Filter Bubble

Filter Bubbles are pockets of information isolated by algorithms. They occur on websites in which algorithms sort content based on user relevance to present content deemed interesting to the user. They are often criticized for preventing users from being exposed to opposing viewpoints and content that has been deemed irrelevant, and over time transform news feed into a reflection of the user's own ethnocentric ideologies[1]. The term first appeared in Eli Pariser's novel Filter Bubble, which discussed the effects of personalization on the internet as well as the dangers of ideological isolation[2].

Contents

Abstract

The goal of a relevance algorithm is to learn a user's preferences in order to curate content on their feed. This allows a feed to be personalized, being unique depending on the user. Microsoft researcher Tarleton Gillespie explains, "navigate massive databases of information, or the entire web. Recommendation algorithms map our preferences against others, suggesting new or forgotten bits of culture for us to encounter. Algorithms manage our interactions on social networking sites, highlighting the news of one friend while excluding another's. Algorithms designed to calculate what is 'hot' or 'trending' or 'most discussed' skim the cream from the seemingly boundless chatter that's on offer. Together, these algorithms not only help us find information, they provide a means to know what there is to know and how to know it, to participate in social and political discourse, and to familiarize ourselves with the publics in which we participate"[3]. This style of curation fosters user engagement and activism within the site. The concept has a snowballing effect, as more user activism teaches the algorithm to better select content. Soon, the cycle isolates a user. While seeming harmless, when this concept is drawn across political ideologies, it can hinder a person's ability to see alternative points of view. In Stanford University's overview of democracy, a citizen must "listen to the views of other people" and reminds people not to be "so convinced of the rightness of your views that you refuse to see any merit in another position. Consider different interests and points of view"[4]. Thus, to facilitate a constructive democracy, it is important to recognize alternative views.

Social Media as News Media Platforms

In 2016, Pew Research Center collected data on how modern American's use social media. They found 62% of adults turn to social media sites for news information. Of that, 18% do so often, 26% sometimes, and 18% hardly ever [5]. In additional research, Facebook was the most common outlet for Millennials to get news, at 61%, with CNN being second with 44%. Millennials rely on Facebook for political news almost as much as Baby Boomers' rely on local TV for news (60%). For Generation X, the majority, 51%, turn to Facebook for news [6]. Another major influence on political discourse is the extent of political content on Facebook. With 9-in-10 Millenials on Facebook, 77% of Gen Xers, and 57% of Baby Boomers, much of the content they see if political. 24% of Millenials say half or more of their Facebook content is political, while 66% say its more than none, but less than half. For Gen Xer's, 18% say half and 71% less half but more than none of their content is political [7] Facebook also confirmed that their content is 99% authentic and remaining 1% is fake news or clickbaits. [8] Social media algorithms are optimized for engagement and allows users to consume news differently than traditional outlets. They present users with information that is shared by their network and rarely those of opposing viewpoints. This could ultimately isolate people into a stream that confirms their assumptions and suspicions about the world by tailoring people and pages one follows.[9]

Discourse

In a Wired article, Mostafa El-Bermawy shared his findings on the 2016 Presidential Election. Utilizing Google Trends, Google AdWords, and other social media analytic software, El-Bermawy compared numbers between Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton. He found Trump’s social media presence heavily out weighed Clinton’s, averaging more shares on posts and overall followers. The author pointed out the second most popular article shared on social media had earned 1.5 million shares. However, he had never seen or heard of this article. El-Bermawy asked friends around the New York area, only to find the same ignorance. He believes this is the work of filter bubbles, removing a popular article that contested his liberal views [10].

Recent political campaigns have pushed filter bubble's into mainstream discourse. Some argue they are a driving factor behind upset political victories, such as Brexit and Trump's campaign [11]. Social media rely on a relevance based algorithm to sort displayed content[12]. For the first time ever, 62% of American adults receive their news from social media[13]. As media platforms, these sites control the flow of information and political discourse, isolating users in their own cultural or ideological convictions. This became apparent in the Wall Street Journal's article titled "Red Feed, Blue Feed"[14]. The way we consume information has changed. Social media allows us to consume news differently because our news feed is curated and limited by the things that will not make you uncomfortable. Isolating people in their own filter bubbles while creating profound confusion on different political sides. [15] Filter bubbles may also lead to a prevalence of Fake News.

Countering the Filter Bubble

Filter bubbles are caused by people only getting their information from catchy headlines and articles online rather than from engaging in discourse with people from many different backgrounds. In order to reduce the influence of the filter bubble, people can use online media to challenge their biases rather than only find things that confirm them. They can also be cognizant about where they are getting the information from and only get information from reputable places and fact check the information they see using fact-checking websites like Snopes.com.

Ethical Implications

Online Personalization

Most people do not realize that their Google results are personalized to their past searches. Users may start to lose their independence on their social media experience as their identities are structured based on the filter bubbles that they create for themselves by their online searches. In addition to Google, many media outlets and social networks are personalizing content for users based on their searches. This may limit people's exposure to other content as well as their ability to explore new interests. [16] There are many positives and negatives to this personalization, however. For businesses, personalization offers increased relevance for consumers, more clicks on links, and overall increased revenue. [16] Users are benefited because they are more easily able to find content relevant to them. Personalization may be helpful as far as information overload, but it also may not expose users to diverse information, which brings up the issue of what force should determine who sees what and whether that is ethical in the first place. It may also be frustrating for users to see the same content being repeated and raises questions about who has the authority to filter content. [16]

Security

The information that algorithm's collect about users based on what and whom they search and interact with in order to create filter bubbles is not in any way private. Prior searches come up on social media sites as advertisements that anyone could see when the user is browsing their social media. This happens because most website use browser cookies to track their users behavior. A cookie is data sent from a server and stored on the user's computer by the user's browser. The browser then returns the cookie to the server the next time that page is referenced. Most sites require users to enable cookies, thereby propagating filter bubbles. [17]

Information Bias

Many social media algorithms are designed to display the content that users most likely want to see. For example, the Facebook News Feed Algorithm was developed to keep people connected to the people, places, and things they want to be connected to. [18] The News Feed Algorithm decides what content to display based on the people and content that users have previously interacted with. The Facebook algorithm limits the autonomy of the user by deciding what gets displayed on their news feeds for them. The content displayed becomes biased because many people enclose themselves with like minded individuals on their social media networks. When people are only exposed to content that reinforces their previously held beliefs, it becomes difficult for them to accept the legitimacy of opposing beliefs, ultimately enclosing them in their own cultural and ideological bubbles. [19]

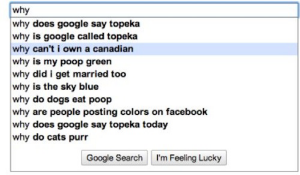

Embedded Bias

While some biases occur as a result of our previous engagement with the technology and it learns to cater to our habits, other biases are built in.This is different than displaying the information that people want to see as per their tastes because these are designed into the platform before it reaches an individual. There has been increased scrutiny on the algorithms of Google, which removed antisemitic and sexist autocomplete phrases after the recent Observer investigation. Additionally, biased rankings in search - either based on what others searched or based on how the algorithm was developed - can shift the opinions of undecided voters. If Google adjusts its algorithm to show more positive search results for certain candidates, the user may form a more positive opinion of that candidate [20]. Similarly, if there is a negative auto-complete option, it will draw between five and 15 times as many clicks as a neutral suggestion. Changing the order of the terms that appear in the auto-complete box has also shown to have an effect on what draws the most clicks and consequently, the information people receive. For example, Google's algorithm does not allow offensive terms in the auto-complete bar. Groups are currently trying to figure out how to get around this algorithm.

See Also

References

- ↑ Staff, NPR. “The Reason Your Feed Became An Echo Chamber - And What To Do About It.” NPR, NPR, 24 July 2016, www.npr.org/sections/alltechconsidered/2016/07/24/486941582/the-reason-your-feed-became-an-echo-chamber-and-what-to-do-about-it.

- ↑ YouTube, PdF. “PdF 2010 | Eli Pariser: Filter Bubble, or How Personalization Is Changing the Web.” YouTube, YouTube, 10 June 2010, www.youtube.com/watch?v=SG4BA7b6ORo.

- ↑ Gillespie, Tarleton. “The Relevance of Algorithms.” Culture Digitally, 26 Nov. 2012, culturedigitally.org/2012/11/the-relevance-of-algorithms/

- ↑ What Is Democracy?, web.stanford.edu/~ldiamond/iraq/WhaIsDemocracy012004.htm

- ↑ Gottfried, Jeffrey, et al. “News Use Across Social Media Platforms 2016.” Pew Research Center's Journalism Project, Pew Research Center's Journalism Project, 27 Dec. 2017, www.journalism.org/2016/05/26/news-use-across-social-media-platforms-2016/.

- ↑ Wormald, Benjamin, and Benjamin Wormald. “Facebook Top Source for Political News Among Millennials.” Pew Research Center's Journalism Project, Pew Research Center's Journalism Project, 1 June 2015, www.journalism.org/2015/06/01/facebook-top-source-for-political-news-among-millennials/.

- ↑ Wormald, Benjamin, and Benjamin Wormald. “Facebook Top Source for Political News Among Millennials.” Pew Research Center's Journalism Project, Pew Research Center's Journalism Project, 1 June 2015, www.journalism.org/2015/06/01/facebook-top-source-for-political-news-among-millennials/.

- ↑ “Mark Zuckerberg.” Mark Zuckerberg - I Want to Share Some Thoughts on..., www.facebook.com/zuck/posts/10103253901916271.

- ↑ Rose-Stockwell, Tobias, and Tobias Rose-Stockwell. “How We Broke Democracy (But Not in the Way You Think).” Medium, Medium, 11 Nov. 2016, medium.com/@tobiasrose/empathy-to-democracy-b7f04ab57eee.

- ↑ El-Bermawy, Mostafa M. “Your Filter Bubble Is Destroying Democracy.” Wired, Conde Nast, 3 June 2017, www.wired.com/2016/11/filter-bubble-destroying-democracy/

- ↑ Jackson, Jasper. “Eli Pariser: Activist Whose Filter Bubble Warnings Presaged Trump and Brexit.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 8 Jan. 2017, www.theguardian.com/media/2017/jan/08/eli-pariser-activist-whose-filter-bubble-warnings-presaged-trump-and-brexit

- ↑ Wang, Chi, et al. “Learning Relevance from Heterogeneous Social Network and Its Application in Online Targeting.” Proceedings of the 34th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information - SIGIR 11, 2011, doi:10.1145/2009916.2010004

- ↑ Gottfried, Jeffrey, et al. “News Use Across Social Media Platforms 2016.” Pew Research Center's Journalism Project, Pew Research Center's Journalism Project, 27 Dec. 2017, www.journalism.org/2016/05/26/news-use-across-social-media-platforms-2016/

- ↑ Keegan, Jon. “Blue Feed, Red Feed.” The Wall Street Journal, Dow Jones & Company, 17 May 2016, graphics.wsj.com/blue-feed-red-feed/

- ↑ Rose-Stockwell, Tobias, and Tobias Rose-Stockwell. “How We Broke Democracy (But Not in the Way You Think).” Medium, Medium, 11 Nov. 2016, medium.com/@tobiasrose/empathy-to-democracy-b7f04ab57eee

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Catone, Josh. "Why Web Personalization May Be Damaging Our World View" Mashable (3 June 2011. Retrieved 22 April 2017).

- ↑ "What Is an Internet Cookie?" HowStuffWorks. N.p., 01 Apr. 2000. Web. 16 Apr. 2017. <http://computer.howstuffworks.com/internet/basics/question82.htm>

- ↑ Backstrom, Lars. "News Feed FYI: Helping Make Sure You Don’t Miss Stories from Friends." Facebook Newsroom. N.p., 29 June 2016. Web. 16 Apr. 2017. <https://newsroom.fb.com/news/2016/06/news-feed-fyi-helping-make-sure-you-dont-miss-stories-from-friends/>.

- ↑ Resnick, Paul. "Bursting Your (Filter) Bubble: Strategies for Promoting Diverse Exposure." CSCW '13: Compilation Publication of CSCW '13 Proceedings & CSCW '13 Companion: February 23-27, 2013, San Antonio TX, USA. By Amy Bruckman and Scott Counts. New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery, 2013. N. pag. Print.

- ↑ Epstein, Robert. “How Google Could Rig the 2016 Election.” POLITICO Magazine, www.politico.com/magazine/story/2015/08/how-google-could-rig-the-2016-election-121548_Page2.html#.WP0m0tLyu01.