Emoji

Emojis are small pictographic images used to represent emotions, symbols, and objects in electronic communication. Emojis were first introduced to ITCs in Japan, where the Japanese words meaning “e” (“picture”) and “moji” (“character”) gave the word its roots. After later being encoded as Unicode characters, emojis have been able to disperse quickly and easily into many different interfaces all across the world. Now there are over 1,400 unique emojis [1] spanning categories including smileys, animals, food, nature, activity, and symbols, and over 6 billion emojis are sent every day[2]. These characters help convey meaning, tone, and creative expression that is often absent in textual conversation. However, the rapid integration of emojis into many different aspects of digital culture gives rise to ethical concerns surrounding literacy and miscommunication, as demonstrated by a few particular court cases.

Contents

History

Emojis were first created by Japanese telecom companies in the early 1990s, during which pagers were a popular form of communication and expression amongst teenagers. NTT Domco was looking for a way to set itself apart from competitors to capitalize in this market. Therefore, inspired by the heart image that NTT Domco already offered in their messaging service, Shigetaka Kurita invented the emoji to offer other visualizations of emotions for use in digital communication[3]. Soon after, many other Japanese mobile companies began to offer similar characters. However, because these emojis were preloaded onto mobile phones, they wouldn't load when sent to other carriers. Therefore, the Unicode Consortium came together in 2005 to encode a standard unicode set of emojis that could be used across carriers [4]. Once adopted by Apple’s iOS5 in 2011, many others including Android, Microsoft, Google, Facebook and Twitter followed suit and have integrated emojis into their program.

Usage & Communication

Since their introduction, emojis quickly emerged into everyday discourse and transformed traditional electronic communication. Emojis are widely used on social media and in digital messaging, with over 74% of Americans and 82% of Chinese saying they have used them in messaging apps[5]. People mostly tend to use emojis that depict facial expressions and body signals, of which the "Face with Tears" emoji ("😂") is the most used, followed by the red heart emoji, and the "Smiling Face with Heart-eyes" emoji ("😍")[6].

When used in communication, emojis enable users to shorten input [6] into messages that would otherwise require more thorough explanation [7], and enhance understanding by offering graphic annotations of visual cues and voice recognition typically present face-to-face and in speech. Beyond strengthening comprehension of one another, emojis also allow for improved cross-cultural communication and understanding as they are a "ubiquitous language"[6] whose illustrations can transcend language barriers [8].

While emojis have fostered understanding amongst individuals and around the world, emojis can also be ambiguous and cause miscommunication. Though they have specific definitions, the interpretation of an emoji's meaning may differ from one person to the next, such as when trying to express humor or sarcasm, and especially when an emoji has double-meaning used to express two different things. For example, the Eggplant emoji ("🍆"), can represent a literal eggplant, but is also commonly used as a sexual innuendo[5], particularly by Americans. Not only are specific emojis used more frequently in certain countries over others, but emojis meaning can differ according to culture.

Culture

Cultural Differences

Usage

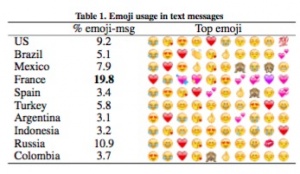

The most frequently used emojis tend to differ from one culture to the next. People in France and Russia have a greater tendency to use emojis related to love. Meanwhile, Australians are more likely to use emojis related to drugs and alcohol [9].

Meaning

The meaning of certain emojis can also often differ from one culture to another. Much of this difference occurs in translation from eastern to western culture. Since emojis originated in Japan, the meaning of an emoji specific to eastern culture may have evolved to imply something else in the West. For example, the "Women with Bunny Ears" emoji ("👯") is often taken to mean fun or "let's party" to the Western world, though it was originally purposed to refer to the equivalent of Playboy Bunnies in Japanese culture [10]. This cultural difference in interpretation extends to other cultures around the world, such as the "Thumbs Up" ("👍") emoji which represents a job-well done in western culture, but implies the Western equivalent of the middle-finger to people in Russia, the Middle East, West Africa, and South America [8].

In Popular Culture

- Oxford Dictionaries named the "Face with Tears of Joy" emoji as the Word of the Year in 2015 [11]

- Emojis have been used in many marketing campaigns such as Coca-Cola [12]

- Facebook used emojis to modify their original "Like" feature to include 6 other types of reactions [13]

- Snapchat incorporated emojis to compare a users friends and show a users achievements in their Trophy Case [14]

Ethics

Emoji usage raises ethical concerns relating to literacy and miscommunication. Emoji's integration into digital communication signifies the shift in traditional methods of reading and writing. Furthermore, emojis imply a change in the human consciousness and how it processes information, as it used to process textual information more literally, but is now able to process information more imaginatively[6] through the open interpretation of the pictorial annotations.

However, this open interpretation of emojis can also lead to miscommunication amongst users who place different meaning on emojis than intended by either the sender or from the actual significance of the emoji. Like text sent from one person to another via an electronic device, the sender's intentions of an emoji can be skewed based on the meaning that is picked up by the receiver. This miscommunication can lead to many consequences, ranging from negligible to catastrophic.

Controversy

In April of 2015, Apple released emoji's in 6 different skin colors. This was in response to user's of darker skin tones feeling unrepresented by the emoticons limited choice.[15] In Apple's release of iOS10 in 2016, Apple changed the pistol emoji to a water gun, put female faces in stereotypical male jobs and sports[16], and similarly added male versions of stereotypically female roles such as that of the dancing women with bunny ears. The iOS 10 update also introduced the rainbow flag which correlated to Apple's public commitment to diversity and the support of causes. [17] Apple's response speaks to the limits of online representation. Through these changes, it shows how much impact societal norms have on a company and the technology involved.

Changing some of the emojis to be more politically accurate has been welcomed by some groups, especially gun control groups regarding the change from gun to water pistol. However, others have mocked it as inconsequential, as it would not reduce crime or solve anything. However, there have been cases where using certain emoji have had real consequences. Along with the gun emoji, several other weapon emojis have been regularly used to threaten people. For example, a 12-year-old girl faced criminal charges for posting the following in an Instagram caption that was interpreted to be threatening her school:[18]

Killing 🔫 “meet me in the library Tuesday” 🔫 🔪 💣

Other cases include a grand jury in New York City that had to decide if 👮🔫🔫🔫 that a teen posted was a real threat to police officers, a Michigan judge who was asked to interpret the meaning of :P, and even a case that reached the Supreme Court over what qualifies as a threat.[18]

Emojis in Court

In a 2015 trial at the Federal District Court in New York City, Ross W. Ulbricht was being charged with managing an online black-market bazaar called Silk Road, where "several thousand vendors sold drugs and other illicit goods." As a federal prosecutor finished reading the text of an internet post, Ulbricht's lawyer raised an objection, saying a smiley face emoji at the end of the post was wrongly omitted from the reading despite being part of the evidence. The lawyer argued that chats were designed to be seen and read, not heard, and that certain forms of writing, such as "???", all capital letters, distorted words like "soooo", and emoticons, couldn't be reliably conveyed orally in court. As a result, he asked all chats involved in the case to be shown to the jury before the trial instead of read out loud.[19]

This case revealed questions about how chats, messages, and symbols should be presented in court, as well as how jurors should be taught about unfamiliar terms like Bitcoin, a virtual currency used to conduct Silk Road transactions, and Tor network, where online activity is anonymous. Lack of understanding about these technical terms and context of emoji-usage raised questions about whether the jury could make the best decisions. This demonstrates that as new technology arises, new rules and regulations also have to evolve to keep up.

(^ Citation from class readings is required here, but I can't remember which reading this idea is from.)

References

- ↑ "Emojipedia.org", Emojipedia. Emoji Statistics. Web. 04 Apr. 2017.

- ↑ Hamilton, Bevan. "Emojis: Are They Changing How We Communicate with Each Other?", CBCnews. CBC/Radio Canada, 04 Apr. 2017.

- ↑ Blagdon, Jeff. "How Emoji Conquered the World.", The Verge. Vox Media, Inc.", 04 Mar. 2013.

- ↑ Y., Y. "What Emoji Are.", The Economist Newspaper. The Economist, 21 July 2015. Web. 04 Apr. 2017.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Sternbergh, Adam. Smile, You're Speaking Emoji: The Rapid Evolution of a Wordless Tongue. 16 Nov. 2014. Web. "Daily Intelligencer. New York Media, LLC"

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Lu, Xuan, Wei Ai, Xuanzhe Liu, Qian Li, Ning Wang, Gang Huang, and Qiaozhu Mei. Learning from the Ubiquitous Language. 12 Sept. 2016. "Proceedings of the 2016 ACM International Joint Conference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing - UbiComp '16 (2016): n. pag. Ubicomp '16."

- ↑ Waude, Adam. Do Emoticons Help Us To Better Communicate Emotions? 29 Apr. 2016. "Psychologist World"

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Danesi, Marcel. The Semiotics of Emoji: The Rise of Visual Language in the Age of the Internet. London: Bloomsbury, 2017. Print

- ↑ Murphy, Samantha. America Leads the World in Cake and Meat Emoji. 22 Apr. 2015. "Mashable"

- ↑ Emojipedia. 👯 Woman With Bunny Ears Emoji. n.d. Web. 04 Apr. 2017. "Emojipedia"

- ↑ Steinmetz, Katy. Oxford's 2015 Word of the Year Is This Emoji. 16 Nov. 2015. "Time Inc"

- ↑ Nudd, Tim. Coke Spreads Happiness Online With Emoji Web Addresses. 19 Feb. 2015. "Adweek"

- ↑ Emojipedia. Facebook. n.d. Web. 04 Apr. 2017. "Emojipedia"

- ↑ Emojipedia. Snapchat. n.d. Web. 04 Apr. 2017. "Emojipedia"

- ↑ Tutt, Paige Apple's New Diverse Emoji n.d. Web. 06 Apr. 2017. "Washington Post"

- ↑ Kelly, Heather Apple replaces the pistol n.d. Web. 06 Apr. 2017. "CNN"

- ↑ http://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/gadgets-and-tech/news/apple-emoji-ios-10-gun-water-pistol-men-women-cats-keyboard-a7167801.html

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Jouvenal, J. (2017). A 12-year-old girl is facing criminal charges for using emoji. She's not alone. The Washington Post. Retrieved 9 April 2017, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/local/wp/2016/02/27/a-12-year-old-girl-is-facing-criminal-charges-for-using-emoji-shes-not-alone/?utm_term=.e1621bcc6b62

- ↑ Weiser, B. (2015). At Silk Road Trial, Lawyers Fight to Include Evidence They Call Vital: Emoji. The New York Times. Retrieved 9 April 2017, from https://www.nytimes.com/2015/01/29/nyregion/trial-silk-road-online-black-market-debating-emojis.html