Parasocial Relationship

Parasocial relationships are one-sided relationships occurring between media users and the media they consume.[1] Parasocial relationships typically occur between a viewer and a celebrity. Common examples include, a student and a college athlete, a young child and a teenage heartthrob, and everything in between.

Through a combination of physical performance (talking informally, addressing the viewers in a conversational tone) and digital performance (posting photos that encourage audience engagement, commenting on posts, etc.) the audience are led to believe that the celebrity and them have an interpersonal relationship creating an illusion of intimacy. The ethics of parasocial relationships are similar to those of truth in performance.

Contents

History

The formation of parasocial relationships can be dated back to the existence of humanity. In which individuals formed bonds with popular figures both real and imaginary, such as politicians, gods, and spirits.[2] Entertainment also provided a source of parasocial relationships as audiences bonded with their favorite characters in plays, films, and television. The extent of parasocial relationships developed as time went on and media sites became more prevalent in society.

Despite its longevity, the term parasocial relationship was only coined by sociologists in 1956.[2] They noted that audiences would act as though they were involved in a social relationship with their idols, despite never having met them. The sociologists initially speculated that this was due to a lack of social interaction, but this was later refuted.[2] Today, the standard view on parasocial relationship formation is that they are closely related to friendship formation.[3]

How do parasocial relationships form?

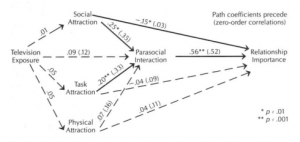

Forming a parasocial relationship is similar to forming a real friendship.[3] At the start of new friendships, frequent, regular communication reduces uncertainty between two parties. This reduction then increases the frequency and regularity of communication and leads to interpersonal attraction. Finally, the positive correlation between interpersonal attraction and intimacy causes the the two people to become closer.

This cycle is easily translatable to media. Audiences are regularly exposed to a personality by consuming their media, increasing the personality's appeal. This exposure attracts audiences to the personalities; eventually, audiences perceive themselves to be in an intimate relationship with the personality, despite the two parties having never interacted.[3] The main difference is this relationship is one sided. The audience can try for communication but it is unlikely the celebrity will reply, which can lead to a great obsession.

In the information age, parasocial relationships are propagated by the changing nature of friendship itself. Rather than engaging with friends solely through face-to-face interactions, friends also perform themselves online, interact digitally with the online-counterparts of their friends by liking and commenting on each other’s’ posts, responding to messages and posting videos.[3] Many friends even limit their interactions to exclusively digital ones. The blur between digital and real-life interaction has made it easier than ever for personalities to perform friend-like interactions. With this friendship culture, it is easy to mask a parasocial relationship with a real one. Creating posts, pictures, liking fan activity, and sending fan messages is far less labor-intensive than real-life relationship cultivation, and personalities can use bots, social media assistants, and other services to perform engagement with audiences to further propagate the parasocial relationship.

Ethics

The ethics of parasocial relationships exist at the boundary of the ethics of performance and truth.

In Stanislavsky's[4] view of performance, truth is a relationship between an actor and the audience. In Hamlet, though everyone knows that there are no such things as ghosts, audiences and actors both suspend their belief, acting and reacting as if the ghost of Hamlet's father were real in order to enhance their enjoyment of the play. The suspension of disbelief is dependent on the audience's willingness to do so, as well as the actor's ability to convey the emotional truth required in the situation. If a performance is good, audiences and actors are moved to emotional connection. If a performance is bad, the connection doesn't exist or is poorly forged.

When applied parasocial relationships, personalities also do not have to be authentic; however, they must be skilled at encouraging audiences to suspend their disbelief and instead believe that their media interactions are genuine. For example, a YouTuber might be paid $70,000 to perform a negative product review. The success of this performance depends on the YouTuber's ability to convey the emotional truth of disliking this product - and that nobody disclose that he was paid for it. In this case, while makeup influencer MannyMUA was able to create a semi-authentic video performing his hatred of makeup product Lashify, news leaked that he had been paid handsomely by a competing company (Lilly Lashes) to do so. This shattered the audience's ability to believe his performed hatred of the product.[5]

The difference between a social-media performance and a real-life performance is the consequences. A bad theatrical performance garners a bad review, and potentially causes the actor to lose some work. A bad social-media performance garners mass-scale online public shaming. MannyMUA received extreme backlash when news of Lilly Lashes' $70,000 "sponsorship" leaked. This in combination with other scandals ultimately led him to lose half a million subscribers.[6]

"Effective" and "Ineffective" Performances

From this examination of parasocial relationships from a performance-ethics standpoint, it can be concluded that an effective performance is dependent on (1) the influencer's ability to generate suspension of audience disbelief and (2) that no conflicting outside information emerge otherwise. This is highly related to the influencer's ability to encourage both primary and secondary trust in a virtual environment.[7] Primary trust is the trustworthiness of an individual from a factual point of view: are they being honest? Secondary trust is the belief that the other "cherishes one’s esteem" and will "reply to an act of trust in kind (‘trust-responsiveness’)."[7] Thus, primary trust is generated by Factor 2, while secondary trust is generated by Factor 1. Effective performances create both primary and secondary trust. Ineffective performances broach primary trust as directly conflicting information emerges. This then leads audiences to doubt their secondary trust in the influencer and perceive them as fake.

It should be noted that the parasocial relationships are just one of the many ways that audiences interact with their media personalities. Thus, influencers with effective parasocial performances might not necessarily have more fans or financial success than influencers with ineffective parasocial performances. In other words, one can have an ineffective parasocial performance and still be successful, as evidenced by many real-life figures.

Effective Influencers

These influencers tend to be intentional in the types of content they create. They are aware of their parasocial relationships with their audiences and ensure that no conflicting outside information can be used to sabotage their credibility.

Oliver Thorn / PhilosopyTube

Oliver "Ollie" Thorn is a British Actor and YouTuber of the channel PhilosophyTube, which explores everyday phenomena and social issues through a philosophical lens. Viewers cultivated a parasocial relationship with Thorn as an internet-friendly, humorous philosophy professor. Their parasocial relationship deepened when Thorn opened up in his video titled "Suic!de and Ment@l He@lth,"[8] in which Thorn explored the philosophy of mental illness and patient rights while revealing that he to struggled with depression.

Following this video, Thorn's YouTube viewership and Patreon donations increased substantially.[9] Thorn later analyzed the parasocial relationship between him and his fans in a second video, concluding that YouTube is a performance. Through his videos, Thorn convinced his audience to suspend their disbelief that they were merely staring at a computer screen, and to instead believe that Thorn was a cosmonaut having a life-threatening suicidal breakdown or a YouTuber being interrogated by Scotland Yard for the crime of "deceiving" his audiences. The authenticity of these situations cannot be threatened by outside information because they were exaggerated to begin with - everyone knows that Thorn is neither cosmonaut nor criminal. Audiences instead connect with the emotional truths in those situations - feeling hopeless and overcome with depression or feeling conflicted and unsure of what truth means when one is a public persona - while learning philosophy.

Natalie Wynn / Contrapoints

Natalie Wynn[10] is a self-titled "ex-philosopher" and transgender YouTuber whose channel similarly examines social issues. Viewers cultivated a parasocial relationship with Wynn through her penchant to perform as highly exaggerated personas, as well as her highly-public gender transition. Similar to Thorn, Wynn uses the exaggerated approach, birthing characters with colorful hair, long nails, and outrageous attitudes to ensure that her authenticity cannot be questioned in midst of all of the exaggeration.

For superfans of Wynn and Thorn, another aspect of their parasocial relationship lies in the "ship" between them. Similar to 'ships' in Fan fiction, fans are obsessed with the idea of a potential relationship between ContraPoints and PhilosophyTube because they have good chemistry on camera and produce videos on similar topics. Wynn and Thorn encourage this ship by performing it on their YouTube accounts by flirting with each other in the comments.[11] They also perform it on other platforms.[12]

Marlena Stell

Marlena Stell is a makeup influencer and founder of cosmetics company Makeup Geek. As an influencer, stell cultivates a parasocial relationship with her audience by presenting herself as a relatable, confident woman trying to navigate the complexities of makeup, fashion, and life. She is one of the early influencers of the YouTube Beauty Community.

Stell is intentional about the parasocial relationship she has with her audience, aiming to inspire all women.[13] She increased her authenticity by creating a video titled "My truth regarding the beauty community," detailing all of the dishonest, manipulative, and greedy tactics that influencers do behind their fans' backs with a logical, mature approach. Though Stell was attacked by fellow influencers, she stood behind her arguments, thereby performing consistency and integrity in her beliefs. Following this video, Stell gained about 25 thousand subscribers, indicating that fans resonated with her message and positively responded to their enhanced parasocial relationship.[14]

Ineffective Influencers

These influencers tend to not be as aware about the parasocial relationship they have with their audiences. They thus say, do, or create content that spurs controversy and undermines their authenticity.

Olivia Jade

Olivia Jade Gianulli is a 19-year-old influencer. Her young, mostly-female viewers cultivated a parasocial relationship with Gianulli due to a combination of her down-to-earth personality and her luxurious lifestyle, which made audiences feel like they could be her best friend despite their differences. Comments on Gianulli's Instagram[15] showcase this attitude, with young women commenting "Beautiful!" and "You are amazing and gorgeous!" while others asked her where to get her dress and other clothing items she wore.

Gianulli's parasocial personality as a relatable, rich friend fell apart in light of the college-cheating scandal.[16] Fans felt slapped in the face by her involvement in such a large scandal, the fact that she was so privileged and that her family was able to buy her way into USC. She was no longer the relatable friend they had come to know.

As a result of this backlash Gianulli has disabled comments on her YouTube channel. She has also lost many valuable brand deals and is possibly facing expulsion from USC.[17]

Logan Paul

Logan Paul is a 22-year-old American YouTuber and vlogger known for his comedic antics and pranks. As a personality, he performs as the male-counterpart to Gianulli; if she's relatable to young women, then he's relatable to young men. Though his antics have always been brash and abrasive, they resonated with his audiences, who found them humorous. He thus cultivates a parasocial relationship by appealing to his demographic.

In January of 2018, Paul uploaded a video titled "We found a dead body in the Japanese Suicide Forest…", in which he filmed a dead body, "holds back a laugh and says, 'this was all going to be a joke; why did it become so real?'"[18] This video negatively affected his parasocial relationship with his audience, who felt that despite Paul's brash antics, laughing at a dead body proved to be too much. Paul claims he lost approximately $5 million in revenue following the controversy and has since apologized many times and changed the nature of his content to be less abrasive.[19]

References

- ↑ Stanislavsky, K., & Hapgood, E. R. (2014). An actor prepares. Bloomsbury.

- ↑ Martineau, P. (2018, November 19). Inside the Pricey War to Influence Your Instagram Feed. Retrieved from https://www.wired.com/story/pricey-war-influence-your-instagram-feed/.

- ↑ Mannymua733 YouTube Stats, Channel Statistics.(n.d.). Retrieved from https://socialblade.com/youtube/user/mannymua733.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 de Laat, P.B. Ethics Inf Technol (2005) 7: 167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10676-006-0002-6.

- ↑ Thorn, O. (2018, September 28). Suic!de and Ment@l He@lth. Retrieved March 28, 2019, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eQNw2FBdpyE.

- ↑ ContraPoints. (n.d.). ContraPoints. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/user/ContraPoints

- ↑ Wynn, N. (2018, May 02). Jordan Peterson. Retrieved March 29, 2019, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4LqZdkkBDas&t=574s.

- ↑ Wynn, N. (2019, February 10). Natalie Wynn on Instagram: "I trapped a nice English boy into showing me around Edinburgh. Retrieved from https://www.instagram.com/p/BttG1GFBrFs/.

- ↑ Stell, M. (n.d.).Marlena Stell. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/user/MakeupGeekTV/about

- ↑ MakeupGeekTV YouTube Stats, Channel Statistics. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://socialblade.com/youtube/user/makeupgeektv.

- ↑ Gianulli, O. J. (n.d.). OLIVIA JADE on Instagram: "party pants". Retrieved from https://www.instagram.com/p/BcypviSFS6q/.

- ↑ McCarthy, T. (2019, March 14). Lori Loughlin's kid Olivia Jade had 'fun' doling out college admissions advice days before mom's scandal. Retrieved March 28, 2019, from https://www.foxnews.com/entertainment/lori-loughlins-daughter-olivia-jade-talked-about-college-admissions-with-fans-days-before-moms-scandal-broke

- ↑ Spangler, T. (2019, March 15). Olivia Jade, Lori Loughlin's Daughter, Stands to Lose Brand Deals Over College-Admissions Scandal. Retrieved from https://variety.com/2019/digital/news/olivia-jade-lori-loughlin-college-scam-influencer-brand-deals-1203162624/

- ↑ Kidwell, E. (2018, January 11). Logan Paul (and the internet) need to stop treating Japan as clickbait. Retrieved from https://www.theverge.com/2018/1/11/16875188/logan-paul-aokigahara-suicide-forest-japan.

- ↑ Locklear, M. (2019, February 22). Logan Paul hit new lows in 2018, but it doesn't seem to matter. Retrieved from https://www.engadget.com/2019/01/02/logan-paul-new-lows-2018-doesnt-matter/.