Predictive Policing

Overview

Predictive policing is a term used to describe the application of analytical techniques on data with the intent to prevent future crime by making statistical predictions. This data includes information about past crimes, the local environment, and other relevant information that can be used to make predictions about crime.[1] It is not a method for replacing traditional policing practices such as hotspot policing, intelligence-led policing, or problem-oriented policing. It is a way to assist conventional methods by applying the knowledge gained from algorithms and statistical techniques.[2] The utilization of predictive policing methods in law enforcement has received criticism that it challenges civil rights and civil liberties, and its algorithms could exacerbate racial biases in the criminal justice system.[3]

In Practice

Predictive policing practices can be divided into four categories: predicting crime, predicting offenders, predicting perpetrator's identities, and predicting victims of crime.[1] It can also be categorized into place-based, which makes geographic predictions on crime, or person-based in which make predictions about individuals, victims, or social groups involved in crime. [4]

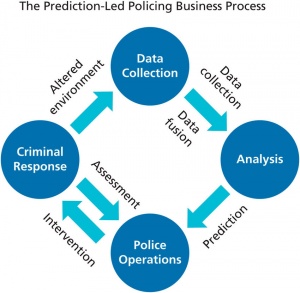

Process

The practice of predictive policing occurs in a cycle consisting of four phases: data collection, analysis, police operations/intervention, and criminal/target response.[1][4] Data collection involves gathering crime data and updating it regularly to reflect current conditions.[4] The second phase, analysis, involves creating predictions on crime occurrences.[1] The third phase, police operations, also called police interventions, involves acting on crime forecasts[1]. The fourth phase, criminal repose, also called target response, refers to law enforcement reacting to the implemented police interventions.[1] This may include the criminals stopping the crimes they are committing, changing locations of where the crime is committed, or changing the way they commit a crime. Thus, making current data unrepresentative of the new environmental conditions, and the cycle begins again.[1]

Efficacy

In 2011, predictive policing was included in the list of the top 50 best inventions, created by TIME magazine.[4] Since then, predictive policing practices have been implemented in cities such as Los Angeles, Santa Cruz, New York City, and others.[5]

Los Angeles Police Department

From 2011 to 2013, a controlled randomized trial on predictive policing was conducted in three divisions, the Foothill Division, North Hollywood Division, Southwest Division, by the Los Angeles Police Department.[6][7] The test group received leads produced by an algorithm on areas to target. The control group received leads produced by an analyst, using current policing techniques. At the end of the study, officers using the algorithmic predictions had an average 7.4% drop in crime at the mean patrol level. The officers using predictions made by the analyst had an average 3.5% decrease in crime at the mean patrol level. [7]. The percent difference in crime rates in these locations in the study was statistically significant, but when results were adjusted for previous crime rates in these locations arrests were actually lower or unchanged. [7]

New York City Police Department

In 2017, researchers analyzed the effectiveness of predictive policing methods since 2013, when the Domain Awareness System (DAS) was implemented in the NYPD. [2] As defined by the researchers, DAS “... is a citywide network of sensors, databases, devices, software, and infrastructure that informs decision making by delivering analytics and tailored information to officers' smartphones and precinct desktops.[8] The evaluation displayed that the overall crime index of New York decreased by 6%, but the researchers do not believe the decrease is entirely attributed to the use of DAS.[8] The DAS has generated a predicted $50 million in sayings for the NYPD per year through increasing staff efficiency. [8]

Shreveport Police Department

Analysis of a predictive policing experiment in the Shreveport Police Department in Louisiana was conducted by RAND (Research and Development) researchers in 2012 [9]. Three police divisions used the analytical predictive policing strategy, called The Predictive Intelligence Led Operational Targeting (PILOT). The three control police divisions used existing policing strategies. There were no statistically significant differences in property crime levels in areas patrolled by the experimental police groups and control police groups.[10]

Ethical Concerns

Statements of concern about predictive policing over civil rights and civil liberties and the debate that algorithms could reinforce racial biases of the criminal justice system[3] have been issued by national organizations like the ACLU and NAACP.[7][11]

The Fourth Amendment

The Fourth Amendment is the constitutional restriction on the U.S. government’s ability to obtain personal or private information. It protects citizens from unreasonable searches and seizures as determined through case law.[1] Law professor Fabio Arcila Jr. claims that predictive policing usage could “... fundamentally undermine the Fourth Amendment’s protections...” have arisen.[12] Predictive policing methods raise specific concern on police-citizen encounters because, “ investigative detentions, or stops, which must be preceded by reasonable, articulable suspicion of criminal activity.”[13]. Andrew G. Ferguson, a law professor at the American University Washington College of Law, explains in a law review that an encounter can “be predicted on the aggregation of specific and individualized, but otherwise noncriminal, factors.” He argues that otherwise noncriminal factors “might create a predictive composite that satisfied the reasonable suspicion standard” as depicted by predictive policing algorithm insights. But researchers Sarah Brayne, Alex Rosenblat, and Danah Boyd think that “... predictive analytics may effectively make it easier to meet the reasonable suspicion standard in practice, thus justifying more police stops.”[4] Overpolicing specific areas brings up ethical concerns that are further discussed later.

Oakland, California Study

A study conducted on 2010 crime data in the city of Oakland, California with the predictive algorithm PredPol to predict daily crime expectations for 2011. The results directed police to target black communities at nearly twice the rate of white, despite public health data displaying roughly equivalent drug usage across races.[14] Similar results were found when analyzing low-income neighborhoods and higher-income neighborhoods. Researchers conducting the study predicted that a bias amplifying feedback loop could be created when non-white and low-income areas are targeted and heavily policed, as suggested by the algorithm. The higher reports of crime will be accounted for in future predictions, and minorities will be further faced with high concentrations of patrol.[14]

Broward County, Florida Study

Another study performed in 2016 by ProPublica investigative journalists analyzed actual outcomes of crimes with predictions made by the algorithm, called COMPAS (Correctional Offender Management Profiling for Alternative Sanctions). It assigns a risk score to a convicted criminal to determine if they will be likely to commit another offense in the next two years, or commit recidivism. [15] Over 7,000 risk scores of individuals arrested in 2013 and 2014 in Broward County, Florida were compared with the offenders’ actual outcomes. The journalist found that black defendants were almost twice (45%) as likely to be misclassified as high risk when compared to white defendants (23%). On the contrary, their analysis had shown that white defendants were mislabeled as low risk almost twice (48%) as often as black defendants (28%).[16]

What Leads to Biased Data

Predictive algorithms in policing are often based off of previous arrest datasets. This is where bias can be introduced. A 2013 study done by the New York Civil Liberties Union found that while black and Latino males between the ages of fourteen and twenty-four made up only 4.7 percent of the city’s population, they accounted for 40.6 percent of the stop-and-frisk checks by police. [17] This pattern of policing minorities disproportionately leads to a disproportionate amount of minorities getting charged with crimes. A key factor in algorithms' determining recidivism is based on past "involvement" with the police, and this is one method where racial bias can be introduced. [18] These algorithms can serve to proliferate racial profiling. Dorothy Roberts also argues that factors that go into these algorithms like incarceration history, level of education, neighborhood of residence, membership in gangs or organized crime groups can produce algorithms that suggest to over-police minority communities or those of a low-income. [19] Further a study of AI has found that policing algorithms can lack feedback loops and can target minority neighborhoods. [20]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Perry, W., Mcinnis, B., Price, C., Smith, S., & Hollywood, J. (2013). Predictive Policing: The Role of Crime Forecasting in Law Enforcement Operations. DOI:10.7249/rr23. Retrieved from https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR233.html

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Meijer, A., & Wessels, M. (2019). Predictive Policing: Review of Benefits and Drawbacks. International Journal of Public Administration, 42(12), 1031-1039. DOI:10.1080/01900692.2019.1575664. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01900692.2019.1575664

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Lau, T. (2020, April 01). Predictive Policing Explained. Retrieved from https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/predictive-policing-explained

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Brayne, S., Rosenblat, A., & Boyd, D. (2015). Predictive Policing. DATA & CIVIL RIGHTS: A NEW ERA OF POLICING AND JUSTICE. Retrieved from https://datacivilrights.org/pubs/2015-1027/Predictive_Policing.pdf.

- ↑ Friend, Z., M.P.P. (2013, April 09). Predictive Policing: Using Technology to Reduce Crime. Retrieved from https://leb.fbi.gov/articles/featured-articles/predictive-policing-using-technology-to-reduce-crime

- ↑ Mohler, G. O., Short, M. B., Malinnowski, S., Johsson, M., Tita, G.E., Bertozzi, A. L., & Brantingham, J. (2015) Randomized Controlled Field Trials of Predictive Policing, Journal of the American Statistical Association, 110:512, 1399-1411, DOI: 10.1080/01621459.2015.1077710. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01621459.2015.1077710

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Brantingham, J., Valasik, M., & Mohler, G. O. (2018) Does Predictive Policing Lead to Biased Arrests? Results From a Randomized Controlled Trial, Statistics and Public Policy, 5:1, 1-6, DOI: 10.1080/2330443X.2018.1438940. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/2330443X.2018.1438940

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Levine, E. S., Tisch, J. S., Tasso, A. S., & Joy, M. S. (2017). The New York City Police Department’s Domain Awareness System: 2016 Franz Edelman Award Finalists [Abstract]. Informs Journal on Applied Analytics, 47(1), 1-109. doi:10.1287/inte.2016.0860. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/312542282_The_New_York_City_Police_Department's_Domain_Awareness_System_2016_Franz_Edelman_Award_Finalists

- ↑ Hunt, P., Saunders, J., & Hollywood, J. S. (2014, July 01). Evaluation of the Shreveport Predictive Policing Experiment. Retrieved from https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR531.html

- ↑ Moses, L. B., & Chan, J.(2018) Algorithmic prediction in policing: assumptions, evaluation, and accountability, Policing and Society, 28:7, 806-822, DOI: 10.1080/10439463.2016.1253695. Retrieved fromhttps://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10439463.2016.1253695

- ↑ Moravec, E. R. (2019, September 10). Do Algorithms Have a Place in Policing? Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2019/09/do-algorithms-have-place-policing/596851/

- ↑ Arcila, F . (2013) Nuance, Technology, and the Fourth Amendment: A Response to Predictive Policing and Reasonable Suspicion, 63 Emory L. J. Online 2071. Retrieved from https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/elj-online/30

- ↑ Ferguson, A. G. (2011). Crime Mapping and the Fourth Amendment: Redrawing “High-Crime Areas ”. Hastings Law Journal, 63(1), 179-232. Retrieved from https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol63/iss1/4.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Ehrenberg, R. (2017, March 8). Data-driven crime prediction fails to erase human bias. Retrieved from https://www.sciencenews.org/blog/science-the-public/data-driven-crime-prediction-fails-erase-human-bias

- ↑ Larson, J., Angwin, J., Mattu, S., & Kirchner, L. (2016, May 23). Machine Bias. Retrieved from https://www.propublica.org/article/machine-bias-risk-assessments-in-criminal-sentencing

- ↑ Angwin, J., Larson, J., Kirchner, L., & Mattu, S. (2016, May 23). How We Analyzed the COMPAS Recidivism Algorithm. Retrieved from https://www.propublica.org/article/how-we-analyzed-the-compas-recidivism-algorithm

- ↑ Bellin, Jeffrey. “The Inverse Relationship between the Constitutionality and Effectiveness of New York City 'Stop and Frisk'.” SSRN, 25 Mar. 2014, papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2413935.

- ↑ O'Neil, C. (2016, June 21). Weapons of Math Destruction. weaponsofmathdestructionbook.com. https://weaponsofmathdestructionbook.com/.

- ↑ Roediger, B. D., & Roberts, D. E. (2019, April 10). Digitizing the Carceral State. Harvard Law Review. https://harvardlawreview.org/2019/04/digitizing-the-carceral-state/.

- ↑ Where in the World is AI? Responsible & Unethical AI Examples. (0AD). https://map.ai-global.org/.