Difference between revisions of "Jeremy Bentham"

(→Personal Life) |

(→Personal Life) |

||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

From an early age, both brothers were found to be very bright, but Jeremy in particular appeared to possess strong mental abilities. His father's friends would refer to Jeremy as a "Philosopher" starting at the young age of 5. He spent much of his time at his two grandmothers' rural homes. Jeremy learned Latin grammar at the age of three and the Greek alphabet as a young child and also picked up the violin before age 7. Around this time, he also quickly learned French from a tutor and eventually wrote many of his works in the language. Jeremy's parents played a large role in his studies, particularly Jeremy's father who found Jeremy's intelligence dumbfounding believing the Jeremy would go on to be the Lord chancellor of Britain. <ref name = "UCL"> UCL Bentham Project, web.archive.org/web/20070101105009/http://www.ucl.ac.uk/Bentham-Project/info/jb.htm.</ref>. <br/> | From an early age, both brothers were found to be very bright, but Jeremy in particular appeared to possess strong mental abilities. His father's friends would refer to Jeremy as a "Philosopher" starting at the young age of 5. He spent much of his time at his two grandmothers' rural homes. Jeremy learned Latin grammar at the age of three and the Greek alphabet as a young child and also picked up the violin before age 7. Around this time, he also quickly learned French from a tutor and eventually wrote many of his works in the language. Jeremy's parents played a large role in his studies, particularly Jeremy's father who found Jeremy's intelligence dumbfounding believing the Jeremy would go on to be the Lord chancellor of Britain. <ref name = "UCL"> UCL Bentham Project, web.archive.org/web/20070101105009/http://www.ucl.ac.uk/Bentham-Project/info/jb.htm.</ref>. <br/> | ||

| − | Pushing Jeremy to develop his intellectual abilities, in 1755, Jeremy's parents sent him to Westminster boarding school, where he earned a reputation for his ability to write Latin and Greek verse. In spite of the academic achievements he made at Westminster, Jeremy found his experience there to be unpleasant. Jeremy studied law at The Queen's College, Oxford; although Jeremy never became a practicing lawyer, we wrote many works critiquing law and suggesting improvement.<ref name = "UCL"/> Bentham would often spend eight to twelve hours a day writing on matters of legal reform, however much of the work he wrote remained unpublished by the end of his life. <ref name="Atkinson"/> His mother died in 1769, when Jeremy was 11 years old and the death of Jeremy's mother is said to be one of the reasons behind Samuel and Jeremy's close bond which was an important aspect | + | Pushing Jeremy to develop his intellectual abilities, in 1755, Jeremy's parents sent him to Westminster boarding school, where he earned a reputation for his ability to write Latin and Greek verse. In spite of the academic achievements he made at Westminster, Jeremy found his experience there to be unpleasant. Jeremy studied law at The Queen's College, Oxford; although Jeremy never became a practicing lawyer, we wrote many works critiquing law and suggesting improvement.<ref name = "UCL"/> Bentham would often spend eight to twelve hours a day writing on matters of legal reform, however much of the work he wrote remained unpublished by the end of his life. <ref name="Atkinson"/> His mother died in 1769, when Jeremy was 11 years old and the death of Jeremy's mother is said to be one of the reasons behind Samuel and Jeremy's close bond which was an important aspect throughout his life.<ref name="Atkinson"/><ref name = "Pease"/> |

| − | + | Samuel, like Jeremy, was a bright individual. He became a naval architect by landing an apprenticeship at age fourteen. His navel architect job allowed him to visit Russia where he found a new range of opportunities for invention, from which he became an inventor of mechanical contrivances He stayed in Russia for a time before returning back to London.<ref name = "Pease"/> He also became a knight. He died in 1831 just a year before his brother.<ref name="Atkinson"/> Jeremey never married, and died in 1832 without kids. | |

Jeremy also played a part in responding to the Americans Declaration of Independence in 1776. He wrote an essay, "Short Review of the Declaration" , which voiced an opinion against the new America's politics. <ref>Lind., Bentham., "An Answer to the Declaration of the American Congress" 1776., https://books.google.com/books?id=iHNbAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA3#v=onepage&q&f=false</ref> | Jeremy also played a part in responding to the Americans Declaration of Independence in 1776. He wrote an essay, "Short Review of the Declaration" , which voiced an opinion against the new America's politics. <ref>Lind., Bentham., "An Answer to the Declaration of the American Congress" 1776., https://books.google.com/books?id=iHNbAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA3#v=onepage&q&f=false</ref> | ||

Revision as of 22:14, 13 April 2019

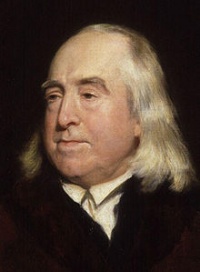

Jeremy Bentham, a British philosopher, was born February 15th, 1748 in London, England and died June 6th, 1832 also in London.[1] He contributed many ideas to various fields including philosophy, economics, public policy, government, and law. Bentham was considered a consequentialist and utilitarian, and is widely regarded as the founder of modern utilitarianism. In his contemplation of right and wrong, he explored the concepts of utility and the greatest happiness principle. Although not the first to create those ideas, Bentham's work has continued to influence thought in these areas since the nineteenth century.[2]

Contents

Personal Life

Jeremy Bentham was born to Jeremiah Bentham, a lawyer in an established London family, and Alicia Grove, the daughter of a wealthy Andover tradesman. Bentham's parents marriage took in 1744, with much disapproval from Jeremiah's parents. It was the expectation that Jeremiah marry a family acquaintance but Jeremiah departed from their wishes and married Alicia Grove. In 1748, four years after Jeremiah and Alicia married, Jeremy named after his father, was born on February 15th in Red Lion Street, Houndsditch, London. In 1757, nine years after Jeremy's birth, Jeremy's brother Samuel was born on January 11th.[3]Samuel was the only surviving sibling of the five siblings which Jeremy had. The other siblings which were born to Jeremy's parents died prematurely.[4]

From an early age, both brothers were found to be very bright, but Jeremy in particular appeared to possess strong mental abilities. His father's friends would refer to Jeremy as a "Philosopher" starting at the young age of 5. He spent much of his time at his two grandmothers' rural homes. Jeremy learned Latin grammar at the age of three and the Greek alphabet as a young child and also picked up the violin before age 7. Around this time, he also quickly learned French from a tutor and eventually wrote many of his works in the language. Jeremy's parents played a large role in his studies, particularly Jeremy's father who found Jeremy's intelligence dumbfounding believing the Jeremy would go on to be the Lord chancellor of Britain. [5].

Pushing Jeremy to develop his intellectual abilities, in 1755, Jeremy's parents sent him to Westminster boarding school, where he earned a reputation for his ability to write Latin and Greek verse. In spite of the academic achievements he made at Westminster, Jeremy found his experience there to be unpleasant. Jeremy studied law at The Queen's College, Oxford; although Jeremy never became a practicing lawyer, we wrote many works critiquing law and suggesting improvement.[5] Bentham would often spend eight to twelve hours a day writing on matters of legal reform, however much of the work he wrote remained unpublished by the end of his life. [3] His mother died in 1769, when Jeremy was 11 years old and the death of Jeremy's mother is said to be one of the reasons behind Samuel and Jeremy's close bond which was an important aspect throughout his life.[3][4]

Samuel, like Jeremy, was a bright individual. He became a naval architect by landing an apprenticeship at age fourteen. His navel architect job allowed him to visit Russia where he found a new range of opportunities for invention, from which he became an inventor of mechanical contrivances He stayed in Russia for a time before returning back to London.[4] He also became a knight. He died in 1831 just a year before his brother.[3] Jeremey never married, and died in 1832 without kids.

Jeremy also played a part in responding to the Americans Declaration of Independence in 1776. He wrote an essay, "Short Review of the Declaration" , which voiced an opinion against the new America's politics. [6]

Work

Bentham began his career as a legal theorist in 1776 by anonymously publishing "A Fragment on Government".[7] However, his best known work was his book "An Introduction toe the Principles of Morals and Legislation," published in 1789. The book contains important statements that lay the foundations of utilitarian philosophy and pioneer the study of crime and punishment, both of which remain at the heart of contemporary debates in moral and political philosophy, economics, and legal theory.[2] Bentham also wrote three important French volumes of Traités de législation civil et pénale in 1802, two of which were later translated to English and published in "The Theory of Legislation" by the American utilitarian Richard Hildreth in 1840. This text went on to become the center of utilitarian studies in the English speaking world through to the mid-twentieth century.[8]

When Bentham died on June 6, 1832, he left a large estate that would eventually be used to finance the creation of University College, London as well thousands of unfinished manuscripts that he had intended to be published. [9]

Utilitarianism

Much of Bentham's philosophical views are shaped as a result of a deep-seated distrust of those in positions of power.[7] For Bentham, a right action is one that produces good, or prevents evil. He also believed in psychological hedonism, that the nature of mankind revolves around the experiences of pain and pleasure. The development of his psychological theory was rooted in uncovering the telos of human action. Bentham asserted "the greatest happiness principle" or "the principle of utility" 'assumes' the truth of ethical hedonism and constructs a moral 'system' on its 'foundation' with the help of 'reason.'[9] The moral agent, then has an obligation to maximize overall human happiness. According to his principles, any act which does not maximize human happiness is considered morally wrong. For government, Bentham believed it could most effectively maximize human happiness by concentrating on the community it represents, by making happiness of their citizens a primary concern.

Bentham also acknowledged the importance of context. He thought moral agents should promote the interest of others, given the circumstances they may find themselves in. He also recognized that violation of moral rules could have desirable consequences in some cases. If the benefits of violating a moral rule can be shown, then the act is warranted by the principle of utility.[9] In spite of the nuanced view he chose to take on, Benthan was grouped into a collection of intellectuals referred to as "the philosophic radicals" by Elie Halévy in 1904. John Stuart Mill and Hebert Spencer were considered precursors to Bentham and were grouped into this family of philosophers as well. [7]

Privacy and Information Ethics

Jeremy Bentham gave significant attention to his thoughts on individual privacy. He strongly believed that law was an invasion of privacy and that it should be justified on the ground of necessary utility. This idea also influenced the thinking of John Stuart Mill, who was contrastingly supportive of publicity.[10]

Transparency

Bentham also believed transparency was of moral value because it held those in power accountable for their actions. This is the often how journalism is viewed in modern society. The use of 21st century technologies to challenge institutions by allowing dissenting opinions to be heard and disseminated is a deployment of Bentham's "publicity principle" and is exemplified in many modern movements, such as the "#MeToo" movement. [11]

Although Bentham believed in transparency, he also held nuanced views about "too much" transparency and what kind of influence that might have on voters' decisions in elections. The best way to qualify Bentham's argument on this issue is to use his own words, "The system of secresy has therefore a useful tendency in those circumstances in which publicity exposes the voter to the influence of a particular interest opposed to the public interest. Secresy is therefore in general suitable in elections." [12] These ideas also influenced political theorist, Jon Elster, who held a similar view on the pros and cons for privacy and publicity.[12]

Surveillance

Bentham considered both surveillance and transparency to be useful in generating understanding and improvements for people's lives. This was exemplified in his creation of a prison design he called Panopticon, which allowed any person to safely enter it and be able to see every prisoner in it at once. This had the advantage of allowing the public to see how prisoner’s were being treated, and made prison guards more accountable.[13] In addition, the idea for courtrooms to allow third parties to view and critique the proceedings is an idea formulated by Jeremy Bentham, and has been influential in shaping the adjudication policies of republics around the world. [11]

While both of these instances are examples of concrete surveillance, surveillance in modern society has become more "liquified".[14] The panopticon served to make prisoners and guards more conscientious of their surroundings and actions; likewise, citizens of the modern world are aware of surveillance methods such as cameras, biometric checks, and identification documents that serve to mitigate unwarranted behavior. The ethical implications of both forms of surveillance have been frequently debated, and concerns have increased since the digitalization of surveillance and personal information. A main concern is that as surveillance becomes more omnipresent, transparency will increase among citizens and decrease in governments and organizations. This would create a societal shift in power, secrecy, and knowledge. Scholars have considered the liquefaction of surveillance, characterized by its ubiquity and adaptability, a move towards a more post-panoptical society.[14]

See Also

References

- ↑ "Duignan, Brian, and John P. Plamenatz. “Jeremy Bentham : British Philosopher and Economist.” Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11 Feb. 2019, www.britannica.com.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 " Bentham, Jeremy. The Collected Works of Jeremy Bentham : An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation. Edited by J. Burns et al., Clarendon Press, 1996."

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 "Atkinson, Charles M. Jeremy Bentham : His Life and Work. Methuen & Co., 1905."

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Pease-Watkin, C. ‘Jeremy and Samuel Bentham – The Private and the Public.’ Journal of Bentham Studies, 2002, 5(1): 2, pp. 1–27. DOI: https://doi.org/10.14324/111.2045-757X.017.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 UCL Bentham Project, web.archive.org/web/20070101105009/http://www.ucl.ac.uk/Bentham-Project/info/jb.htm.

- ↑ Lind., Bentham., "An Answer to the Declaration of the American Congress" 1776., https://books.google.com/books?id=iHNbAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA3#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 "Crimmins, James E., "Jeremy Bentham", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2019 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2019/entries/bentham/>."

- ↑ "needciation

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 "Bentham, Jeremy. Critical Assessments. Routledge, 1993."

- ↑ "Barendt, Eric M. “Why Privacy Is Valuable.” Privacy, edited by Eric Barendt, Dartmouth Publishing Company and Ashgate Publishing, 2001, p. 3–9."

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Resnik, Judith, The Functions of Publicity and of Privatization in Courts and their Replacements (from Jeremy Bentham to #MeToo and Google Spain) (October 22, 2018). Open Justice: The Role of Courts in a Democratic Society, Burkhard Hess and Ana Koprivica (editors), Nomos, 2019; Yale Law School, Public Law Research Paper No. 659. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3271284"

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "Gosseries, Axel and Parr, Tom, "Publicity", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2018 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2018/entries/publicity/>.

- ↑ " Benjamin J. Goold (2002) Privacy rights and public spaces: CCTV and the problem of the “unobservable observer”, Criminal Justice Ethics, 21:1, 21-27, DOI: 10.1080/0731129X.2002.9992113"

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Lyon, D. & Buaman, Z., "Liquid Surveillance", 2013, p. 1-17