Difference between revisions of "Cybersecurity Law in Vietnam"

(→Prohibited Content) |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | The '''Cybersecurity Law''' was revolutionarily instituted by the Vietnamese National Assembly on January 1, 2019.<ref name="hlda">“Update: Vietnam's New Cybersecurity Law.” HL Chronicle of Data Protection, 14 Nov. 2018, www.hldataprotection.com/2018/11/articles/international-eu-privacy/update-vietnams-new-cybersecurity-law/.</ref> The new law imposes extreme restrictions on user freedoms online, in hopes of preventing cyber crimes. Defaming the government, spreading false information, and promoting radical ideas | + | The '''Cybersecurity Law''' was revolutionarily instituted by the Vietnamese National Assembly on January 1, 2019.<ref name="hlda">“Update: Vietnam's New Cybersecurity Law.” HL Chronicle of Data Protection, 14 Nov. 2018, www.hldataprotection.com/2018/11/articles/international-eu-privacy/update-vietnams-new-cybersecurity-law/.</ref> The new law imposes extreme restrictions on user freedoms online, in hopes of preventing cyber crimes. Defaming the government, spreading false information, and promoting radical ideas online about the government must be removed immediately.<ref name="freedomhouse">“Vietnam.” Vietnam Country Report, 11 Feb. 2019, freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-net/2018/vietnam.</ref>. Moreover, social media companies and other online services have to comply to new data-localization guidelines, which require them to collect Vietnamese user data, and to report the data to authorities when requested.<ref name="hlda"/> The implementation of the Cybersecurity Law has caused significant backlash from online service providers and the Vietnamese people for infringing on the privacy rights of Vietnam's citizens. The lack of privacy limits one's anonymity online also giving people a sense of being surveilled. |

=== Internet Censorship In Vietnam === | === Internet Censorship In Vietnam === | ||

Revision as of 13:04, 19 April 2019

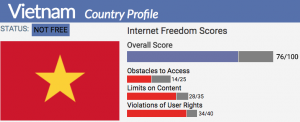

The Cybersecurity Law was revolutionarily instituted by the Vietnamese National Assembly on January 1, 2019.[1] The new law imposes extreme restrictions on user freedoms online, in hopes of preventing cyber crimes. Defaming the government, spreading false information, and promoting radical ideas online about the government must be removed immediately.[2]. Moreover, social media companies and other online services have to comply to new data-localization guidelines, which require them to collect Vietnamese user data, and to report the data to authorities when requested.[1] The implementation of the Cybersecurity Law has caused significant backlash from online service providers and the Vietnamese people for infringing on the privacy rights of Vietnam's citizens. The lack of privacy limits one's anonymity online also giving people a sense of being surveilled.

Contents

Internet Censorship In Vietnam

Vietnam has had strict internet regulations since 2013, and nearly 54% of the population is online.[3] Vietnam uses a combination of firewalls, controls, and other forms of censorship on the internet to limit anti-government propaganda and other harmful behavior.[4]

Many websites containing information about democracy and other forms of freedom are blocked. Whenever deemed necessary, authorities can restrict internet access to citizens. Their efforts are not only limited to technical controls: Vietnam implements legislation and provides education that furthers their security intentions.[5]. The rigor of Vietnam’s internet censorship follows similar patterns to those of its neighbor, China. Punishments for not complying to Vietnam's internet standards include internet restriction, blockage from telecommunication networks, or, worse, jail-time.

Social Media Companies

Prohibited Content

More than half of Vietnam’s population are social media users. The most popular social media sites in Vietnam are Facebook, YouTube, and Google.[6] The main attraction of social media being the absence of government regulation, making it one of the few platforms for activists to express their dissents. The new Cybersecurity law requires social media companies to remove or block any information considered toxic by the government within 24 hours, as instructed by the authorities.[2] Most prohibited content denounces the Vietnam regime or promotes radical ideas. In 2017, prior to the law, Google had to remove over 6000 YouTube videos.[6] Leading authorities to ask Facebook to remove hundreds of accounts. Other blogging or messaging platforms were also prohibited throughout Vietnam, and bloggers have even been arrested for stating their views openly online.

Data Localization Policies

The Cybersecurity law also requires prominent social media companies such as Facebook and Google to build offices in Vietnam to provide local data storage.[6] Currently, both companies serve Vietnam from their offices in Singapore. The data localization policy specifies that social media companies must collect personal data on users that are Vietnamese citizens. Authorities may also require companies to store information including a user's name, contact information, relationships, or online activities. The government can also force companies to store even more invasive data, such as a user's job title, medical records, and address.[1] This information must be surrendered to the government when requested. The Cybersecurity law also states that the government determines how long social media companies must store this data. Some social media companies believe the new data localization policies are a privacy violation, because they have to choose between complying to the cybersecurity law or following their own terms of service, which are generally much more open.[1]

Vietnamese Citizens

The actions of Vietnamese citizens are closely surveilled and monitored online. Any offensive commentary posted about the Vietnam regime can be subject to punishment under the Cybersecurity law. Previously, online forums and blogs were one of the only ways for Vietnamese activists to spread their beliefs to a large audience. Radical bloggers and activists were still occasionally given harsh prison sentences for posting slander online, but there were no clear legislative policies. Blogger Hoang Duc Binh had received the longest sentence to date and suffered 14 years in prison.[2]. Under the new law, any blogger caught making an offensive comment online can be convicted of a crime or restricted internet access. The punishment for the crime varies based on the severity of the statement. The government implemented a 10,000 person military unit to regulate offensive content online.[2] The government’s ability to manipulate the information posted by a Vietnamese citizen can be seen as an unauthorized invasion of personal information, and thus a breach of privacy, according to Floridi and many others.[7] The government shows no respect to this type of privacy, especially in regard to non-conforming opinions and commentary.

Ethical Implications

Surveillance

Across the world, Vietnam's cybersecurity law has been denounced repeatedly for its absence of privacy protection for the Vietnamese people. Many critics argue the law exhibits zero regard for privacy on the internet, and has destructive outcomes for freedom of expression.[8] Every act by citizens and online service providers is closely monitored and scrutinized. Constant surveillance in a public space produces ambiguity on who is monitoring actions and when.[9] Surveillance creates a significant loss of freedom because it changes a person’s experience in that space, as they self-censor. This has devastating consequences for privacy because a person’s sense of self-ownership is restricted, which affects their identity.[9] Communities online used to be the only way to escape from Vietnam’s oppressive climate, but now even this outlet is tainted. Many believe the Cybersecurity law is solely to protect the government’s monopoly, rather than for its stated purpose for cyber security.[8]

Anonymity

The government’s requirement that online service providers must collect excessive amounts of data on users greatly limits an individual’s capacity to be anonymous online. So much data is collected about a user's actions and relationships, that, if coordinated, can easily result in identifiability.[7] When examined individually, a user’s actions can be difficult to trace back to them. However, when grouped together, these actions can reveal identifying characteristics about the user.[7] Moreover, in time a pattern may form from a user’s online activity, which can particularly reveal personal details about their life. By using sophisticated data analysis tactics, the government can identity their citizens who do not conform to their preferred beliefs and standards. Anonymity provides safety, freedom, and security. Users value anonymity as a means of maintaining privacy and the Cybersecurity law restricts this ability.

Policy Across Borders

In the past, inconsistent legislation and regulations surrounding internet conduct across different countries has led to a number of complicated ethical questions. Without a global standard to define the ethical principles of internet use across borders, it can be difficult to negotiate the laws and regulations between conflicting ideologies of two or more countries. Recently, a group of individuals formed to define a code of ethics for Google's "right to be forgotten" policy. [10] Luciano Floridi, one of the members of the board that Google constructed, wrote an article on the ethical issues that were confronted in their discussion. [10] One of the issues mentioned in his article and that the board confronted early on dealt with how policies regarding what justifies a valid delink request should translate across borders. In the future, a similar issue of how differing policies may be handled in Vietnam's relations with countries may prove to be a difficult problem to solve.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 “Update: Vietnam's New Cybersecurity Law.” HL Chronicle of Data Protection, 14 Nov. 2018, www.hldataprotection.com/2018/11/articles/international-eu-privacy/update-vietnams-new-cybersecurity-law/.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 “Vietnam.” Vietnam Country Report, 11 Feb. 2019, freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-net/2018/vietnam.

- ↑ Luong, Dien. “Vietnam's Internet Is in Trouble.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 19 Feb. 2018,www.washingtonpost.com/news/theworldpost/wp/2018/02/19/vietnam-internet/?utm_term=.fb2b4d4954d8.

- ↑ Warf, B. GeoJournal (2011) 76: 1. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-010-9393-3

- ↑ Subramanian, Ramesh, The Growth of Global Internet Censorship and Circumvention: A Survey (October 31, 2011). Communications of the International Information Management Association (CIIMA), Volume 11, Issue 2, 2011.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Nguyen, Mai. “Vietnam Set to Tighten Clamps on Facebook and Google, Threatening...” Reuters, Thomson Reuters, 18 May 2018, www.reuters.com/article/us-vietnam-socialmedia-insight/vietnam-set-to-tighten-clamps-on-facebook-and-google-threatening-dissidents-idUSKCN1IJ1CU.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 “Privacy - Informational Friction .” The 4th Revolution: How the Infosphere Is Reshaping Human Reality, by Luciano Floridi, Oxford University Press, 2016.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Nguyen, Thoi. “Vietnam's Controversial Cybersecurity Law Spells Tough Times for Activists.” The Diplomat, The Diplomat, 4 Jan. 2019, thediplomat.com/2019/01/vietnams-controversial-cybersecurity-law-spells-tough-times-for-activists/.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Patton, J.W. Ethics and Information Technology-Protecting Privacy in Public? (2000) 2: 181. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010057606781

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 “Should You Have The Right To Be Forgotten On Google? Nationally, Yes. Globally, No.” 2015