Difference between revisions of "Misinformation"

| Line 66: | Line 66: | ||

<br /> | <br /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Correction of misinformation== | ||

Revision as of 19:02, 15 March 2019

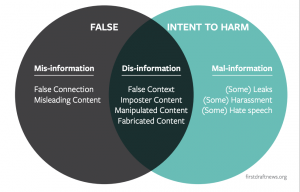

Misinformation is unintentionally inaccurate or misleading information.[2] Information that is reported in error, rumors, and pranks are all examples of misinformation. Satire and parody as forms of social commentary can result in misinformation if the content is considered to be serious and thus spread with the belief that the information is true.[2] Misinformation is not to be confused with disinformation, which is intentionally inaccurate or misleading information. The terms “misinformation” and “disinformation” differ in regards to the intent behind the information diffusion. Both terms, along with “propaganda”, have been studied in association with social media in order to determine their societal impacts, as well as for misinformation correction efforts.

Contents

Origins

The earliest known uses of misinformation, disinformation, and propaganda have been dated back to ancient Rome.[3] These overlapping terms and their history are related to that of mass communication and information technology (IT), which is a term that also encompasses information distribution technologies such as the television.

The invention of the Gutenberg printing press in 1483 acted as an agent of change (insert source) that escalated the ability for the mass spread of information, misinformation, and disinformation.

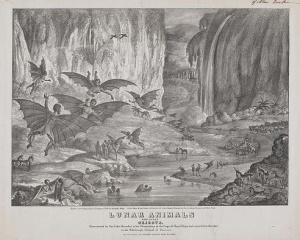

A noteworthy instance of the dissemination of misinformation occurred in August of 1885, in which The New York Sun published a series of 6 articles describing life on the moon. The articles included illustrations of unicorns and flying humans with bat wings. This occurrence became known as “The Great Moon Hoax” of 1835.

In an instance of news reported in error as misinformation, the Chicago Daily Tribune published an incorrect headline based off of early poll returns that stated: "Dewey Defeats Truman." [5] The headline was corrected in the evening edition of the Tribune, as Truman had won the 1948 United States presidential elections in an upset.[2]

In the 20th century, information technologies had become more advanced compared to the printing press, featuring the development of television, radio, and the Internet. And in the 21st century, in the Age of Information, these advancements were followed by social media networks.

Ethical implications

The dissemination of misinformation, along with disinformation and propaganda, raises various concerns which involve false content or Fake News--especially politically--and in terms of inaccurate health-related information. Researchers[6] have described the tendency to accept new information over being skeptical of new information as a fairly common occurrence.

The use of satire, parody, and hoaxing in order to deliver cultural commentary or critique further raises concerns due to the fact that such information could potentially be taken out of context and shared as they are considered truthful. Jack states that "online content often spreads far beyond its original context" which in turn results in difficulty in determining whether content found online is either "serious or satirical in nature."[2]

Researchers Southwell and Thorson have stated that misinformation can be propagated by prominent sources, "especially when such information confirms an audience's pre-existing attitudes."[7] Moreover, as these beliefs become more popular and widespread, it is difficult and time-consuming for the misinformation to be corrected.

Social media and misinformation

The massive spread of misinformation through online social media has been labeled by the World Economic Forum as a global risk.[8]

Both social and technical factors have been influential in how social media has become a driver of inaccurate information.[2]

Caroline Jack, a media historian, wrote that “computational systems can incentivize or automate media content in ways that result in broader circulation regardless of accuracy or intent.”[2]

A quantitative study[9] conducted on Facebook revealed that "homogeneous and polarized communities (i.e., echo chambers) having similar information consumption patterns" are created when the information presented is related to "distinct narratives" such as conspiracy theories and scientific news. Del Vicario et al. state that it is the homogeneity that serves as the primary driver "for the diffusion of contents".[9]

Misinformation in news media

The competition between news sources has led to problems of overlooking fact-checking due to the desire to release a headline before a competitor does so. Jack states that

Misinformation in health

In a study conducted on political rumors encompassing the health care reforms the United States Congress had enacted in 2010, Berinsky stated that risks remain despite source credibility appearing to be an "effective tool for debunking political rumors."[10]

There are also concerns about the reduction of vaccination rates due to misinformation.[1]

Politics and misinformation

Information bias

- Algorithms, filter bubbles, echo chambers

Embedded bias

Correction of misinformation

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Ireton, C., & Posetti, J. (2018). Journalism, ‘Fake News’ & Disinformation. Retrieved from https://en.unesco.org/sites/default/files/journalism_fake_news_disinformation_print_friendly_0.pdf

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Jack, C. (2017). Lexicon of lies: Terms for problematic information. Data & Society, 3. Retrieved from https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2017/08/apo-nid183786-1180516.pdf

- ↑ Posetti, J., & Matthews, A. (2018). A short guide to the history of ’fake news’ and disinformation. International Center for Journalists, https://www. icfj. org/sites/default/files/2018-07/A% 20Short, 20.

- ↑ Day, B. H. (1835). Lunar animals and other objects Discovered by Sir John Herschel in his observatory at the Cape of Good Hope and copied from sketches in the Edinburgh Journal of Science., 1835. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2003665049/.

- ↑ Jones, Tim. "Dewey defeats Truman". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved from https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/nationworld/politics/chi-chicagodays-deweydefeats-story-story.html.

- ↑ Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U. K. H., Seifert, C. M., Schwarz, N., & Cook, J. (2012). Misinformation and its correction: Continued influence and successful debiasing. Psychological Science in the Public Interest , 13(3), 106–131.

- ↑ Southwell, B. G., & Thorson, E. A. (2015). The prevalence, consequence, and remedy of misinformation in mass media systems. Retrieved from https://academic.oup.com/joc/article/65/4/589/4082304

- ↑ Howell, L. (2013). Digital wildfires in a hyperconnected world. WEF Report 2013. Available at reports.weforum.org/global-risks-2013/risk-case-1/digital-wildfires-in-ahyperconnected-world.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Del Vicario, M., Bessi, A., Zollo, F., Petroni, F., Scala, A., Caldarelli, G., ... & Quattrociocchi, W. (2016). The spreading of misinformation online. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(3), 554-559. Retrieved from https://www.pnas.org/content/113/3/554.short

- ↑ Berinsky, A. (2017). Rumors and Health Care Reform: Experiments in Political Misinformation. British Journal of Political Science, 47(2), 241-262. doi:10.1017/S0007123415000186