Rape In Cyberspace

"A Rape in Cyberspace, or How an Evil Clown, a Haitian Trickster Spirit, Two Wizards, and a Cast of Dozens Turned a Database into a Society" is an article written by journalist Julian Dibbell, first published in The Village Voice in 1993[1]. The piece was later incorporated into Dibbell's book titled My Tiny Life which recounts his experiences and observations from his time on LambdaMOO, a text-based virtual reality.

"A Rape in Cyberspace" is considered the most comprehensive record of the first virtual rape or cyber rape on the Internet and is often cited in the literature and in research surrounding the topic [2]. In his article Dibbell details, the aftermath of the attack on the virtual community and its struggle to determine an appropriate punishment for the virtual rapes because, although not technically criminal, these attacks negatively impacted the victim's real-life psyches.

Contents

LambdaMOO

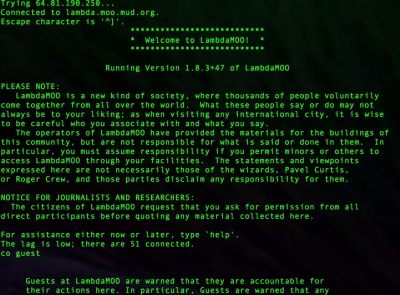

The unprovoked attacks described in “A Rape in Cyberspace” took place in the virtual reality of LambdaMOO, a text-based online community which is an extension of MUD, a multi-user dimensions computer game[3]. LambdaMOO is completely text-based so setting and avatars are rendered through descriptive text and there are no graphics or animations to accompany the text descriptions. Players interacted with each other, objects and locations by using avatars[3]. Players are given the freedom to customize the text description of their avatars in any way they would like including their preferred gender and describing their outward appearance [1].

Summary

The Attack

On a night in March of 1993, the avatar Mr. Bungle entered Living Room #17, a very popular meeting site on LambdaMOO, and forced two other players, Legba and Starsinger, to perform explicit and sexual acts [1]. Mr. Bungle was able to force these actions upon other players through the use of a voodoo doll, a subprogram that enables the user to override controls so that a statement written by one user appears to be attributed to another user[4]. As a result, an avatar does and says things that the avatar’s user did not intend or want their avatar to do. Mr. Bungle with the help of his voodoo doll subprogram was able to manipulate and control the actions of the other players even when he was in an entirely different room[1]. The attack lasted until someone summoned a wizard named Zippy, a player with administrator level access, who was able to cage Mr. Bungle. The caging caused Mr. Bungle to lose access to the LambdaMOO community without the deletion of his avatar or account, thereby end his attack on the community that night but not his presence in the online community[4].

Community Response

The actions committed by Mr. Bungle violate the community norms that had been established within LambdaMOO. Mr. Bungle’s conduct elicited outrage from the community and its members[5]. The day following the attack, Legba posted a statement on the in-MOO mailing list, social-issue, a form in which member could talk about and debate issues important to the entire community [4] In her statement Legba, although still confused about how she should feel after the attack, did call for some kind of repercussion.

"I’m not calling for policies, trials, or better jails. I’m not sure what I’m calling for. Virtual castration, if I could manage it. Mostly, [this type of thing] doesn’t happen here. Mostly, perhaps I thought it wouldn’t happen to me. Mostly, I trust people to conduct themselves with some veneer of civility. Mostly, I want his ass.”[1] - Legba

The user behind Legba later confused to Dibbell that she wrote her statement with tears streaming down her face due to the trauma she experienced from her virtual rape[1]. Later Legba called for Mr. Bungle to be toaded, or to have his account and avatar removed from LambdaMOO. However, Legba did not have the technological capacity to toad Mr. Bungle from the community and need the assistance of a wizard to remove Mr. Bungle from the database. At this point at the time, the LambdaMoo community did not have any formal organizational structure in place and primarily ran on majority rules decision-making process[6]. Despite the intentional support Legba received, the community quickly became divided on how to handle the situationCite error: Invalid <ref> tag;

refs with no name must have content. On the third day after the incident, LambdaMOO users gathered to disuse the fate of Mr. Bungle. In the middle of the meeting, Mr. Bungle joined the conversation saying that his actions were a consequence of the virtual reality and that in they had no bearing on his real life[1]. The left the discussion quickly after his explanation was met with hostility. Despite a lengthy conversation, the users did not come to a resolution.

Consequences

After the meeting, a wizard named JoeFeedback weighed the arguments and decided to take action upon himself. He quickly and silently removed Mr. Bungle from the LambdaMOO database and with this action the character of Mr. Bungle ceased to exist. Despite the character being kicked off the avatar’s users did not experience the same punishment. A few days later, the user returned to the platform in the form of a new character named Dr. Jest but he quickly left the site and has not been seen since. The actions of Mr. Bungle had an everlasting effect on LambdaMOO, by forcing a diverse group of users to come together to form a community with its own rules and regulations. As a result, LambdaMOO's main creator Pavel Curtis set up a system of petitions and ballots where users can put any topic up to a popular vote and in which community wizards are required to implement the outcome of the vote[7]. The system helped to create a government for the community and provided ways to protect against acts of violence on the site[7].

Ethical Implications

In his article, Dibble debates the difference between real life versus virtual reality. Dibbell argues that the world of LambdaMOO is not either completely real or completely make-believe but exists somewhere in-between with complex thoughts and feelings[1]. He brings to light the ethical question of does virtual reality effect real life and can virtual harm create harm in real life. The actions committee by Mr. Bungle on that night in March were virtual sexual assault, or sexually explicit behavior forced upon one virtual character by another virtual character in a virtual environment as defined by Danaher, and had real-life effects on the users who were victims [3]. Mr. Bugle through the virtual harm and sexual assault virtually harmed his victims’ avatars. Avatars can be viewed as virtual representations or extensions of real-life people and even in some cases a truer representation of themselves when society views their certain characteristics are negative or odd [8]. Since avatars are an extension of their real-life counterparts any harm done onto the avatar effects the users who created the avatar as seen in the case of Legba and Starsinger who were deeply distraught and angered Mr. Bungle's actions.

External Links

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Dibbell, Julian. "A Rape in Cyberspace." The Village Voice. 21 December 1993

- ↑ Fenech, Melissa Mary. "Questions about accountability and illegality of virtual rape" (2009). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 11046. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/11046

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Danaher, John. “The Law and Ethics of Virtual Sexual Assault.” Research Handbook on the Law of Virtual and Augmented Reality, 21 Dec. 2018, pp. 363–388.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Johnson, Laurie. “Rape and the Memex – Laurie Johnson.” Refractory, 30 May 2011, refractory.unimelb.edu.au/2008/05/22/rape-and-the-memex-laurence-johnson/.

- ↑ Kiesler, Sara & Kraut, Robert & Resnick, Paul & Kittur, Aniket. (2012). Regulating Behavior in Online Communities.

- ↑ Mnookin, Jennifer L. “Virtual(Ly) Law: the Emergence of Law in LambdaMoo: Mnookin.” OUP Academic, Oxford University Press, 1 June 1996, doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.1996.tb00185.x.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Brennan, Linda L., and Victoria Johnson. Social, Ethical and Policy Implications of Information Technology. Information Science Pub., 2004.

- ↑ Spence, Edward H., et al. “Virtual Rape, Real Dignity: Meta-Ethics for Virtual Worlds.” The Philosophy of Computer Games Philosophy of Engineering and Technology, 2012, pp. 125–142.