Difference between revisions of "Informational Friction"

(→Ethical Issues) |

|||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

===Anonymity=== | ===Anonymity=== | ||

| − | In the current informational environment, the use of anonymity in alignment with ICTs may also offer a combination of privacy and informational friction. Beginning with older ICTs and continuing with newer digital ICTs, anonymity contributes to an increase in informational friction, although it is not necessarily comparable to the altogether lack of information friction from ICTs. | + | Kathleen A. Wallace, the professor of Philosophy at Hofstra University defined anonymity as when a given set of traits about a person is not coordinatable to identify the person of interest.<ref>Wallace, Kathleen., 2008. "Online Anonymity". The Handbook of Information and Computer Ethics. pg 168</ref> In the current informational environment, the use of anonymity in alignment with ICTs may also offer a combination of privacy and informational friction. Beginning with older ICTs and continuing with newer digital ICTs, anonymity contributes to an increase in informational friction, although it is not necessarily comparable to the altogether lack of information friction from ICTs. |

==Ethical Issues== | ==Ethical Issues== | ||

Revision as of 17:11, 10 April 2019

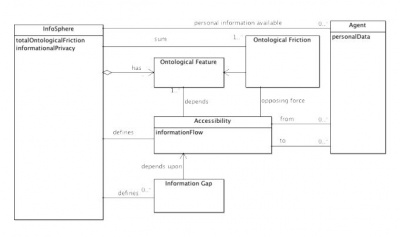

Informational friction, similar to ontological friction[1], is resistance felt in any means for obtainment of information on a

Because informational friction relates to informational privacy, the two may seem conflicting, where achieving a low level of friction and a high level of privacy is impossible. Looking closer at types of data and how they connect to individuals’ privacy may offer some remedy, however, the flux of informational friction continues to complexly relate to progress in informational privacy.

Contents

Friction and ICTs

Information and communication technologies influence the amount of friction in the ongoing transaction of information. The ways in which ICTs can change the flow of information is endless and are often times a hybridization.[4] The ICTs that were catalysts for the digital age tend to only demonstrate an increase in available data and a subsequent decrease in informational friction. Contrarily, many newer ICTs allow for methods to both increase and decrease this friction.[3] Anonymity, although minorly involved with pre-digital technology, has become increasingly significant with recent technology. Its presence plays an important role in both privacy and informational friction. Not only do ICTs set new precedents for available information, decreasing the informational friction, they may also provide settings, including anonymity which can, in turn, increase informational friction.

Pre-Digital ICTs

Pre-digital ICTs tend to offer new affordances that subsequently lessen informational friction.[3] Inventions such as the printing press, telephone, and radio, serve to aid in the progress and sharing of information. These older, pre-digital technologies do not have some of the data control affordances that the digital world utilizes like encryption, authorization, firewalls and more. Because of this, they commonly grapple with a clearer relationship between the amount of collectible data and informational friction.Digital ICTs

As stated before, digital ICTs offer tools for privacy that older ICTs might not. These available options such as encryption, passwords, and enforced privacy policies give some protection to users while simultaneously increasing the informational friction in the digital environment they live. In addition to this, newer ICTs create spaces where sharing and collecting data can be done with great ease and multitude, thus decreasing the informational friction. Digital information and communication technologies hold a complicated relationship with informational friction, offering opportunities to alter it in various ways.Anonymity

Kathleen A. Wallace, the professor of Philosophy at Hofstra University defined anonymity as when a given set of traits about a person is not coordinatable to identify the person of interest.[5] In the current informational environment, the use of anonymity in alignment with ICTs may also offer a combination of privacy and informational friction. Beginning with older ICTs and continuing with newer digital ICTs, anonymity contributes to an increase in informational friction, although it is not necessarily comparable to the altogether lack of information friction from ICTs.

Ethical Issues

Privacy

Ethical issues surrounding privacy, have continued to become more demanding as ICTs affect informational friction. Informational friction often correlates to the level of informational privacy.[1] Individuals or groups who are able to achieve a higher level of privacy by limiting the available knowledge, are increasing the informational friction. The idea of informational friction becomes a middle-man between personal data and the collection of it, where the presence or absence of informational friction is somewhat decisive in user control and privacy. These technologies have continued to decrease informational friction, and thus privacy, yet newer ICTs hold affordances to simultaneously increase friction and privacy. A study conducted in 2011 investigated privacy expectations that personal-data-collecting organizations and groups are presumed to uphold. The findings indicated that both a greater level of familiarity (between the recipient and the individual who's personal data was collected) and a greater level of informational friction yielded a positive influence on the likelihood that the disclosure of the collected information would be in accordance to privacy expectations.[6] The presence of informational friction, however, can often make user interaction with their data more difficult.

Individuals would ideally want the benefits from both having the greatest level of information progress with the lowest amount of informational friction as well as the highest level of informational privacy and protection. These things may work against each other, however, Floridi proposes that if data is separated into “arbitrary” (factual and easily shared information like a name) and “constitutive” (intimate details attributed to a person’s self-identity) the task of offering privacy through protecting users’ identity becomes focused on the latter while continuing to promote the sharing and collection of other information.[3] Other authors on information privacy have proposed similar ideas of focusing on the data that is significant to individuals' self-identity.[7] This information privacy theory is one attempt to increase privacy for the subset of data that is credited to self-identity while decreasing the informational friction for all other data.

Whether we look at types of data differently with weighted priorities for protection or not, there are clear issues surrounding the balance between decreasing the informational friction and maintaining a sense of informational privacy. Ethical concerns enter in deciding where lessening the informational friction will sacrifice privacy and protection or cases of the opposite, where allowing control over personal data creates a large amount of friction in the flow of information.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Floridi, L., Four challenges for a theory of informational privacy, Ethics and Information Technology, 2006, 109–119.

- ↑ Barn, B., An Approach to Early Evaluation of Informational Privacy Requirements, ACM, 2015, 1370-1375.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Floridi, L., The Fourth Revolution: How the Infosphere is Reshaping Human Reality, Privacy, Oxford University Press, 2014, 101-128.

- ↑ Russo, F., Digital Technologies, Ethical Questions, and the Need of an Informational Framework, Philos. Technol., 2018.

- ↑ Wallace, Kathleen., 2008. "Online Anonymity". The Handbook of Information and Computer Ethics. pg 168

- ↑ Martin, K., "TMI (Too Much Information): The Role of Friction and Familiarity in Disclosing Information", 2011, 1-32

- ↑ Shoemaker, D., Self-exposure and exposure of the self: informational privacy and the presentation of identity, 2009.