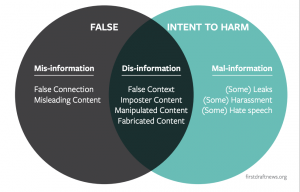

Misinformation

Misinformation is unintentionally inaccurate or misleading information.[2] Examples of misinformation include information that is reported in error, rumors and pranks. Satire and parody as forms of social commentary can result in misinformation if the content is perceived as serious and thus spread as being true.[2] Misinformation is not to be confused with disinformation, which is intentionally inaccurate or misleading information. Both terms, along with “propaganda”, have been studied in association with social media in order to determine their societal impacts, as well as continuous studies on countering misinformation.

Contents

Origins

The invention of the Gutenberg printing press in 1483 acted as an agent of change[4] that escalated the ability for the mass spread of information, misinformation, and disinformation. Information technology is a term that encompasses information distribution technologies such as radio, television, and the Internet.

Examples of False Reports

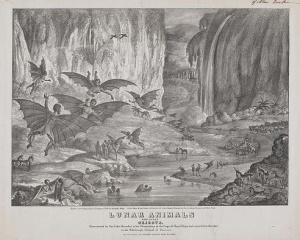

In August of 1885, The New York Sun published a series of 6 articles describing life on the moon. The articles included illustrations of unicorns and flying humans with bat wings. This occurrence became known as “The Great Moon Hoax” of 1835.[5]

In the 1948 election, the Chicago Daily Tribune published an incorrect headline based off of early poll returns that stated: "Dewey Defeats Truman." [6] The headline was later corrected in the evening edition of the Tribune, as Truman had won the 1948 United States presidential election in an upset.[2]

In the 20th century, information technologies became more advanced in comparison to the printing press, featuring the development of television, radio, and the Internet.

In 1983, Mercury Theatre on the Air did a reading of H.G. Wells's story The War of The Worlds on a live radio broadcast. Because they read the story for so long, many listeners tuned in the middle and had no idea a story was being read. The War of The Worlds is a science fiction story about the invasion of England by Martians. Because of the lack of context, listeners began to panic, mistaking the story for a news broadcast. This threw many people into a state of panic. There was even a lawsuit brought against CBS, the station the story had been broadcast on.[8] Orson Wells, the leader of Mercury Theatre on the Air attested in court that their intention was never to frighten people, but just to entertain them. They thought the story was too colorful to ever be believed to be true.

In the 21st century, the Age of Information, these advancements were followed by social media networks. The developments within the Digital Revolution have increased the potential for misinformation to be spread on a massive scale.

Types of Misinformation

Satire or Parody

Satire or parody occurs when a source uses fake information in order to make fun of real news. Without realizing the humor or satire involved, an individual may think the information is true when in fact it is intended to be taken only as a joke. This often occurs on the web where websites can imitate a news source. Two types of satire through news occur: commentary on real news events and wholly fictionalized news stories. The original source of the satire or parody is not considered misinformation, it is when readers believe it to be true and spread the false information without knowing that it is not real.

Imposter Content

Imposter content occurs when a genuine source of information is copied or imitated. Without knowing the distinction between the fake news source and the real source, an individual may receive false content or take content from a source they believed was reliable but was not. A prime example of imposter content would be a Twitter account like "@CNN_News" disseminating content as if it were the actual, legitimate "@CNN" account. A good indicator for determining if a social media news account is legitimate is to check for the verified check from Twitter (or whatever the platform may be, like Instagram or Facebook).

Manipulated Content

Manipulated content occurs when real news or articles are manipulated in order to deceive the reader. Images and videos are easily manipulated through apps like photoshop and therefore manipulated content can be hard to detect when the underlying data is real[9].

Fabricated Content

Fabricated content occurs when fake content is created in order to deceive the reader. Fabricated content often shows up in graphics, images, and videos that are easily sharable. This content easily fills up newsfeeds and readers often fail to check the image's authenticity. This especially becomes a problem when the fabricated content goes viral as people are more likely to share information they find unrealistically entertaining.

False Connection

False connection covers when an article's headings, titles, or images do not accurately represent the content of the article. A common example of false connection is clickbait, which is designed to attract attention to an article or source even though the underlying data might not be related.

Examples of Misinformation

Misinformation in Social Media

The massive spread of misinformation through online social media has been labeled by the World Economic Forum as a global risk.[10] Both social and technical factors have been influential in how social media has become a driver of inaccurate information.[2] According to Caroline Jack, a media historian, computational technologies drive media information in specific directions that circulate across the web regardless of the truth related to the information. [2]

Moreover, a quantitative study conducted on Facebook revealed that "homogeneous and polarized communities (i.e., echo chambers) having similar information consumption patterns" are created when the information presented is related to "distinct narratives" such as conspiracy theories and scientific news.[11] Del Vicario et al. state that it is the homogeneity that serves as the primary driver "for the diffusion of contents".[11]

Facebook's Fight Against Misinformation

The largest problem with countering misinformation in social media is determining what is misinformation. Professor Paul Resnick, associate dean at University of Michigan School of Information, has been conducting research about what constitutes misinformation. He collects many diverse opinions on whether certain things are true, in order to preserve the matter of subjectivity. He has teamed up with Facebook in order to attempt to counter misinformation using this approach. [12] With the aid of Professor Resnick, Facebook is including many people from different backgrounds to help counter misinformation.

See also Parody and Social Networking

Misinformation in news media

Much of the revenue model for news agencies is predicated on releasing information before one's competitors. The reality often leads to content being published with insufficient fact-checking, which consequently can lead to the publishing of misinformation. There may also be bias in the pieces of information that are taken out of context in order to create a headline. Creating a"narrative" has been emphasized as being embedded in what content is deemed important in the news.[1]

Founded in 1988 and based in Chicago, IL, The Onion is a satirical American digital news company. Many of their articles have been mistaken as serious, causing problems since then fake news takes over Facebook feeds.[13]

Outside the United States, Maria Ressa, CEO of Philippine news site Rappler.com and 2018 recipient of Time Magazine’s Person of the Year award for her work as a journalist, has repeatedly reported on the Weaponization of Facebook in the Philippines. Ressa and her team investigated the existence of State-sponsored disinformation campaigns after the 2016 Philippine elections.[14] In an interview with CBS News, Ressa stated: “We always say information is power, right? What happens when information is tainted and toxic sludge poisons are introduced into the body of democracy?"

Misinformation in health

In a study conducted on political rumors encompassing the health care reforms the United States Congress had enacted in 2010, Berinsky stated that risks remain despite source credibility appearing to be an "effective tool for debunking political rumors."[15] Berinsky also writes that "rumors acquire power through familiarity" and attempts to void rumors by directly refuting them as false may actually "facilitate their diffusion by increasing fluency."[15] Misinformation has also caused a reduction in vaccination rates[1] as the idea that vaccinations cause autism is circulating despite no correlation from scientific reasearch. Misinformation in the health care world has also lead to confusion amongst immigrants on what their rights are regarding which obstacles to hospital care are legitimate or not.[16]

Misinformation in politics

A notable instance of misinformation in the political realm is the early 2018 scandal between Cambridge Analytica and Facebook, in which the consulting firm exploited the platform through its acquisition of millions of users’ profile data for political purposes. In relation to this, the United States law enforcement and counterintelligence conducted a two-year long investigation between 2017 and 2019, dubbed the “Special Counsel investigation”, concerning the Russian government’s involvements in the US 2016 Presidential elections. The official report concluded that two main efforts by the Russian government in order to influence the elections were: “disinformation and social media operations” and “computer hacking designed to gather and disseminate information to influence the election.”[17]

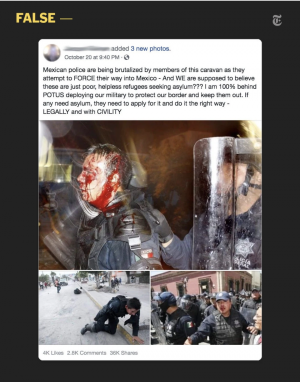

Another prominent controversial political issue, illegal immigration, has allowed for misinformation about the subject to spread. Because both political parties have different stances on the topic, social media users from both political parties have created memes and other media that spreads false information. For example, social media posts showcasing the apparent brutality law enforcement officers were facing in dealing with the large migrant caravans traveling to the southern border from South America. Pictures taken from other circumstances showing bloodied and beaten police officers were used to spread the misinformation that these caravans were inciting violence against the officers at the border in order to come into the country.[18] These accusations were proven false but the post was shared thousands of times leading many to believe this as the truth and thus, realigning their opinions on the matter. In situations like these, it can be nearly impossible to predict and reverse the impact misinformation has on the people it reaches.

See also Fake News

Laws regarding Misinformation

After the Russian media misinformation campaign in the 2016 Presidential Election, Congress introduced the 2017 Honest Ads Act, which would require social media platforms to better manage political advertisements Platforms would have keep copies of political ads, make them public, and release information on who bought the ad space, who they were targeted to, and charge rates. The law would apply to platforms with more than 50 million monthly users, and they would have to disclose information on any party that exceeds $500 in annual political expenditures. This legislation would seek to better regulate the political advertising environment, in order to identify bad actors and their misinformation tactics. [19]

In 2018, California passed S.B. 830, which would requires the state's Department of Education to provide media literacy educational programs and resources. The legislation is based off of a 2016 Stanford University study, which found that 80% of middle school aged children could not decipher between real and fake news stories online. The state will list instructional materials on evaluating online news credibility, create professional development program for state educators, and instruct students on how to properly engage with online news. This law is intended to fight online misinformation activities, not by regulating platforms, but by ensuring youth have the necessary skills and resources to decipher misinformation from real information. [20]

Ethical implications

The dissemination of misinformation, along with disinformation and propaganda, raises various concerns which involves false content or Fake News--especially politically--and in terms of inaccurate health-related information. Researchers have found that accepting new information rather than being skeptical of it is fairly common.[21] The possibility for people to hold misperceptions due to misinformation is significant since if they were to "occur among mass audiences, they may have downstream consequences for health, social harmony, and political life."[22]

The spreading of misinformation can be a dangerous process, and can result in an echo-chamber of fear or toxicity. An occurrence of an incident involving a potential school shooting was taken and perpetuated through false information. On March 16th 2019, tweets circulated that a University of Michigan school building was under threat of a shooter.[23] While this was later found to be an incorrect assessment resulting from a group of students popping balloons which sounded like gun-shots, misinformation spread through Twitter rapidly.

This spread fear throughout the campus and stretched to all corners of the country, and demanded a large team of local policeman to investigate the area. Some students had barricaded themselves in the school library, and students were evacuated floor by floor of the buildings by policemen. The fear and anxiety experienced during the day still lingered even once an all-clear was given, as 19 year old Shivani Bhargava stated in a later remark that she does not "feel safe going to the library anymore."[23]

Other dangerous accounts of misinformation can harm individuals more specifically. People accused of sexual harassment among other crimes, despite a lack of conviction, often have irreparable damage to their reputations, and it can greatly affect their lives in various capacities, most significantly including their likelihood of future employment and their social standing. In the same vein, communities and corporations can also receive irreparable damages to reputation, and there is often no way to recover from these hits. While the quick distribution of information can be helpful rapidly inform individuals on important topics, the same system can be very detrimental in supplanting misinformation in the very same way.

The use of satire, parody, and hoaxing in order to deliver cultural commentary or critique further raises concerns due to the fact that such information could potentially be taken out of context and shared as if it is truth. Jack states that "online content often spreads far beyond its original context" which in turn results in difficulty in determining whether content found online is either "serious or satirical in nature."[2]

Ireton and Posetti describe the negative implications of “poor quality journalism” which may allow misinformation and disinformation “to originate in or leak into the real news system.”[1] They state that the most concerning aspect is the potential impact misinformation has on elections and “the very idea of democracy as a human right” as disinformation “muddies informational waters” and weakens one’s ability to rationalize--especially during election polls.[1] Furthermore, another problem of misinformation is the idea that the “public may come to disbelieve all content--including journalism.”[1]

Researchers Southwell and Thorson have stated that misinformation can be propagated by prominent sources, "especially when such information confirms an audience's pre-existing attitudes."[24] Moreover, as these beliefs become more popular and widespread, it is difficult and time-consuming for the misinformation to be corrected.

Correction of misinformation

Author, director of the American Press Institute, and senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, Tom Resenstiel states: "Misinformation is not like a plumbing problem you fix. It is a social condition, like crime, that you must constantly monitor and adjust to."[25]

Efforts to correct misinformation have been studied in multiple conditions. Southwell and Thorson believe research can aid in determining the most effective ways to correct misinformation.[24] Bode and Vraga also write that while social media is often criticized for the dissemination of misinformation, it can also be utilized as a "corrective to false information."[26]

Bode and Vraga's study using a simulation-based Facebook news feed resulted in their statement that "algorithmic and social corrections are equally effective in limiting misperceptions, and correction occurs for both high and low conspiracy belief individuals."[26] As such, these researchers believe social media campaigns may be utilized in order to "correct global health misinformation."[26]

Lewandowsky and colleagues write that in response to the current "post-truth" world which has "emerged as a result of societal mega-trends," misinformation research must "be considered within a larger political, technological, and societal context." And solutions to misinformation require an interdisciplinary approach between technology and psychology.[27]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Ireton, C., & Posetti, J. (2018). Journalism, ‘Fake News’ & Disinformation. Retrieved from https://en.unesco.org/sites/default/files/journalism_fake_news_disinformation_print_friendly_0.pdf

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Jack, C. (2017). Lexicon of lies: Terms for problematic information. Data & Society, 3. Retrieved from https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2017/08/apo-nid183786-1180516.pdf

- ↑ Day, B. H. (1835). Lunar animals and other objects Discovered by Sir John Herschel in his observatory at the Cape of Good Hope and copied from sketches in the Edinburgh Journal of Science., 1835. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2003665049/.

- ↑ Eisenstein, E. L. (1980). The printing press as an agent of change. Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Thornton, B. (2000). The moon hoax: Debates about ethics in 1835 New York newspapers. Journal of Mass Media Ethics, 15(2), 89-100.

- ↑ Jones, Tim. "Dewey defeats Truman". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved from https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/nationworld/politics/chi-chicagodays-deweydefeats-story-story.html.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ [2]

- ↑ Wardle, Claire. "6 types of misinformation circulated this election season." 18 Nov 2016. Columbia Journalism Review. https://www.cjr.org/tow_center/6_types_election_fake_news.php

- ↑ Howell, L. (2013). Digital wildfires in a hyperconnected world. WEF Report 2013. Available at reports.weforum.org/global-risks-2013/risk-case-1/digital-wildfires-in-ahyperconnected-world.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Del Vicario, M., Bessi, A., Zollo, F., Petroni, F., Scala, A., Caldarelli, G., ... & Quattrociocchi, W. (2016). The spreading of misinformation online. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(3), 554-559. Retrieved from https://www.pnas.org/content/113/3/554.short

- ↑ "Teaming Up Against False News". 10 Apr. 2019. Facebook Newsroom. https://newsroom.fb.com/news/2019/04/inside-feed-misinformation-next-phase/

- ↑ Woolf, N. (2016). As fake news takes over Facebook feeds, many are taking satire as fact, The Guardian. Accessed 28/03/18: https://www.theguardian.com/media/2016/nov/17/facebook-fake-news-satire

- ↑ Ressa, M. (2016). Propaganda war: Weaponizing the internet, Rappler. Retrieved from https://www.rappler.com/nation/148007-propaganda-war-weaponizing-internet

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Berinsky, A. (2017). Rumors and Health Care Reform: Experiments in Political Misinformation. British Journal of Political Science, 47(2), 241-262. doi:10.1017/S0007123415000186

- ↑ " Almeida, L.M., Casanova, C., Caldas, J. et al. J Immigrant Minority Health (2014) 16: 719. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-013-9834-4"

- ↑ "Letter". Retrieved March 24, 2019 – via Scribd.

- ↑ Roose, K. (2018). We Asked for Examples of Election Misinformation. You Delivered. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/04/us/politics/election-misinformation-facebook.html

- ↑ Lecher, Colin. "Senators announce new bill that would regulate online political ads," Verge, 10/19/17, https://www.theverge.com/2017/10/19/16502946/facebook-twitter-russia-honest-ads-act

- ↑ Stowell, Laurie. "California Passes Law to Strengthen Media Literacy in Classrooms," National Council of Teachers of English, 10/24/18, http://www2.ncte.org/report/california-passes-law-strengthen-media-literacy-classrooms/

- ↑ Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U. K. H., Seifert, C. M., Schwarz, N., & Cook, J. (2012). Misinformation and its correction: Continued influence and successful debiasing. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 13(3), 106–131.

- ↑ Southwell, B. G., Thorson, E. A., & Sheble, L. (Eds.). (2018). Misinformation and mass audiences. University of Texas Press.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Berman, M., & Smith, M. (2019). University of Michigan students thought there was an active shooter on campus. It was a false alarm, but the terror was real. Retrieved from https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/nationworld/midwest/ct-false-shooting-alerts-university-michigan-20190319-story.html

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Southwell, B. G., & Thorson, E. A. (2015). The prevalence, consequence, and remedy of misinformation in mass media systems. Retrieved from https://academic.oup.com/joc/article/65/4/589/4082304

- ↑ Anderson, J., & Rainie, L. (2017). The future of truth and misinformation Online. Access: http://www.pewinternet.org/2017/10/19/the-future-of-truth-and-misinformation-online.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Bode, L., & Vraga, E. K. (2018). See something, say something: correction of global health misinformation on social media. Health Communication, 33(9), 1131-1140.

- ↑ Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U. K., & Cook, J. (2017). Beyond misinformation: Understanding and coping with the “post-truth” era. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 6(4), 353-369.