Difference between revisions of "Misinformation on WeChat"

(→Efforts to Combat Misinformation) |

(→WeChat Fake News Feature) |

||

| Line 34: | Line 34: | ||

=== WeChat Fake News Feature === | === WeChat Fake News Feature === | ||

| − | In 2017, WeChat released a new feature that warns users if a news item circulating on its app is potentially fake or is a rumor. However, the people who deem it to be fake are typically Chinese censors or police. The feature is also gamified by giving users certain perks or points by reading more "rumour-debunking" articles. | + | In 2017, WeChat released a new feature that warns users if a news item circulating on its app is potentially fake or is a rumor. However, the people who deem it to be fake are typically Chinese censors or police. The feature is also gamified by giving users certain perks or points by reading more "rumour-debunking" articles. <ref> "WeChat launches new feature to fight fake news |

| + | ".(2017, June 11). The Indian Express. Retrieved April 1st, 2021 from https://indianexpress.com/article/technology/social/wechat-launches-new-feature-to-fight-fake-news-4698482/ | ||

| + | </ref> | ||

==White House Response, Potential Ethical Implications== | ==White House Response, Potential Ethical Implications== | ||

Revision as of 22:59, 31 March 2021

WeChat is an ethnic media hotspot, delivering media produced by and for a specific ethnic group. In this case, Chinese Americans, many of whom are first-generation immigrants who downloaded the app with the intention of using it to keep in touch with relatives abroad. Parallel to the spread of misinformation targeting older adults on Facebook, there has been a similar phenomenon occurring through WeChat. This trend has in part been attributed to the curation method of the app which leads to asymmetric polarization. [1]

Contents

Background

Due to China’s Great Firewall, most mainstream social media platforms are unavailable in China without the use of a VPN. Because of this, WeChat is one of the main social media platforms in the country. Not only that, but it is one of the few applications that can be used both in China and outside of China. However, WeChat contains many features outside of just messaging. WeChat is also capable of handling monetary transactions between users, similar to Venmo. In addition, it also provides resources for those with language barriers. These two are just some of the functions that have contributed to WeChat's popularity. WeChat has been described as a “super app” that has functions that span many different applications that are used in America.[2]

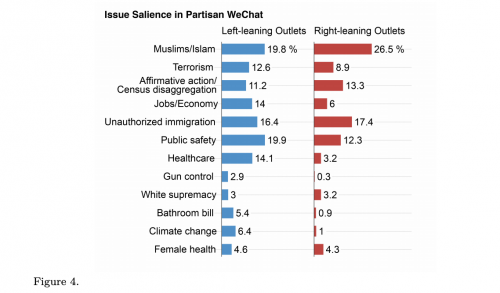

Partisan Outlets

The asymmetrical polarization on the app has been investigated to be attributed to the presence of partisan news outlet accounts. Right-wing outlets produce more articles per month and draw significantly more views than left-wing outlets. Since these are ethnic media outlets, news that is reported specifically is more catered towards the interest of Chinese Americans. Misinformation has become more often spread when popular topics in WeChat haven’t aligned with topics on mainstream English or Chinese speaking media. Some of these topics include affirmative action, undocumented immigration, and Muslims/Islam. A lack of counternarratives and fact-checking has contributed to the spread of misinformation due to no prominent or mainstream reporting on the salient topics circulating on WeChat.[1]

Curation

WeChat's relatively algorithm-less design has also been a center of focus as a reason behind facilitation of misinformation on the app. Users encounter content by either subscribing directly to news accounts, a chronologically sorted news feed where content is shared by friends, and circulated in invite-only groups. This type of curation causes information flow to be very socially driven, as information is shared by organically created, trusted networks and not suggested to the user. Out of both personally and socially curated content, social curation plays a larger role in information exposure. In a study conducted by the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia, 87% of respondents who are WeChat users read articles posted by friends, 79% read articles from private groups, and 57% actively read from their subscribed news accounts.[1] These private groups can range from tight-knit group chats to a form more like Facebook groups, where large groups are topically driven or members loosely have something in common. The larger groups frequently evolve and split to form narrower and narrower 'echo chambers,' where misinformation has been observed to spread without much reservation. This decentralized format in combination with the attention economy has allowed for clickbait headlines, emotional hysteria, editorializing, and lack of source checking to run rampant.[1] On top of this, Wechat entirely depends on individual users to report false information, leading to conditions where misinformation has bred.

Censorship

Unlike social media in the United States, WeChat is heavily regulated by the Chinese government. One of the methods used for censoring content on WeChat is the search of keywords.[3] Any article, post, or message posted on WeChat can be censored through the searching of keywords.[2] In addition, any individual or group that speaks out against the Chinese government on WeChat can also face consequences.[4]

Another form of censorship on WeChat that the Chinese government has used is stopping the media from exposing misinformation. Surveillance of the media originally started because of the messaging of the Communist Party and President Xi Jinping. Suspicions around the 'propaganda' being put out were raised by the public and were investigated by the media. Despite ongoing investigations, the media has had limited power and access to information under the Chinese government.[5]

Affected Users

The sharing of misinformation has been observed to disproportionately target older Asian Americans. The recent rise of conservatism among first-generation Chinese immigrants has run parallel to this. 35% of Chinese Americans supported Trump in 2016, with this statistic being higher with first-generation immigrants.[6]

Recent Examples of Misinformation

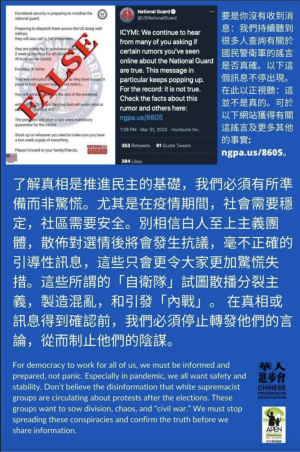

- Nearing the 2020 presidential election, a flyer spread around with claims that the U.S. Department of Homeland Security was dispatching the National Guard and military to control riots on election day.[7]

- Information about a mainstream media coverup of Joe Biden and his son Hunter Biden was also circulated, with statements that they were allegedly being investigated for racketeering and charges.[7]. A media network found that Steve Bannon has been working with billionaire funder Guo Wengui to circulate these false stories about the Biden family. These attacks were not just a few people; they were coordinated, specialized attacks organized using a Discord chat group. Members of each group tweeted links to alleged sex tapes that showed Hunter Biden using drugs on a visit to Beijing. Soon after, Twitter suspended these accounts linked to Guo and these anonymous followers of his. [8]

Efforts to Combat Misinformation

Some groups such as the Chinese Progressive Association and NoMelonGroup are attempting to debunk some of the false stories spread on WeChat with posts containing official sources and combat sensationalized stories with counter-narratives. However, these efforts remain overshadowed by the misinformation itself and are not viewed nearly as much as the original article. Faced with the asymmetric polarization of the app along with the social curation method of content sharing, these groups feel that their information is at a disadvantage in being spread as widely and quickly as more provocative misinformation.[1][7]

Another group that is continually helping to combat right-wing WeChat disinformation are Liberal Chinese Americans. According to Foreign Policy, in the weeks leading up to 2020 election, many liberal accounts published a "plethora of content" to educate Chinese readers about the U.S. election system and debunk right-wing conspiracy theories. Not only that, they wrote about how a second Trump term could potentially negatively affect Chinese Americans. Wu, a software engineer who is 50 and lives in the Bay Area, is a prominent volunteer editor. He says that many Asian-Americans are also taking an interesting route to convince their conservative counterparts by publishing a series of profiles of Chinese Americans that are both left and right-wing. He believes that it's more "effective to combat rumors by telling stories of real people and what they have to say about politics." [9]

WeChat Fake News Feature

In 2017, WeChat released a new feature that warns users if a news item circulating on its app is potentially fake or is a rumor. However, the people who deem it to be fake are typically Chinese censors or police. The feature is also gamified by giving users certain perks or points by reading more "rumour-debunking" articles. [10]

White House Response, Potential Ethical Implications

In response to not only the misinformation, but also concerns about censorship and data collection on the app, the former presidential administration introduced an initiative to ban the app. Those opposed to the ban cited First Amendment rights as a reason why the action would be ethically ambiguous.[11] Users of the app describe the reason they are on it as to stay connected with relatives and friends in China, where multiple Western social media outlets are banned. George Shen, a technology executive in the Boston area, argues that the free existence of WeChat is a threat to the First Amendment itself, as the extent of the false information muffles free speech and discourse.[11] The question of whether the existence of echo chambers dug within WeChat spreading misinformation swings more towards a right of free speech or an abuse of it remains central to the debate.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 “WeChatting American Politics: Misinformation, Polarization, and Immigrant Chinese Media” (15 May 2018. Retrieved on 9 March 2021.), [1]

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "The Logic of a US WeChat Ban" (September 2020. Retrieved on 17 March 2021), [2]

- ↑ "It’s crucial to understand how misinformation flows through diaspora communities" (11 December 2020. Retrieved on 17 March 2021), [3]

- ↑ "On Tech: WeChat unites and divides in America" (6 October 2020. Retrieved on 17 March 2021), [4]

- ↑ "Fake News Is Rampant Even Under Tight Chinese Filters; Crackdown on professional media erodes those outlets' role as public watchdogs" (7 December 2016. Retrieved on 17 March 2021), [5]

- ↑ “2016 Post-Election National Asian American Survey” (16 May 2017. Retrieved on 11 March 2021.), [6]

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 “Misinformation Image on WeChat Attempts to Frighten Chinese Americans Out of Voting” (2 November 2020. Retrieved on 9 March 2021.), [7]

- ↑ "Guo Wengui and Steve Bannon Are Flooding the Zone With Hunter Biden Conspiracies". Foreign Policy. (2 November, 2020). Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/11/02/guo-wengui-steve-bannon-hunter-biden-conspiracies-disinformation/

- ↑ "Liberal Chinese Americans Are Fighting Right-Wing WeChat Disinformation". Foreign Policy. (13 November, 2020). Retrieved March 31, 2021 from https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/11/13/liberal-chinese-americans-fighting-right-wing-wechat-disinformation/

- ↑ "WeChat launches new feature to fight fake news ".(2017, June 11). The Indian Express. Retrieved April 1st, 2021 from https://indianexpress.com/article/technology/social/wechat-launches-new-feature-to-fight-fake-news-4698482/

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 “Chinese censorship invades the U.S. via WeChat” (7 January 2021. Retrieved on 10 March 2021.), [8]