Ethics of Blockchain

Blockchain is a distributed database utilizing a distributed ledger. [1] A ledger is a record-keeping system associated with financial accounts. As such, blockchain records transactions in an electronic digital format. A distributed ledger means that there is no central authority like a bank that manages the data. Instead, blockchain is stored on every computer that is running blockchain. Blockchain is secure and, because of no central authority, operates under a decentralized architecture. [1] This makes blockchain an alluring technology to many in the 21st century. However, blockchain also brings about many ethical considerations, including concerns about its high energy usage and privacy concerns.

Contents

History

Blockchain was first introduced in 2008 by someone, or some group, under the name of Satoshi Nakamoto. [2] However, origins of a distributed ledger have surfaced as early as 1982 by a University of California, Berkeley, graduate David Chaum. [3] In 1982, David Chaum published a paper titled Computer Systems Established, Maintained and Trusted by Mutually Suspicious Groups, and in which he first outlined the idea for blockchain. [4]

In 2008, Satoshi Nakamoto solved something that previously remained a flaw for blockchain technologies, that of double spending. [3] Double spending is when users spend the same digital currency twice, and Satoshi Nakamoto solved this problem through his creation of a secure verification system. [3] This improvement allowed for the adoption of blockchain, and, most notably, Bitcoin, which was the first largely adopted cryptocurrency.

Implementation

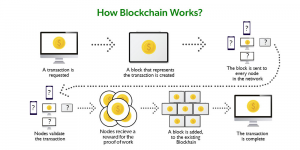

One way in which blockchain is different from a traditional distributed ledger, however, is that information in blockchain is stored in a collection of blocks that, together, form chain(s), hence the name “blockchain”. Blockchain is made up of individual blocks that connect together through cryptographic hashes. [1] Each block connects to a previous block through a cryptographic hash. In aggregate, chains of blocks are formed. Because there is always a way to connect to the previous block in the chain, we can traverse all the way back to the first block ever, known as the “genesis block”. The longest chain in the blockchain is what is collectively agreed upon as the set of information that is legitimate.

Each block stores information such as a sequence ID, a timestamp, a nonce, a cryptographic hash of the previous block, and various metadata fields including some actual transactions such as “Alice sent 1 bitcoin to Bob”.

As mentioned before, what makes blockchain secure is the proof of work mechanism. Since there is no central authority, we need a secure mechanism to verify the legitimacy of any transaction. If anyone were allowed to add blocks to the chain, any user “Tom” could simply just add a block with information such as “Alice sent 100 bitcoins to Tom” and “Bob sent 100 bitcoins to Tom”. Blockchain’s architecture counteracts this by requiring a “proof-of-work” to verify new transactions. [5] Other blockchain users compete against each other to “mine” this new block by guessing random numbers that results in a hash starting with a bunch of 0’s. Because the hashing algorithm is one-way, there is no way to figure out a correct number algorithmically, and it can only be guessed correctly after many many tries. [5] Once someone guesses correctly, other users verify that this block’s transactions are legitimate. This prevents someone from creating fake transactions unless they control the majority of the users of blockchain, which would require billions of dollars.

Applications

Cryptocurrency is perhaps the biggest use case for blockchain. Most cryptocurrencies are implemented with blockchain. Some of the most popular cryptocurrencies used today include Bitcoin (BTC), created in 2009 by Satoshi Nakamoto with a present-day market cap of $440.5 billion, Ethereum (ETH), a present-day market cap of $199 billion, and Tether (USDT), a cryptocurrency that is pegged to the value of $1 USD. [6] As a frame of reference, one Bitcoin costs about $23,095 today. [6]

There are many other use cases of blockchain, but all of them revolve around the idea of decentralization and taking away the dominant control of a single entity and spreading it among the masses. A few examples to note include decentralized VPNs, Web3.0, and healthcare. [7]

Decentralized VPNs

A normal virtual private network (VPN), allows users of the VPN additional privacy and security by encrypting communications and sending them through a secure tunnel managed by a VPN service provider. [8] However, there is still someone managing the secure tunnel and maintaining central control over it. However, with decentralized VPNs, there is no entity that maintains centralized control. Instead, the secure tunnel is created by a set of users who offer their unused network traffic. [8] In this way, people who use decentralized VPNs are both users as well as service providers. They can both use network traffic offered by others and become a node in this network that allows others to use. [8]

Web3.0

The first web pages were static web pages. [9] Then came dynamic web pages with Web2.0. Prior to Web3.0, however, data ownership was always in the hands of big tech companies. [9] Web3.0 seeks to decentralize control of the internet, and enhance the privacy, transparency, and ownership of individual users. [9]

Other applications

Other applications of blockchain include voting, by eliminating the possibility of voter fraud through secure authentication and complete transparency, and even healthcare, through enabling completely secure medical record-keeping. [10]

Ethical Considerations

There are a number of ethical considerations associated with blockchain. One of the main ethical issues involves the enormous amounts of environmental issues that blockchain, specifically mining, causes. It is estimated that between mid-2021 and 2022, cryptocurrency mining contributed to 27.4 million tons of excess carbon dioxide emissions. [11] To put it into perspective on a smaller scale, a single Bitcoin transaction costs about $176 of power. That’s enough to power an average U.S. household’s electricity usage for 6 weeks. [12]

In the sector of healthcare, blockchain poses ethical questions to be grappled with as well. It is impossible to remove any block on a blockchain. Therefore, once information is added to the blockchain, there is no way to discard it. [13] If we choose to record medical information inside a blockchain, all information added to the blockchain will stay there forever, and there is no way for individuals to request their medical data be deleted. [13]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 SoFi. (2022, November 21). Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT) vs. Blockchain. SoFi. Retrieved January 27, 2023, from https://www.sofi.com/learn/content/dlt-vs-blockchain/

- ↑ History of blockchain. ICAEW. (n.d.). Retrieved January 27, 2023, from https://www.icaew.com/technical/technology/blockchain-and-cryptoassets/blockchain-articles/what-is-blockchain/history

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 A brief history of blockchain technology everyone should read. Kriptomat. (2022, March 17). Retrieved January 27, 2023, from https://kriptomat.io/blockchain/history-of-blockchain/

- ↑ Publications. chaum.com. (2022, November 9). Retrieved January 27, 2023, from https://chaum.com/publications/

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 https://www.forbes.com/advisor/investing/cryptocurrency/proof-of-work/

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Royal, J. (n.d.). 12 most popular types of cryptocurrency. Bankrate. Retrieved January 27, 2023, from https://www.bankrate.com/investing/types-of-cryptocurrency/

- ↑ SoFi. (2022, December 1). 9 blockchain uses and applications in 2022. SoFi. Retrieved January 27, 2023, from https://www.sofi.com/learn/content/blockchain-applications/

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 What are decentralized vpns? possible benefits and risks - atlas VPN. atlasVPN. (n.d.). Retrieved January 27, 2023, from https://atlasvpn.com/blog/what-are-decentralized-vpns-possible-benefits-and-risks

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Ashmore, D. (2023, January 9). A brief history of web 3.0. Forbes. Retrieved January 27, 2023, from https://www.forbes.com/advisor/investing/cryptocurrency/what-is-web-3-0/

- ↑ SoFi. (2022, December 1). 9 blockchain uses and applications in 2022. SoFi. Retrieved January 27, 2023, from https://www.sofi.com/learn/content/blockchain-applications/

- ↑ The environmental impacts of cryptomining. Earthjustice. (2022, September 23). Retrieved January 27, 2023, from https://earthjustice.org/features/cryptocurrency-mining-environmental-impacts#:~:text=Top%2Ddown%20estimates%20of%20the,in%20the%20U.S.%20in%202021

- ↑ Calhoun, G. (2022, October 27). The ethics of crypto: Good intentions and bad actors. Forbes. Retrieved January 27, 2023, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/georgecalhoun/2022/10/11/the-ethics-of-crypto-sorting-out-good-intentions-and-bad-actors/?sh=36e9e7815c49

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Leonid. (2022, April 28). Blockchain in Healthcare: Ethical Considerations. CIFS Health. Retrieved January 27, 2023, from https://cifs.health/backgrounds/blockchain-in-healthcare-ethical-considerations/