Planned Obsolescence

Contents

Introduction

Planned obsolescence is when companies create their products to stop functioning after a certain period of time and are difficult or expensive to repair, in order to sway consumers to purchase an updated product more frequently. There are four types of obsolescence: technological or functional obsolescence, psychological or style obsolescence, systemic obsolescence and obsolescence due to product failure or breakdown [1].

Customers feel deceived by companies that create products commonly used, intuitive to use, and seemingly helpful, when these products break down frequently [2]. Customers spend more money and large corporations continue to get larger and richer.

The frequent upgrade of devices leads to more devices being thrown away. On a large scale, this causes the growth of landfills, further exacerbating climate change and global warming. In 2014, there was 41 million tons of electronic waste. In 2016, there was 45 million tons of electronic waste. Finally, in 2021, there was 52 million tons of electronic waste. Additionally, manufacturing is using an increasing amount of non replenishable raw materials, such as coltan, in order to manually create a battery with a reduced size. Since more and more of these batteries will need to be produced, and since they use nonrenewable resources, these resources will run out sooner than if they were not used to produce electronic parts with short lifespans [3].

Planned obsolescence can also be viewed as a positive aspect of the market and as a part of capitalism. Since new products are constantly being produced, someone needs to produce all of these products. The increasing amount of products leads to an increasing amount of jobs, which is beneficial to the economy. After the 1929 Wall Street Crash, Bernard London, an individual invested in the real estate industry, suggested that planned obsolescence should become a national policy in order to fix the economy. He suggested that all products have a predetermined lifespan and once the products reach that date, they are required to buy a new one. In order to help the customer, who now had to buy a new product, the customer was given the value of the initial item’s sale tax in order to contribute to the cost of the next model of the product [4]. This increased consumption increased the country's gross domestic product, a measurement of the value of goods and services in a country. This helped improve the economy because consumers more frequently purchased items, which in turn made companies have more money and needed to produce more goods and therefore hire more workers. The success of an economy relies on demand for businesses; otherwise, businesses’ products would not be purchased, they would not make money and have to stop making goods and then have to decrease the amount of people they hire due to not having enough money to pay them [5].

Additionally, the increasing amount of products on the market creates competition between companies which encourages the quality of products to increase. If companies did not engage in competition, they would not be incentivized to create new features and better their products. This competition allows new ideas to be shared and new products to be developed [6].

Another way to view planned obsolescence is that it is not actually a strategy used in the economic market, as it would not be beneficial to the manufacturer, or the consumer. It would be harmful to both sides of a sale. This is because companies will want their product to last the longest and perform the best to encourage consumers to purchase the product from their companies as opposed to competitor companies [7].

History

The first time planned obsolescence was seen was in the The Centennial Light Bulb. The Centennial Light bulb has been burning for over one million hours. Nowadays, the average time that a light bulb burns for is between 8,000 and 20,000 hours. This is over 50 times worse performance. The first light bulbs, like the Centennial light bulb, were created from carbon filaments, a much thicker material than the material used in newer light bulbs, metal wires. The change happened because light bulbs became more standard for households, so the companies creating them realized that they would make more money if people bought them more frequently, thus decreasing the quality of the material and decreasing the lifespan [8]. Lightbulbs became a necessity, so when one ran out of light, a consumer had no choice but to purchase another. This business tactic became common practice in many industries, such as automobiles, technology, and fashion.

Different Industries

Automotive

The automobile industry is an industry that has used planned obsolescence to increase sales. In the 1920s, the Chief Executive Officer of General Motors at the time, Alfred Sloan Jr, observed that children frequently wanted new bikes whenever new bikes began to be available in stores. He was inspired to make the car market function similarly [9]. General Motors began creating new models of vehicles more frequently, implementing more design changes and new features in each model. Not long after General Motors began creating models more frequently, they gained much revenue and became the leading manufacturer of automobiles. In order for other automotive manufacturers to compete, they had to adopt this practice as well. This started a trend in the automobile industry that made cars designed so that when a consumer saw a new model on the market, they would want that model over the one they already have [10]. Even before a new car is necessary, in terms of functionality, people want the newest model. Now it is standard that car companies create new models annually. Cars are denoted by the brand of the car and the year it was produced in.

However, automotive companies had to ensure consumers could not see through this new trend in order for customers to continue being loyal and not feel deceived. Companies did this through two methods: constant restyling and by making spare parts rare. Constant restyling refers to changing the way the car looks each year, only by a little. Last years’ model of a car will become “unfashionable,” making people want the newest, “most fashionable” one. This is an example of the “trickle down theory [11],” a common theory in the fashion industry, but applicable to other industries, such as the automobile industry, as well. The trickle down theory analyzes how trends enter and exit society. It states that trends are dependent on class and social levels; trends start at the upper class, the upper class uses it and shows the world that they are using it (often referred to as “influencing”), then the general public finds out about this new product and want to use it because they saw the upper class using it, and they admire the upper classes’ lifestyle and attempt to replicate it in their own. The same psychology applies to individuals wanting the newest car models. The second strategy is making spare parts rare. Car manufacturer companies make parts unavailable at a typical dealership, so when a consumer has a small, insignificant part of their car not functioning, they have the option of searching for a difficult to find and expensive part or buying a new vehicle. This option is also marketed to make the consumer believe that buying an entirely new car will be comparatively cheaper and simpler.

Planned obsolescence in the realm of automotives can be viewed as nonexistent. In the age of the internet, it is simple to look up how long it takes for each car to depreciate. Therefore, it is up to the consumer to choose the vehicle with the longest lifespan, if that is what they prioritize. In 1969, the average car stayed alive for 5.1 years. Now, it is 11.4 years [12]. This shows that the lifespan of cars has increased over time.

In terms of the environmental effects of planned obsolescence in the automotive industry, about ten million vehicles are thrown out each year in the United States. 75% of these cars can be recycled [13] . They will get sent to recycling operations, a center where various parts, including glass, paper, cardboard, plastic, metal, and textiles, are separated and sorted. After this, the materials are able to be reused and made into new products [14]. Metals, batteries, tires, and fluids are parts of vehicles that are generally capable of being recycled. However, there are parts of cars that cannot be recycled and end up in landfills, such as glass. About 3 million tons of car parts that are not recyclable end up in landfills. Automotive manufacturers are also becoming more aware of the effects of global warming on our world and changing policies and materials they produce vehicles with. Companies such as Ford and Mazda are creating vehicles with reused plastic for bumpers. Acura created a model of a car that is 90% recyclable [15].

Now, vehicle manufacturers are working towards becoming more environmentally friendly. Electric cars are gaining popularity. Battery powered cars sales increased by 70 percent in 2021. The sales of gas powered cars decreased by 15 percent in that same time [16]. Additionally, Tesla has created a program that repurposes vehicles batteries into a form of home energy storage [17]. They also update the software of a vehicle to have it be up to date instead of having their customers purchase a new vehicle entirely. This has a stark contrast to companies that make their products unable to get software updates after a couple years.

Technology

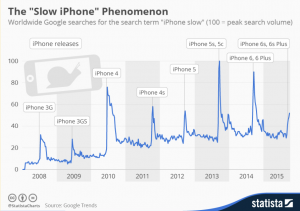

Apple is a company that has been sued for and accused of planned obsolescence numerous times. IPhones are one of Apple's products that are most subject to planned obsolescence. Research shows that whenever a new iPhone is released, the amount of internet searches for “iPhone slow” increases dramatically, indicating that when a new model of the iPhone is released, the old models begin to function at a slower rate [18].

Additionally, iOS 16 was created to only be compatible with iPhones 8 and iPhones created after this. This was created when the iPhone 7 was three years old and still functioning. This left people unable to have up to date software, unable to download certain apps, unable to benefit from new security updates and left without new user experience features. However, Apple justifies the inability of not being able to upgrade to new operating systems with the incompatibility of new features that require different hardware features such as storage, RAM, and processors [20]. Additionally, Apple designs iPhones to have batteries that last two to three years [21] . After this, the battery life is too short so a consumer either has the option to replace it, or buy a new phone. With repairs being difficult to obtain, time consuming, and expensive, consumers often purchase a new phone instead of repairing it. The cost of the repair and the inconvenience of being left without a phone for five to seven business days leaves it so that people think it is more worth it to purchase a new device.

In 2017, Apple was fined by the Italian Competition Authority for ten million euros due to unfair commercial practices. Apple replied to this fine by saying they are purposeful in slowing down devices with software updates, eventually making their device stop working before the hardware stops working, in order to protect consumers from “unforeseen shutdowns [22]” In France, in 2018, a French Environmental Association called ‘Halte à l’obsolescence programmée,’ which translates to ‘Stop planned obsolescence,’ filed a complaint against Apple as well. Their complaint was about iPhones being slowed down through new software updates. Specifically, consumers were unaware of these effects when IOS 10.2.1 and IOS 11.2 were released. This left consumers requiring new batteries or new phones altogether. The iPhone 6, iPhone SE, and iPhone 7 were decreasing in speed by 2018. The iPhone 6 was released in 2014 [23]. The iPhone SE [24] and iPhone 7 were released in 2016 [25]. This shows how shortly after an iPhone was released that it began decreasing in speed. Subsequently, Apple was fined 25 million euros [26].

Samsung also participated in planned obsolescence. When Samsung announced new software updates, they were ambiguous about future results of selecting the update [27]. The software updates resultinly slowed down the speed of the phone. The Italian Competition Authority also fined Samsung five million euros for the same reasons. However, Samsung denied these claims.

Planned Obsolescence Now

While planned obsolescence is not illegal, several organizations are working towards eliminating it. France created a new regulation that requires certain products to publicize their repairability scores to indicate whether they design their products with planned obsolescence in mind. Laptops, lawnmowers, smartphones, TVS and washing machines must have their repairability score public [28]. This score is composed of scores from 5 categories: disassembly capabilities, repair documentation availability, spare part availability, spare part price, and product-specific category that includes software updates, remote repair assistance and more.

The European Union is working towards creating legislation that works to stop planned obsolescence. It is doing this by breaking down the problem into three categories: Unfair Competition and Consumer Protection, Competition Law and Environmental Law.

In regards to Unfair Competition and Consumer Protection, planned obsolescence can violate the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive (UCPD), the Consumers Rights Directive (CRD) or the Consumer Sales and Guarantees Directive (CSGD). European citizens feel as though their rights as a consumer are being infringed upon, believing that businesses who practice planned obsolescence are acting unethically. According to a Eurobarometer survey, 77% of European citizens would prefer to repair a product with new parts, but find that they are essentially forced to replace the product entirely due to repair costs [29].

Competition law relates to protecting consumers in terms of quality, price and choice. Some people argue that planned obsolescence provides consumers with many choices, which is a positive attribute. However, the frequent need to purchase new items may decrease the amount of disposable income consumers have.

Environmental law refers to the waste that is created from disposing of old products. The Waste Framework Directive, when describing the waste hierarchy, states that the following order of waste management is most beneficial to the environment: reuse, then recycle, then recovery, and lastly, disposable. Planned obsolescence increases the amount of waste that is disposed of, which is worst for the environment. In 2015, France created the Energy Transition for Green Growth Act which sought out to decrease environmental pollution. This act stated that planned obsolescence was a criminal offense with a fine of up to 300,000 euros or five percent of the companies average turnover and a possible up to two year prison sentence [30]. Additionally, there are new eco-design rules in the European Union that have had companies take action towards making repairs for products more accessible, so that less products are disposed of, and more are recycled and reused[31].- ↑ Environmental Implications of Planned Obsolescence ... - Tandfonline.com. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/19397038.2015.1099757.

- ↑ Written by: Juliet Ancing | Last updated on Februar, et al. “Planned Obsolescence: The Secret behind Phone Obsolete Too Fast.” CellularNews, 7 Feb. 2023, https://cellularnews.com/mobile-phone/planned-obsolescence/.

- ↑ Iberdrola. “La Obsolescencia Programada y Sus Consecuencias Sobre El Medio Ambiente.” Iberdrola, Iberdrola, 22 Apr. 2021, https://www.iberdrola.com/sustainability/planned-obsolescence.

- ↑ Bisschop, Lieselot, et al. “Designed to Break: Planned Obsolescence as Corporate Environmental Crime - Crime, Law and Social Change.” SpringerLink, Springer Netherlands, 31 Mar. 2022, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10611-022-10023-4.

- ↑ Amadeo, Kimberly. “What You Buy Every Day Drives U.S. Economic Growth.” The Balance, https://www.thebalancemoney.com/consumer-spending-definition-and-determinants-3305917.

- ↑ Written by: Juliet Ancing | Last updated on Februar, et al. “Planned Obsolescence: The Secret behind Phone Obsolete Too Fast.” CellularNews, 7 Feb. 2023, https://cellularnews.com/mobile-phone/planned-obsolescence/.

- ↑ “Here's the Truth about the 'Planned Obsolescence' of Tech.” BBC Future, BBC, https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20160612-heres-the-truth-about-the-planned-obsolescence-of-tech

- ↑ “Here's the Truth about the 'Planned Obsolescence' of Tech.” BBC Future, BBC, https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20160612-heres-the-truth-about-the-planned-obsolescence-of-tech

- ↑ Geiser, Bradley. “How Car Companies Use Planned Obsolescence to Get You to Buy More Cars.” MotorBiscuit, 17 Apr. 2022, https://www.motorbiscuit.com/car-companies-use-planned-obsolescence-consumers-buy-more-cars/.

- ↑ Team, CARRO. “Are Cars Designed to Fail (Planned Obsolescence)?” Carro Blog, 29 May 2020, https://carro.sg/blog/cars-designed-fail-planned-obsolescence/.

- ↑ Graziano, Giada. “What Is the Trickle-down Theory in Fashion?” GLAM OBSERVER, 21 July 2022, https://glamobserver.com/what-is-the-trickle-down-theory-in-fashion/.

- ↑ “Here's the Truth about the 'Planned Obsolescence' of Tech.” BBC Future, BBC, https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20160612-heres-the-truth-about-the-planned-obsolescence-of-tech.

- ↑ DriverSide. “Recyclable Cars: What Parts End up in the Trash?” CNET, CNET, 16 Sept. 2010, https://www.cnet.com/roadshow/news/recyclable-cars-what-parts-end-up-in-the-trash/.

- ↑ Planit, https://www.planitplus.net/JobProfiles/View/767/106.

- ↑ DriverSide. “Recyclable Cars: What Parts End up in the Trash?” CNET, CNET, 16 Sept. 2010, https://www.cnet.com/roadshow/news/recyclable-cars-what-parts-end-up-in-the-trash/.

- ↑ Ewing, Jack, and Peter Eavis. “Electric Vehicles Start to Enter the Car-Buying Mainstream.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 13 Nov. 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/11/13/business/electric-vehicles-buyers-mainstream.html.

- ↑ Vaughn, Mark. “Where Electric Car Batteries Go When They Die.” Autoweek, Autoweek, 1 Nov. 2021, https://www.autoweek.com/news/green-cars/a35803612/battery-recycling/.

- ↑ Richter, Felix. “Infographic: The ‘Slow Iphone’ Phenomenon.” Statista Infographics, 6 Oct. 2015, https://www.statista.com/chart/2514/iphone-releases/.

- ↑ Richter, Felix. “Infographic: The ‘Slow Iphone’ Phenomenon.” Statista Infographics, 6 Oct. 2015, https://www.statista.com/chart/2514/iphone-releases/.

- ↑ McElhearn, Kirk, and Joshua Long. “Apple's Planned Obsolescence: IOS 16, Macos Ventura Drop Support for Many Models.” The Mac Security Blog, 24 Aug. 2022, https://www.intego.com/mac-security-blog/apples-planned-obsolescence/.

- ↑ Team, Wallstreetmojo. “Planned Obsolescence.” WallStreetMojo, 18 June 2022, https://www.wallstreetmojo.com/planned-obsolescence/#h-example-1-apple

- ↑ Bisschop, Lieselot, et al. “Designed to Break: Planned Obsolescence as Corporate Environmental Crime - Crime, Law and Social Change.” SpringerLink, Springer Netherlands, 31 Mar. 2022, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10611-022-10023-4.

- ↑ “IPhone 6.” Apple Wiki, https://apple.fandom.com/wiki/IPhone_6.

- ↑ “IPhone SE (1st Generation).” Apple Wiki, https://apple.fandom.com/wiki/IPhone_SE_(1st_generation).

- ↑ “IPhone 7 Plus.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., https://www.britannica.com/topic/iPhone-7-Plus.

- ↑ Bisschop, Lieselot, et al. “Designed to Break: Planned Obsolescence as Corporate Environmental Crime - Crime, Law and Social Change.” SpringerLink, Springer Netherlands, 31 Mar. 2022, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10611-022-10023-4.

- ↑ Malinauskaite, Jurgita, and Fatih Buğra Erdem. “Planned Obsolescence in the Context of a Holistic Legal Sphere and the Circular Economy.” Oxford Journal of Legal Studies, vol. 41, no. 3, 2021, pp. 719–749., https://doi.org/10.1093/ojls/gqaa061.

- ↑ Hirsh, Sophie. “Planned Obsolescence Exposed at Apple and Microsoft, in Light of New French Regulations.” Green Matters, Green Matters, 7 Apr. 2021, https://www.greenmatters.com/p/planned-obsolescence

- ↑ Malinauskaite, Jurgita, and Fatih Buğra Erdem. “Planned Obsolescence in the Context of a Holistic Legal Sphere and the Circular Economy.” Oxford Journal of Legal Studies, vol. 41, no. 3, 2021, pp. 719–749., https://doi.org/10.1093/ojls/gqaa061.

- ↑ Malinauskaite, Jurgita, and Fatih Buğra Erdem. “Planned Obsolescence in the Context of a Holistic Legal Sphere and the Circular Economy.” Oxford Journal of Legal Studies, vol. 41, no. 3, 2021, pp. 719–749., https://doi.org/10.1093/ojls/gqaa061.

- ↑ Malinauskaite, Jurgita, and Fatih Buğra Erdem. “Planned Obsolescence in the Context of a Holistic Legal Sphere and the Circular Economy.” Oxford Journal of Legal Studies, vol. 41, no. 3, 2021, pp. 719–749., https://doi.org/10.1093/ojls/gqaa061.