Difference between revisions of "Depop"

(Created new section titled Re-working plus-sized clothes and added 140 words under it) |

|||

| Line 42: | Line 42: | ||

Reselling thrifted items has been around since the 1990s and was also present on eBay before Depop<ref>Garland B.C., Crawford J.C., Gopalakrishna P. (2015) Second Order Marketing: The Consumer Reseller. In: King R. (eds) Proceedings of the 1991 Academy of Marketing Science (AMS) Annual Conference. Developments in Marketing Science: Proceedings of the Academy of Marketing Science. Springer, Cham. doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-17049-7_12</ref><ref>Murphy, Scott L., and Shuling Liao. "Consumers as Resellers: Exploring the Entrepreneurial Mind of North American Consumers Reselling Online." International Journal of Business and Information, vol. 8, no. 2, 2013, pp. 183-228. ProQuest, https://proxy.lib.umich.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.proxy.lib.umich.edu/scholarly-journals/consumers-as-resellers-exploring-entrepreneurial/docview/1511118119/se-2?accountid=14667.</ref>. In 2004 it was noted that, due to thrift stores' normalization in popular media, middle-income shoppers feel more comfortable buying from such stores. They also use thrift stores to save money and resist a culture of consumption and disposability. Due to thrift stores' growing popularity, there has been an increase in competition from other second-hand stores, discount stores, and online marketplaces. More competition has caused thrift stores to expand their target demographic to more high-income customers, thus the stores move to premier locations, have a clean and inviting interior, and raise prices<ref>Raulli, Julie A. From Shabby to Chic: Upscaling in the United States Thrift Industry, Colorado State University, Ann Arbor, 2005. ProQuest, https://proxy.lib.umich.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.proxy.lib.umich.edu/dissertations-theses/shabby-chic-upscaling-united-states-thrift/docview/305014266/se-2?accountid=14667.</ref>. The specific impact of Depop on this phenomenon is not known. | Reselling thrifted items has been around since the 1990s and was also present on eBay before Depop<ref>Garland B.C., Crawford J.C., Gopalakrishna P. (2015) Second Order Marketing: The Consumer Reseller. In: King R. (eds) Proceedings of the 1991 Academy of Marketing Science (AMS) Annual Conference. Developments in Marketing Science: Proceedings of the Academy of Marketing Science. Springer, Cham. doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-17049-7_12</ref><ref>Murphy, Scott L., and Shuling Liao. "Consumers as Resellers: Exploring the Entrepreneurial Mind of North American Consumers Reselling Online." International Journal of Business and Information, vol. 8, no. 2, 2013, pp. 183-228. ProQuest, https://proxy.lib.umich.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.proxy.lib.umich.edu/scholarly-journals/consumers-as-resellers-exploring-entrepreneurial/docview/1511118119/se-2?accountid=14667.</ref>. In 2004 it was noted that, due to thrift stores' normalization in popular media, middle-income shoppers feel more comfortable buying from such stores. They also use thrift stores to save money and resist a culture of consumption and disposability. Due to thrift stores' growing popularity, there has been an increase in competition from other second-hand stores, discount stores, and online marketplaces. More competition has caused thrift stores to expand their target demographic to more high-income customers, thus the stores move to premier locations, have a clean and inviting interior, and raise prices<ref>Raulli, Julie A. From Shabby to Chic: Upscaling in the United States Thrift Industry, Colorado State University, Ann Arbor, 2005. ProQuest, https://proxy.lib.umich.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.proxy.lib.umich.edu/dissertations-theses/shabby-chic-upscaling-united-states-thrift/docview/305014266/se-2?accountid=14667.</ref>. The specific impact of Depop on this phenomenon is not known. | ||

| − | ===Re-working | + | ===Re-working plus-sized clothes=== |

| − | Selling not just thrifted clothes, but re-worked thrifted clothes have increased in popularity. Newer trends sold and popularized on Depop feature size XL and up shirts turned into sets comprised of multiple clothing items. These can range from crop-top and skirt sets, shorts and shirts with scrunchies sets, or anything that can be created from one large clothing item. These re-worked items are often sold by Depop sellers for more money than the original thrifted item, and they have turned a plus-size item into multiple, small-sized pieces. This makes plus-sized pieces less available in thrift stores and for people of low income. Plus-sizes are often left out of mainstream fashion lines, or if they are included, they can cost more money. People believe that, while re-working a thrifted piece is sustainable, thrifting a plus-size piece and re-working it for a plus-sized person is more ethical. | + | Selling not just thrifted clothes, but re-worked thrifted clothes have increased in popularity. Newer trends sold and popularized on Depop feature size XL and up shirts turned into sets comprised of multiple clothing items. These can range from crop-top and skirt sets, shorts and shirts with scrunchies sets, or anything that can be created from one large clothing item. These re-worked items are often sold by Depop sellers for more money than the original thrifted item, and they have turned a plus-size item into multiple, small-sized pieces. This makes plus-sized pieces less available in thrift stores and for people of low income. Plus-sizes are often left out of mainstream fashion lines, or if they are included, they can cost more money. People believe that, while re-working a thrifted piece is sustainable, thrifting a plus-size piece and re-working it for a plus-sized person is more ethical. |

===Feminization of work=== | ===Feminization of work=== | ||

Revision as of 22:05, 18 March 2021

|

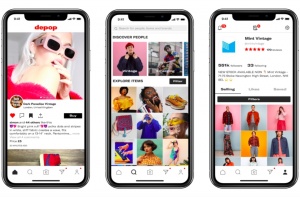

Depop is an online clothing marketplace and social shopping platform that enables users to buy new and used clothing from their internet-enabled devices. It was founded in 2011, and the application was brought to iOS devices in 2013. Depop has many features: users can create a virtual store or profile, follow and interact with other users, buy items, and save items for later, and it is available for both desktop and mobile usage. It also recommends clothing items based on your style[2]. Several ethical issues surrounding how users interact with the platform have arisen.

Contents

History

Simon Beckerman founded Depop in 2011, and the corporate headquarters moved to London in 2012[3][4]. In 2013 the app was later brought to iOS devices. Simon Beckerman then stepped down as CEO and Maria Raga took his place[5][6]. The app was initially developed to sell items from Simon Bekerman’s magazine, PIG, and it was later made available as a website[7][8]. Depop was designed to function as both a social media platform and online marketplace. Beckerman noted Instagram, Twitter, and Pinterest as sources of inspiration[9]. Depop was designed to attract “young designers, cool collectors, small shops and little brands” and its current user base includes younger shoppers and women [10].

Features

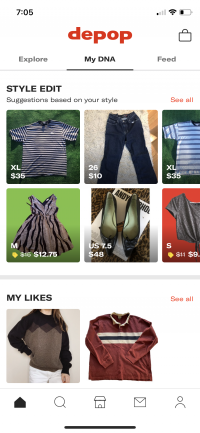

Home page

Depop features a home page. This page consists of several sub-pages, including “Explore,” “My DNA,” and “Feed.” These sub-pages allow you to explore new items, view recommended items, see your saved items, and view the posts of shops you follow[12]. The algorithm that recommends new items is largely based on previous items users have saved and favorited [13].

Selling on Depop

Depop requires you to have an account to buy and sell items. You do not need an account to browse. To sell, you have to set up your shop within the app, and then you can list items. There is an emphasis on entrepreneurship. As Depop founder Simon Beckerman notes, the app is like “having your store in your pocket,” and CEO Maria Raga notes users can “start a business from their bedroom”[14][15].

When listing an item, a maximum of four photos can be posted. Depop suggests users model their items and encourages branding and promoting individual shops on other social media platforms. They support and verify their top sellers, and this often gives them more exposure[16].

Competition

Ethical Issues

Ethical issues have arisen concerning Depop, with some gaining more traction than others. These issues can impact both sellers and buyers.

Reselling thrifted clothing

There has been growing awareness of Depop sellers and their impact on thrift stores, mainly among younger people. Named ‘thrift store gentrification,” this process is mainly critical of thrift stores raising their prices. Recently, online resellers have come under criticism for encouraging this process[17]. This issue is widely debated, and there is not a lot of current research on this topic.

Reselling thrifted items has been around since the 1990s and was also present on eBay before Depop[18][19]. In 2004 it was noted that, due to thrift stores' normalization in popular media, middle-income shoppers feel more comfortable buying from such stores. They also use thrift stores to save money and resist a culture of consumption and disposability. Due to thrift stores' growing popularity, there has been an increase in competition from other second-hand stores, discount stores, and online marketplaces. More competition has caused thrift stores to expand their target demographic to more high-income customers, thus the stores move to premier locations, have a clean and inviting interior, and raise prices[20]. The specific impact of Depop on this phenomenon is not known.

Re-working plus-sized clothes

Selling not just thrifted clothes, but re-worked thrifted clothes have increased in popularity. Newer trends sold and popularized on Depop feature size XL and up shirts turned into sets comprised of multiple clothing items. These can range from crop-top and skirt sets, shorts and shirts with scrunchies sets, or anything that can be created from one large clothing item. These re-worked items are often sold by Depop sellers for more money than the original thrifted item, and they have turned a plus-size item into multiple, small-sized pieces. This makes plus-sized pieces less available in thrift stores and for people of low income. Plus-sizes are often left out of mainstream fashion lines, or if they are included, they can cost more money. People believe that, while re-working a thrifted piece is sustainable, thrifting a plus-size piece and re-working it for a plus-sized person is more ethical.

Feminization of work

Along with other forms of online reselling, Depop faces the issue surrounding its feminization of labor, both as a social media application and a reselling platform. While exact user statistics are not known, Similar apps like Poshmark have noted that registered users tend to be primarily female, with 97% of survey respondents with an account identifying as female[21]. Founder Simon Beckerman notes that “girls who want to sell their whole wardrobe” make up a large part of their customer base, and that “girls love [Depop]."[22]

Women's role in Depop's labor system creates ethical issues. With a focus on creating and maintaining customer relationships and networks, reselling goods online can be incredibly burdening for women. With the reduced ontological friction offered by Depop, sellers often lose their right to ignore information and must be constantly available[24]. Additionally, it is noted that reselling items “is complicated by the emotional labor women must assume in managing their business personae and maintaining flows of communication online."[25]

Depop emphasizes the importance of a professional brand, both on the app and other social media applications[26]. Encouraging a professional brand can be ethically complicated as creating a reselling brand is primarily based on “classed and gendered identities, experiences, networks, and bodies.” [27] The large public social media presence sellers are expected to maintain can lead to additional emotional labor and adverse consequences [28].

Worker's rights

Many sellers on Depop are labeled as bedroom entrepreneurs, however, Depop takes a 10% cut of all sales[29][30]. These sellers do not receive any benefits or job security and can make varying amounts of money. Some more popular shops are known to earn upwards of $150,000 a year. The typical user earns significantly less, often equating to the minimum wage [31]. Depop shares many features and ethical concerns with a gig economy despite labeling its users as entrepreneurs.

Privacy Concerns

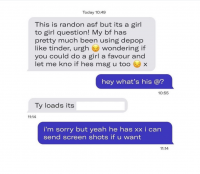

Sexual Harassment

Depop users can face sexual harassment within the internal messaging service. While Depop has a messaging feature, which is used for buyers and sellers to interact, some members utilize it for sexual harassment[32]. One user reported their boyfriend was "pretty much using Depop like Tinder." [33] This can lead to many problems for the young users that are on Depop[34].

Messages illustrating how people use Depop like Tinder [35]

Messages where someone asks someone out over Depop [36]

References

- ↑ Ruback, Brianna. “Depop Raises $62 Million To Fight Counterfeiting, Expand Globally.” Retail TouchPoints, 12 June 2019, https://retailtouchpoints.com/features/financial-news/depop-raises-62-million-to-fight-counterfeiting-expand-globally.

- ↑ Weir, Melanie. “What Is Depop? Here's What You Need to Know about the Clothing Marketplace Platform.” Business Insider, Business Insider, 8 Jan. 2021, https://www.businessinsider.com/what-is-depop.

- ↑ Azeez, Walé. “Depop: We're All Shopkeepers Now.” POLITICO, POLITICO, 12 Nov. 2015, https://www.politico.eu/article/depop-were-all-shopkeepers-now/

- ↑ “Simon Beckerman & Maria Raga.” The Business of Fashion, 1 Oct. 2019, https://www.businessoffashion.com/community/people/maria-raga-simon-beckerman.

- ↑ Pavarini, Maria Cristina. “Stories: Simon Beckerman, Founder/CEO, Depop.com.” The, 13 Jan. 2014, https://www.the-spin-off.com/news/stories/Simon-Beckerman-founderCEO-Depop.com-7789.

- ↑ “Simon Beckerman & Maria Raga.” The Business of Fashion, 1 Oct. 2019, https://www.businessoffashion.com/community/people/maria-raga-simon-beckerman.

- ↑ “About.” Depop, https://www.depop.com/about/.

- ↑ Morrison, Emma. “In Conversation with: Depop Founder Simon Beckerman.” Artefact, 4 June 2015, https://web.archive.org/web/20150716080409/www.artefactmagazine.com/2015/01/14/in-conversation-with-depop-founder-simon-beckerman/.

- ↑ Pavarini, Maria Cristina. “Stories: Simon Beckerman, Founder/CEO, Depop.com.” The, 13 Jan. 2014, https://www.the-spin-off.com/news/stories/Simon-Beckerman-founderCEO-Depop.com-7789.

- ↑ Morrison, Emma. “In Conversation with: Depop Founder Simon Beckerman.” Artefact, 4 June 2015, https://web.archive.org/web/20150716080409/www.artefactmagazine.com/2015/01/14/in-conversation-with-depop-founder-simon-beckerman/.

- ↑ “Depop.” Depop, www.depop.com/.

- ↑ “Depop.” Depop, www.depop.com/.

- ↑ Riley, Jonathon. “Depop For You: A Personal Shopper with Millions of Items to Choose From.” Medium, Engineering at Depop, 15 Oct. 2018, engineering.depop.com/depop-for-you-a-personal-shopper-with-millions-of-items-to-choose-from-6128d231ff23.

- ↑ Morrison, Emma. “In Conversation with: Depop Founder Simon Beckerman.” Artefact, 4 June 2015, https://web.archive.org/web/20150716080409/www.artefactmagazine.com/2015/01/14/in-conversation-with-depop-founder-simon-beckerman/.

- ↑ Lunden, Ingrid. “Depop, a Social App Targeting Millennial and Gen Z Shoppers, Bags $62M, Passes 13M Users.” TechCrunch, TechCrunch, 7 June 2019, https://techcrunch.com/2019/06/06/depop-a-social-app-targeting-millennial-and-gen-z-shoppers-bags-62m-passes-13m-users/.

- ↑ “Seller Handbook.” Depop, https://sellers.depop.com/Seller_Handbook_Final_US.pdf.

- ↑ PheusTheFetus, director. TikTok, 30 Dec. 2020, https://www.tiktok.com/@pheusthefetus/video/6911954574253362438

- ↑ Garland B.C., Crawford J.C., Gopalakrishna P. (2015) Second Order Marketing: The Consumer Reseller. In: King R. (eds) Proceedings of the 1991 Academy of Marketing Science (AMS) Annual Conference. Developments in Marketing Science: Proceedings of the Academy of Marketing Science. Springer, Cham. doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-17049-7_12

- ↑ Murphy, Scott L., and Shuling Liao. "Consumers as Resellers: Exploring the Entrepreneurial Mind of North American Consumers Reselling Online." International Journal of Business and Information, vol. 8, no. 2, 2013, pp. 183-228. ProQuest, https://proxy.lib.umich.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.proxy.lib.umich.edu/scholarly-journals/consumers-as-resellers-exploring-entrepreneurial/docview/1511118119/se-2?accountid=14667.

- ↑ Raulli, Julie A. From Shabby to Chic: Upscaling in the United States Thrift Industry, Colorado State University, Ann Arbor, 2005. ProQuest, https://proxy.lib.umich.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.proxy.lib.umich.edu/dissertations-theses/shabby-chic-upscaling-united-states-thrift/docview/305014266/se-2?accountid=14667.

- ↑ “Poshmark's 2020 Social Commerce Report.” Poshmark, 2020, https://www.report.poshmark.com/#:~:text=Poshmark%20user%20survey%20respondents%20were,community%20of%2060%20million%20users.

- ↑ Morrison, Emma. “In Conversation with: Depop Founder Simon Beckerman.” Artefact, 4 June 2015, https://web.archive.org/web/20150716080409/www.artefactmagazine.com/2015/01/14/in-conversation-with-depop-founder-simon-beckerman/.

- ↑ “Depop.” Depop, www.depop.com/.

- ↑ Floridi, Luciano. “Ethics after the Information Revolution.” The Cambridge Handbook of Information and Computer Ethics, edited by Luciano Floridi, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2010, pp. 3–19.

- ↑ Zhang, Lin. “Fashioning the Feminine Self in ‘Prosumer Capitalism’: Women’s Work and the Transnational Reselling of Western Luxury Online.” Journal of Consumer Culture, vol. 17, no. 2, July 2017, pp. 184–204, doi:10.1177/1469540515572239.

- ↑ “Seller Handbook.” Depop, https://sellers.depop.com/Seller_Handbook_Final_US.pdf.

- ↑ Zhang, Lin. “Fashioning the Feminine Self in ‘Prosumer Capitalism’: Women’s Work and the Transnational Reselling of Western Luxury Online.” Journal of Consumer Culture, vol. 17, no. 2, July 2017, pp. 184–204, doi:10.1177/1469540515572239.

- ↑ Khamis, Susie, et al. “Self-Branding, ‘Micro-Celebrity’ and the Rise of Social Media Influencers.” Celebrity Studies, vol. 8, no. 2, 2016, pp. 191–208., doi:10.1080/19392397.2016.1218292.

- ↑ Lunden, Ingrid. “Depop, a Social App Targeting Millennial and Gen Z Shoppers, Bags $62M, Passes 13M Users.” TechCrunch, TechCrunch, 7 June 2019, https://techcrunch.com/2019/06/06/depop-a-social-app-targeting-millennial-and-gen-z-shoppers-bags-62m-passes-13m-users/.

- ↑ “Seller Handbook.” Depop, https://sellers.depop.com/Seller_Handbook_Final_US.pdf.

- ↑ Butler, Sarah. “'Everyone I Know Buys Vintage': the Depop Sellers Shaking up Fashion.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 20 Oct. 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/business/2018/oct/20/everyone-i-know-buys-vintage-the-depop-sellers-shaking-up-fashion.

- ↑ Lieber, Chavie. “The Dark Side of Depop.” The Business of Fashion, The Business of Fashion, 12 Nov. 2019, https://www.businessoffashion.com/articles/technology/depop-sexual-harassment-internet-safety.

- ↑ https://www.instagram.com/p/CFm4JWfBrNP/

- ↑ Knowles, Kitty. “Depop CEO: Solving 3 Big Problems For Young Cool Shoppers.” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 26 Apr. 2018, https://www.forbes.com/sites/kittyknowles/2018/04/26/depop-ceo-solving-3-big-problems-for-young-cool-shoppers/?sh=7d3a25477b40.

- ↑ https://www.instagram.com/p/CFm4JWfBrNP/

- ↑ https://www.instagram.com/p/CEd4sAVhlrO/