Difference between revisions of "Misinformation on WeChat"

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

==Causes== | ==Causes== | ||

===Partisan Outlets=== | ===Partisan Outlets=== | ||

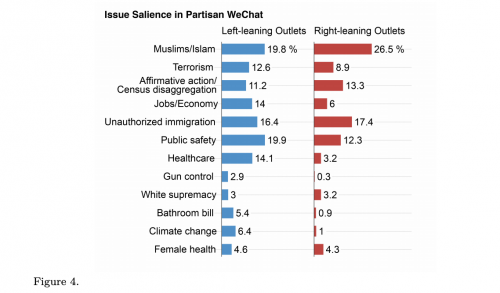

| − | The presence of partisan news outlets on WeChat helps contribute to the asymmetrical polarization, with right-wing outlets producing more articles per month and drawing significantly more views than left-wing outlets. Since these are ethnic media outlets, news that is reported specifically is of interest to Chinese Americans. Misinformation becomes easily spread when popular topics in WeChat don’t align with topics on mainstream English or Chinese speaking media. Some of these topics include affirmative action, undocumented immigration, and Muslims/Islam. This happens because when there is no prominent or mainstream reporting of especially salient topics on WeChat, there is a lack of counternarratives and fact-checking.<ref name = "Columbia"/> | + | The presence of partisan news outlets on WeChat helps contribute to the asymmetrical polarization, with right-wing outlets producing more articles per month and drawing significantly more views than left-wing outlets. Since these are ethnic media outlets, news that is reported specifically is of interest to Chinese Americans. Misinformation becomes easily spread when popular topics in WeChat don’t align with topics on mainstream English or Chinese speaking media. Some of these topics include affirmative action, undocumented immigration, and Muslims/Islam. This happens because when there is no prominent or mainstream reporting of especially salient topics on WeChat, there is a lack of counternarratives and fact-checking.<ref name = "Columbia"/> |

| + | [[File:Issuesalience.png|500px|thumb|center|Issue Salience Among Left vs Right Outlets on WeChat<ref name = "Columbia"/> ]] | ||

===Curation=== | ===Curation=== | ||

Another contributor to WeChat’s misinformation problem is due to its relatively algorithm-less design. Users encounter content by either subscribing directly to news accounts, a chronologically sorted news feed where content is shared by friends, and circulated in invite-only groups. This type of curation makes information flow very socially driven, as information is shared by organically created, trusted networks and not suggested to the user. Out of both personally and socially curated content, social curation plays a larger role in information exposure. In a study conducted by the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia, 87% of respondents who are WeChat users read articles posted by friends, 79% read articles from private groups, and 57% actively read from their subscribed news accounts.<ref name = "Columbia"/> These private groups can range from tight-knit group chats to a form more like Facebook groups, where large groups are topically driven or members loosely have something in common. The larger groups are constantly evolving and splitting to form narrower and narrower echo chambers, where misinformation easily spreads unchecked. This decentralized format in combination with the attention economy allows for clickbait headlines, emotional hysteria, editorializing, and lack of source checking to run rampant.<ref name = "Columbia"/> On top of this, Wechat is entirely dependent on individual users to report false information, providing ideal conditions for misinformation to breed. | Another contributor to WeChat’s misinformation problem is due to its relatively algorithm-less design. Users encounter content by either subscribing directly to news accounts, a chronologically sorted news feed where content is shared by friends, and circulated in invite-only groups. This type of curation makes information flow very socially driven, as information is shared by organically created, trusted networks and not suggested to the user. Out of both personally and socially curated content, social curation plays a larger role in information exposure. In a study conducted by the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia, 87% of respondents who are WeChat users read articles posted by friends, 79% read articles from private groups, and 57% actively read from their subscribed news accounts.<ref name = "Columbia"/> These private groups can range from tight-knit group chats to a form more like Facebook groups, where large groups are topically driven or members loosely have something in common. The larger groups are constantly evolving and splitting to form narrower and narrower echo chambers, where misinformation easily spreads unchecked. This decentralized format in combination with the attention economy allows for clickbait headlines, emotional hysteria, editorializing, and lack of source checking to run rampant.<ref name = "Columbia"/> On top of this, Wechat is entirely dependent on individual users to report false information, providing ideal conditions for misinformation to breed. | ||

| Line 17: | Line 18: | ||

==Efforts to Combat Misinformation== | ==Efforts to Combat Misinformation== | ||

Some groups such as the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinese_Progressive_Association_(San_Francisco) Chinese Progressive Association] and NoMelonGroup are attempting to debunk some of the false stories spread on WeChat with posts containing official sources and combat sensationalized stories with counter-narratives. However, these efforts remain overshadowed by the misinformation itself and are not viewed nearly as much as the original article. Faced with the asymmetric polarization of the app along with the social curation method of content sharing, this information is at a disadvantage in being spread as widely and quickly as more provocative misinformation.<ref name = "Columbia"/><ref name = "propublica"/> | Some groups such as the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinese_Progressive_Association_(San_Francisco) Chinese Progressive Association] and NoMelonGroup are attempting to debunk some of the false stories spread on WeChat with posts containing official sources and combat sensationalized stories with counter-narratives. However, these efforts remain overshadowed by the misinformation itself and are not viewed nearly as much as the original article. Faced with the asymmetric polarization of the app along with the social curation method of content sharing, this information is at a disadvantage in being spread as widely and quickly as more provocative misinformation.<ref name = "Columbia"/><ref name = "propublica"/> | ||

| + | [[File:flyer.png|300px|thumb|center|A flyer created by the Chinese Progressive Association to Debunk Riot Rumors<ref name = "propublica"/>]] | ||

==White House Response, Potential Ethical Implications== | ==White House Response, Potential Ethical Implications== | ||

In response to not only the glut of misinformation, but also concerns about censorship and data collection on the app, the former presidential administration had spearheaded banning the app. Those opposed to the ban cited First Amendment rights as a reason why the action would be ethically ambiguous.<ref name = "wapo">“Chinese censorship invades the U.S. via WeChat” (7 January 2021. Retrieved on 10 March 2021.), [https://academiccommons.columbia.edu/doi/10.7916/D8FB6KCR]</ref> Users of the app are on it to stay connected with relatives and friends in China, where multiple Western social media outlets are banned. George Shen, a technology executive in the Boston area, argues that the free existence of WeChat is a threat to the First Amendment itself, as the extent of the false information muffles free speech and discourse.<ref name = "wapo"/> The question of whether the existence of echo chambers dug within WeChat spreading misinformation swings more towards a right of free speech or an abuse of it remains central to the debate. | In response to not only the glut of misinformation, but also concerns about censorship and data collection on the app, the former presidential administration had spearheaded banning the app. Those opposed to the ban cited First Amendment rights as a reason why the action would be ethically ambiguous.<ref name = "wapo">“Chinese censorship invades the U.S. via WeChat” (7 January 2021. Retrieved on 10 March 2021.), [https://academiccommons.columbia.edu/doi/10.7916/D8FB6KCR]</ref> Users of the app are on it to stay connected with relatives and friends in China, where multiple Western social media outlets are banned. George Shen, a technology executive in the Boston area, argues that the free existence of WeChat is a threat to the First Amendment itself, as the extent of the false information muffles free speech and discourse.<ref name = "wapo"/> The question of whether the existence of echo chambers dug within WeChat spreading misinformation swings more towards a right of free speech or an abuse of it remains central to the debate. | ||

Revision as of 04:39, 12 March 2021

WeChat is an ethnic media hotspot, delivering media produced by and for a specific ethnic group. In this case, Chinese Americans, many of whom are first generation immigrants who downloaded the app with the intention of using it to keep in touch with relatives abroad. Parallel to the spread of misinformation targeting older adults on Facebook, a similar phenomenon is occurring through WeChat. This is possible in part due to the curation method of the app that leads to asymmetric polarization. [1]

Contents

Causes

Partisan Outlets

The presence of partisan news outlets on WeChat helps contribute to the asymmetrical polarization, with right-wing outlets producing more articles per month and drawing significantly more views than left-wing outlets. Since these are ethnic media outlets, news that is reported specifically is of interest to Chinese Americans. Misinformation becomes easily spread when popular topics in WeChat don’t align with topics on mainstream English or Chinese speaking media. Some of these topics include affirmative action, undocumented immigration, and Muslims/Islam. This happens because when there is no prominent or mainstream reporting of especially salient topics on WeChat, there is a lack of counternarratives and fact-checking.[1]

Curation

Another contributor to WeChat’s misinformation problem is due to its relatively algorithm-less design. Users encounter content by either subscribing directly to news accounts, a chronologically sorted news feed where content is shared by friends, and circulated in invite-only groups. This type of curation makes information flow very socially driven, as information is shared by organically created, trusted networks and not suggested to the user. Out of both personally and socially curated content, social curation plays a larger role in information exposure. In a study conducted by the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia, 87% of respondents who are WeChat users read articles posted by friends, 79% read articles from private groups, and 57% actively read from their subscribed news accounts.[1] These private groups can range from tight-knit group chats to a form more like Facebook groups, where large groups are topically driven or members loosely have something in common. The larger groups are constantly evolving and splitting to form narrower and narrower echo chambers, where misinformation easily spreads unchecked. This decentralized format in combination with the attention economy allows for clickbait headlines, emotional hysteria, editorializing, and lack of source checking to run rampant.[1] On top of this, Wechat is entirely dependent on individual users to report false information, providing ideal conditions for misinformation to breed.

Affected Users

The sharing of misinformation disproportionately targets older Asian Americans. There has been a recent rise of conservatism among first generation Chinese immigrants. 35% of Chinese Americans supported Trump in 2016, with this statistic being higher with first generation immigrants.[2]

Recent Examples of Misinformation

- Nearing the 2020 presidential election, a flyer was being spread around claiming that the U.S. Department of Homeland Security was dispatching the National Guard and military to control riots on election day.[3]

- Information about a mainstream media coverup of Joe Biden and his son Hunter Biden was also circulated, they were allegedly being investigated for racketeering and charges.[3]

Efforts to Combat Misinformation

Some groups such as the Chinese Progressive Association and NoMelonGroup are attempting to debunk some of the false stories spread on WeChat with posts containing official sources and combat sensationalized stories with counter-narratives. However, these efforts remain overshadowed by the misinformation itself and are not viewed nearly as much as the original article. Faced with the asymmetric polarization of the app along with the social curation method of content sharing, this information is at a disadvantage in being spread as widely and quickly as more provocative misinformation.[1][3]

White House Response, Potential Ethical Implications

In response to not only the glut of misinformation, but also concerns about censorship and data collection on the app, the former presidential administration had spearheaded banning the app. Those opposed to the ban cited First Amendment rights as a reason why the action would be ethically ambiguous.[4] Users of the app are on it to stay connected with relatives and friends in China, where multiple Western social media outlets are banned. George Shen, a technology executive in the Boston area, argues that the free existence of WeChat is a threat to the First Amendment itself, as the extent of the false information muffles free speech and discourse.[4] The question of whether the existence of echo chambers dug within WeChat spreading misinformation swings more towards a right of free speech or an abuse of it remains central to the debate.- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 “WeChatting American Politics: Misinformation, Polarization, and Immigrant Chinese Media” (15 May 2018. Retrieved on 9 March 2021.), [1]

- ↑ “2016 Post-Election National Asian American Survey” (16 May 2017. Retrieved on 11 March 2021.), [2]

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 “Misinformation Image on WeChat Attempts to Frighten Chinese Americans Out of Voting” (2 November 2020. Retrieved on 9 March 2021.), [3]

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 “Chinese censorship invades the U.S. via WeChat” (7 January 2021. Retrieved on 10 March 2021.), [4]