals have pre-existing conditions. The United States Center for Disease Control recommends avoiding public spaces to limit the risk of exposure to COVID-19. [7] Many people have to rely on grocery delivery services, and very few online grocery delivery services will accept SNAP payments. This difficulty in using SNAP benefits during COVID-19 raises food security concerns for many individuals. [8]

History

The College Student Hunger Act of 2019

The College Student Hunger Act is a bill to amend the Food and Nutrition Act of 2008 to expand the eligibility of students to participate in the supplemental nutrition assistance program. [10] The new bill will address student hunger by increasing low-income college students' ability to access SNAP, testing new ways SNAP can be administered on college campuses, and increasing awareness about student eligibility for SNAP. Specifically, the bill: [11]

- Increases low-income college students' ability to receive SNAP: Expands the list of criteria that permits low-income college students to apply for SNAP by allowing Pell Grant-eligible students and independent students to apply for benefits. It also lowers SNAP's 20 hours per week work requirement for college students to 10 hours. [11]

- Increases outreach to eligible students: Requires the Department of Education to notify low-income students who are eligible for a Pell Grant that they may be eligible for SNAP, and to refer them to states' SNAP application websites.[11]

- Creates a SNAP student hunger pilot program: Requires the Departments of Agriculture and Education to run demonstration pilot projects to test ways to make SNAP more useful to college students. [11]

- Increases awareness of student eligibility for SNAP: Implements the U.S. Government Accountability Office's recommendations by requiring the Department of Agriculture to increase awareness among states and colleges about student hunger, student eligibility for SNAP, and how states and colleges can help eligible students access and use their SNAP benefits. [11]

The Consolidated Appropriations Act 2021

Under regular SNAP rules, students enrolled at least half-time in an institution of higher education are ineligible for SNAP unless they meet one of the exemptions. However, the Consolidated Appropriations Act temporarily expands SNAP eligibility to allow students who either: [12]

- Are eligible to participate in state or federally financed work-study during the regular academic year, as determined by the institution of higher education; or [12]

- Have an expected family contribution (EFC) of 0 in the current academic year. This includes students who are eligible for a maximum Pell Grant. [12]

Beginning January 16, 2021, students who meet one of the two criteria outlined above may receive SNAP if they meet all other financial and non-financial SNAP eligibility criteria. The new, temporary exemptions will be in effect until 30 days after the COVID-19 public health emergency is lifted. [13]

Ethical Concerns

Failure to Meet Needs

There are many cases of individuals and families in need of food that do not qualify for SNAP based on the mass formula algorithm. More than 41 million people are "food insecure", meaning that they do not have consistent access to adequate food, and roughly 1 in 4 of these individuals are not likely to be eligible for programs such as SNAP. Having these hard guidelines for eligibility means that there are some cases where individuals miss the qualification by a few dollars over the limit. [14] Additionally many individuals that are on SNAP benefits struggle to make ends meet with the small allotment decided upon. Despite the algorithm determining they have sufficient funds; NPR gives specific examples of individuals with food security struggles. [8]

Due to changes in congressional power and presidency, there are amendments made to the existing eligibility requirements. One of the more recent changes cut off an estimated 700,000 unemployed people from food assistance provided by SNAP. [15] This change targeted a group of people known as able-bodied adults without dependents. Taking support from some of those individuals can harm more than just them -- many of those people share their benefits with family or their social network and can create a ripple-effect from these cuts.

It is not clear at this time whether SNAP eligibility determination specifically is automated. This lack of transparency is an ethical issue itself - there is no available information on how this formula is used in practice in terms of automation.

Decision Power

Bias in information systems also can exist within public services, not just private corporations. There are deep historical roots of biases against the poor that characterize today’s “tools of digital poverty management”. These biases exist in information technologies and their corresponding algorithms, [16] including SNAP.

These federal nutrition programs can be thought of in the context of a “weapon of math destruction”. Cathy O’Neil, coiner of this term, says that these WMDs can combine data injustice and systemic inequality to trap poor people in negative “feedback loops”. O'Neil says math is demonstrated to be not only in the world’s problems but also fueling them, [17] and this math determine which individuals qualify for social benefits. This ethical concern of lack of inclusivity and representation aligns with O'Neil's "weapon of math destruction" because not enough people are represented by the algorithm. [14] Numbers such as income and assets make the difference between “food insecure” and food security.

When algorithms, like the mass equations used in SNAP, do not consider possible biases by the humans who wrote them, the biases can have lasting effects. A study done by Obermeyer et al. found that commercial algorithms used by the U.S healthcare system continuously concluded that black patients were healthier than white patients. The algorithm was inherently incorrect because it used health costs as a proxy for health needs, and less money is spent on black patients with the same need. [18] Context of the actual situation sometimes needs to be utilized instead of trusting an algorithm’s outcomes. With SNAP, individuals and families who are on the border are concluded as food secure when that is not the case. [8]

Health Impacts

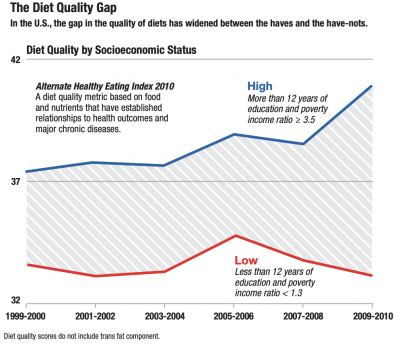

Determination from this information technology has ethical implications on the health and well-being of individuals. Failure to meet qualifications for SNAP and other federal nutrition programs means that many individuals have to make the most of their money by skipping meals, buying the cheapest (processed) foods, and not having the support to purchase more expensive fresh foods such as fruits and vegetables. [14] The current benefit maximum allotment is 115% of the June 2020 value of the Thrifty Food Plan (TFP), which is roughly $45 per week for males and $40 per week for females. [20]

A review of 27 studies in 10 countries including the United States found that "unhealthy" food is on average $1.50 cheaper per day than healthy food. Given the relative cost of processed and “healthy” foods, it is easier to meet daily nutritional needs by spending this little amount of money on "unhealthy" foods. These cheaper foods are less nutritious than the latter and can put individuals at higher risks for health problems. [21] Davis' research has shown that the Thrifty Food Plan does not consider labor cost and is thus inadequate. Using a basic labor economics technique, the study determined that with labor included, the mean household falls short of the TFP health guidelines even with the determined monetary resources. [22] Children living in low-income families have worse health outcomes on average than other children on several indicators such as obesity and mental health. [23] These negative health correlations with poverty levels are extended from these federal nutrition support programs.

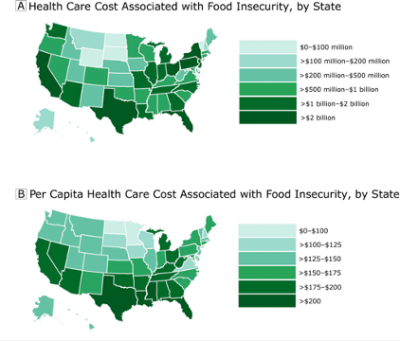

Healthcare Cost of Food Insecurity

The failure to meet SNAP's qualifications leads to an increase in healthcare expenses for the left-out individuals on the border. In a longitudinal cohort study, the researchers showed that being food insecure was associated with significantly more emergency room visits, hospitalizations, and days hospitalized. [25] The average cost of an emergency room visit in 2017 was $1,389. [26] That price can be lower with insurance, but with high deductibles, the individual would still have to pay the full price if they haven’t reached their deductible. [27] With these added costs, individuals who are food insecure had annual health care expenses that were $1834 higher than individuals who are food secure. The total median annual health care cost for food-insecure individuals was $687,041,000. [24]

These costs add an increased strain on food insecure individuals as compared to food secure individuals and perpetuate the poverty cycle. Food insecurity is linked with poorer health outcomes, as well as higher health care costs. This cycle continues because there is a link between high health care needs and greater out-of-pocket costs and higher levels of food insecurity. [28] This cycle is especially difficult to break out of for children who grew up in poverty. Out of the children who experience moderate-to-high levels of poverty, 35% to 46% are also poor throughout early and middle adulthood. [29]

Case Studies

Indiana and IBM

In 2006, former Indiana governor Mitch Daniels announced a $1.34 billion plan for a welfare reform program that would partner with IBM to use artificial intelligence to streamline the application and fraud identification processes [31] [32]. The goal was to create a more “fair” selection system and lower costs to taxpayers. Critics immediately advocated against the partnership, arguing that welfare should not be privatized. Within nine weeks of the program’s start, the call centers were experiencing major interview scheduling issues and the number of vanishing personal verification documents (drivers licenses, passports, social security cards, etc.) was rising exponentially due to lack of digital organization. The program was also not providing the expected benefits, caseworkers became data monkeys and their social work degrees were left unused during the program’s run. Furthermore, some of the caseworkers used their new expansive power over all applications to perpetrate fraud and receive unneeded benefits from the systems [31]. The increased fraud was estimated to cost Indiana taxpayers an estimated $100 million per program year. The system’s failure to keep track of applicant’s documents and records was blamed on applicants themselves. Many received notification of “failure to cooperate” and a denial of benefits [32]. Three years into the failing program in October of 2009, Indiana canceled their contract with IBM and sued for 170 million USD in damages. IBM then countersued Indiana for $52.8 million for equipment costs. The state’s supreme court upheld a ruling of $78 million owed by IBM to the state of Indiana in September of 2018. Each side continues to blame each other for contract inaccuracies and failure to provide services; however, the victims of Indiana and IBM’s negligence were the state’s most needy citizens [33]. This came at a time of increased need for welfare services due to “deteriorating state and national economies and statewide national disasters” [32].

References

- ↑ Office on Aging. (n.d.). Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Outreach

- ↑ United States Department of Agriculture. (n.d.). Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) | USDA-FNS. USDA Food and Nutrition Service. Retrieved March 18, 2021, from https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/supplemental-nutrition-assistance-program

- ↑ Hall, L. (Jan. 12, 2021). “A Closer Look at Who Benefits from SNAP: State-by-State Fact Sheets”. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

- ↑ Plecher, Published by H. “United States - Total Population 2025.” Statista, 6 Jan. 2021, www.statista.com/statistics/263762/total-population-of-the-united-states/.

- ↑ “Poverty Guidelines.” ASPE, 16 Mar. 2021, aspe.hhs.gov/poverty-guidelines.

- ↑ (Sept. 01, 2020).“A Quick Guide to SNAP Eligibility and Benefits”. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

- ↑ (October 28, 2020). Deciding To Go Out. United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Gingold, Naomi. (April 30, 2020). “Coronavirus Pandemic Complicates Getting Groceries with SNAP”. NPR.

- ↑ Gao-19-95 (Jan 09, 2019). Food Insecurity:Better Information Could Help Eligible College Students Access Federal Food Assistance Benefits. United States Government Accountability Office. Retrieved April 02, 2021

- ↑ “S. 2143 — 116th Congress: College Student Hunger Act of 2019.” www.GovTrack.us. 2019. April 2, 2021 <https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/116/s2143>

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 Elizabeth Warren (Jul 17, 2019). Press Release. Senator Warren and Representative Lawson Introduce the College Student Hunger Act of 2019 to Address Hunger on College Campuses Senate|Gov. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 USDA Press Office (Feb 13, 2021). Education Department Amplifies USDA Expansion of SNAP Benefits to Help Students Pursuing Postsecondary Education During Pandemic U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved April 2, 2021

- ↑ Federal Student Aid (Feb 23, 2021). SNAP benefits for eligible students during the COVID-19 pandemic (EA ID: GENERAL-21-11) Retrieved April 2, 2021

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Vasel, Kathryn. (May 30, 2018). “Too poor to afford food, too rich to qualify for help”. CNN Business.

- ↑ Dickinson, Maggie. (December 10, 2019). The Ripple Effects of Taking SNAP Benefits From One Person. The Atlantic.

- ↑ Eubanks, V. (2017). Chapter 1 From Poorhouse to database. In Automating Inequality. NY: St. Martin’s Press.

- ↑ O’Neil, C. (2016). Introduction. In Weapons of Math Destruction: How Big Data Increases Inequality and Threatens Democracy. New York: Crown Publishing Group.

- ↑ Obermeyer, Z., Powers, B., Vogeli, C., & Mullainathan, S. (2019, October 25). “Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations.”. ScienceMag.org.

- ↑ Policy Statement (Mar, 2017). Farm Bill Policy and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) American Heart Association|American Stroke Association.

- ↑ (July, 2020).Official USDA Food Plans: Cost of Food at Home at Four Levels, U.S. Average, June 2020 1. United States Department of Agriculture.

- ↑ Rao, Mayuree, et. al. "Do healthier foods and diet patterns cost more than less healthy options? A systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ Journals, Accessed March 11, 2021.

- ↑ Davis, G., You, W. (April 2020). The Thrifty Food Plan Is Not Thrifty When Labor Cost Is Considered, The Journal of Nutrition, Volume 140, Issue 4, April 2010, Pages 854–857

- ↑ Gupta, R. P., de Wit, M. L., & McKeown, D. (2007). The impact of poverty on the current and future health status of children. Pediatrics & child health, 12(8), 667–672. https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/12.8.667

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Berkowitz SA, Basu S, Gundersen C, Seligman HK. [State-Level and County-Level Estimates of Health Care Costs Associated with Food Insecurity. Prev Chronic Dis 2019;16:180549. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd16.180549

- ↑ Berkowitz, S., Seligman, H., Meigs, J., & Basu, S. (2018, September 10). “Food insecurity, healthcare utilization, and high cost: A longitudinal cohort study”.

- ↑ (Nov. 12, 2020).“Emergency room vs. urgent care: Differences, costs & options”. Debt.org.

- ↑ Hunt, Janet. (Mar. 03, 2021). “Average Cost of an ER Visit”<. The Balance.

- ↑ Sonik, R. A. (2019). “Health insurance and FOOD Insecurity: Sparking a Potential virtuous cycle”. American Journal of Public Health, 109(9), 1163-1165. doi:10.2105/ajph.2019.305252

- ↑ Wagmiller, R., & Adelman, R. (2009, November).“Childhood and intergenerational poverty: The long-term consequences of growing up poor”. National Center for Children in Poverty.

- ↑ Eubanks, B. (May 27, 2015). Want to Cut Welfare? There’s an App for That. The Nation. Retrieved April 02, 2021

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Eubanks, V. (2018). Automating inequality: how high-tech tools profile, police, and punish the poor. First edition. New York, NY: St. Martin's Press.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 IBM Seeks Enforcement of Indiana Welfare Contract. (2010, May 18). Manufacturing Close-Up. Retrieved from https://bi.gale.com/essentials/article/GALE%7CA227232599?u=umuser&sid=summon

- ↑ Callahan, R. (2018, September 28). Appeals court affirms ruling that IBM owes Indiana $78M. AP NEWS. https://apnews.com/article/36ba0562a02142e5adfe39518e2e0f85