Difference between revisions of "Misinformation"

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

== Origins == | == Origins == | ||

| − | The earliest known uses of misinformation, disinformation, and propaganda have been dated back to ancient Rome.<ref>Posetti, J., & Matthews, A. (2018). A short guide to the history of ’fake news’ and disinformation. International Center for Journalists, https://www. icfj. org/sites/default/files/2018-07/A% 20Short, 20.</ref> These overlapping terms and their history are related to that of mass communication and information technology (IT), which is a term that also encompasses information distribution technologies such as television. | + | The earliest known uses of misinformation, disinformation, and propaganda have been dated back to ancient Rome.<ref>Posetti, J., & Matthews, A. (2018). A short guide to the history of ’fake news’ and disinformation. International Center for Journalists, https://www. icfj. org/sites/default/files/2018-07/A% 20Short, 20.</ref> These overlapping terms and their history are related to that of mass communication and information technology (IT), which is a term that also encompasses information distribution technologies such as the television. |

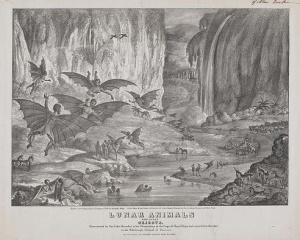

[[File:lunar_animals.jpg|thumbnail|left|Illustration in ''The New York Sun'' depicting supernatural creatures on the Moon as part of The Great Moon Hoax of 1835<ref>Day, B. H. (1835). Lunar animals and other objects Discovered by Sir John Herschel in his observatory at the Cape of Good Hope and copied from sketches in the Edinburgh Journal of Science., 1835. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2003665049/.</ref>]] | [[File:lunar_animals.jpg|thumbnail|left|Illustration in ''The New York Sun'' depicting supernatural creatures on the Moon as part of The Great Moon Hoax of 1835<ref>Day, B. H. (1835). Lunar animals and other objects Discovered by Sir John Herschel in his observatory at the Cape of Good Hope and copied from sketches in the Edinburgh Journal of Science., 1835. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2003665049/.</ref>]] | ||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

A noteworthy instance of the dissemination of misinformation occurred in August of 1885, in which The New York Sun published a series of 6 articles describing life on the moon. The articles included illustrations of unicorns and flying humans with bat wings. This occurrence became known as “The Great Moon Hoax” of 1835. | A noteworthy instance of the dissemination of misinformation occurred in August of 1885, in which The New York Sun published a series of 6 articles describing life on the moon. The articles included illustrations of unicorns and flying humans with bat wings. This occurrence became known as “The Great Moon Hoax” of 1835. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In an instance of news reported in error as misinformation, the Chicago Daily Tribune <ref>Jones, Tim. "Dewey defeats Truman". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved from https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/nationworld/politics/chi-chicagodays-deweydefeats-story-story.html.</ref> | ||

| Line 27: | Line 29: | ||

Social media has been largely attributed to the increased dissemination of misinformation due to both social and technical influences. | Social media has been largely attributed to the increased dissemination of misinformation due to both social and technical influences. | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | <br /> | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

==Ethical implications== | ==Ethical implications== | ||

Revision as of 17:33, 15 March 2019

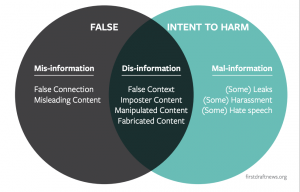

Misinformation is unintentionally inaccurate or misleading information.[1] Information that is reported in error, rumors, and pranks are all examples of misinformation. Satire and parody as forms of social commentary can result in misinformation if the content is considered to be serious and thus spread with the belief that the information is true. Misinformation is not to be confused with disinformation, which is intentionally inaccurate or misleading information. The terms “misinformation” and “disinformation” differ in regards to the intent behind the information diffusion. Both terms, along with “propaganda”, have been studied in association with social media in order to determine their societal impacts, as well as for misinformation correction efforts.

Contents

Origins

The earliest known uses of misinformation, disinformation, and propaganda have been dated back to ancient Rome.[2] These overlapping terms and their history are related to that of mass communication and information technology (IT), which is a term that also encompasses information distribution technologies such as the television.

The invention of the Gutenberg printing press in 1483 acted as an agent of change that escalated the ability for the mass spread of information, misinformation, and disinformation.

A noteworthy instance of the dissemination of misinformation occurred in August of 1885, in which The New York Sun published a series of 6 articles describing life on the moon. The articles included illustrations of unicorns and flying humans with bat wings. This occurrence became known as “The Great Moon Hoax” of 1835.

In an instance of news reported in error as misinformation, the Chicago Daily Tribune [4]

Social media and misinformation

Social media has been largely attributed to the increased dissemination of misinformation due to both social and technical influences.

Ethical implications

The massive spread of misinformation through online social media has been labeled by the World Economic Forum as a global risk.[5] Caroline Jack, a media historian, wrote that “computational systems can incentivize or automate media content in ways that result in broader circulation regardless of accuracy or intent.”[1]

The use of satire, parody, and hoaxing in order to deliver cultural commentary or critique raises concerns due to the fact that such information could potentially be taken out of context and considered truthful. Jack states that "online content often spreads far beyond its original context" which in turn results in difficulty in determining whether content found online is either "serious or satirical in nature."[1]

Misinformation in news media

The competition between news sources has led to problems of overlooking fact-checking due to the desire to a headline before a competitor does so.

Misinformation in health

In a study conducted on political rumors encompassing the health care reforms the United States Congress had enacted in 2010, Berinsky stated that risks remain despite source credibility appearing to be an "effective tool for debunking political rumors."[6]

Embedded bias

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Jack, C. (2017). Lexicon of lies: Terms for problematic information. Data & Society, 3. Retrieved from https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2017/08/apo-nid183786-1180516.pdf

- ↑ Posetti, J., & Matthews, A. (2018). A short guide to the history of ’fake news’ and disinformation. International Center for Journalists, https://www. icfj. org/sites/default/files/2018-07/A% 20Short, 20.

- ↑ Day, B. H. (1835). Lunar animals and other objects Discovered by Sir John Herschel in his observatory at the Cape of Good Hope and copied from sketches in the Edinburgh Journal of Science., 1835. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2003665049/.

- ↑ Jones, Tim. "Dewey defeats Truman". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved from https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/nationworld/politics/chi-chicagodays-deweydefeats-story-story.html.

- ↑ Howell, L. (2013). Digital wildfires in a hyperconnected world. WEF Report 2013. Available at reports.weforum.org/global-risks-2013/risk-case-1/digital-wildfires-in-ahyperconnected-world.

- ↑ Berinsky, A. (2017). Rumors and Health Care Reform: Experiments in Political Misinformation. British Journal of Political Science, 47(2), 241-262. doi:10.1017/S0007123415000186