Human Trafficking

Human Trafficking is the operation of trapping, transporting, and/or transferring people through the use of violence, coercion, and/or manipulation and exploiting them for financial gain [2] [3] [4]. Exploitation can involve forced labor or marriage, domestic servitude, organ extraction, commercial sex acts, and more [5]. As many as 24.9 million adults and children are victims of human trafficking, generating an estimated annual profit of 150 billion US dollars worldwide [6]. High profitability and increased ease in recruiting and advertising victims online have contributed to the growth of human trafficking to the third-largest criminal enterprise globally, with expansion continuing rapidly [7].

Contents

Overview

The number of human trafficking cases has tripled between 2008 and 2019 [8] and has had an estimated 40% rise amid the COVID-19 pandemic. This recent spike is attributed to the slowing of rescue initiatives due to increased travel restrictions and a delayed criminal justice system [9].

Grooming

Human trafficking victims who are minors are often described as being “groomed”. Grooming is a process in which, over time, a predator gains their victim's trust with the intent to exploit them. The intended purpose of grooming is to manipulate victims into becoming willing participants in their abuse. This reduces the likelihood of a victim seeking help and creates a destructive bond to their abuser that may entice them to continue to return to the abuser. There are six stages to grooming: targeting a victim (1), gaining the victim’s trust and information (2), filling a victim’s economic or social need(s) (3), isolate the victim from friends and family (4), abuse begins as a form of “repayment” to the groomer (5), maintain control through violence, fear or blackmail (6) [10].

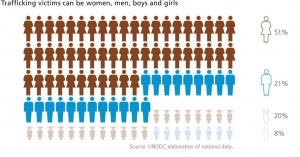

Victim Profile

Human trafficking victims do not fit a single profile. They can be women, men, boys, and girls. Women and girls make up 71% of victims. Females frequently are trafficked for marriage and sexual slavery. Men and boys makeup 21% and 8% respectively of victims and are often used as forced laborers or soldiers. [11]. The most evident commonality between victims is vulnerability. Traffickers exploit psychological, emotional, economic, political, or geographical weaknesses to lure victims. The victims often do not seek help due to fear of traffickers, law enforcement, or even humiliation. In the United States, runaway youth and domestic violence or other trauma victims are particularly vulnerable to trafficking [12].

The Internet's Role In Trafficking

More than half of the global population currently is connected to the internet, totaling over 4.13 billion users [13]. The rise of internet usage worldwide has resulted in the restructuring of many business models to take full advantage of e-commerce and ease of market access. The human trafficking industry is no exception [14].

Recruitment

Social media platforms including, but not limited, to Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, Kik, WhatsApp, and online dating services such as Tinder and Grindr have had instances of recruiting for trafficking reported to The National Human Trafficking Hotline [14].

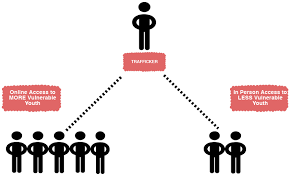

Grooming In the Social Media Age

Social networking sites are used extensively by minors creating an ideal location for finding grooming targets. A 2018 study suggests that 97% of US adolescents aged 13 to 17 use a social media platform such as YouTube, Facebook, Instagram, or Snapchat [16]. Following the previously defined stages of grooming, traffickers may begin by commenting on a post and direct messaging users with extreme flattery and promises of some financial or social gain that they alone can provide. The trafficker will then purchase travel tickets to meet the user face-to-face, where the coercion of money, drugs, shelter, food, or gifts will build the abuser's control over the victim. Offenders may also take a different route and offer a too-good-to-be-true job opportunity that targets migrant laborers or the unemployed [14].

Facebook Lawsuit

In 2018 a human trafficking survivor sued Facebook, alleging that the platform assisted in her recruitment and extortion. The survivor "Jane Doe" was 15 years old when she was recruited on Facebook with promises of a job as a model and later sexually assaulted. Annie McAdams, the attorney for Jane Doe, stated: "It was not just because a pimp did something that Jane Doe was trafficked. That pimp is not able to traffic Jane Doe unless Facebook allowed him to access her [18]." This and two related lawsuits were refuted by Facebook. The Company requested immunity from the claims by appealing to the Communications Decency Act. Facebooks' request was denied under the 2017 Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act, making it illegal for tech companies to knowingly enable sexual exploitation [19]. The cases have since been appealed to the Texas Supreme Court. Oral arguments began on February 21, 2021 [20].

Kik

Kik was a Canada-based free instant messaging service with over 300 million users worldwide. A 2018 BBC investigation found that Kik was involved in over 1,100 UK child sexual abuse cases over five years. Victims described a gradual escalation of photos from selfies to underwear photos and naked photos culminating in videos. One victim said over 100 men contacted them. Kik was often not forthcoming with information to UK law enforcement on potential predators due to US and Canada laws protecting users [21]. The app was criticized heavily for its lack of minor protection measures. In 2019 the app shut down with no reference to these issues. Ted Livingston, Kik's CEO, stated they wanted to focus on the company's cryptocurrency Kin [22].

Advertisement

Advertising victims to find “customers” for their forced service has become far easier with widespread internet access. Large, well-connected, established “brokers” are no longer needed to enter the human trafficking industry. Smaller online brokers are emerging and utilizing the advantages of online anonymity and access to a larger market to find customers [23].

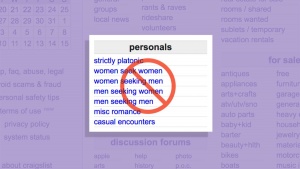

Craigslist

Craigslist is a US classified advertisements website that previously had a section dedicated to “Adult Services” (previously “Erotic Services”) where users could post “adult ads” for sexual services. The company tried initiatives to reduce forced sex postings on the site with charges for posting ads, requiring a phone number to verify the identity of the user, and even hiring attorneys to manually filter ads. After these attempts, the site was still under scrutiny and tried to find more compromises by offering to donate the profit made from this section of the site to the Advocate for Human Rights. However they continued to receive substantial government pressure to shut down the Adult Services section [25]. Craigslist emphasized that their service’s screening process was considerably more robust than other sex-ad companies and if they shut their platform down, buyers and sellers would relocate to these more dangerous outlets [24]. Although the company attempted to work with the government, critics, and law enforcement to create a safe space for sex workers to advertise, they ultimately succumbed to external pressure. The Adult Services section was shut down worldwide in December of 2010. Researcher Mark Latonero cites the Craigslist case as “striking” for the reasons; The lack of empirical research and credible data on the relationship between trafficking and online technologies informing either side of the debate (1), the lack of cooperation between the parties (2), and “a missed opportunity to explore more creative solutions to the problem of trafficking online” [25].

Social Networks

Beyond online sex marketplaces, social networking sites are also frequently used to advertise victims. Nearly 8% of active federal online sex trafficking cases in the US involved advertisements for sex on Facebook in 2017. Traffickers have elaborate methods of posting pictures and hiding location, pricing, and contact information in the caption or comments to obscure the post's true intention from the social media companies. The business pages of Facebook and Yelp contain labor trafficking advertisements [14].

Twitter Lawsuit

A lawsuit was filed against Twitter in California in January 2020. The plaintiff, John Doe, is a minor who had the content of his sexual abuse distributed on Twitter with the platform's knowing refusal to remove the images. Twitter stated that the video, in which sex traffickers pressured John Doe to undress at the age of 13, did not violate any policies. The video accumulated more than 167,000 views before Twitter removed the content after law enforcement got involved. John Doe is suing Twitter for profiting from his sexual exploitation. The Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act and other laws protect the plaintiff from this exploitation [26].

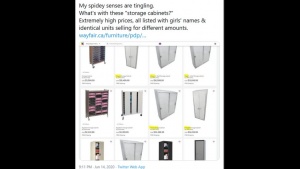

Wayfair Conspiracy

In June 2020, unfounded claims of expensive furniture as a front for child trafficking sold by the American home furnishings company Wayfair became the center of a conspiracy theory that quickly became a global trend. The idea originated from the QAnon far-right conspiracy group that believes there is a deep plot against former President Trump and his most loyal supporters. The original poster came across a page of storage cabinets priced at over $2,000 that were “all listed with girl’s names,” viewers were quick to link some of the girl’s names to actual missing children in the United States. Wayfair responded by attributing their product naming algorithm for the unfortunate choice in names and the high price because the cabinets were industrial grade for commercial use. Other oddly priced items, such as a $10,000 throw pillow, were connected to a price glitch on the website. All affected items were unlisted to create more descriptive names and product information pages [27]. Trafficking hotlines such as the Polaris Project got hundreds of reports relating to this conspiracy. Although the public concern is appreciated, Polaris asked callers to stop Wayfair reports and suggested concerned citizens research “what human trafficking really looks like” [28].

Maintaining Control

Social media has even made it easier for traffickers to maintain control over their victims by impersonating them online, restricting their social media use, and stalking or monitoring their accounts [14].

Anti-Trafficking Initiatives

Corporations

Many corporations have published statements condemning human trafficking and created initiatives to reduce forced labor. Outlined below are the statements and current initiatives of some companies. That being said, there are a few private industries that have taken some initiative to amplify the use of technology to combat human trafficking.

- Google - In December 2011, $11.5 million worth of grants were accumulated to give to anti-trafficking organizations such as Polaris Project, Slavery Footprint, and the International Justice Mission. This allowed for more support for new initiatives using technology [29].

- Microsoft Digital Crimes Unit and Microsoft Research - Collaborated in June 2012 to support human trafficking researchers who developed ideas for research towards the role of technology in commercial sexual exploitation of children. $185,000 was given to six research teams studying technology-facilitated sex trafficking [29].

- Facebook - In their 2020 Anti-Slavery and Human Trafficking Statement condemned human trafficking and committed efforts to keeping forced labor out of their supply chain, including any affiliated businesses. Facebook stated they remove content connected to human trafficking on their networking sites and recommend users report trafficking-related content to local law enforcement and the company. Finally, they committed to raise awareness of human exploitation globally [30].

- Snapchat - Condemned human trafficking and slavery in 2020 statement. "Established a three-pronged approach to evaluate and eradicate risks related to slavery, forced labor, and human trafficking." The parts to this plan include developing supplier policies that require a commitment to not using forced labor, a mandatory training program intended to teach employees to recognize human rights violations, and monitoring and verifying compliance through third-party onsite assessments [31].

- LexisNexis - Introduced many technology-driven tools that help detect, monitor, and research human trafficking. These tools include an online resource center for attorneys, training institute on civil remedies for victims, a national database of social service providers, Human Trafficking Index to track trafficking news [29].

- JP Morgan Chase - Developed tools that apply anti-money laundering arrangements to human-trafficking networks. For example, an investigation on credit card transactions at a nail salon revealed human-trafficking operations [29].

- Palantir Technologies - Worked with the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC) to improve the process of understanding and analyzing the large amounts of human trafficking data from various initiatives [29].

These initiatives often relate to an organization's supply chain and not how users could exploit their product to enable human trafficking. There are many ideas and initiatives at the corporate level to prevent human trafficking through social media networks. Organizations supporting victims have advocated for social media companies to develop these ideas to make social networking safer for all users, especially those who are more vulnerable to falling victim to human trafficking. [14].

Governments

168 countries have criminalized human trafficking but few have addressed the internet's increased role in trafficking [32].

- United States- The most widespread initiative to reduce the internet's increased role in facilitating human trafficking in America came in April 2018. The Allow States and Victims to Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act was passed in the United States. The legislation created state criminal and civil prosecutorial authority against online marketplaces that knowingly participate in sex-trafficking and amended the Mann Act to prohibit using the internet with the intent to promote or facilitate the prostitution of another person [14].

- United Kingdom - Former Home Secretary Sajid Javid was an advocate for holding social media companies accountable for perpetuating online sexual abuse. In 2019 the UK doubled the number of trafficking specialist officers and saw an increase in the number of children safeguarded each month. 500,000 pounds were pledged to educate law enforcement on pinpointing sexual abuse on the internet [33].

- Several countries including the UK and Italy have considered passing new laws that would require an ID card to open social media accounts. The law is intended to reduce posers on the social media accounts and be able to link users to their true identity [34].

References

- ↑ Dunwoody, D. (n.d.). New law seeks to curb human trafficking. Retrieved March 26, 2021, from https://www.wuwf.org/post/new-law-seeks-curb-human-trafficking#stream/0

- ↑ What is human trafficking? (2020, December 18). Retrieved March 12, 2021, from https://www.dhs.gov/blue-campaign/what-human-trafficking

- ↑ What is human trafficking? (2020, December 18). Retrieved March 12, 2021, from https://www.dhs.gov/blue-campaign/what-human-trafficking

- ↑ What is human trafficking? - anti-slavery international. (2020, June 15). Retrieved March 12, 2021, from https://www.antislavery.org/slavery-today/human-trafficking/

- ↑ The Crime. (n.d.). Retrieved March 12, 2021, from https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/human-trafficking/crime.html

- ↑ National slavery and human Trafficking Prevention MONTH, 2020. (2020, January 06). Retrieved March 12, 2021, from https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/01/06/2020-00065/national-slavery-and-human-trafficking-prevention-month-2020

- ↑ Human trafficking: A global enterprise. (2020, July 31). Retrieved March 12, 2021, from https://freeforlifeintl.org/2020/07/31/human-trafficking-a-global-enterprise/

- ↑ Statista Research Department. (2020, November 20). Human Trafficking: Statistics and Facts. Retrieved March 12, 2021, from https://www.statista.com/topics/4238/human-trafficking/#:~:text=Between%202008%20and%202019%20the,greater%20exposure%20of%20the%20issue.

- ↑ Polaris. (2020, April). Crisis In Human Trafficking During The Pandemic. Retrieved March 12, 2021, from https://polarisproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Crisis-in-Human-Trafficking-During-the-Pandemic.pdf

- ↑ Peterson, M. (2019, March 1). 6 stages of grooming in human Trafficking: Fight to End Exploitation. Retrieved March 12, 2021, from https://fighttoendexploitation.org/2019/03/01/grooming-in-human-trafficking/

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Report: Majority of trafficking victims are women and girls; One-third children – United Nations sustainable development. (2016, December 22). Retrieved March 12, 2021, from https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/blog/2016/12/report-majority-of-trafficking-victims-are-women-and-girls-one-third-children/

- ↑ The victims. (2020, April 07). Retrieved March 12, 2021, from https://humantraffickinghotline.org/what-human-trafficking/human-trafficking/victims

- ↑ Clement, J. (2020, October 26). Internet Usage Worldwide: Statistics and Facts. Retrieved March 12, 2021, from https://www.statista.com/topics/1145/internet-usage-worldwide/

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 14.6 Anthony, B. (2018, July). A Roadmap for Systems and Industries to Prevent and Disrupt Human Trafficking: Social Media. Retrieved March 12, 2021, from https://polarisproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/A-Roadmap-for-Systems-and-Industries-to-Prevent-and-Disrupt-Human-Trafficking-Social-Media.pdf

- ↑ Kunz, Ryan etc. Social Media & Sex Trafficking Process. https://www.utoledo.edu/hhs/htsji/pdfs/smr.pdf

- ↑ Mayo Clinic Staff. (2019, December 21). Teens and social media use: What's the impact? Retrieved March 12, 2021, from https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/tween-and-teen-health/in-depth/teens-and-social-media-use/art-20474437#:~:text=Social%20media%20is%20a%20big,%2C%20Facebook%2C%20Instagram%20or%20Snapchat.

- ↑ Jacobs, C. (2020, February 04). Scott County sheriff's Office Warns parents of human trafficking through social media apps. Retrieved March 26, 2021, from https://www.wate.com/news/the-scott-county-sheriffs-office-is-warning-parents-of-human-trafficking-through-social-media-apps/

- ↑ Lozano, J. A. (2018, October 02). Lawsuit accuses Facebook of enabling human traffickers. Retrieved March 26, 2021, from https://apnews.com/article/600b3b75e3954cd9858435c494ccb963

- ↑ Neal, W. (2020, April 29). US court APPROVES SEX-TRAFFICKING lawsuits against facebook. Retrieved March 26, 2021, from https://www.occrp.org/en/daily/12224-us-court-approves-sex-trafficking-lawsuits-against-facebook

- ↑ Cannon, P. (2021, March 13). Texas Supreme court to Hear Facebook human Trafficking Case. Retrieved March 26, 2021, from https://www.simmonsandfletcher.com/blog/texas-supreme-court-facebook-human-trafficking-lawsuit/

- ↑ Crawford, A. (2018, September 21). Kik chat app 'involved in 1,100 child abuse cases'. Retrieved March 26, 2021, from https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-45568276

- ↑ Cerullo, M. (2019, September 24). Kik Chat App, Alleged To Harbor Child Predators, Is Shutting Down. Retrieved March 26, 2021, from https://www.cbsnews.com/news/kik-shutting-down-after-more-than-1000-child-sexual-abuse-cases/

- ↑ Campbell, F. (2016). An analysis of the emerging role of social media in human trafficking. International Journal of Development Issues, 15(2), 98-112. doi:http://dx.doi.org.proxy.lib.umich.edu/10.1108/IJDI-12-2015-0076

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Nedelman, M. (2018, April 11). After Craigslist personals go dark, sex workers fear what's next. Retrieved March 12, 2021, from https://www.cnn.com/2018/04/10/health/sex-workers-craigslist-personals-trafficking-bill

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Latonero, Mark, Human Trafficking Online: The Role of Social Networking Sites and Online Classifieds (September 1, 2011). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2045851 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2045851

- ↑ Statement - twitter sued by survivor of child sexual abuse and exploitation. (2021, February 18). Retrieved March 26, 2021, from https://endsexualexploitation.org/articles/statement-twitter-sued-by-survivor-of-child-sexual-abuse-and-exploitation

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Spring, M. (2020, July 15). Wayfair: The false conspiracy about a furniture firm and child trafficking. Retrieved March 12, 2021, from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-53416247

- ↑ Polaris statement on Wayfair sex Trafficking claims. (2020, July 20). Retrieved March 12, 2021, from https://polarisproject.org/press-releases/polaris-statement-on-wayfair-sex-trafficking-claims/

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 29.4 B. Dixon Jr., Herbert (2013, January). Human Trafficking and the Internet (and Other Technologies Too). Retrieved March 17, 2021, from https://www.americanbar.org/groups/judicial/publications/judges_journal/2013/winter/human_trafficking_and_internet_and_other_technologies_too/

- ↑ Kling, David. Facebook's Anti-Slavery and Human Trafficking Statement. 30 June 2020, s21.q4cdn.com/399680738/files/doc_downloads/2020/06/2020-Facebook's-Anti-Slavery-and-Human-Trafficking-Statement-(FINAL).pdf.

- ↑ Kling, David. Facebook's Anti-Slavery and Human Trafficking Statement. 30 June 2020, s21.q4cdn.com/399680738/files/doc_downloads/2020/06/2020-Facebook's-Anti-Slavery-and-Human-Trafficking-Statement-(FINAL).pdf.

- ↑ US. State Department. (2019, June). 2019 Trafficking in Persons Report. Retrieved March 12, 2021, from https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/2019-Trafficking-in-Persons-Report.pdf

- ↑ Javid, S. (2019, June 25). Tackling child sexual abuse online and offline. Retrieved March 26, 2021, from https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/tackling-child-sexual-abuse-online-and-offline

- ↑ Stone, J. (2019, October 31). New law requiring ID cards to open social media accounts debated in Italy. Retrieved March 26, 2021, from https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/italy-id-cards-social-media-twitter-instagram-facebook-luigi-marattin-a9178976.html