Erika Kohl

Contents

Exploration of My Data Identity

My investigation into this topic led...

Most of us have Googled our names out of curiosity. At first glance, it appears as nothing more than links to social media accounts. In my case, links to my social media such as LinkedIn and Instagram, are listed at the top. I rarely post on social media and tend to keep my profiles on private, so I assumed little would be found. As I continue scanning through the search result pages, I come across other content, such as my LinkedIn profile picture, and my grandfather’s obituary, which contained a family photo of us. Other than those two instances, I seemed to be relativity hidden in the eyes of Google. What I didn’t expect to find was the numerous counts of online users with my same name. Facebook lists over twenty other profiles, originating in the U.S. and outside, with the name set as Erika Kohl, none of which are mine. The content posted from these other Erika’s varies greatly: YouTube playlists of German rap music, a published self-help book, newspaper obituaries, keto Pinterest boards, and more.

People-Search Sites

While it is uncanny to see my picture appear on the first page of results on Google Images, I remember that’s only a profile picture from my very public LinkedIn account that I made by choice. But this led me to wonder about the other information that may be out there about me, and how easy would it be to find it. Data brokers are companies that collect information on consumers and sell the data to other companies or individuals. The sources of the data come from public records, commercial sources, online sources, and even through individuals themselves [1]. People-search sites are a type of data broker website that allows anyone with internet access to begin a search on someone with as little as the person’s first and last name.

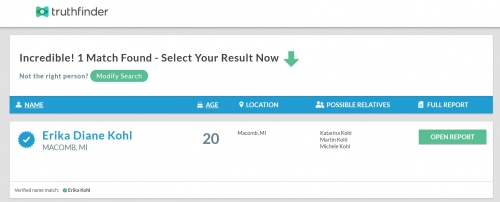

truthfinder

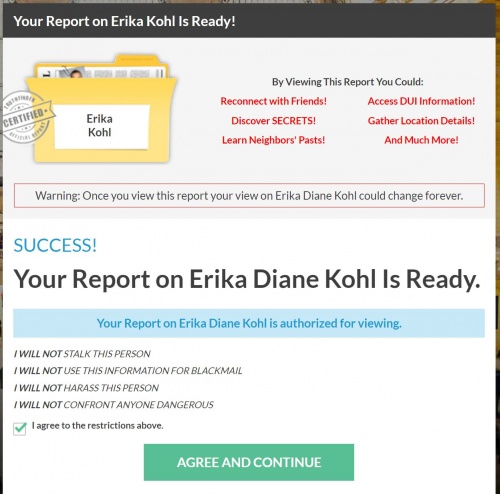

I tried to take my exploration of my online data identity a step further. I searched my name into a person-search website called truthfinder. The results made me feel uneasy. In a matter of seconds, I was surprised with my full name, age, city, and even my mother’s, father’s, and sister’s name. Wanting to know what else this site knew about me; I opened the report. As the site was searching its records and building my profile, it asked, “Do you suspect Erika Kohl to have a criminal record?”. Being fully confident in my answer, I selected “No”. The site then displayed the message, “You may be surprised by Erika’s profile.” … Did I do something illegal that I’m not aware of? The site continued to build up suspense by warning me that I may see “embarrassing or surprising insider information”. What could this site have found that is so embarrassing, it needs a warning? When the report was done being constructed, I was eager to see what the site had uncovered. Unsurprisingly, access to the report was only available with the purchase of a $29.89 monthly subscription.

Whitepages

In order to determine if this information is common throughout other people-search sites, I went to another site, whitepages. Once again, I easily found my name, my age, current city, and my immediate family members’ names. Similarly, access to a full report, which would supposedly include my landline phone number and address, would be available for a fee.

BeenVerified

To see how much more information was available to the public, I searched the phrase, “erika kohl address”. One of the first links on the results pages took me to the website, BeenVerified, with 6 records for persons named “Erika Kohl.” Some of the information listed under my name may be true to another Erika Kohl, but not me. In one report, it stated my age to be 60 years old, and that I was a resident of Texas. In another, it stated my age to be 112 years old and a resident of Maryland. Fortunately, I did not find my address listed.

My Concerns

Accessible vs. Ethical

It appeared that many of the people-search sites I visited marketed themselves as ways of connecting with old classmates, finding lost friends, and discovering family history. However, when the data report is being constructed, the website plays on the user’s emotions. They urgently encourage the user to “seek the truth” about their friends, neighbors, co-workers, and even celebrities. The user is assured that the site holds accurate secrets that the person being searched does not want to be known. Of course, access to the report is blocked and only unlocked with your credit card information.

This raises the question: Is it ethical for these companies to profit off people’s gullibility and desperation to know people’s data? And, if these sites have the information they claim to have, how you can trust that someone will not use it with malicious intent?

As authors Boyd and Crawford put it, “Just because it’s accessible does not make it ethical.” [2] The ability for companies to profit off people’s willingness to pay for “exclusive” information is subject to debate. The data these sites provide could cause serious consequences if fallen into the wrong hands. Companies can legally protect themselves by having users agree to not use the information in certain ways, but it is not guaranteed that their findings won’t be used to cause harm, harassment, online shaming, identify theft, extortion, or vigilante justice purposes.

Another issue lies with the collection of personal data. It is not unreasonable to claim that most people are unaware of how this information ends up on the internet. I know I am. The terms & agreements you agree to when you make an account are obfuscated with legal jargon, giving companies the permission they need to take advantage of your data. Rarely providing a clear way to opt-out of data sharing, the internet is formulated to not put user privacy at the forefront. This, in conjunction with the extensive amount of accounts a single person has on the internet, makes it difficult to know where and how to begin a digital clean of your online data identity. Going through o

Call to Action

Since data broker sites are not considered consumer reporting agencies, they do not have to operate in the same way under the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FRCA)[3]. As of 2014, the Federal Trade Commission has been encouraging Congress to establish laws to educate consumers of the existence and activities of data brokers and grant consumers access to the information about t themselves hold by these corporations. Providing greater transparency and holding data broker companies accountable for their practices is not the final solution, but it’s a start.

Conclusion

The Internet is opening us up to a new and untouched cyberspace in which our limitations to operate in it are not yet set. In my case, the data stored on me isn’t as intrusive as it may be for others. Nonetheless, the results were stable and mostly accurate across the various data broker platforms. Although the information that can be learned from these resources is not representative of my character, the data can still be used with malicious intent. That said, I believe that people-search sites are an irresponsible use of data and further action is needed to protect individuals’ online identities.

References

- ↑ Lomba, D., & Minc, A. (2020, December 11). How to Remove Yourself From Data Broker Sites. Retrieved February 19, 2021, from https://www.minclaw.com/data-broker-websites/

- ↑ Boyd, D., & Crawford, K. (2012) CRITICAL QUESTIONS FOR BIG DATA. Information, Communication & Society, 15:5, 662-679, DOI: 10.1080/1369118X.2012.678878

- ↑ Kagan, J. (2020, September 09). Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA). Retrieved February 19, 2021, from https://www.investopedia.com/terms/f/fair-credit-reporting-act-fcra.asp