David Song

Contents

To You, After 2000 Years

I was born in the year 2000, the beginning of the new millenium. To conspiracists, it was the year of catastrophic doom. To the Chinese lunar calendar, it was the Year of the Dragon. To me, it was the starting point of my generation, those who grew up encased in digital technology. Unlike some of my peers however, my social media usage is comparatively low. The sole social media account I own and use semi-regularly is Facebook. But in a society where creating and maintaining connections through computers is widespread, what becomes of the disconnected user’s real identity? And conversely, am I now required to have a digital identity? To better understand the implicit demands of digital identities and following consequences of reduced online interaction on reality, I began my search for the selves I’ve spread across the Internet.

search?q=david+song

The first step to finding anyone online is searching their name. It’s how we distinguish ourselves. Growing up as an Asian American from the Midwest, I used to think my name was somewhat unique. For the non-religious, it’s a biblical reference to a Hebrew king famous for defeating Goliath, the classic underdog narrative. It wasn’t until I became more involved in Asian American communities that I realized my name is actually extremely common among Asian Americans. Even while narrowing my scope to the University of Michigan, I am one of five David Songs. With my wistful resignation that I belong to a larger collective, I searched my name with the world’s most used search engine: Google.com. As expected, I observed that my name’s search results were inundated with countless other David Songs, all of whom were far more successful than me. It also became immediately clear that societally-valued aspects of one’s identity like occupation can affect their digital identity’s value. For instance, Google’s searching algorithm prioritized returning LinkedIn pages, which gained noticeably more traffic than other forms of identification. I use LinkedIn sparingly and have a smaller network, so my digital identity is valued less. Twenty pages later, I was still nowhere close to finding a fragment of my online identity. I soon managed to reach the final page of results without finding anything related to me. Instead of showing everyone eventually, visibility is limited to a fixed amount of server space. While the theme of valuing people based on certain qualities is mirrored in normal society, digital identities aren’t guaranteed inherent value just by existing. Even though countless David Songs exist, I’m one of them. According to Google? I’m nobody.

Hansel and Gretel

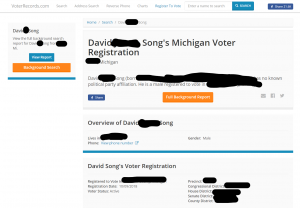

Hypothesizing that specifying my search further could work, I tried rerunning the query again along with my middle name and finally, I obtained results. Using my full legal name returned a mysterious website registered as VoterRecords.com. This particular record of mine had my date of birth, current home address, date of registration, and voter ID number. Of course without my middle name, which I’ve told few, it would be extremely difficult to locate this exact webpage. But learning that someone’s address could be doxxed so easily, especially when the website is known in advance, was a discomforting realization. What concerned me even further was seeing my parents and neighbors’ information being recommended too. By voting and fulfilling my civic duty in America, I had unintentionally created a trail of digital breadcrumbs to my family. Thankfully, VoterRecords offers to remove online records given that one has the legal right which I promptly exercised. I initially assumed that my digital identity was near nonexistent due to minimal social media interaction, yet my encounter with VoterRecords demonstrated the complete opposite. Real-world actions have a say in shaping your digital identity, either with or without your informed consent.

Anti Anti Social Media

It’s no secret that digital identities aren’t an authentic depiction of ourselves. Any outside attempt to infer an internal state will always be prone to biases. In spite of this, I decided to explore the host of my only social media profile, Facebook. Starting out very similarly to Google, I persisted in scrolling through thousands upon thousands of David Songs. I surrendered quicker this time and opened my public Facebook profile. At first glance, it’s obvious that I’m either not a frequent user of Facebook or I don’t update my profile regularly. My current profile picture promotes a school event that happened over a year ago. The last photo containing my face was posted in 2018 and I’ve only posted three in total that actually show myself. The content of my profile pictures range from a random illustration of a Magikarp to filters supporting Star Wars and Paris after the 2015 terrorist attacks. I also have things I’ve “liked” visible on my profile, most are school-related and some are of random interests like video games. Putting it all together, my Facebook profile is stereotypical of someone inactive on social media and doesn’t accurately illustrate my current interests or identity. It’s obvious that without an up-to-date profile, my current self wouldn’t be well represented. But is an accurate depiction even possible? Trying out new selves is a natural part of identity formation. If stability was never guaranteed from the beginning, a static digital identity could never capture that fleeting existence.

Outside of Facebook, I have no social media presence whatsoever. It’s a fair assessment to make that outside of my advertising data and random voting records, I don’t have a digital identity. In many instances, I’ve debated making some type of social media profile and committing to using it frequently. Yet this was never actualized for several reasons. Starting in 2015, I primarily began using Reddit to interact with online communities, these typically revolved around depending on what games I played. The friends I surrounded myself with also used social media minimally. Rather than socializing with my peers on social media, video games became an alternative replacement for building a network. I formed many of my highschool friendships through gaming which inadvertently contributed to my nonexistent adaptation of social media. By finding online alternatives and staying active in after-school extracurriculars, I was able to circumvent the need of having an online presence to stay connected. As time passed, I observed an increasing number of people creating accounts and sharing their identities while I stayed apathetic. Perhaps as social media use normalized over time, I disliked admitting I didn’t have one and conjured more justifications. It became easier and easier to ignore social media because the longer I waited, the more justified my initial cause wrongfully became. My worries culminated during my first year of college when my roommate admitted to thinking less of me at first for “not having an Instagram account,” a blunt reminder that my digital identity’s journey wasn’t the norm.

Concluding Thoughts

Today, I’m ultimately content living without social media. The online representation of my identity through social media isn’t fully accurate but I certainly don’t lack one outside of the Internet. Though it wasn’t my intent to not have a well-defined digital identity, it’s ironically affected my actual identity. That doesn’t mean you can characterize me as someone intentionally refusing to interact with society, but the legitimacy of that claim itself reflects the extent of how pivotal digital identities have become to our daily lives. The shifting standards for how people should be identified in society has real consequences for those that don’t conform, which I witnessed firsthand. Foreigners, inexperienced Internet users, and the elderly are just some examples of many potentially left behind. My experience with the Google searching algorithm was another direct example of this. Although some factors were outside my control, by not interacting more with societally-valued aspects of my digital identity like LinkedIn, it became less visible, potentially affecting my actual career prospects. From VoterRecords.com, I learned that actions outside of technology can also affect your digital identity; it’s become nearly impossible to fully grasp how much of your information is controlled by data brokers. Through my experiences with social media, I understood that our digital identities are never truly authentic representations of us, yet they’re judged oppositely. As I once experienced firsthand, there are social consequences for not following that paradigm of staying connected. Paralleling the age-old debate between free will versus environment, the decision to create and maintain digital identities isn’t entirely up to us. Whether data brokers gather information unbeknownst to us or society incentivizes our continued technological interaction, digital identities are inauthentic existences. They don’t represent us but we paradoxically take ownership of them, lest we suffer the consequences. Ultimately, representing one’s identity is fundamental to the human experience and while digital equivalents can be of use, they should never be required nor considered a replacement.