Difference between revisions of "Cryptocurrency and its Impact on the Environment"

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

==Environmental Impact of Bitcoin== | ==Environmental Impact of Bitcoin== | ||

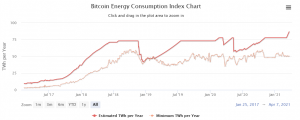

Bitcoin is thought to consumer 707kwH per transaction, and according to a University of Cambridge analysis, it is estimated that bitcoin mining consumers 121.36 terawatt-hours a year, which is more than all of Argentina consumes, or more than the consumption of Google, Apple, Facebook, and Microsoft combined <ref>20, R. C. |S., Cho, R., Dexfolio, J., S, E., Ishita, Nerad, S., Joad, T., & Dallaire, L. (2021, September 16). Bitcoin's impacts on climate and the environment. State of the Planet. Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://news.climate.columbia.edu/2021/09/20/bitcoins-impacts-on-climate-and-the-environment/ </ref>. Between 2015 and March of 2021, Bitcoin energy consumption had nearly increased almost 62-fold, and only about 39 percent of this energy comes from hydropower, which can have harmful impacts on ecosystems and biodiversity. Many miners within the US are converting abandoned factories and power plants into large bitcoin mining facilities <ref>20, R. C. |S., Cho, R., Dexfolio, J., S, E., Ishita, Nerad, S., Joad, T., & Dallaire, L. (2021, September 16). Bitcoin's impacts on climate and the environment. State of the Planet. Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://news.climate.columbia.edu/2021/09/20/bitcoins-impacts-on-climate-and-the-environment/ </ref>. One example of this is Greenidge Generation, which was a coal power plant, which has not been transformed into a bitcoin mining facility running on natural gas. AS it became one of the largest cryptocurrency miners in the United States, its greenhouse gas emissions increased almost 10x between 2019 and 2020. Globally, Bitcoin's power consumption has implications for the goals outlined in the Paris Accord as it translates into an estimated 22 to 22.9 million metric tons of CO2 emissions each year <ref>20, R. C. |S., Cho, R., Dexfolio, J., S, E., Ishita, Nerad, S., Joad, T., & Dallaire, L. (2021, September 16). Bitcoin's impacts on climate and the environment. State of the Planet. Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://news.climate.columbia.edu/2021/09/20/bitcoins-impacts-on-climate-and-the-environment/ </ref>. This is nearly equivalent to the energy use of almost 2.6 billion homes a year. With more mining moving to the U.S. and other countries, this amount could grow even larger unless more renewable energy is used. | Bitcoin is thought to consumer 707kwH per transaction, and according to a University of Cambridge analysis, it is estimated that bitcoin mining consumers 121.36 terawatt-hours a year, which is more than all of Argentina consumes, or more than the consumption of Google, Apple, Facebook, and Microsoft combined <ref>20, R. C. |S., Cho, R., Dexfolio, J., S, E., Ishita, Nerad, S., Joad, T., & Dallaire, L. (2021, September 16). Bitcoin's impacts on climate and the environment. State of the Planet. Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://news.climate.columbia.edu/2021/09/20/bitcoins-impacts-on-climate-and-the-environment/ </ref>. Between 2015 and March of 2021, Bitcoin energy consumption had nearly increased almost 62-fold, and only about 39 percent of this energy comes from hydropower, which can have harmful impacts on ecosystems and biodiversity. Many miners within the US are converting abandoned factories and power plants into large bitcoin mining facilities <ref>20, R. C. |S., Cho, R., Dexfolio, J., S, E., Ishita, Nerad, S., Joad, T., & Dallaire, L. (2021, September 16). Bitcoin's impacts on climate and the environment. State of the Planet. Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://news.climate.columbia.edu/2021/09/20/bitcoins-impacts-on-climate-and-the-environment/ </ref>. One example of this is Greenidge Generation, which was a coal power plant, which has not been transformed into a bitcoin mining facility running on natural gas. AS it became one of the largest cryptocurrency miners in the United States, its greenhouse gas emissions increased almost 10x between 2019 and 2020. Globally, Bitcoin's power consumption has implications for the goals outlined in the Paris Accord as it translates into an estimated 22 to 22.9 million metric tons of CO2 emissions each year <ref>20, R. C. |S., Cho, R., Dexfolio, J., S, E., Ishita, Nerad, S., Joad, T., & Dallaire, L. (2021, September 16). Bitcoin's impacts on climate and the environment. State of the Planet. Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://news.climate.columbia.edu/2021/09/20/bitcoins-impacts-on-climate-and-the-environment/ </ref>. This is nearly equivalent to the energy use of almost 2.6 billion homes a year. With more mining moving to the U.S. and other countries, this amount could grow even larger unless more renewable energy is used. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <ref name="Bitcoin Statistics"> “Bitcoin by Numbers: 21 Statistics That Reveal Growing Demand for the Cryptocurrency.” Bitcoin News, 13 Nov. 2017, https://news.bitcoin.com/bitcoin-numbers-21-statistics-reveal-growing-demand-cryptocurrency/.</ref>. | ||

| + | [[File:Bitcoin.png|thumbnail|right]] | ||

==Water Issues and E-Waste== | ==Water Issues and E-Waste== | ||

| Line 19: | Line 22: | ||

| − | Some other ideas for the greening of cryptocurrencies involve moving bitcoin operations in close proximity to oil fields, where the miners can tap into the waste that methane gas emits, pipe it into generators, and use that power for bitcoin mining. There are also some mines that are planning to be built in West Texas, where wind power is abundant. Since there is sometimes more powerful than transmission lines can handle, bitcoin mining situated near wind farms can use their excess energy<ref>20, R. C. |S., Cho, R., Dexfolio, J., S, E., Ishita, Nerad, S., Joad, T., & Dallaire, L. (2021, September 16). Bitcoin's impacts on climate and the environment. State of the Planet. Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://news.climate.columbia.edu/2021/09/20/bitcoins-impacts-on-climate-and-the-environment/ </ref>. R.A. Farrokhnia, Columbia Business School professor and executive director of the Columbia Fintech Initiative states that some of the ideas require very high upfront capital expenditures, and as a result, they might not be pragmatic<ref>20, R. C. |S., Cho, R., Dexfolio, J., S, E., Ishita, Nerad, S., Joad, T., & Dallaire, L. (2021, September 16). Bitcoin's impacts on climate and the environment. State of the Planet. Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://news.climate.columbia.edu/2021/09/20/bitcoins-impacts-on-climate-and-the-environment/ </ref>. Farrokhnia fears that as soon as bitcoin prices drop below a certain threshold, then the expensive solutions would no longer be feasible, as she begs the question "Who in reality would make those investments given the volatility in the price of bitcoin and the uncertainty about the future of it?" <ref>20, R. C. |S., Cho, R., Dexfolio, J., S, E., Ishita, Nerad, S., Joad, T., & Dallaire, L. (2021, September 16). Bitcoin's impacts on climate and the environment. State of the Planet. Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://news.climate.columbia.edu/2021/09/20/bitcoins-impacts-on-climate-and-the-environment/ </ref>. | + | Some other ideas for the greening of cryptocurrencies involve moving bitcoin operations in close proximity to oil fields, where the miners can tap into the waste that methane gas emits, pipe it into generators, and use that power for bitcoin mining. There are also some mines that are planning to be built in West Texas, where wind power is abundant. Since there is sometimes more powerful than transmission lines can handle, bitcoin mining situated near wind farms can use their excess energy<ref>20, R. C. |S., Cho, R., Dexfolio, J., S, E., Ishita, Nerad, S., Joad, T., & Dallaire, L. (2021, September 16). Bitcoin's impacts on climate and the environment. State of the Planet. Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://news.climate.columbia.edu/2021/09/20/bitcoins-impacts-on-climate-and-the-environment/ </ref>. R.A. Farrokhnia, Columbia Business School professor and executive director of the Columbia Fintech Initiative states that some of the ideas require very high upfront capital expenditures, and as a result, they might not be pragmatic<ref>20, R. C. |S., Cho, R., Dexfolio, J., S, E., Ishita, Nerad, S., Joad, T., & Dallaire, L. (2021, September 16). Bitcoin's impacts on climate and the environment. State of the Planet. Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://news.climate.columbia.edu/2021/09/20/bitcoins-impacts-on-climate-and-the-environment/ </ref>. Farrokhnia fears that as soon as bitcoin prices drop below a certain threshold, then the expensive solutions would no longer be feasible, as she begs the question "Who in reality would make those investments given the volatility in the price of bitcoin and the uncertainty about the future of it?" <ref>20, R. C. |S., Cho, R., Dexfolio, J., S, E., Ishita, Nerad, S., Joad, T., & Dallaire, L. (2021, September 16). Bitcoin's impacts on climate and the environment. State of the Planet. Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://news.climate.columbia.edu/2021/09/20/bitcoins-impacts-on-climate-and-the-environment/ </ref>. |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ==Human Health Impacts of Cryptocurrency Mining== | ||

| + | Expanding upon previously calculated energy use patterns for mining four prominent cryptocurrencies (Bitcoin, Ethereum, Litecoin, and Monero), certain studies estimate the per coin economic damages of air pollution emissions and associated human mortality and climate impacts of mining such Cryptocurrencies within the US and China. Results from these studies indicate that in 2018 alone, each $1 of Bitcoin value created was responsible for $0.49 in health and climate damages in the US and #0.37 in China.<ref>Andrew L. Goodkind, Benjamin A. Jones, Robert P. Berrens, Cryptodamages: Monetary value estimates of the air pollution and human health impacts of cryptocurrency mining, Energy Research & Social Science, Volume 59, 2020, 101281, ISSN 2214-6296, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2019.101281. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2214629619302701)</ref>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

[[Category:BlueStar2018]] | [[Category:BlueStar2018]] | ||

Revision as of 06:11, 30 January 2022

Contents

Origins

In 2008, an anonymous person under the pseudonym, Satoshi Nakomoto, published a paper titled "Bitcoin: A Peer to Peer Electronic Cash System"[3]. On January 3rd, 2009, Satoshi mined the genesis block of the Bitcoin blockchain. The Bitcoin protocol is open source code and has received contributions from numerous developers including, most notably, Hal Finney, Nick Szabo, and Gavin Andresen. In the years since, many other projects have been released that utilize Bitcoin's source code, as well as many other cryptocurrencies that have developed their own blockchain. These are known as altcoins.

Environmental Impact of Bitcoin

Bitcoin is thought to consumer 707kwH per transaction, and according to a University of Cambridge analysis, it is estimated that bitcoin mining consumers 121.36 terawatt-hours a year, which is more than all of Argentina consumes, or more than the consumption of Google, Apple, Facebook, and Microsoft combined [4]. Between 2015 and March of 2021, Bitcoin energy consumption had nearly increased almost 62-fold, and only about 39 percent of this energy comes from hydropower, which can have harmful impacts on ecosystems and biodiversity. Many miners within the US are converting abandoned factories and power plants into large bitcoin mining facilities [5]. One example of this is Greenidge Generation, which was a coal power plant, which has not been transformed into a bitcoin mining facility running on natural gas. AS it became one of the largest cryptocurrency miners in the United States, its greenhouse gas emissions increased almost 10x between 2019 and 2020. Globally, Bitcoin's power consumption has implications for the goals outlined in the Paris Accord as it translates into an estimated 22 to 22.9 million metric tons of CO2 emissions each year [6]. This is nearly equivalent to the energy use of almost 2.6 billion homes a year. With more mining moving to the U.S. and other countries, this amount could grow even larger unless more renewable energy is used.

[7].

Water Issues and E-Waste

Power plants, such as Greenidge, also happen to consume large amounts of water annually. Greenidge, specifically, draws up to 139 million gallons of freshwater each day, and even discharges some water that is 30 to 50 degrees hotter than the lake's average temperature[8] . This can endanger the lake's natural ecosystem, as well as the plant's large intake pipes killing larvae, fish, and other wildlife. The e-waste problem also begs another ethical dilemma. Miners search for the most efficient hardware, which can become obsolete almost every year, and cannot be reprogrammed for other purposes. This leads to an estimation of 11.5 kilotons of e-waste each year from the Bitcoin network alone.

Some Possible Solutions

Tesla CEO Elon Musk met with the CEOs of the top North American crypto mining companies about their energy use, which led to the creation of a new Bitcoin Mining Council in order to promote energy transparency[9]. Another initiative is the Crypto Climate Accord, which is supported by 40 projects, with the goal of allowing blockchains to run on 100 percent renewable energy by 2025 and have the entire cryptocurrency industry achieve net-zero emissions by 2040. This can be achieved by attempting to decarbonize the blockchains by using the most efficient validation methods, specifically to situate work systems in areas with excess renewable energy that can be used. The encouragement of purchasing certificates can also support renewable energy generators, much like carbon offsets support green projects.

Etheruem is also aiming to reduce its energy by almost 99.5 percent by 2022, by transitioning to the proof of stake method, which does not require computational power to solve puzzles for the right to verify transactions. The system ensures security because if validators cheat, they lose their stake and are banned from the network. When prices increase, so does the network security, but the energy demands remain constant. Some worry, however, is that the proof of stake method could give people with the most ETH more power, leading to a decentralized system.

Some other ideas for the greening of cryptocurrencies involve moving bitcoin operations in close proximity to oil fields, where the miners can tap into the waste that methane gas emits, pipe it into generators, and use that power for bitcoin mining. There are also some mines that are planning to be built in West Texas, where wind power is abundant. Since there is sometimes more powerful than transmission lines can handle, bitcoin mining situated near wind farms can use their excess energy[10]. R.A. Farrokhnia, Columbia Business School professor and executive director of the Columbia Fintech Initiative states that some of the ideas require very high upfront capital expenditures, and as a result, they might not be pragmatic[11]. Farrokhnia fears that as soon as bitcoin prices drop below a certain threshold, then the expensive solutions would no longer be feasible, as she begs the question "Who in reality would make those investments given the volatility in the price of bitcoin and the uncertainty about the future of it?" [12].

Human Health Impacts of Cryptocurrency Mining

Expanding upon previously calculated energy use patterns for mining four prominent cryptocurrencies (Bitcoin, Ethereum, Litecoin, and Monero), certain studies estimate the per coin economic damages of air pollution emissions and associated human mortality and climate impacts of mining such Cryptocurrencies within the US and China. Results from these studies indicate that in 2018 alone, each $1 of Bitcoin value created was responsible for $0.49 in health and climate damages in the US and #0.37 in China.[13].

References

- ↑ https://www.investopedia.com/terms/c/cryptocurrency.asp

- ↑ https://news.climate.columbia.edu/2021/09/20/bitcoins-impacts-on-climate-and-the-environment/

- ↑ Nakamoto, S. (2018). Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System (pp. 1-9). www.bitcoin.org. Retrieved from https://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf

- ↑ 20, R. C. |S., Cho, R., Dexfolio, J., S, E., Ishita, Nerad, S., Joad, T., & Dallaire, L. (2021, September 16). Bitcoin's impacts on climate and the environment. State of the Planet. Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://news.climate.columbia.edu/2021/09/20/bitcoins-impacts-on-climate-and-the-environment/

- ↑ 20, R. C. |S., Cho, R., Dexfolio, J., S, E., Ishita, Nerad, S., Joad, T., & Dallaire, L. (2021, September 16). Bitcoin's impacts on climate and the environment. State of the Planet. Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://news.climate.columbia.edu/2021/09/20/bitcoins-impacts-on-climate-and-the-environment/

- ↑ 20, R. C. |S., Cho, R., Dexfolio, J., S, E., Ishita, Nerad, S., Joad, T., & Dallaire, L. (2021, September 16). Bitcoin's impacts on climate and the environment. State of the Planet. Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://news.climate.columbia.edu/2021/09/20/bitcoins-impacts-on-climate-and-the-environment/

- ↑ “Bitcoin by Numbers: 21 Statistics That Reveal Growing Demand for the Cryptocurrency.” Bitcoin News, 13 Nov. 2017, https://news.bitcoin.com/bitcoin-numbers-21-statistics-reveal-growing-demand-cryptocurrency/.

- ↑ 20, R. C. |S., Cho, R., Dexfolio, J., S, E., Ishita, Nerad, S., Joad, T., & Dallaire, L. (2021, September 16). Bitcoin's impacts on climate and the environment. State of the Planet. Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://news.climate.columbia.edu/2021/09/20/bitcoins-impacts-on-climate-and-the-environment/

- ↑ 20, R. C. |S., Cho, R., Dexfolio, J., S, E., Ishita, Nerad, S., Joad, T., & Dallaire, L. (2021, September 16). Bitcoin's impacts on climate and the environment. State of the Planet. Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://news.climate.columbia.edu/2021/09/20/bitcoins-impacts-on-climate-and-the-environment/

- ↑ 20, R. C. |S., Cho, R., Dexfolio, J., S, E., Ishita, Nerad, S., Joad, T., & Dallaire, L. (2021, September 16). Bitcoin's impacts on climate and the environment. State of the Planet. Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://news.climate.columbia.edu/2021/09/20/bitcoins-impacts-on-climate-and-the-environment/

- ↑ 20, R. C. |S., Cho, R., Dexfolio, J., S, E., Ishita, Nerad, S., Joad, T., & Dallaire, L. (2021, September 16). Bitcoin's impacts on climate and the environment. State of the Planet. Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://news.climate.columbia.edu/2021/09/20/bitcoins-impacts-on-climate-and-the-environment/

- ↑ 20, R. C. |S., Cho, R., Dexfolio, J., S, E., Ishita, Nerad, S., Joad, T., & Dallaire, L. (2021, September 16). Bitcoin's impacts on climate and the environment. State of the Planet. Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://news.climate.columbia.edu/2021/09/20/bitcoins-impacts-on-climate-and-the-environment/

- ↑ Andrew L. Goodkind, Benjamin A. Jones, Robert P. Berrens, Cryptodamages: Monetary value estimates of the air pollution and human health impacts of cryptocurrency mining, Energy Research & Social Science, Volume 59, 2020, 101281, ISSN 2214-6296, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2019.101281. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2214629619302701)