Difference between revisions of "Metadata"

(→What Metadata Is) |

|||

| Line 36: | Line 36: | ||

**Cached data from websites | **Cached data from websites | ||

**User login details from auto-fill | **User login details from auto-fill | ||

| − | *Digital Photographs | + | *Digital Photographs<ref>“Photo Metadata.” International Press Telecommunications Council, International Press Telecommunications Council, iptc.org/standards/photo-metadata/photo-metadata. Accessed 19 Mar. 2021.</ref> |

**Headline/captions | **Headline/captions | ||

**Owner/rights and licenses | **Owner/rights and licenses | ||

| Line 62: | Line 62: | ||

As for the implications in law, as of 2015 14 bar associations in the United States had made ethics opinions on the use of metadata by lawyers <ref>Perlman, Andrew M. (2010) "The Legal Ethics of Metadata Mining," Akron Law Review: Vol. 43 : Iss. 3 , Article 7. Available at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview/vol43/iss3/7</ref>. These opinions range greatly, with the American bar Association, the Maryland State Bar, and the Vermont State bar outright permitting the use of metadata mining, but the New York State Bar Association Committee on Professional Ethics going as far as to say “lawyers may not ethically use available technology to surreptitiously examine and trace e-mail and other electronic documents.” <ref>Opinion 749. (2020, June 22). Retrieved March 12, 2021, from https://nysba.org/opinion-749/</ref>. | As for the implications in law, as of 2015 14 bar associations in the United States had made ethics opinions on the use of metadata by lawyers <ref>Perlman, Andrew M. (2010) "The Legal Ethics of Metadata Mining," Akron Law Review: Vol. 43 : Iss. 3 , Article 7. Available at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview/vol43/iss3/7</ref>. These opinions range greatly, with the American bar Association, the Maryland State Bar, and the Vermont State bar outright permitting the use of metadata mining, but the New York State Bar Association Committee on Professional Ethics going as far as to say “lawyers may not ethically use available technology to surreptitiously examine and trace e-mail and other electronic documents.” <ref>Opinion 749. (2020, June 22). Retrieved March 12, 2021, from https://nysba.org/opinion-749/</ref>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Photo Metadata=== | ||

| + | Smartphones and digital cameras also embed metadata into the photos that they take. This metadata includes information about the photograph, most notably being the GPS coordinates of where the photo was taken<ref>ABC News. “Image Forensics: What Do Your Photos and Their Metadata Say about You?” ABC News, 23 June 2017, www.abc.net.au/news/2017-06-23/what-your-photos-and-their-metadata-say-about-you/8642630.</ref>. Due to the rise in popularity and quality of smartphone cameras, being able to trace the location of someone's photograph carries problems about individual privacy and tracking. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Instagram and other social media sites have added software that removes the metadata from photos that are uploaded to their sites. This technology works by changing the format of the photo from a .jpeg, or other photo format, into a format designed specifically by the social network. This process compresses the image and scrambles the metadata so it cannot be extracted from the photo once displayed<ref>Random. “Does Instagram Remove EXIF Data from Images?” Alphr, 25 Jan. 2019, www.alphr.com/instagram-remove-exif-data-images.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Digitally altered photos have become popular as means of propaganda during election cycles. Alongside location information, photo metadata also contains information related to their creation, like the time and date, as well as information about the creator. When a photo is altered, this information is written into the edited version. As a result, photo metadata is used to help detect and remove digitally altered photos from news sources in the help to prevent the spread of disinformation<ref>Ellis, Emma Grey. “How to Spot Phony Images and Online Propaganda.” Wired, 17 June 2020, www.wired.com/story/how-to-spot-fake-images.</ref> | ||

==See Also== | ==See Also== | ||

Revision as of 01:25, 19 March 2021

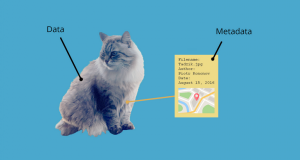

Metadata, specifically the metadata of digital content, can broadly be defined as data about data. More specifically it is the collection of information that helps to summarize the history and current state of various forms of digital information including but not limited to: email, cellular phones, social media accounts/posts, any digital file, and software applications.[1] Metadata is often created as a direct result of viewing and creating other data[2], and is often done so implicitly and without the knowledge of the user. Metadata enables many of the features that users see in the programs, however it potentially comes at the cost of data privacy[1]. New methods of automatically scraping metadata could unknowingly put users' data at risk, and there is still no clear consensus on what to do about it or where the law stands on the issues.[3]

Contents

What Metadata Is

Metadata is data that describes other pieces of data. Historically metadata described the information used in a physical format for the indexing and organization of libraries, but as the use of digital data has continued to rise, the term has been adopted to describe the additional information alongside digital data that fulfills a similar role as the physical counterpart. [4]

Currently, the term can be used to describe a large variety of different types of information, the National Information Standards Organization divides metadata into four categories based on its use: descriptive metadata, structural metadata, administrative metadata, and markup languages. [5]

Descriptive: “For finding or understanding a resource.”

- This includes identifying factors such as the name of the document, the author of it, or related search terms.

Structural: “Relationships of parts of resources to one another”.

- This includes things like page numbers or linking data.

Administrative: A combination of technical information.

- This includes data such as time of creation, creation methods, permissions, and other technical information.

Markup Languages: "Integrates metadata and flags for other structural or semantics features within context."

- This includes information about sections of a piece of data such as lists, paragraphs, etc.

These pieces of information can be very useful for a variety of purposes including resource discovery, organization of resources, interoperability, digital and unique identification, and preservation of data.[5] Therefore the preservation of metadata can be important in the structure of digital databases of all kinds.

Included Information

Due to the large differences in the types of metadata, and data in general, the exact things that different metadata store is largely dependent on what the data it is associated with. Examples of metadata for different types of associated data include:

- Email[1]

- Sender’s name, email, and IP address

- Recipient’s name and email address

- Subject line

- Cellular Phones[1]

- Phone number of every call received

- Time of call

- Duration of call

- Location of caller and recipient

- Web Browsers[1]

- User’s IP address, ISP, device, and OS

- Browser history

- Cached data from websites

- User login details from auto-fill

- Digital Photographs[6]

- Headline/captions

- Owner/rights and licenses

- Capture location

A common theme among the different types of metadata are that they store utility information that can be used by applications to perform further functions. However, metadata also often includes further identifying information than may be obvious to the creator or distributor of the data.[7]

Collection

The collection and viewing of metadata can be done in two main ways, manually and automatically. The manual approach would be the opening of digital files or other data in some form of viewing or editing software and seeking metadata that may be saved along with it. The automatic method, also known as metadata discovery or harvesting, has larger implications due to the volume of data it can process. Companies such as Octopai have begun to use machine learning to manage metadata from within a dataset, and even map out connections and trends in the metadata.[4]

Ethical Implications

Implications in Privacy

One concern about metadata is the threat that it poses to the security of users' information. While the stance on the responsibilities of user privacy when it comes to data in general is more understood and firm, with 120 countries having passed specific laws to protect data privacy as of 2017[8], the situation surrounding metadata is much less clear.

The 2014 Edward Snowden leak revealed the Nation Security Agency in the United States has been deeply involved with the recording and logging of phone calls in foreign countries; however, there is also evidence from the whistleblower Russel Tice that shows that the NSA is collecting the content and metadata of all digital communications.[9] The significance of this massive storing of users’ metadata is that trends and patterns can be used to make assumptions about user activity and identity even without direct evidence of the case.[1]

Additional complications arise when considering encryption the selling of data buy companies. User data, such as email content, is often encrypted so that only the creator and receiver of the data are able to view the content, however metadata is often not encrypted. This gives companies the ability to send the metadata associated with encrypted data, which could be used to come to conclusions that would otherwise be impossible to make. [10]

Implications in Law

A field that is particularly concerned with the ethics of metadata use is the law field in how it relates to discovery and litigation. There has been significant questioning of the ethical implications of accidental discovery of information during legal proceedings due to the improper handling of metadata.[11]There is potential for metadata to unknowingly expose information held under attorney-client privilege, which has led to the use of metadata harvesting utilities being a topic of some debate.[7]

How it is Addressed

There have been a variety of approaches to addressing the ethical issues of metadata both within and across certain fields and applications of metadata. Privacy laws have been enacted to limit the ability of metadata to expose users’ private information, although the breadth of these laws varies greatly by region. The European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation, which went into place in 2018, states that all data that could be used to identity a user must be anonymized, including metadata.[12], where the United States currently is authorized to preform bulk collection of phone metadata under the USA Patriot Act.[13].

As for the implications in law, as of 2015 14 bar associations in the United States had made ethics opinions on the use of metadata by lawyers [14]. These opinions range greatly, with the American bar Association, the Maryland State Bar, and the Vermont State bar outright permitting the use of metadata mining, but the New York State Bar Association Committee on Professional Ethics going as far as to say “lawyers may not ethically use available technology to surreptitiously examine and trace e-mail and other electronic documents.” [15].

Photo Metadata

Smartphones and digital cameras also embed metadata into the photos that they take. This metadata includes information about the photograph, most notably being the GPS coordinates of where the photo was taken[16]. Due to the rise in popularity and quality of smartphone cameras, being able to trace the location of someone's photograph carries problems about individual privacy and tracking.

Instagram and other social media sites have added software that removes the metadata from photos that are uploaded to their sites. This technology works by changing the format of the photo from a .jpeg, or other photo format, into a format designed specifically by the social network. This process compresses the image and scrambles the metadata so it cannot be extracted from the photo once displayed[17]

Digitally altered photos have become popular as means of propaganda during election cycles. Alongside location information, photo metadata also contains information related to their creation, like the time and date, as well as information about the creator. When a photo is altered, this information is written into the edited version. As a result, photo metadata is used to help detect and remove digitally altered photos from news sources in the help to prevent the spread of disinformation[18]

See Also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 "Is metadata collected by the government a threat to your privacy?" TechRepublic. Retrieved March 11, 2021.

- ↑ "Explainer: what is metadata? Should I worry about mandatory data retention?" Guardian. Retrieved March 11, 2021.

- ↑ "The Ethics of Metadata Mining: Ethics Opinion 665 Raises More Questions than Answers"Martindale Legal Library. Retrieved March 11, 2021.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Foote, K. (2021, February 01). A brief history of metadata. Retrieved March 12, 2021, from https://www.dataversity.net/a-brief-history-of-metadata/#

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Riley, J. (2017). Understanding metadata. Washington DC, United States: National Information Standards Organization (http://www.niso.org/publications/press/UnderstandingMetadata.pdf), 23.

- ↑ “Photo Metadata.” International Press Telecommunications Council, International Press Telecommunications Council, iptc.org/standards/photo-metadata/photo-metadata. Accessed 19 Mar. 2021.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Calloway, J. (2009, January 05). Metadata – what is it and what are my ethical duties? Retrieved March 12, 2021, from https://www.llrx.com/2009/01/metadata-what-is-it-and-what-are-my-ethical-duties/

- ↑ Greenleaf, Graham, Global Data Privacy Laws 2017: 120 National Data Privacy Laws, Including Indonesia and Turkey (January 30, 2017). (2017) 145 Privacy Laws & Business International Report, 10-13, UNSW Law Research Paper No. 17-45, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2993035

- ↑ Griffin, T. (2020, December 28). NSA recorded the content of 'every single' call in a foreign country ... and also In America? Retrieved March 12, 2021, from https://washingtonindependent.com/2014/03/nsa-recorded-every-single-call-one-country-country-america/

- ↑ E. (2019, October 28). Your data is shared and sold...what's being done about it? Retrieved March 12, 2021, from https://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article/data-shared-sold-whats-done/

- ↑ Riccardo Tremolada, The Legal Ethics of Metadata: Accidental Discovery of Inadvertently Sent Metadata and the Ethics of Taking Advantage of Others’ Mistakes, 25 RICH. J.L. & TECH., no. 4, 2019.

- ↑ "Complete guide to GDPR compliance" GDPR. Retrieved March 11, 2021.

- ↑ US: End bulk data collection program. (2020, October 28). Retrieved March 12, 2021, from https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/03/05/us-end-bulk-data-collection-program#:~:text=The%20USA%20Freedom%20Act%20prohibits,detail%20records%20(CDR)%20program.

- ↑ Perlman, Andrew M. (2010) "The Legal Ethics of Metadata Mining," Akron Law Review: Vol. 43 : Iss. 3 , Article 7. Available at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview/vol43/iss3/7

- ↑ Opinion 749. (2020, June 22). Retrieved March 12, 2021, from https://nysba.org/opinion-749/

- ↑ ABC News. “Image Forensics: What Do Your Photos and Their Metadata Say about You?” ABC News, 23 June 2017, www.abc.net.au/news/2017-06-23/what-your-photos-and-their-metadata-say-about-you/8642630.

- ↑ Random. “Does Instagram Remove EXIF Data from Images?” Alphr, 25 Jan. 2019, www.alphr.com/instagram-remove-exif-data-images.

- ↑ Ellis, Emma Grey. “How to Spot Phony Images and Online Propaganda.” Wired, 17 June 2020, www.wired.com/story/how-to-spot-fake-images.