Difference between revisions of "Censorship in China"

(→Purpose) |

(→Purpose) |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

==The Great Firewall== | ==The Great Firewall== | ||

===Purpose=== | ===Purpose=== | ||

| − | The Great Firewall of China, also known as the [[Wikipedia:Golden Shield Project|Golden Shield Project]], is a set of technologies and methods with the overall goal of | + | The Great Firewall of China, also known as the [[Wikipedia:Golden Shield Project|Golden Shield Project]], is a set of technologies and methods with the overall goal of censorship. The Great Firewall itself has not been officially acknowledged the existence or publically exposed the implementation of the Great Firewall program. Methods for internet censorship include bandwidth throttling, keyword filtering, and blocking access to certain selected foreign websites. These websites include but are not limited to Facebook, Twitter, Google, and Wikipedia. China's Great Firewall also seeks to regulate cross-border traffic by denying some foreign traffic coming onto their servers, as well as denying some traffic leaving China intended for foreign servers. Beyond the firewall, the government has also turned to shuttering publications or websites, and jailing dissident journalists, bloggers, and activists.<ref name="cfr">“Media Censorship in China.” Council on Foreign Relations, Council on Foreign Relations, www.cfr.org/backgrounder/media-censorship-china.</ref><br /> |

China uses a complex, technical process to filters through posts, videos, comments, and other forms of user generated content. Research done in 2014 showed that China allows for the criticisms of the state, its leaders, and their policies, whereas posts with collective action potential are much more likely to be censored. Censorship in China is used to muzzle those outside government who attempt to spur the creation of crowds for any reason — in opposition to, in support of, or unrelated to the government. The government allows the Chinese people to say whatever they like about the state, its leaders, or their policies, because talk about any subject unconnected to collective action is not censored. The value that Chinese leaders find in allowing and then measuring criticism by hundreds of millions of Chinese people creates actionable information for them, and, as a result, also for academic scholars and public policy analysts.<ref>King, Gary, et al. “Reverse-Engineering Censorship in China: Randomized Experimentation and Participant Observation.” Science, American Association for the Advancement of Science, 22 Aug. 2014, science.sciencemag.org/content/345/6199/1251722?casa_token=f8ofS6DrYqcAAAAA%3AvwldmGPv7KxV2DIX7Xt7NMKVhxYlZuCXOKzhfTjsEQ9xaCui3YRkUVhvA1EkkgGFc0LUVe0WaIEFLMA.</ref> | China uses a complex, technical process to filters through posts, videos, comments, and other forms of user generated content. Research done in 2014 showed that China allows for the criticisms of the state, its leaders, and their policies, whereas posts with collective action potential are much more likely to be censored. Censorship in China is used to muzzle those outside government who attempt to spur the creation of crowds for any reason — in opposition to, in support of, or unrelated to the government. The government allows the Chinese people to say whatever they like about the state, its leaders, or their policies, because talk about any subject unconnected to collective action is not censored. The value that Chinese leaders find in allowing and then measuring criticism by hundreds of millions of Chinese people creates actionable information for them, and, as a result, also for academic scholars and public policy analysts.<ref>King, Gary, et al. “Reverse-Engineering Censorship in China: Randomized Experimentation and Participant Observation.” Science, American Association for the Advancement of Science, 22 Aug. 2014, science.sciencemag.org/content/345/6199/1251722?casa_token=f8ofS6DrYqcAAAAA%3AvwldmGPv7KxV2DIX7Xt7NMKVhxYlZuCXOKzhfTjsEQ9xaCui3YRkUVhvA1EkkgGFc0LUVe0WaIEFLMA.</ref> | ||

Revision as of 23:29, 14 April 2019

Censorship in China is an issue that has prevailed through history, some of the most notable events include the burning of Confucian texts by Emperor Qin in the third century BCE, and the control of media during the Cultural Revolution.[1] Censorship is the suppression or prohibition of any parts of books, films, news, etc. that are considered obscene, politically unacceptable, or a threat to security.[2] With the rise of the internet, censorship in China has evolved to account for the new found freedom that the internet provides. China deployed an army of bots and millions of human censors to work around the clock and police daily activities.[3] This effort is commonly known as The Great Firewall. The Great Firewall brings with it a number of ethical concerns including restrictions to internet access and the need for legislation across borders.

Contents

The Great Firewall

Purpose

The Great Firewall of China, also known as the Golden Shield Project, is a set of technologies and methods with the overall goal of censorship. The Great Firewall itself has not been officially acknowledged the existence or publically exposed the implementation of the Great Firewall program. Methods for internet censorship include bandwidth throttling, keyword filtering, and blocking access to certain selected foreign websites. These websites include but are not limited to Facebook, Twitter, Google, and Wikipedia. China's Great Firewall also seeks to regulate cross-border traffic by denying some foreign traffic coming onto their servers, as well as denying some traffic leaving China intended for foreign servers. Beyond the firewall, the government has also turned to shuttering publications or websites, and jailing dissident journalists, bloggers, and activists.[4]

China uses a complex, technical process to filters through posts, videos, comments, and other forms of user generated content. Research done in 2014 showed that China allows for the criticisms of the state, its leaders, and their policies, whereas posts with collective action potential are much more likely to be censored. Censorship in China is used to muzzle those outside government who attempt to spur the creation of crowds for any reason — in opposition to, in support of, or unrelated to the government. The government allows the Chinese people to say whatever they like about the state, its leaders, or their policies, because talk about any subject unconnected to collective action is not censored. The value that Chinese leaders find in allowing and then measuring criticism by hundreds of millions of Chinese people creates actionable information for them, and, as a result, also for academic scholars and public policy analysts.[5]

Google had set up shop in mainland China in 2006, offering a version of its services that conformed to the government’s oppressive censorship policies. At the time, Google officials said they’d decided that the most ethical option was to offer some services - albeit restricted by China’s censors - to the enormous Chinese market, rather than leave millions of Internet users with limited access to information. However, in 2010, Google shut down its search engine and all operations within mainland China after a cyber attack, where it found that the Gmail accounts of a number of Chinese human-rights activists had been hacked. It moved all operations to Hong Kong, where all forms of both traditional and nontraditional media were uncensored at the time.[7] In 2018, Google revealed it had plans to launch a censored version of its search engine within China once again, named the "Dragonfly Project". Many employees protested, naming the "urgent moral and ethical issues" involved in the move.[8]

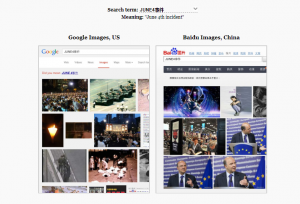

Google vs Baidu

Baidu is the largest search engine in China with over 2 billion users.[9] However, because of its censorship, the affordances of Google and Baidu are vastly different. This has led many to crack the firewall for access to tools such as Gmail and Google Scholar. The discrepancy between uncensored Google (USA) Images and Baidu Images in China is shown in the image here, in the search for the "Tiananmen Square Incident." The Google (USA) Images search yields vastly different results than the Baidu Images search, when in China, due to the censored content available on Baidu. However, with Google hoping to reenter mainland China, the search results may end up looking more similar to that of Baidu, while still affording China's users some of the access to Google-specific resources.[6]

Getting Past the Firewall

In an attempt to avoid the censorship of the Great Firewall, internet users over the years have found ways to circumvent the censors. Ultrasurf, Psiphon, and Freegate are popular software programs that allow Chinese users to set up proxy servers to avoid controls. While VPNs are also popular, the government crackdown on the systems have led users to devise other methods, including the insertion of new IP addresses into host files, Tor (a free software program for anonymity), or SSH tunnels, which route all internet traffic through a remote server.[4] These tactics help users to browse foreign sites freely, without the restriction of the Great Firewall's censorship.

DNS Cache Poisoning

The Domain Name System (DNS) is a hierarchical naming system that maps domain names to IP addresses. A correctly-operating DNS system is crucial to successful internet browsing. If the DNS fails, then users can not access the sites they are trying to reach because the domain name can't be mapped to the proper IP address. The Chinese government takes advantage of this in order to further impose censorship in China. DNS servers cache DNS requests. DNS cache poisoning is when the IP address for a domain name in the cache is swapped with a different IP address causing the user to be redirected to a different site than the one they were intending to reach. The Chinese government uses DNS cache poisoning to misdirect those requests to banned websites by sending them to the wrong IP address.[10] Since the Chinese government has access to the DNS cache servers, they can change any of the IP addresses they want in order to further impose censorship.

Banned Words/Concepts

There are lists of words and concepts that are permanently blacked out from appearing in any Chinese media. There are also lists of words and concepts that are temporarily blacked out of Chinese media, due to the context they are used in. An example of this was when the Chinese population turned to likening President Xi Jinping with Winnie the Pooh. All mentions of Winnie the Pooh or anything distinctly similar were banned from China. Another example of this was when the letter "N" was briefly banned in China. When word spread about the dropping of President Xi's term limits and his indefinite stay in power, the letter "N" was used like that of a mathematical equation where n>2 where n=term limits. Words such as "immortality" and "ascend the throne" were also banned in fear of civilian push back.[12]

Ethics

Association of Computing Machinery

The largest professional organisation for computing, the Association of Computing Machinery (ACM), recently updated its code of ethics. Many employees of large western companies are members of the ACM, meaning they have agreed to abide by this code. The code includes phrases such as “to contribute to society and to human well being”, “promoting human rights and protecting each individual’s right to autonomy”, and "computing professionals should take action to avoid creating systems or technologies that disenfranchise or oppress people”.[13] It has proven to be a challenge to follow the ACM code of ethics while also trying to forge a path into the Chinese market, which maintains the constraints of the Chinese firewall and other censorship policies. Moves such as the Dragonfly Project from Google have led people to question whether American companies are putting profits before ethics when conducting business in China. US lawmakers claimed that China's vast and lucrative market has prompted US companies to put ethical considerations to the side when adhering to Beijing's restrictive rules. US internet providers have defended their cooperation with the Chinese government, saying that restricted online access, while less than ideal, is still of great benefit to the vast majority of people in China.[14]

Ethics Across Borders

The ethical issues associated with censorship in China have raised a number of questions regarding how legislation and value systems among different cultures should interact with one another across borders, particularly via the internet. In his article: "Should You Have The Right To Be Forgotten On Google? Nationally, Yes. Globally, No.", Luciano Floridi, a professor of Philosophy at the University of Oxford, addresses some the ethical challenges associated with translating cultural values and ethics across international borders.[15] Floridi discusses his experience as a member of Google's Advisory Council on the Right to be Forgotten, whose purpose is to formulate a set of guidelines for determining what constitutes a valid "delink request" or removal of information from Google's search engines around the world. One issue that Floridi confronts early on in his article is the intersection of privacy and freedom of speech. In the case of China, a decision to censor certain portions of the internet, based on their own unique set of principles, represents a value system which clashes with a large portion of the western world, and with the idea of freedom of speech. What may seem as a blatant infringement on human civil rights within one country, may in another country be accepted as part of their culture. The ethical question of how international legislation should treat this issue remains unclear.

References

- ↑ "Burning Of Books And Burying Of Scholars." En.wikipedia.org. N. p., 2019. Web. 12 Apr. 2019.

- ↑ “Censorship | Definition of Censorship in English by Oxford Dictionaries.” Oxford Dictionaries | English, Oxford Dictionaries, en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/censorship.

- ↑ Hunt, Katie, and CY Xu. “China 'Employs 2 Million to Police Internet'.” CNN, Cable News Network, 7 Oct. 2013, www.cnn.com/2013/10/07/world/asia/china-internet-monitors/index.html.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 “Media Censorship in China.” Council on Foreign Relations, Council on Foreign Relations, www.cfr.org/backgrounder/media-censorship-china.

- ↑ King, Gary, et al. “Reverse-Engineering Censorship in China: Randomized Experimentation and Participant Observation.” Science, American Association for the Advancement of Science, 22 Aug. 2014, science.sciencemag.org/content/345/6199/1251722?casa_token=f8ofS6DrYqcAAAAA%3AvwldmGPv7KxV2DIX7Xt7NMKVhxYlZuCXOKzhfTjsEQ9xaCui3YRkUVhvA1EkkgGFc0LUVe0WaIEFLMA.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Sonnad, Nikhil. “See What China Sees When It Searches for ‘Tiananmen’ and Other Loaded Terms.” Quartz, Quartz, 11 Feb. 2015, qz.com/216829/see-what-china-sees-when-it-searches-for-tiananmen-and-other-loaded-terms/.

- ↑ Waddell, Kaveh. “Why Google Quit China-and Why It's Heading Back.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 19 Jan. 2016, www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2016/01/why-google-quit-china-and-why-its-heading-back/424482/.

- ↑ Theintercept. “Google Staff Tell Bosses China Censorship Is ‘Moral and Ethical’ Crisis.” The Intercept, 16 Aug. 2018, theintercept.com/2018/08/16/google-china-crisis-staff-dragonfly/.

- ↑ “Baidu.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 28 Mar. 2019, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baidu.

- ↑ Fox-Brewster, T. (2015, January 26). Accidental DDoS? How China's Censorship Machine Can Cause Unintended Web Blackouts. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/thomasbrewster/2015/01/26/china-great-firewall-causing-ddos-attacks/#3ff0341f6a47

- ↑ Haas, Benjamin. “China Bans Winnie the Pooh Film after Comparisons to President Xi.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 7 Aug. 2018, www.theguardian.com/world/2018/aug/07/china-bans-winnie-the-pooh-film-to-stop-comparisons-to-president-xi.

- ↑ Criss, Doug. “Why China Banned the Letter 'N'.” CNN, Cable News Network, 4 Mar. 2018, www.cnn.com/2018/03/01/asia/china-letter-ban-trnd/index.html.

- ↑ Flick, Catherine. “Why Google's Censored Search Engine for China Is Such an Ethical Minefield.” The Independent, Independent Digital News and Media, 8 Aug. 2018, www.independent.co.uk/life-style/gadgets-and-tech/features/china-great-firewall-google-online-internet-censorship-project-dragonfly-a8480016.html.

- ↑ Chinese Censorship, ethics.csc.ncsu.edu/speech/freedom/china/study.php.

- ↑ Floridi, Luciano "Should You Have The Right To Be Forgotten On Google? Nationally, Yes. Globally, No." 2015