Ethics of Blockchain

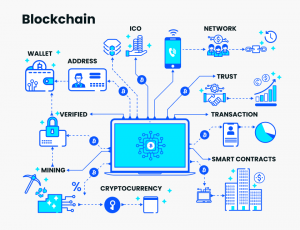

With the growing computational power of computers and the continual expansion and adoption of the digital age, many new technologies have collected much buzz in the 21st century. One such technology that has attracted much attention in the past decade is blockchain. Blockchain, fundamentally, is a distributed database utilizing a distributed ledger. [1] A ledger is a record-keeping system associated with financial accounts. Blockchain implements such a record-keeping system for financial information by recording transactions in an electronic digital format that is distributed. Blockchain being a distributed ledger essentially means that there is no central authority like a bank that manages the data with every user’s account and transaction history. Instead, the distributed ledger of blockchain ensures that this information is stored on every computer that is running blockchain. This is called a decentralized architecture. [1] Blockchain’s technology is secure despite there not being a central authority, and the lack of a central authority is why many people have taken an interest in blockchain.

Although blockchain originally arose as a mechanism to record asset transactions, the fundamental technology of blockchain has many other applications that are being considered and realized in the present day. Some examples include distributed virtual private networks, web3.0, and medical record-keeping. However, a number of ethical considerations also arise as the adoption of blockchain across society increases. Major ethical considerations include its high energy usage and privacy concerns associated with the permanence of data that blockchain records.

History

Origin of Idea

Blockchain was first introduced in 2008 by someone, or some group, under the name of Satoshi Nakamoto. [2] However, origins of a distributed ledger have surfaced as early as 1982 by a University of California, Berkeley, graduate David Chaum. [3] In 1982, David Chaum published a paper for his PhD dissertation titled Computer Systems Established, Maintained and Trusted by Mutually Suspicious Groups, and in which he first outlined the idea for blockchain. [4] In the abstract of the paper, David proposed that “a number of organizations who do not trust one another can build and maintain a highly-secured computer system that they can all trust (if they agree on a workable design).” [4] However, the adoption of blockchain did not start until 2008.

Idea Development and Adoption

In 2008, someone by the name of Satoshi Nakamoto published a paper online titled "Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System". [3] In the paper, he described in detail the structure of such a blockchain system. [3] Satoshi Nakamoto solved something that previously remained a flaw for blockchain technologies, that of double spending. [3] Double spending is when users spend the same digital currency twice, and Satoshi Nakamoto solved this problem through his creation of a secure verification system. [3] This improvement allowed for the adoption of blockchain, and, most notably, Bitcoin, which was the first largely adopted cryptocurrency.

Implementation

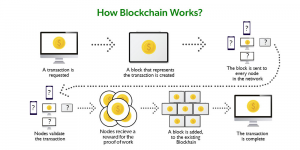

The implementation of blockchain can be broken down into “block”, and “chain”.

Block

Blockchain is a distributed ledger, which means that it doesn’t have a central authority maintaining all the information. Instead, information is stored in a collection of digital blocks. Each block stores information such as an ID, a timestamp, a cryptographic hash of the previous block, and some actual transactions such as “Alice sent 1 bitcoin to Bob”. A block may store a few transactions, but the collection of all blocks stores all of the transactions in the database. [5]

Chain

The collection of blocks, altogether, form digital chain(s), hence the name “blockchain”. Each block connects to a previous block through a cryptographic hash. [1] In aggregate, a chain consisting of blocks of information are formed. This chain is the record-book for all transactions that have taken place. Because there is always a way to connect to the previous block in the chain, it is possible to traverse all the way back to the first block ever, known as the “genesis block”. [5] This means that once a transaction is finalized as a block on the chain, the information is there forever and can never be deleted. Thus, users are always able to collectively agree on who has which assets because all the transactions are recorded openly. This is the peer-to-peer protocol that allows users to collectively build a log of every transaction ever. [5]

Proof of Work

The proof of work mechanism is what gives blockchain its secure properties. Since there is no central authority, there needs to be a secure mechanism to verify the legitimacy of any transaction. If anyone were allowed to add blocks to the chain, any user “Tom” could simply just add a block with information such as “Alice sent 100 bitcoins to Tom” and “Bob sent 100 bitcoins to Tom”. [5] Blockchain’s architecture counteracts this by requiring a “proof-of-work” to verify new transactions. [6] When a new block is introduced as a candidate to be added to the chain, other blockchain users compete against each other to mine this new block by guessing random numbers that results in a hash starting with a bunch of 0’s. [5] Because hashing is a one-way algorithm, there is no way to figure out a correct number algorithmically, and it can only be guessed correctly after exhausting many many tries. [6] Upon a correct guess, other users verify that this block’s transactions are legitimate. This prevents someone from creating fake transactions unless they control the majority of the users of blockchain, which would require billions of dollars. [5]

Applications

There are a number of use cases of blockchain, but all of them revolve around the idea of decentralization. Cryptocurrency, decentralized VPNs, Web3.0, and an electronic record-keeping system for medical data are some technologies that can be implemented with a blockchain. [7]

Cryptocurrency

Cryptocurrency, or crypto, is a major use case for blockchain. Cryptocurrencies are digital assets that people can invest in, buy, sell, and mine. Most cryptocurrencies are implemented with blockchain. Some notable cryptocurrencies used today include Bitcoin (BTC), created in 2009 by Satoshi Nakamoto with a present-day market cap of $440.5 billion, Ethereum (ETH), a present-day market cap of $199 billion, and Tether (USDT), a cryptocurrency that is pegged to the value of $1 USD. [8] As a frame of reference, one Bitcoin costs about $23,095 today. [8]

Decentralized VPNs

Decentralized virtual private networks is another application of blockchain. A normal virtual private network (VPN) allows users of the virtual private network additional privacy and security when browsing the web by encrypting communications and sending them through a secure tunnel managed by a virtual private network service provider. [9] However, there is still a company that manages the secure tunnel and maintains central control over it. However, with decentralized VPNs, there is no single entity that maintains centralized control. Instead, the secure tunnel is created by a set of users who offer their unused network traffic. [9] In this way, people who use decentralized VPNs are both users as well as service providers. They can both use network traffic offered by others and become a node in this network that allows others to use. [9]

Web3.0

Web3.0 is another application that blockchain technology can provide. Web3.0 is a version of the web that is different from the previous ways in which the web worked. The first web pages were static web pages. [10] A static website is a website where users can only read information but cannot modify, edit, or change anything that allows others to see their changes. The content on the page is the same for each user who visits that page and will not change. [10] This is not very useful because it does not allow any interactivity.

Dynamic sites then arose which is the way the web works right now. Users can edit webpages and others can see their changes. This is known as Web2.0. [10]

Web3.0 represents an effort to decentralize the architecture of the web. Prior to web3.0, the web operated on entities such as google.com, chrome, Facebook, Youtube, and others. Supporters of web3.0 believe that shifting the control from big tech companies into the masses will enhance the privacy, transparency, and ownership of individual users and their data. [10]

Voting

While a traditional voting system might consist of ballot papers or a central database to store electronic votes, voting can be implemented with blockchain as well. Supporters of the blockchain technology in voting and elections believe that the transparent and decentralized nature of the blockchain system can eliminate voter fraud since all votes are transparent and authenticated. [11]

Healthcare

Another application of blockchain is medical record-keeping. Blockchain can store the health records of patients in a single secure system. [11] While traditional medical records might be scattered across databases, blockchain can provide a decentralized system for storing all patients data in a single system. This can increase the efficiency in which doctors look up patient data and increase data integrity. [12] Furthermore, it can eliminate the time it takes for a patient's medical information updated in one database to appear in another database, since it is all stored in one place, and thus any patient's data will always be up to date. [12] Blockchain in healthcare can also give patients more control over their medical health records. Because of the cryptographic hash properties in which blockchain is implemented upon, patients can prevent others from seeing their sensitive medical data. [12]

Ethical Considerations

Energy Usage and Environmental Impacts

There are a number of ethical considerations associated with blockchain. One of the main ethical issues involves the enormous amounts of environmental issues that blockchain causes. When a block is made public in a cryptocurrency system, other users compete against each other to mine this block by guessing random numbers. This is made intentionally a difficult task to accomplish. Anyone can mine cryptocurrency, but it will only be profitable to the user if the reward obtained is greater than the cost of expending the electricity power to do so. [13] There are hardware units specifically designed to be highly efficient at mining cryptocurrency. For example, certain "application-specific integrated circuits" (ASICS) are customized to be Bitcoin mining machines. [13] Certain editions can generate around 100 trillion hashes per second. [13] The electricity generation needed to power these processes results in high levels CO2 emissions. It is estimated that between mid-2021 and 2022, cryptocurrency mining contributed to 27.4 million tons of excess carbon dioxide emissions. [14] To put it into perspective on a smaller scale, a single Bitcoin transaction costs about $176 of power. That’s enough to power an average U.S. household’s electricity usage for 6 weeks. [15] Furthermore, there are cryptocurrency mining facilities (or cryptocurrency mining farms) that are facilities built only for the purpose of setting up many computers to mine cryptocurrencies for 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. [16] These mining farms are located across the globe. In addition to the computers inside these facilities, fans and air conditioning need to be set up as well next to the computers to help cool down the computers as they generate lots of heat. [16] China was once the major location of mining facilities, before they banned all cryptocurrency mining in 2021. [16] Major countries in 2022 that contain large mining facilities include Russia, the U.S., Malaysia, Iran, Kazakhstan, Canada, Germany, and Ireland. [16]

Noise Pollution

Along with the energy output of mining cryptocurrency, mining facilities also generate a lot of noise. The high noise levels come from the huge fans that must keep the computers that mine cool. The noise level is a source of complaint and lawsuits among residents who live near these cryptocurrency mining facilities. [17] America's lack of comprehensive noise pollution standards have resulted in people having to move homes due to the high levels of noise caused by living close to these cryptocurrency mining facilities. [17]

Lack of Privacy

In the sector of healthcare, blockchain poses ethical questions to be grappled with as well. It is impossible to remove any block on a blockchain. Therefore, once information is added to the blockchain, there is no way to discard it. [18] Electronic health records and medical information can be stored in a blockchain as well, instead of a distributed database. [19] Some users will prefer this approach because it gives them more control over their data. [19] However, any information that is entered into the blockchain will remain there forever, as there is no way to remove any blocks from the chain. Thus, there is no way for individuals to request that a health record or their medical data be deleted. [18]

Lack of a central authority

The fundamental structure upon which the blockchain technology is built of not having a central authority can also introduce ethical considerations as well. Because blockchain doesn't have a central authority, there is a lack of a third-party safeguard. [19] A possible problem that could occur is that Bitcoin can lose all its value in a day if people stop valuing it. If this happens, investors of Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies could lose all the money they've invested in these cryptocurrencies in a day. Unlike the U.S. dollar, which is backed by the government, a cryptocurrency is not backed by any physical entity. Instead, it only works as long as people trust the system. [19] Issues could arise when the value of cryptocurrencies drop rapidly. For example, in the recent economic downturn of 2022, Bitcoin lost over 60% of its value. [20] Other cryptocurrencies lost a lot of value in a short period of time as well. For example, Terra lost over 99.99% of its value, Solano lost 93% of its value, AMP lost 93% of its value, Cardano lost 80% of this value, Ether lost 67% of its value, and Dogecoin lost around 55% of its value in 2022 only. [20] The highly volatile properties of cryptocurrencies mean that people could lose a fortune in a very short amount of time, and it is an ethical topic of consideration regarding the damage that such a downturn could cause to people and communities in large.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 SoFi. (2022, November 21). Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT) vs. Blockchain. SoFi. Retrieved January 27, 2023, from https://www.sofi.com/learn/content/dlt-vs-blockchain/

- ↑ History of blockchain. ICAEW. (n.d.). Retrieved January 27, 2023, from https://www.icaew.com/technical/technology/blockchain-and-cryptoassets/blockchain-articles/what-is-blockchain/history

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 A brief history of blockchain technology everyone should read. Kriptomat. (2022, March 17). Retrieved January 27, 2023, from https://kriptomat.io/blockchain/history-of-blockchain/

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Publications. chaum.com. (2022, November 9). Retrieved January 27, 2023, from https://chaum.com/publications/

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Kloosterman, John. "Blockchain." Web Systems, 12 April 2022, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Lecture

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 https://www.forbes.com/advisor/investing/cryptocurrency/proof-of-work/

- ↑ SoFi. (2022, December 1). 9 blockchain uses and applications in 2022. SoFi. Retrieved January 27, 2023, from https://www.sofi.com/learn/content/blockchain-applications/

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Royal, J. (n.d.). 12 most popular types of cryptocurrency. Bankrate. Retrieved January 27, 2023, from https://www.bankrate.com/investing/types-of-cryptocurrency/

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 What are decentralized vpns? possible benefits and risks - atlas VPN. atlasVPN. (n.d.). Retrieved January 27, 2023, from https://atlasvpn.com/blog/what-are-decentralized-vpns-possible-benefits-and-risks

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Ashmore, D. (2023, January 9). A brief history of web 3.0. Forbes. Retrieved January 27, 2023, from https://www.forbes.com/advisor/investing/cryptocurrency/what-is-web-3-0/

- ↑ 11.0 11.1

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Xiao, Y., Xu, B., Jiang, W., & Wu, Y. (2021, January 22). The healthchain blockchain for Electronic Health Records: Development Study. Journal of medical Internet research. Retrieved February 10, 2023, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7864769/

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Whittaker, M. (2023, January 30). How does bitcoin mining work? Forbes. Retrieved February 10, 2023, from https://www.forbes.com/advisor/investing/cryptocurrency/bitcoin-mining/

- ↑ The environmental impacts of cryptomining. Earthjustice. (2022, September 23). Retrieved January 27, 2023, from https://earthjustice.org/features/cryptocurrency-mining-environmental-impacts#:~:text=Top%2Ddown%20estimates%20of%20the,in%20the%20U.S.%20in%202021

- ↑ Calhoun, G. (2022, October 27). The ethics of crypto: Good intentions and bad actors. Forbes. Retrieved January 27, 2023, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/georgecalhoun/2022/10/11/the-ethics-of-crypto-sorting-out-good-intentions-and-bad-actors/?sh=36e9e7815c49

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Strachan, R. (2022, June 22). Where are the key bitcoin mining hotspots and what is the industry's future? Investment Monitor. Retrieved February 10, 2023, from https://www.investmentmonitor.ai/finance/bitcoin-mining-hotspots-energy-countries/

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Kevin Williams, R. T. (2022, August 31). A neighborhood's cryptocurrency mine: 'like a jet that never leaves'. The Washington Post. Retrieved February 10, 2023, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/interactive/2022/cryptocurrency-mine-noise-homes-nc/

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Leonid. (2022, April 28). Blockchain in Healthcare: Ethical Considerations. CIFS Health. Retrieved January 27, 2023, from https://cifs.health/backgrounds/blockchain-in-healthcare-ethical-considerations/

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 Why Blockchain's ethical stakes are so high. Harvard Business Review. (2023, January 10). Retrieved February 10, 2023, from https://hbr.org/2022/05/why-blockchains-ethical-stakes-are-so-high

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 DeVon, C. (2022, December 23). Bitcoin lost over 60% of its value in 2022-here's how much 6 other popular cryptocurrencies lost. CNBC. Retrieved February 10, 2023, from https://www.cnbc.com/2022/12/23/bitcoin-lost-over-60-percent-of-its-value-in-2022.html#:~:text=Bitcoin%20lost%20over%2060%25%20of%20its%20value%20in%202022