Difference between revisions of "3D printing"

(→Ethical Concerns) |

(→Human Enhancement) |

||

| Line 39: | Line 39: | ||

===Human Enhancement=== | ===Human Enhancement=== | ||

| − | An issue with using 3D printing involves the topic of human enhancement. While the technology can be used to develop replacements for organs and bones, it is hypothesized that it could also be used to develop features that can enhance humans to go beyond normal capabilities. For instance, is it ethical to replace existing bones with artificial ones that are stronger and more flexible? Should people consider implanting new lungs that oxygenate blood more efficiently? A similar comparison would be the use of performance enhancing drugs in the sports field. Such use is considered cheating, unbalancing the level playing field. An area where 3D bioprinting seems useful would be for military personnels with the idea of enhancing soldiers to be less susceptible to being wounded in battle. Such capabilities in 3D technology may lead to a new kind of arms race and deeper ethical and social issues. | + | An issue with using 3D printing involves the topic of human enhancement. While the technology can be used to develop replacements for organs and bones, it is hypothesized that it could also be used to develop features that can enhance humans to go beyond normal capabilities. For instance, is it ethical to replace existing bones with artificial ones that are stronger and more flexible? Should people consider implanting new lungs that oxygenate blood more efficiently? A similar comparison would be the use of performance enhancing drugs in the sports field. Such use is considered cheating, unbalancing the level playing field. An area where 3D bioprinting seems useful would be for military personnels with the idea of enhancing soldiers to be less susceptible to being wounded in battle. <ref>http://www.abc.net.au/science/articles/2015/02/11/4161675.htm</ref> Such capabilities in 3D technology may lead to a new kind of arms race and deeper ethical and social issues. |

==Continuing Advancements== | ==Continuing Advancements== | ||

Revision as of 05:44, 19 April 2017

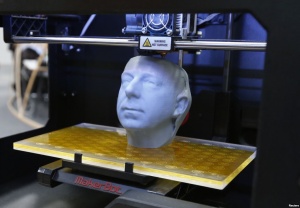

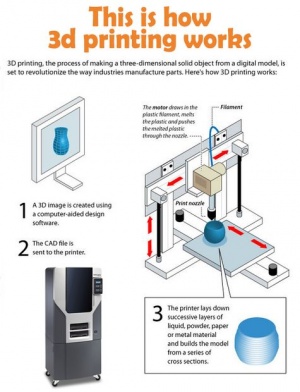

3D printing is the popular term that refers to additive manufacturing (AM) technologies [1]. It is "additive" because it creates a three-dimensional (3D) object by layering materials upon one another, building up the object from scratch rather than removing material as in sculpting and milling.[2] 3D printers possess the ability to take digital model data, created on either a computer-aided design (CAD), computer-aided manufacturing (CAM) program, or from an Additive Manufacturing File (AMF), and transform it into a physical object.[3]

Contents

History

In the 1980s, 3D printing was more commonly referred to as rapid prototyping (RP) technologies.[4] In 1981, Dr. Hideo Kodama of Nagoya Municipal Industrial Research Institute filed for the first patent application for RP technology after inventing two AM construction methods of a 3D plastic model. [5]

In 1986, Charles "Chuck" Hull issued a patent for stereolithography apparatus (SLA). This would later be known as one of the earlier 3D printers. Stereolithography works by exposing a vat of liquid photopolymer, an acrylic-based material, with a UV laser beam. The UV laser beam traces the first layer of an object onto the surface of the liquid, and as that portion is exposed to the UV beam, it hardens into plastic. This process is continued on for many more layers, until the whole object is printed out. [2] As this process had already been founded by Dr. Kodama, Hull's significant role in stereolithography was the design of the STereoLithography (STL) file format that most 3D printing softwares can interpret to begin producing material.

AM processes also include Selective laser sintering (SLS) during which lasers meld layers of powdered material together to produce a solid object, as well as multi-jet modelling (MJM), which also builds up an object by using an inkjet print head to spray a binder solution that will glue together layers of powder.[2]

Usage

In 2005, the RepRap Project was founded in England, and marked the advent of an open-source community working to make 3D printing technologies available for everyone; and so, all designs were released under the GNU General Public License, a free software license. [6] Following the RepRap project came the BfB RapMan 3D printer, the first 3D printer intended for commercial use. [4] Shortly after, MakerBot was founded in 2009. MakerBot sold do-it-yourself styled kits, putting onto the market the possibility for consumers of all types to access and learn this technology to produce their own products and designs. [1]

3D printing can be used to create almost any kind of static product model and prototype - from jewelry to tools to a full-sized house.[7] The automotive industry as well as aviation sector can use 3D printing to make prototypes of vehicle parts. Architects can use 3D printing to create models of their projects. The medical field can utilize 3D printing to produce prosthetics and artificial teeth for their patients, or even replicas of organs to help prepare for surgery. [3] In Sudan, Not Impossible labs created Project Daniel, which worked to print prosthetic arms for Daniel, a teen who had lost his arms as a result of violence. [8] 3D printing can also be used in the engineering field to produce printed electronics, allowing layered circuitry and devices to be printed on flexible material, or in the culinary field to help with food preparation.[3]

3D printing is growing increasingly popular. It is used in several businesses and is moving towards wider personal consumer use in households [9]

Benefits

The technology of 3D printing has revolutionized manufacturing, creating benefits at the industrial, local, and personal level that can't be accomplished with only the traditional methods of manufacturing.

On a personal level, 3D printing grants the ability for mass customization; people can tailor their products to individual needs and constraints in larger numbers at no significant additional process cost. It also eliminates the limitation of complexity for designers and engineers - they are free to let their creativity flow and develop complex products that may even end up being lighter and stronger than past prototypes.[10]

On a local level, 3D printing is acknowledged as a technology that is energy-efficient. It can use up to 90% of standard material, creating little waste, and as a byproduct of producing lighter and stronger materials, it also leaves a smaller carbon footprint than that of manufactured products made from traditional methods. [10]

At an industrial level, 3D printing can reduce financial and time costs for tool production. Products can be manufactured in high volumes while also maintaining uniformity. Products can also be designed in such a way that avoids difficult assembly processes and requirements, decreasing labor and costs there as well. [10]

Ethical Concerns

Intellectual Property Rights

3D printing allows for easy replication and reproducibility. This makes it more difficult to track copyright legislation and protect intellectual property rights.

Misuse

As accessibility to 3D printing technology continues to grow, and consumers hold the freedom to print any design they desire, there are also potential risks. It's possible for an individual to produce a 3D printed firearms, which raises questions regarding gun control and regulation. It grows increasingly difficult to track the online distribution of 3D printable files for firearms, as well as control any production.

Labor Substitution

The benefits of 3D printing on an industrial level also comes with possible consequences. With the speed and ease that the technology provides in manufacturing products in bulk and the ability to reduce labor costs, it could also put millions out of work.

Human Enhancement

An issue with using 3D printing involves the topic of human enhancement. While the technology can be used to develop replacements for organs and bones, it is hypothesized that it could also be used to develop features that can enhance humans to go beyond normal capabilities. For instance, is it ethical to replace existing bones with artificial ones that are stronger and more flexible? Should people consider implanting new lungs that oxygenate blood more efficiently? A similar comparison would be the use of performance enhancing drugs in the sports field. Such use is considered cheating, unbalancing the level playing field. An area where 3D bioprinting seems useful would be for military personnels with the idea of enhancing soldiers to be less susceptible to being wounded in battle. [11] Such capabilities in 3D technology may lead to a new kind of arms race and deeper ethical and social issues.

Continuing Advancements

4D Printing

4D printing incorporates one more dimension: the function of time. The team dubbed "Self-Assembly Lab"[12] at Massachusetts Institute of Technology collaborated with Stratasys, a major 3D printing manufacturer, and the software corporation Autodesk Inc to develop a custom-built and adaptable technology[13].

As an extension of 3D printing, 4D printing aims to skip the step of assembling the printed material ourselves to having them self-assemble as well as autonomously reshape over time. These programmable materials are created with multi-material 3D printing and their responses to changes in environment (mimicked with simple energy inputs of water, heat, and light), as well as geometric code [14].

Skylar Tibbits, a co-director and founder of Self-Assembly Labs, gave a demonstration of 4D printing at a TED Talk in 2013 [15], showing how a single 1D strand dipped in water could proceed to self-fold into the letters 'M I T'.

Concerns

This complex technology introduces many possibilities in engineering. It has already appeared in several businesses, such as sportswear, but soon, the focus may shift from the inorganic world to organic life. Following the same concerns that arise from 3D printing, there is also opportunity for misuse of the programmable matter, and issues in regulation concerning intellectual property law and patenting[16].

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Matias, Elizabeth, and Bharat Rao. "3D Printing: On Its Historical Evolution and the Implications for Business." 2015 Portland International Conference on Management of Engineering and Technology (PICMET) (2015): n. pag. Web. <http://faculty.poly.edu/~brao/3dppicmet.pdf>

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Kumar, Upender, Manoj Pandey, and Tejender Singh Rawat. "Review on 3D Printing Technology and Possible Technological Improvements" <http://www.academicscience.co.in/admin/resources/project/paper/f201505111431317592.docx>

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Hoffman, Tony. "3D Printing: What You Need to Know." PCMAG. PCMAG.COM, 04 Jan. 2016. Web. 21 Mar. 2017. <http://www.pcmag.com/article2/0,2817,2394720,00.asp>

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "History of 3D Printing." 3D Printing Industry. 3D Printing Industry, n.d. Web. 21 Mar. 2017. <https://3dprintingindustry.com/3d-printing-basics-free-beginners-guide/history/>

- ↑ Hideo Kodama, "A Scheme for Three-Dimensional Display by Automatic Fabrication of Three-Dimensional Model," IEICE TRANSACTIONS on Electronics (Japanese Edition), vol.J64-C, No.4, pp.237–241, April 1981

- ↑ "RepRapGPLLicence." RepRapGPLLicence. RepRapWiki, n.d. Web. 21 Mar. 2017. <http://reprap.org/wiki/RepRapGPLLicence>

- ↑ "How Dutch Team Is 3D-printing a Full-sized House." BBC News. BBC, 3 May 2014. Web. 21 Mar. 2017. <http://www.bbc.com/news/technology-27221199>

- ↑ "What We Do." Not Impossible. Not Impossible, LLC, n.d. Web. 21 Mar. 2017. <http://www.notimpossible.com/whatwedo>

- ↑ D'Aveni, Richard (March 2013). "3-D Printing Will Change the World". Harvard Business Review. <https://hbr.org/2013/03/3-d-printing-will-change-the-world>

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 "Benefits & Commercial Value." 3D Printing Industry. 3D Printing Industry, n.d. Web. 21 Mar. 2017. <https://3dprintingindustry.com/3d-printing-basics-free-beginners-guide/benefits-commercial-value/>

- ↑ http://www.abc.net.au/science/articles/2015/02/11/4161675.htm

- ↑ "Self-Assembly Lab." Self-Assembly Lab. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, n.d. Web. 21 Mar. 2017. <http://www.selfassemblylab.net/>

- ↑ "Self-Assembly Lab 4D Printing." Self-Assembly Lab. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, n.d. Web. 21 Mar. 2017. <http://www.selfassemblylab.net/4DPrinting.php>

- ↑ Rieland, Randy. "Forget the 3D Printer: 4D Printing Could Change Everything." Smithsonian.com. Smithsonian Institution, 16 May 2014. Web. 21 Mar. 2017. <http://www.smithsonianmag.com/innovation/Objects-That-Change-Shape-On-Their-Own-180951449/>

- ↑ Tibbits, Skylar. "The Emergence of "4D Printing"." Skylar Tibbits: The Emergence of "4D Printing" | TED Talk | TED.com. TED, Feb. 2013. Web. 21 Mar. 2017. <https://www.ted.com/talks/skylar_tibbits_the_emergence_of_4d_printing>

- ↑ Campbell, Thomas A., Skylar Tibbits, and Banning Garrett. "The Next Wave: 4D Printing." AccessScience (2014): n. pag. Web. <http://www.atlanticcouncil.org/images/publications/The_Next_Wave_4D_Printing_Programming_the_Material_World.pdf>