Difference between revisions of "Libraries and Ethical Information Technology"

(Added section "Ethical Data Practices for Academic Libraries" + Relevant references) |

(Added Added relevant illustration to "Ethical Data Practices for Academic Libraries" section) |

||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

==Ethical Data Practices for Academic Libraries== | ==Ethical Data Practices for Academic Libraries== | ||

| + | |||

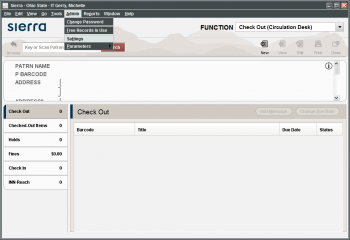

| + | [[File:Library-ethics.jpg|300px|thumbnail|right|Factors affecting personal data practices in libraries<ref>Eroğlu, Personal data perceptions and privacy in Turkish academic libraries: An evaluation for administrations, The Journal of Academic Librarianship, Volume 46, Issue 6, 2020. Accessed: April 6, 2021.</ref>]] | ||

| + | |||

Given the risk associated with both collecting and not collecting library data, libraries are changing their response to the increasing pressures to participate in learning analytics initiatives and the collection and analysis of usage data. Removing identifying information from stored datasets is used as a strategy to mitigate or eliminate risks from unintended disclosure of this type of data<ref>Tene, Omer, and Jules Polonetsky. “Big Data for All: Privacy and User Control in the Age of Analytics.” Nw. J. Tech. & Intell. Prop. 11 (2012): xxvii. Accessed April 6, 2021.</ref>. However, even de identifying a dataset by destroying the links between individually identifying information and other data is possibly insufficient to protect research subjects’ privacy<ref>Khalil, Mohammad, and Martin Ebner. “De-Identification in Learning Analytics.” Journal of Learning Analytics 3, no. 1 (2016): 129–138. Accessed April 6, 2021.</ref>. | Given the risk associated with both collecting and not collecting library data, libraries are changing their response to the increasing pressures to participate in learning analytics initiatives and the collection and analysis of usage data. Removing identifying information from stored datasets is used as a strategy to mitigate or eliminate risks from unintended disclosure of this type of data<ref>Tene, Omer, and Jules Polonetsky. “Big Data for All: Privacy and User Control in the Age of Analytics.” Nw. J. Tech. & Intell. Prop. 11 (2012): xxvii. Accessed April 6, 2021.</ref>. However, even de identifying a dataset by destroying the links between individually identifying information and other data is possibly insufficient to protect research subjects’ privacy<ref>Khalil, Mohammad, and Martin Ebner. “De-Identification in Learning Analytics.” Journal of Learning Analytics 3, no. 1 (2016): 129–138. Accessed April 6, 2021.</ref>. | ||

Revision as of 10:50, 6 April 2021

The study of libraries and ethical information technology refers to the moral relationship between library services and values and information technology methods and developments. The public library as it is known today, concerned with the research, curation, and public dispensation of information, has origins dating back to Roman times.[1][2] In recent years, the world has seen the emergence of Big Data and evolving technology. Some argue that as libraries adapt to these modern information evolutions, they are being increasingly affected by changes in the information landscape.[3] Questions of ethics are being raised as the traditional card catalog system is eschewed in favor of more technology-driven software, such as the Integrated Library System. Additionally, Big Data and the Internet of Things (IOT) are introducing unique questions about patron privacy and information protection in libraries. Lastly, libraries face the ethical implications of information classification and cataloging procedures.

Contents

History

Through information technology advancement, libraries have experienced diverse effects that are increasing dependencies on modern tools. Prior to the 1960s, much of the information handling in libraries was manual, hands-on, and self-contained; however, with the introduction of the Integrated Library System (ILS), this began to change.[4] While ILSes are an organizational construct, they commonly consist of database storage and other software features.[5] For example, a program like Sierra that allows library employees to search for a patron’s account and view all materials they currently have borrowed is a feature of the ILS.[6]

Big Data and Library Ethics

As libraries collect and dispense a wider range of data, there is more discussion about their role and responsibility in relation to Big Data. Academic libraries specifically may be storing information such as full names, social security numbers, and demographics.[4] In software, completely ruling out data leaks is not possible, so inherent risks exist as libraries of any type use these systems and store sensitive information. Library professionals and ethics researchers have begun to question if it is in violation of the aforementioned Code of Ethics to retain these types of sensitive information since data leaks are always a possibility.[4] Additionally, as libraries add resources like e-book mobile applications or special database access to help adapt to changing community needs, they are associating with Big Data companies which some such as Prindle and Loos argue presents ethical challenges because Big Data is, at its core, a profit industry. For example, in 2016, it was discovered that a popular e-book company used by libraries was collecting personal information.[4] These decisions and incidents demonstrate the ethics of how patron information is no longer merely handled by librarians, but also the third-party companies they use. The role of libraries themselves in this new landscape is discussed as well. Bohyun Kim, an associate professor at the University of Rhode Island as well as their Chief Technology Officer, proposes that an ethical challenge of libraries in the information technology age is providing a space for people to reconnect with their values and remember the importance of physical interaction. His belief is that this will inform the ethical use of non-neutral technology.[3]

University of Michigan Library Database

University of Michigan Library services is one that offers a variety of publications to students and faculty for their academic use and research. This service also contains a variety of databases that include scholarly articles, dissertations, and medical publications. Information about campus activities are also readily available. Additional helpful resources would be the feature of “Asking a Librarian”.[8]

Ethical Classification

Libraries also face challenges in ethical classification practices. The Library of Congress Classification (LCC) and the Dewey Decimal Classification (DDC) have both experienced accusations of perpetuating stereotypes or biases. Specifically, the Library of Congress experienced requests for reform over the term “illegal alien” as a search term in the online catalog, and the original version of the Dewey Decimal Classification has been questioned over a large percentage of classification being dedicated to Christianity over other religions.[9] The LCC and DDC are widely used classification systems across the United States. Historically, similar complaints have been made (e.g. cataloging Asians as “Yellow Peril”).[9] Opinions differ on solutions to these ethical dilemmas. Some argue that sustaining a goal of neutrality is unrealistic and even harmful, and some claim that rather than only addressing the problematic classifications themselves, information science should focus on educating librarians to expect and decipher inherently non-neutral information.[9][10]

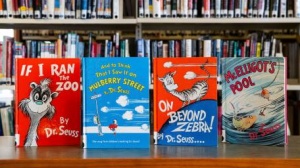

Ethics of Children's Stories

Six Dr. Seuss' books were seized in response to images that may be perceived as racist. [12] Topics arose on how parents could broaden their child’s perspective on issues such as race and discrimination. [13] These books include: “If I Ran the Zoo”, “McElligot’s Pool”, “On Beyond Zebra!”, “Scrambled Eggs Super!”, and “The Cat’s Quizzer”. Libraries face the challenge of whether or not they would like to host “controversial” books such as these in their store. Oftentimes, libraries use the method of “weeding” to control quantity and quality of material brought into the establishment. [14]

Library Initiative OCLC Research

An award granted to OCLC has allowed a diverse group of individuals to come together and improve many different “practices, tools, and workflows in libraries”.[15] This initiative is part of an extensive project. Through this new initiative, OCLC plans to discuss with stakeholders about the systemic biases and racial topics within the current library collection. OCLC also plans to communicate with other libraries that may benefit from gaining additional inclusive collections with their library. [16]

Ethical Data Practices for Academic Libraries

Given the risk associated with both collecting and not collecting library data, libraries are changing their response to the increasing pressures to participate in learning analytics initiatives and the collection and analysis of usage data. Removing identifying information from stored datasets is used as a strategy to mitigate or eliminate risks from unintended disclosure of this type of data[18]. However, even de identifying a dataset by destroying the links between individually identifying information and other data is possibly insufficient to protect research subjects’ privacy[19].

Due to the difficulty of securing “big data” and the legal and ethical risks of disclosure, it should be thought of as a “toxic asset” and treated accordingly. The best way to protect risky data is not to create it. The second best way is to destroy it as soon as possible after analysis is complete. Data destruction plans are therefore an integral component to securely managing privacy and minimizing risks to research subjects. All studies should include a data destruction plan, or a justification of why the data should be retained and for what purpose. Any datasets containing user demographic data or other identifying information should not be retained indefinitely and should be destroyed after a reasonable period following the completion of data analysis[20].

Libraries advocate for their universities to adopt a code of practice for data related to learning analytics. In the absence of an institutional code of practice, libraries develop their own. In this way, libraries have the opportunity to become centers of expertise and best practices for collecting and using institutional data, much as they have in other areas of scholarly communication such as copyright and research data management. Given librarianship’s ethical emphasis on ensuring the privacy of its users, this is a natural—and indeed vital—role for librarians to play as universities continue to develop their learning analytics programs [21].

References

- ↑ Cartwright, Mark. "Libraries in the Ancient World." World History Encyclopedia, 23 July 2019, www.ancient.eu/article/1428/libraries-in-the-ancient-world.

- ↑ Hoq, Kazi M.G. "Information Ethics and Its Implications for Library and Information Professionals: A Contemporary Analysis."Philosophy and Progress, vol. 51, 2014, pp. 37-48, doi.org/10.3329/pp.v51i1-2.17677.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Kim, Bohyun. “Moving Forward with Digital Disruption: What Big Data, IoT, Synthetic Biology, AI, Blockchain, and Platform Businesses Mean to Libraries.” Library Technology Reports, vol. 56, no. 2, 2020, doi:10.5860/ltr.56n2.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Prindle, Sarah and Amber Loos. “Information Ethics and Academic Libraries: Data Privacy in the Era of Big Data.” Journal of Information Ethics, vol. 26, no. 2, Fall 2017, pp. 22-33.

- ↑ "The Integrated Library System (ILS) Primer." Lucidea, www.lucidea.com/special-libraries/the-integrated-library-system-ils-primer.

- ↑ "Sierra." iii, www.iii.com/products/sierra-ils.

- ↑ “Professional Ethics.” American Library Association, www.ala.org/tools/ethics.

- ↑ University of Michigan Library.https://www.lib.umich.edu/

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Noble, Safiya Umoja. Algorithms of Oppression. E-book, New York UP, 2018.

- ↑ Drabinski, Emily. “Teaching the Radical Catalog.” Radical Cataloging: Essays at the Front, edited by K.R. Roberto, McFarland & Co., 2008, pp. 198-205

- ↑ Young, Cathy. "Hypocrisy reigns in Dr. Seuss stir". Newsday. https://www.newsday.com/opinion/columnists/cathy-young/cathy-young-dr-seuss-cancel-culture-books-racism-1.50176800

- ↑ 2021, March 29. “Are Books You Read To Your Children Controversial?”.The Newtown Bee.https://www.newtownbee.com/03292021/are-books-you-read-to-your-children-controversial/

- ↑ 2021, March 29. “Are Books You Read To Your Children Controversial?”.The Newtown Bee.https://www.newtownbee.com/03292021/are-books-you-read-to-your-children-controversial/

- ↑ 2021, March 29. “Are Books You Read To Your Children Controversial?”.The Newtown Bee.https://www.newtownbee.com/03292021/are-books-you-read-to-your-children-controversial/

- ↑ 2021, April 1. “OCLC grant award 'to help improve library practices'”.Research Information.https://www.researchinformation.info/news/oclc-grant-award-help-improve-library-practices

- ↑ 2021, April 1. “OCLC grant award 'to help improve library practices'”.Research Information.https://www.researchinformation.info/news/oclc-grant-award-help-improve-library-practices

- ↑ Eroğlu, Personal data perceptions and privacy in Turkish academic libraries: An evaluation for administrations, The Journal of Academic Librarianship, Volume 46, Issue 6, 2020. Accessed: April 6, 2021.

- ↑ Tene, Omer, and Jules Polonetsky. “Big Data for All: Privacy and User Control in the Age of Analytics.” Nw. J. Tech. & Intell. Prop. 11 (2012): xxvii. Accessed April 6, 2021.

- ↑ Khalil, Mohammad, and Martin Ebner. “De-Identification in Learning Analytics.” Journal of Learning Analytics 3, no. 1 (2016): 129–138. Accessed April 6, 2021.

- ↑ Schneier, Bruce. “Data Is a Toxic Asset - Schneier on Security.” Accessed April 6, 2021. https://www.schneier.com/blog/archives/2016/03/data_is_a_toxic.html.

- ↑ Emmons, Mark, and Frances C. Wilkinson. “The Academic Library Impact on Student Persistence.” College & Research Libraries 72, no. 2 (2011): 128–149. Accessed: April 6,2021.