Difference between revisions of "Predictive Policing"

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

==Overview== | ==Overview== | ||

| − | '''Predictive policing''' is a term used to describe the application of analytical techniques on data with the intent to prevent future crime by making statistical predictions. This data includes information about past crimes, the local environment, and other relevant information that can be used to make predictions about crime.<ref name="Perry">Perry, W., Mcinnis, B., Price, C., Smith, S., & Hollywood, J. (2013). Predictive Policing: The Role of Crime Forecasting in Law Enforcement Operations. DOI:10.7249/rr23. Retrieved from https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR233.html </ref> It is not a method for replacing traditional policing practices such as hotspot policing, intelligence-led policing, or problem-oriented policing. It is a way to assist conventional methods by applying the knowledge gained from algorithms and statistical techniques.<ref>Meijer, A., & Wessels, M. (2019). Predictive Policing: Review of Benefits and Drawbacks. International Journal of Public Administration, 42(12), 1031-1039. DOI:10.1080/01900692.2019.1575664. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01900692.2019.1575664</ref> The utilization of predictive policing methods in law enforcement has received criticism that it challenges civil rights and civil liberties, and its algorithms could exacerbate racial biases in the criminal justice system.<ref>Lau, T. (2020, April 01). Predictive Policing Explained. Retrieved from https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/predictive-policing-explained</ref> | + | '''Predictive policing''' is a term used to describe the application of analytical techniques on data with the intent to prevent future crime by making statistical predictions. This data includes information about past crimes, the local environment, and other relevant information that can be used to make predictions about crime.<ref name="Perry">Perry, W., Mcinnis, B., Price, C., Smith, S., & Hollywood, J. (2013). Predictive Policing: The Role of Crime Forecasting in Law Enforcement Operations. DOI:10.7249/rr23. Retrieved from https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR233.html </ref> It is not a method for replacing traditional policing practices such as hotspot policing, intelligence-led policing, or problem-oriented policing. It is a way to assist conventional methods by applying the knowledge gained from algorithms and statistical techniques.<ref name="Meijer">Meijer, A., & Wessels, M. (2019). Predictive Policing: Review of Benefits and Drawbacks. International Journal of Public Administration, 42(12), 1031-1039. DOI:10.1080/01900692.2019.1575664. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01900692.2019.1575664</ref> The utilization of predictive policing methods in law enforcement has received criticism that it challenges civil rights and civil liberties, and its algorithms could exacerbate racial biases in the criminal justice system.<ref>Lau, T. (2020, April 01). Predictive Policing Explained. Retrieved from https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/predictive-policing-explained</ref> |

==In Practice== | ==In Practice== | ||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

===Los Angeles Police Department=== | ===Los Angeles Police Department=== | ||

| − | From 2011 to 2013, a controlled randomized trial on predictive policing was conducted in three divisions, the Foothill Division, North Hollywood Division, Southwest Division, by the Los Angeles Police Department.<ref>Mohler, G. O., Short, M. B., Malinnowski, S., Johsson, M., Tita, G.E., Bertozzi, A. L., & Brantingham, J. (2015) Randomized Controlled Field Trials of Predictive Policing, Journal of the American Statistical Association, 110:512, 1399-1411, DOI: 10.1080/01621459.2015.1077710. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01621459.2015.1077710</ref> | + | From 2011 to 2013, a controlled randomized trial on predictive policing was conducted in three divisions, the Foothill Division, North Hollywood Division, Southwest Division, by the Los Angeles Police Department.<ref>Mohler, G. O., Short, M. B., Malinnowski, S., Johsson, M., Tita, G.E., Bertozzi, A. L., & Brantingham, J. (2015) Randomized Controlled Field Trials of Predictive Policing, Journal of the American Statistical Association, 110:512, 1399-1411, DOI: 10.1080/01621459.2015.1077710. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01621459.2015.1077710</ref><ref name="Brantingham"/> The test group received leads produced by an algorithm on areas to target. The control group received leads produced by an analyst, using current policing techniques. At the end of the study, officers using the algorithmic predictions had an average 7.4% drop in crime at the mean patrol level. The officers using predictions made by the analyst had an average 3.5% decrease in crime at the mean patrol level. <ref name="Brantingham">Brantingham, J., Valasik, M., & Mohler, G. O. (2018) Does Predictive Policing Lead to Biased Arrests? Results From a Randomized Controlled Trial, Statistics and Public Policy, 5:1, 1-6, DOI: 10.1080/2330443X.2018.1438940. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/2330443X.2018.1438940</ref>. The Foothill Division experienced an overall 12% decrease in crime at the end of the study.<ref name="Friend"/> |

| + | ===New York City Police Department=== | ||

| + | In 2017, researchers analyzed the effectiveness of predictive policing methods since 2013, when the Domain Awareness System (DAS) was implemented in the NYPD. <ref name="Meijer"/> As defined by the researchers, DAS “... is a citywide network of sensors, databases, devices, software, and infrastructure that informs decision making by delivering analytics and tailored information to officers' smartphones and precinct desktops.<ref name="Levine">Levine, E. S., Tisch, J. S., Tasso, A. S., & Joy, M. S. (2017). The New York City Police Department’s Domain Awareness System: 2016 Franz Edelman Award Finalists [Abstract]. Informs Journal on Applied Analytics, 47(1), 1-109. doi:10.1287/inte.2016.0860. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/312542282_The_New_York_City_Police_Department's_Domain_Awareness_System_2016_Franz_Edelman_Award_Finalists</ref> The evaluation displayed that the overall crime index of New York decreased by 6%, but the researchers do not believe the decrease is entirely attributed to the use of DAS.<ref name="Levine"/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Shreveport Police Department=== | ||

| + | Analysis of a predictive policing experiment in the Shreveport Police Department in Louisiana was conducted by RAND (Research and Development Organization) researchers in 2012 <ref>Hunt, P., Saunders, J., & Hollywood, J. S. (2014, July 01). Evaluation of the Shreveport Predictive Policing Experiment. Retrieved from https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR531.html</ref>. Three police divisions used the analytical predictive policing strategy, called The Predictive Intelligence Led Operational Targeting (PILOT). The three control police divisions used existing police strategies. There were no statistically significant differences in property crime levels in areas patrolled by the experimental police groups and controlled police groups.<ref>Moses, L. B., & Chan, J.(2018) Algorithmic prediction in policing: assumptions, evaluation, and accountability, Policing and Society, 28:7, 806-822, DOI: 10.1080/10439463.2016.1253695. Retrieved fromhttps://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10439463.2016.1253695 | ||

| + | </ref> | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

Revision as of 12:52, 12 March 2021

Contents

Overview

Predictive policing is a term used to describe the application of analytical techniques on data with the intent to prevent future crime by making statistical predictions. This data includes information about past crimes, the local environment, and other relevant information that can be used to make predictions about crime.[1] It is not a method for replacing traditional policing practices such as hotspot policing, intelligence-led policing, or problem-oriented policing. It is a way to assist conventional methods by applying the knowledge gained from algorithms and statistical techniques.[2] The utilization of predictive policing methods in law enforcement has received criticism that it challenges civil rights and civil liberties, and its algorithms could exacerbate racial biases in the criminal justice system.[3]

In Practice

Predictive policing practices can be divided into four categories: predicting crime, predicting offenders, predicting perpetrator's identities, and predicting victims of crime.[1] It can also be categorized into place-based, which makes geographic predictions on crime, or person-based in which make predictions about individuals, victims, or social groups involved in crime. [4]

Process

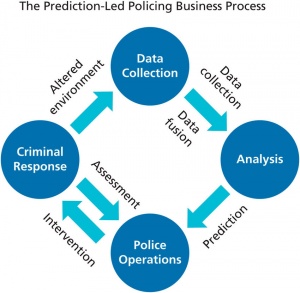

The practice of predictive policing occurs in a cycle consisting of four phases: data collection, analysis, police operations/intervention, and criminal/target response.[1][4] Data collection involves gathering crime data and updating it regularly to reflect current conditions.[4] The second phase, analysis, involves creating predictions on crime occurrences.[1] The third phase, police operations, also called police interventions, involves acting on crime forecasts[1]. The fourth phase, criminal repose, also called target response, refers to law enforcement reacting to the implemented police interventions.[1] This may include the criminals stopping the crimes they are committing, changing locations of where the crime is committed, or changing the way they commit a crime. Thus, making current data unrepresentative of the new environmental conditions, and the cycle begins again.[1]

Efficacy

In 2011, predictive policing was included in the list of the top 50 best inventions, created by TIME magazine.[4] Since then, predictive policing practices have been implemented in cities such as Los Angeles, Santa Cruz, New York City, and others.[5]

Los Angeles Police Department

From 2011 to 2013, a controlled randomized trial on predictive policing was conducted in three divisions, the Foothill Division, North Hollywood Division, Southwest Division, by the Los Angeles Police Department.[6][7] The test group received leads produced by an algorithm on areas to target. The control group received leads produced by an analyst, using current policing techniques. At the end of the study, officers using the algorithmic predictions had an average 7.4% drop in crime at the mean patrol level. The officers using predictions made by the analyst had an average 3.5% decrease in crime at the mean patrol level. [7]. The Foothill Division experienced an overall 12% decrease in crime at the end of the study.[5]

New York City Police Department

In 2017, researchers analyzed the effectiveness of predictive policing methods since 2013, when the Domain Awareness System (DAS) was implemented in the NYPD. [2] As defined by the researchers, DAS “... is a citywide network of sensors, databases, devices, software, and infrastructure that informs decision making by delivering analytics and tailored information to officers' smartphones and precinct desktops.[8] The evaluation displayed that the overall crime index of New York decreased by 6%, but the researchers do not believe the decrease is entirely attributed to the use of DAS.[8]

Shreveport Police Department

Analysis of a predictive policing experiment in the Shreveport Police Department in Louisiana was conducted by RAND (Research and Development Organization) researchers in 2012 [9]. Three police divisions used the analytical predictive policing strategy, called The Predictive Intelligence Led Operational Targeting (PILOT). The three control police divisions used existing police strategies. There were no statistically significant differences in property crime levels in areas patrolled by the experimental police groups and controlled police groups.[10]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Perry, W., Mcinnis, B., Price, C., Smith, S., & Hollywood, J. (2013). Predictive Policing: The Role of Crime Forecasting in Law Enforcement Operations. DOI:10.7249/rr23. Retrieved from https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR233.html

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Meijer, A., & Wessels, M. (2019). Predictive Policing: Review of Benefits and Drawbacks. International Journal of Public Administration, 42(12), 1031-1039. DOI:10.1080/01900692.2019.1575664. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01900692.2019.1575664

- ↑ Lau, T. (2020, April 01). Predictive Policing Explained. Retrieved from https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/predictive-policing-explained

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Brayne, S., Rosenblat, A., & Boyd, D. (2015). Predictive Policing. DATA & CIVIL RIGHTS: A NEW ERA OF POLICING AND JUSTICE. Retrieved from https://datacivilrights.org/pubs/2015-1027/Predictive_Policing.pdf.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Friend, Z., M.P.P. (2013, April 09). Predictive Policing: Using Technology to Reduce Crime. Retrieved from https://leb.fbi.gov/articles/featured-articles/predictive-policing-using-technology-to-reduce-crime

- ↑ Mohler, G. O., Short, M. B., Malinnowski, S., Johsson, M., Tita, G.E., Bertozzi, A. L., & Brantingham, J. (2015) Randomized Controlled Field Trials of Predictive Policing, Journal of the American Statistical Association, 110:512, 1399-1411, DOI: 10.1080/01621459.2015.1077710. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01621459.2015.1077710

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Brantingham, J., Valasik, M., & Mohler, G. O. (2018) Does Predictive Policing Lead to Biased Arrests? Results From a Randomized Controlled Trial, Statistics and Public Policy, 5:1, 1-6, DOI: 10.1080/2330443X.2018.1438940. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/2330443X.2018.1438940

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Levine, E. S., Tisch, J. S., Tasso, A. S., & Joy, M. S. (2017). The New York City Police Department’s Domain Awareness System: 2016 Franz Edelman Award Finalists [Abstract]. Informs Journal on Applied Analytics, 47(1), 1-109. doi:10.1287/inte.2016.0860. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/312542282_The_New_York_City_Police_Department's_Domain_Awareness_System_2016_Franz_Edelman_Award_Finalists

- ↑ Hunt, P., Saunders, J., & Hollywood, J. S. (2014, July 01). Evaluation of the Shreveport Predictive Policing Experiment. Retrieved from https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR531.html

- ↑ Moses, L. B., & Chan, J.(2018) Algorithmic prediction in policing: assumptions, evaluation, and accountability, Policing and Society, 28:7, 806-822, DOI: 10.1080/10439463.2016.1253695. Retrieved fromhttps://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10439463.2016.1253695