Misinformation

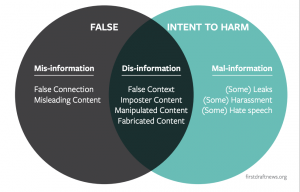

Misinformation is unintentionally inaccurate or misleading information.[2] Information that is reported in error, rumors, and pranks are all examples of misinformation. Satire and parody as forms of social commentary can result in misinformation if the content is considered to be serious and thus spread with the belief that the information is true.[2] Misinformation is not to be confused with disinformation, which is intentionally inaccurate or misleading information. The terms “misinformation” and “disinformation” differ in regards to the intent behind the information diffusion. Both terms, along with “propaganda”, have been studied in association with social media in order to determine their societal impacts, as well as for misinformation correction efforts.

Contents

Origins

The earliest known uses of misinformation, disinformation, and propaganda have been dated back to ancient Rome.[3] These overlapping terms and their history are related to that of mass communication and information technology (IT), which is a term that also encompasses information distribution technologies such as the television.

The invention of the Gutenberg printing press in 1483 acted as an agent of change[5] that escalated the ability for the mass spread of information, misinformation, and disinformation.

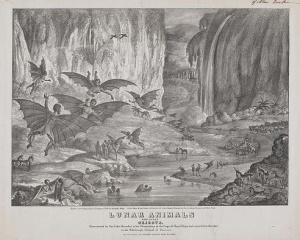

A noteworthy instance of the dissemination of misinformation occurred in August of 1885, in which The New York Sun published a series of 6 articles describing life on the moon. The articles included illustrations of unicorns and flying humans with bat wings. This occurrence became known as “The Great Moon Hoax” of 1835.[6]

In an instance of news reported in error as misinformation, the Chicago Daily Tribune published an incorrect headline based off of early poll returns that stated: "Dewey Defeats Truman." [7] The headline was corrected in the evening edition of the Tribune, as Truman had won the 1948 United States presidential elections in an upset.[2]

In the 20th century, information technologies had become more advanced in comparison to the printing press, featuring the development of television, radio, and the Internet. And in the 21st century, in the Age of Information, these advancements were followed by social media networks. The developments within the Digital Revolution have increased the potential for misinformation to be spread on a massive scale.

Examples of Misinformation

Social media and misinformation

The massive spread of misinformation through online social media has been labeled by the World Economic Forum as a global risk.[8] Both social and technical factors have been influential in how social media has become a driver of inaccurate information.[2] Caroline Jack, a media historian, has written that “computational systems can incentivize or automate media content in ways that result in broader circulation regardless of accuracy or intent.”[2]

Moreover, a quantitative study conducted on Facebook revealed that "homogeneous and polarized communities (i.e., echo chambers) having similar information consumption patterns" are created when the information presented is related to "distinct narratives" such as conspiracy theories and scientific news.[9] Del Vicario et al. state that it is the homogeneity that serves as the primary driver "for the diffusion of contents".[9]

See also Parody.

Misinformation in news media

Much of the revenue model for news agencies is predicated on releasing information before one's competitors. The reality often leads to content being published with insufficient fact checking, which consequently can lead to the publishing of misinformation. There may also be bias in the pieces of information that are taken out of context in order to create a headline--"narrative" has been emphasized as being embedded in what content is deemed important in the news.[1]

Founded in 1988 and based in Chicago, IL, The Onion is a satirical American digital news company. Many of their articles have been mistaken as serious, causing problems as “fake news takes over Facebook feeds.”[10]

Misinformation in health

In a study conducted on political rumors encompassing the health care reforms the United States Congress had enacted in 2010, Berinsky stated that risks remain despite source credibility appearing to be an "effective tool for debunking political rumors."[11] Berinsky also writes that "rumors acquire power through familiarity" and attempts to void rumors by directly refuting them as false may actually "facilitate their diffusion by increasing fluency."[11]

There are also concerns about the reduction of vaccination rates due to misinformation.[1]

Politics and misinformation

A notable instance of misinformation in the political realm is the early 2018 scandal between Cambridge Analytica and Facebook, in which the consulting firm exploited the platform through its acquisition of millions of users’ profile data for political purposes.

In relation to this, the United States law enforcement and counterintelligence conducted a two year long investigation between 2017 and 2019, dubbed the “Special Counsel investigation”, concerning the Russian government’s involvements in the US 2016 Presidential elections. The official report concluded that two main efforts by the Russian government in order to influence the elections were: “disinformation and social media operations” and “computer hacking designed to gather and disseminate information to influence the election.”[12]

See Fake News

Ethical implications

The dissemination of misinformation, along with disinformation and propaganda, raises various concerns which involve false content or Fake News--especially politically--and in terms of inaccurate health-related information. Researchers have described the tendency to accept new information over being skeptical of new information as a fairly common occurrence.[13] The possibility for people to hold misperceptions due to misinformation is significant since if they were to "occur among mass audiences, they may have downstream consequences for health, social harmony, and political life."[14]

The use of satire, parody, and hoaxing in order to deliver cultural commentary or critique further raises concerns due to the fact that such information could potentially be taken out of context and shared as they are considered truthful. Jack states that "online content often spreads far beyond its original context" which in turn results in difficulty in determining whether content found online is either "serious or satirical in nature."[2]

Researchers Southwell and Thorson have stated that misinformation can be propagated by prominent sources, "especially when such information confirms an audience's pre-existing attitudes."[15] Moreover, as these beliefs become more popular and widespread, it is difficult and time-consuming for the misinformation to be corrected.

Correction of misinformation

Author, director of the American Press Institute, and senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, Tom Resenstiel states: "Misinformation is not like a plumbing problem you fix. It is a social condition, like crime, that you must constantly monitor and adjust to."[16]

Efforts to correct misinformation have been studied in multiple conditions. Southwell and Thorson believe research can aid in determining the most effective ways to correct misinformation.[15] Bode and Vraga also write that while social media is often criticized for the dissemination of misinformation, it can also be utilized as a "corrective to false information."[17]

Bode and Vraga's study using a simulation-based Facebook news feed resulted in their statement that "algorithmic and social corrections are equally effective in limiting misperceptions, and correction occurs for both high and low conspiracy belief individuals."[17] As such, these researchers believe social media campaigns may be utilized in order to "correct global health misinformation."[17]

Lewandowsky and colleagues write that in response to the current "post-truth" world which has "emerged as a result of societal mega-trends," misinformation research must "be considered within a larger political, technological, and societal context." And solutions to misinformation require an interdisciplinary approach between technology and psychology.[18]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Ireton, C., & Posetti, J. (2018). Journalism, ‘Fake News’ & Disinformation. Retrieved from https://en.unesco.org/sites/default/files/journalism_fake_news_disinformation_print_friendly_0.pdf

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Jack, C. (2017). Lexicon of lies: Terms for problematic information. Data & Society, 3. Retrieved from https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2017/08/apo-nid183786-1180516.pdf

- ↑ Posetti, J., & Matthews, A. (2018). A short guide to the history of ’fake news’ and disinformation. International Center for Journalists, 20.

- ↑ Day, B. H. (1835). Lunar animals and other objects Discovered by Sir John Herschel in his observatory at the Cape of Good Hope and copied from sketches in the Edinburgh Journal of Science., 1835. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2003665049/.

- ↑ Eisenstein, E. L. (1980). The printing press as an agent of change. Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Thornton, B. (2000). The moon hoax: Debates about ethics in 1835 New York newspapers. Journal of Mass Media Ethics, 15(2), 89-100.

- ↑ Jones, Tim. "Dewey defeats Truman". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved from https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/nationworld/politics/chi-chicagodays-deweydefeats-story-story.html.

- ↑ Howell, L. (2013). Digital wildfires in a hyperconnected world. WEF Report 2013. Available at reports.weforum.org/global-risks-2013/risk-case-1/digital-wildfires-in-ahyperconnected-world.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Del Vicario, M., Bessi, A., Zollo, F., Petroni, F., Scala, A., Caldarelli, G., ... & Quattrociocchi, W. (2016). The spreading of misinformation online. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(3), 554-559. Retrieved from https://www.pnas.org/content/113/3/554.short

- ↑ Woolf, N. (2016). As fake news takes over Facebook feeds, many are taking satire as fact, The Guardian. Accessed 28/03/18: https://www.theguardian.com/media/2016/nov/17/facebook-fake-news-satire

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Berinsky, A. (2017). Rumors and Health Care Reform: Experiments in Political Misinformation. British Journal of Political Science, 47(2), 241-262. doi:10.1017/S0007123415000186

- ↑ "Letter". Retrieved March 24, 2019 – via Scribd.

- ↑ Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U. K. H., Seifert, C. M., Schwarz, N., & Cook, J. (2012). Misinformation and its correction: Continued influence and successful debiasing. Psychological Science in the Public Interest , 13(3), 106–131.

- ↑ Southwell, B. G., Thorson, E. A., & Sheble, L. (Eds.). (2018). Misinformation and mass audiences. University of Texas Press.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Southwell, B. G., & Thorson, E. A. (2015). The prevalence, consequence, and remedy of misinformation in mass media systems. Retrieved from https://academic.oup.com/joc/article/65/4/589/4082304

- ↑ Anderson, J., & Rainie, L. (2017). The future of truth and misinformation Online. Access: http://www.pewinternet.org/2017/10/19/the-future-of-truth-and-misinformation-online.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Bode, L., & Vraga, E. K. (2018). See something, say something: correction of global health misinformation on social media. Health communication, 33(9), 1131-1140.

- ↑ Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U. K., & Cook, J. (2017). Beyond misinformation: Understanding and coping with the “post-truth” era. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 6(4), 353-369.