Brave Browser

|

Brave Browser is an open-source browser application focused on prioritizing user privacy and democratizing online advertising. It has been developed using the Chromium web browser as a foundation, like Microsoft Edge and Opera.[1] Brave is specifically focused on the user privacy niche and blocks all ads and trackers by default.

Brave Software was co-founded in May 2015 by CEO Brendan Eich(creator of JavaScript and former CEO of Mozilla Corporation) and CTO Brian Bondy.[2]

Brave is headquartered in San Francisco, CA. As of February 2021, Brave Browser had over 25 million monthly active users. [3]

Key Features

Ad and Tracker Blocking

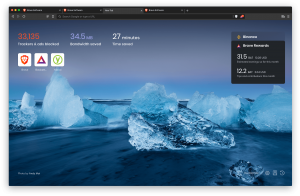

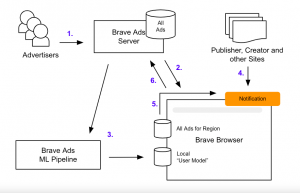

On any given tab, the browser has an option to enable and disable a display showing how many items have been blocked or modified on that particular page, such as cross-site trackers, connections upgraded to HTTPS, and scripts blocked.[4] The Brave Browser does not serve individual user browsing data on its servers, unlike most other browsers; instead, all user data is aggregated before being returned to Brave's servers. The ads and trackers that are blocked by default can also be customized by the user at any time. [5] However, user browsing data is still saved on users' local devices in order to ensure that ads that they may opt-in to see are still relevant. Brave also advertises that the fact that all ads are blocked, enabling faster browsing times for the user.

Basic Attention Token (BAT)

The Basic Attention Token (BAT) is an Ethereum-based token that can be traded on a wallet embedded in the browser itself. BAT is the unit of exchange used for browser features such as Brave Rewards. BAT had its initial coin offering (ICO) on May 31st, 2017.[6] In under 30 seconds, 1,000,000,000 BAT were sold for a total of 156,250 Ethereum.[7] BAT improves the efficiency of digital advertising by creating a new unit of exchange between publishers, advertisers, and users. BAT allows users to have better control over the ads they see online: users can block ads, pay to see different ads, or view ads and earn BAT tokens in exchange.[8] Advertisers also benefit from this model by achieving higher returns on advertising investment. This is delivered through better ad targeting (based on local user data) and reduced fraud.

Brave Rewards

Brave Rewards has a two-pronged benefit: it allows users to support their favorite content creators, and it allows users to earn money. For the former, Brave allows users to send their favorite content creators (YouTubers, Twitter users, blog owners, etc.) BAT, which can be converted to cash.[9] This practice is known as tipping. Users can choose to either set up recurring payments or make a one-time payment. For the latter benefit, users can choose to earn money by opting in to view ads. Rather than traditional banner ads, Brave displays its ads as a push notification that users can choose to interact with. The aim of this ad format is to create a more engaging ad experience that benefits all parties involved.

Currently, Brave has over 735,000 registered content creators with many notable names such as Philip DeFranco, The Washington Post, wikiHow, XXL, Vice, and The Guardian to name a few.[10] In the current e-commerce system, digital content creators receive an estimated half of their revenue due to users who use ad-blocks. In addition, many digital ad platforms are monopolized by Google, Facebook, and Amazon.[11] Thus, Brave Rewards is highly appealing to content creators as it attempts to equalize systemically disproportionate streams of revenue.

IPFS Integration

IPFS is the protocol that Brave uses instead of HTTP, which is what most browsers use. IPFS is known as a peer-to-peer protocol. This is because it uses distributed nodes near the user to send data. This can result in faster web browsing in certain areas. In contrast, HTTP has a centralized server that transmits data to users. This can be slow in some areas if the distance from the user to the server is far.

Another benefit to IPFS is that content restricted in some parts of the world, such as Turkey, Thailand, and China, are now available to them because of IPFS.[12]

Other Features

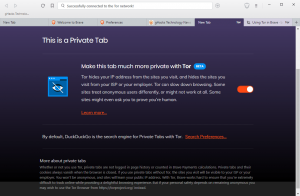

- Tor integration for anonymous browsing by concealing user location and usage information

- Auto-suggesting search terms and searching from the address bar

- Option to use DuckDuckGo for private window search

- Built-in password manager

- Fingerprinting prevention, cookie control, and HTTPS upgrading

- Support for most Chrome extensions

Planned Features

According to Brave’s BAT roadmap of 2021, Brave developers are aiming to increase crypto and decentralized finance (DeFi) accessibility by creating their own cryptocurrency wallet using Ethereum, an open-source blockchain technology.[13] The Brave Wallet will replace existing crypto wallets and have redesigned UI/UX as well as mobile support. A JavaScript Ethereum Provider API, used to connect web apps with Ethereum blockchain, will now be supplied to web pages by default and more options for buying crypto with fiat payment methods, currencies without use or instrinsic value, will be unlocked. Brave is also looking to support integrated NFT redemption usage (citation needed) within its browser and enable payment of transaction fees through BAT. To further spread DeFi, Brave is creating a new decentralized exchange aggregator with monetary incentives for Brave/Bat users. Aside from future optimizations in accountability and anonymity, to achieve their final endgame of building a Decentralized Web, Brave is researching BAT use in search engines, e-commerce, VPN, IPNS-verified content, and IPFS content pinning. According to public IPFS documentation, IPFS refers to “a distributed system for storing and accessing files, websites, applications, and data.”[14] IPFS uses content-based addressing while IPNS solves the issue of creating updatable addresses when content is updated. By tying BAT with multiple Decentralized Web systems, Brave is associating their browser and its reward system with other public efforts towards decentralization.

Ethical Considerations

Data Privacy

Data privacy while browsing online is a point of contention regarding Internet privacy in the modern day. Brave offers a robust feature list on metrics related to online privacy and data ethics. By keeping all data local and privatized, Brave does not monetize user data the way many browsers do. Instead, its primary revenue driver is its usage of BAT.[15] This business model allows them to monetize browsing while still returning 70% of revenue to Brave users themselves.[16] This allows for incentive alignment with users who are focused on privacy and Brave's monetization strategy and business model.

Online Advertising Ecosystem

The main concern with Brave's lack of individualized user collection is whether or not users would see relevant ads if they chose to opt-in to see ads in order to earn BAT. Although Brave does not collect individualized user data, it still practices machine learning on aggregated and anonymized data to ensure that ads users see are relevant for them.[17] By approaching advertising this way, Brave addresses common ethical concerns of monetization user behavior data, while still employing machine learning as an effective tool to display relevant ads. By choosing to implement ads in-app instead of using a third-party ad service, Brave Browser also eliminates the 3rd party ad broker and allows for revenue to be returned to the users.

User Expectations of Privacy

Users frequently have misconceptions about online privacy and how private browser modes work.[18] These include overestimating the function of private browser modes, such as assuming protection against ISP tracking of browsing history. A study has suggested this causes a negative impact on user privacy when using the Brave Browser, as users may engage differently when they expect a certain degree of anonymity.[19] This study also suggested that the new tab disclosure, which attempts to explain the difference between Brave’s two modes, is not effective at educating users on the impact on browsing privacy.

Failure of Privacy Promise

When Brave Browser was released, privacy was their main policy. By design, Brave Browser would inherently provide better privacy than other browsers. Brave addressed a big issue, surveillance capitalism, by “blocking trackers, invasive ads, and device fingerprinting.”[20] However, there have been some moments where Brave has failed to uphold their promises on privacy. There are multiple instances of the Brave Browser not delivering on its claim to provide privacy protection. One claim that has been found to be misleading is that all traces of browsing history are cleared on closure.[21] Fragments of browser data and activities are still accessible on RAM after closing the browser, though they are lost on computer shutdown. Another instance of compromised privacy was seen when a leak, originally seen in a [[wikipedia:patch|patch] ]introduced on October 14, 2020, was released in a stable build on November 20, 2020.[22] This leak revealed DNS information and server logs that could be traceable through high-level network access, such as law enforcement, posing a potential safety concern for users in regions with browsing restrictions. The leak was fixed on February 4, 2021 after being present in the stable build for 91 days. In another study, the Brave Browser was found to be vulnerable to the same attacks as Chrome, as it is built off of Chromium, which can reveal some browsing history information through CSS and Javascript weaknesses.[23]

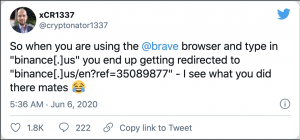

Another time that Brave Browser did not uphold their promises on privacy was their addition to auto-completing links to redirect users to affiliate links, “presumably for profit.” One user reported that when typing in “binance.us” to Brave Browser, it was auto-completed with "binance.us/en?ref=35089877." While the auto-completing of this link actually sent users to the right place, this incident rubbed users the wrong way. Because Brave Browser gives users the option to keep or remove ads, users were not pleased that Brave Browser was auto-completing links without notifying users that they were doing so.[25]

A third incident that Brave Browser had was because of their Tor browsing mode. Tor’s main objective is to conceal a user’s location when browsing online. Brave Browser had a bug that caused the website being visited to send a DNS query to your local device, which makes it possible for others to find your location. This bug was able to be verified by using an application, Wireshark, to analyze DNS traffic.[26]

Opposition

In the wake of its debut to the online realm, the Brave Browser found itself on the receiving end of a series of some serious flak from a coalition of major U.S. publishing companies known as the NAA that comprised firms such as Dow Jones, The Washington Post, The New York Times, and 14 others.[27] The core of the complaints made by these companies against Brave Browser revolved around what the companies claimed was illicit business practices on behalf of Brave. Specifically, the coalition cited the browser’s advertising-replacement policy as a system that infringes copyright, violates publishers’ terms of use, stimulates inequitable competitive practices, allows unsanctioned access to publishers’ websites, and breaches contracts with publishers.[27] In a letter to the Brave Software company, the NAA raised the above objections against Brave, describing its advertising policy as “blatantly illegal,” and stressed that the NAA was prepared to take extensive legal action against Brave for its alleged transgressions against the publishing industries. Within the same letter, the NAA forcefully and clearly refused to associate with Brave’s compensation model and denied Brave from using any aspect of the NAA’s companies, such as names, logos, and trademarks, to promote its business, believing that Brave’s “hijacking of the internet” would significantly hurt its source of revenue generated through traditional online advertising.[27] Brave responded to the criticisms expressed in the NAA’s letters by stating that the NAA had “fundamentally misunderstood” Brave’s advertising business plan.[27][28] Brave dismissed many of the NAA’s claims, describing them as unfounded, and reiterated their claim of how Brave's business model was for the greater good of publishing companies, web users, and the internet as whole.[27][28] Brave also re-explained its revenue strategy of 70% of revenue going to websites, 15% going to users, and 15% going to Brave, and re-emphasized how this strategy was not detrimental to the publishers’ revenue streams like they had so purported.[27][28]

Randall Rothenberg, CEO of the Interactive Advertising Bureau, also censured Brave’s advertising approach, charging the Brave Browser with being the product of dogmatic, self-righteous, hypocritical, wealthy sentiments and describing Brave’s advertisement policy as an affected front put on in order to better conceal “The Big Lie” hidden underneath the business’ true intentions.[27]

References

- ↑ Keizer, G. (2021, April 8). The Brave browser basics: what it does, how it differs from rivals. Computerworld. https://www.computerworld.com/article/3292619/the-brave-browser-basics-what-it-does-how-it-differs-from-rivals.html

- ↑ Bondy, B. (2019, November 13). The road to Brave 1.0. Brave. Retrieved March 11, 2021, from https://web.archive.org/web/20191119215054/https://brave.com/the-road-to-brave-one-dot-zero/

- ↑ Brave. (2021, February 2). Brave Passes 25 Million Monthly Active Users. Brave. Retrieved March 11, 2021, from https://brave.com/25m-mau/#:~:text=Brave%20Passes%2025%20Million%20Monthly%20Active%20Users

- ↑ Brave. (n.d.). Brave Features. Brave. Retrieved March 11, 2021, from https://brave.com/features/

- ↑ Brave. (n.d.). Brave Browser Privacy Policy. Brave. Retrieved April 20, 2021, from https://brave.com/privacy/browser/

- ↑ S., A. (2021, January 11). Basic Attention Token: The Complete Guide. BitDegree. Retrieved March 11, 2021, from https://www.bitdegree.org/crypto/basic-attention-token#:~:text=The%20BAT%20ICO%20(Initial%20Coin,was%20the%20ERC%2D20%20token.&text=The%20complete%20amount%20of%20the,1%2C5%20billion%20BAT%20tokens

- ↑ Russel, J. (2017, June 1). Former Mozilla CEO raises $35M in under 30 seconds for his browser startup Brave. TechCrunch. Retrieved March 11, 2021, from https://techcrunch.com/2017/06/01/brave-ico-35-million-30-seconds-brendan-eich/

- ↑ Buntinx, JP. (2018, February 7). What Is Basic Attention Token?. The Merkle. Retrieved March 11, 2021, from https://themerkle.com/what-is-basic-attention-token/

- ↑ Hodge, R. (2019, November 14). Brave 1.0 browser review: Browse faster and safer while ticking off advertisers. CNET. https://www.cnet.com/news/brave-1-0-browser-review-browse-faster-and-safer-while-ticking-off-advertisers/

- ↑ Brave. (2019). Brave Creators. Brave. Retrieved April 8, 2021, from https://creators.brave.com/

- ↑ Williams, R. (2019, August 23). Google: Publishers Lose Half Of Ad Revenue From Cookie Blocking. Publishing Insider. Retrieved April 8, 2021, from https://www.mediapost.com/publications/article/339624/google-publishers-lose-half-of-ad-revenue-from-co.html

- ↑ Bonifacic, I. (2021, January 19). "Brave browser now supports peer-to-peer IPFS protocol". Engadget. Retrieved April, 7, 2021 from https://www.engadget.com/brave-ipfs-update-190545662.html

- ↑ Brave. (2021, February 22). "BAT Roadmap 2.0". Brave. Retrieved April 8, 2021, from https://brave.com/bat-roadmap-2-0/

- ↑ Schilling, J. (2019, December 3). What is IPFS?. IPFS. Retrieved April 8, 2021, from https://docs.ipfs.io/concepts/what-is-ipfs/

- ↑ Keck, C. (2019, April 24). Brave Wants to Destroy the Ad Business by Paying You to Watch Ads in Its Web Browser. Gizmodo. Retrieved March 11, 2021, from https://gizmodo.com/brave-wants-to-destroy-the-ad-business-by-paying-you-to-1834283860.

- ↑ Ha, A. (2019, April 24). The Brave browser launches ads that reward users for viewing. TechCrunch. Retrieved March 11, 2021, from https://social.techcrunch.com/2019/04/24/brave-ads/]

- ↑ Brave. (2020, September, 3). An Introduction to Brave’s In-Browser Ads. Brave. Retrieved March 11, 2021, from https://brave.com/intro-to-brave-ads/

- ↑ Wu, Y., Gupta, P., Wei, M., Acar, Y., Fahl, S., & Ur, B. (2018, April). Your secrets are safe: How browsers' explanations impact misconceptions about private browsing mode. In Proceedings of the 2018 World Wide Web Conference (pp. 217-226).

- ↑ Fehlhaber, A. L., Acar, Y., Fahl, S., Gutfleisch, M., Theis, D., & Wallkötter, F. Poster: When Brave Hurts Privacy: Why Too Many Choices do More Harm Than Good.

- ↑ Krill P. (19 November 2019). 'Privacy first' Brave browser exits beta. InforWorld. Retrieved April 7, 2021, from https://bi-gale-com.proxy.lib.umich.edu/global/article/GALE%7CA606140924?u=umuser&sid=summon

- ↑ Mahlous, A. R., & Mahlous, H. Private Browsing Forensic Analysis: A Case Study of Privacy Preservation in the Brave Browser.

- ↑ Powers, B. (2021, February 23). Brave browser leak exposed user domain info for months. Coindesk. Retrieved March 18, 2021, from https://www.coindesk.com/brave-browser-leak-exposed-user-domain-info-months

- ↑ Smith, M., Disselkoen, C., Narayan, S., Brown, F., & Stefan, D. (2018). Browser history re: visited. In 12th {USENIX} Workshop on Offensive Technologies ({WOOT} 18).

- ↑ Davenport C. (7, June 2020). Brave Browser caught adding its own referral codes to some cryptocurrency trading sites. Android Police. Retrieved April 8, 2020, from https://www.androidpolice.com/2020/06/07/brave-browser-caught-adding-its-own-referral-codes-to-some-cryptcurrency-trading-sites/

- ↑ Engadget HD. (8, June 2020). Brave privacy browser 'mistake' added affiliate links to crypto URLs. Engadget HD. Retrieved April 7, 2021, from https://go-gale-com.proxy.lib.umich.edu/ps/i.do?p=STND&u=umuser&id=GALE%7CA655333954&v=2.1&it=r&sid=summon

- ↑ Abrams L. (19, February, 2021). Brave privacy bug exposes Tor onion URLs to your DNS provider. BleepingComputer. Retrieved April 7, 2021, from https://www.bleepingcomputer.com/news/security/brave-privacy-bug-exposes-tor-onion-urls-to-your-dns-provider/

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 27.4 27.5 27.6 O’Reilly, L. (2016, April 7). 'BLATANTLY ILLEGAL': 17 newspapers slam ex-Mozilla CEO's new ad-blocking browser. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/newspaper-publishers-send-cease-and-desist-to-brave-browser-2016-4

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Brave. (2016, April 7). Brave’s Response to the NAA: A Better Deal for Publishers. Brave. https://brave.com/braves-response-to-the-naa-a-better-deal-for-publishers/