Difference between revisions of "Black Twitter"

(→Ethical Component) |

(→Racialized Hashtags) |

||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

== Racialized Hashtags == | == Racialized Hashtags == | ||

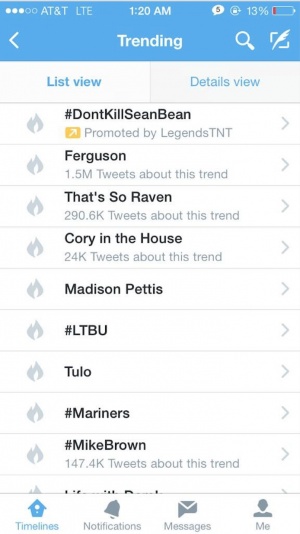

| − | [[File: | + | [[File:Trendings.jpeg|thumbnail|Example of Black Twitter Content Reaching Twitter Trends]] |

===Background=== | ===Background=== | ||

Hashtags in Twitter are pieces of metadata used to classify and group user-generated content into themes. When used appropriately, hashtags create curated content that can be followed and easily searchable. Much like regular hashtags, racialized hashtags help curate content, however, specifically group content relating to race and culture. A critical part to Black Twitter’s success is the use of racialized hashtags which helps facilitate raced based conversations across Twitter’s global audience<ref>Brock, A. (2012). From the Blackhand Side: Twitter as a Cultural Conversation. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 56(4), 529-549. doi:10.1080/08838151.2012.732147</ref>. These hashtags are specific to the Black community by mimicking the vernacular of their community and it's content ranges from humorous memes and commentary to social justice issues the community cares about<ref>Sharma, S. (2013). Black Twitter? Racial Hashtags, Networks and Contagion. New Formations, 78(78), 46-64. doi:10.3898/newf.78.02.2013</ref>. Examples of popular racialized hashtags include, but are not limited to the following: #OnlyInTheGhetto, #BlackGirlMagic, #HandsUpDontShoot, and #LivingWhileBlack. With these racialized hashtags being a primary identifier of Black Twitter tweets, they are not all encompassing of all Black individuals on Twitter and reinforce stereotypes of the Black community. Not all racialized hashtags should not be taken seriously, and not all portray an accurate representation of all individuals who identify with the Black community. Racial bias comes into play when users associate racialized hashtags with the Black community as a whole<ref>Ibid</ref>. Oliver L. Haimson and Anna Lauren Hoffmann say that marginalized and culturally stigmatized communities struggle the most with their online identity<ref>Haimson, O. L., & Hoffmann, A. L. (2016). Constructing and enforcing "authentic" identity online: Facebook, real names, and non-normative identities. First Monday, 21(6). doi:10.5210/fm.v21i6.6791</ref> as racialized hashtags become an issue when their meaning feeds into a stigma and becomes part of a generalization. | Hashtags in Twitter are pieces of metadata used to classify and group user-generated content into themes. When used appropriately, hashtags create curated content that can be followed and easily searchable. Much like regular hashtags, racialized hashtags help curate content, however, specifically group content relating to race and culture. A critical part to Black Twitter’s success is the use of racialized hashtags which helps facilitate raced based conversations across Twitter’s global audience<ref>Brock, A. (2012). From the Blackhand Side: Twitter as a Cultural Conversation. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 56(4), 529-549. doi:10.1080/08838151.2012.732147</ref>. These hashtags are specific to the Black community by mimicking the vernacular of their community and it's content ranges from humorous memes and commentary to social justice issues the community cares about<ref>Sharma, S. (2013). Black Twitter? Racial Hashtags, Networks and Contagion. New Formations, 78(78), 46-64. doi:10.3898/newf.78.02.2013</ref>. Examples of popular racialized hashtags include, but are not limited to the following: #OnlyInTheGhetto, #BlackGirlMagic, #HandsUpDontShoot, and #LivingWhileBlack. With these racialized hashtags being a primary identifier of Black Twitter tweets, they are not all encompassing of all Black individuals on Twitter and reinforce stereotypes of the Black community. Not all racialized hashtags should not be taken seriously, and not all portray an accurate representation of all individuals who identify with the Black community. Racial bias comes into play when users associate racialized hashtags with the Black community as a whole<ref>Ibid</ref>. Oliver L. Haimson and Anna Lauren Hoffmann say that marginalized and culturally stigmatized communities struggle the most with their online identity<ref>Haimson, O. L., & Hoffmann, A. L. (2016). Constructing and enforcing "authentic" identity online: Facebook, real names, and non-normative identities. First Monday, 21(6). doi:10.5210/fm.v21i6.6791</ref> as racialized hashtags become an issue when their meaning feeds into a stigma and becomes part of a generalization. | ||

Revision as of 18:40, 29 March 2019

Black Twitter, is an online community that leverages social platform Twitter to come together to discuss and share race-related messages with one another. Twitter, which was created by Jack Dorsey, Evan Williams, and Biz Stone allows users to “tweet” small short messages and include the use of hashtags to classify and group content together [1]. Black Twitter has leveraged Twitter’s hashtag functionality to create hashtags specific to their community. Users are able to create community specific content to construct a dialogue exploring the cultural nuances of Black identity. Black Twitter is the most active when race-related issues occur and there is little to no public reaction to the event. A prominent example is the fatal killing of Mike Brown in Ferguson, Missouri which spiked national online activism through the Black community on Twitter aided by the use of hashtags like #HandsUpDontShoot, #BlackLivesMatter, and #JusticeForMikeBrown. Black Twitter also comes together to watch and discuss TV shows as well as partake in lighthearted discussions through community specific memes and racialized hashtags.

Contents

History

The term “Black Twitter”, stemmed from Chiore Sicha’s article “What were Black People Taking About on Twitter Last Night” in 2009. In his article, Sicha identifies the coming of Black Twitter through its use of race-related hashtags and Twitter's capability to expand beyond one's own personal network -- something Sicha points out Facebook and Myspace could not accomplish [2]. Through hashtags and viral content, Black Twitter not only attracts the attention of individuals in the community but also users who may not associate with Black Twitter.

Racialized Hashtags

Background

Hashtags in Twitter are pieces of metadata used to classify and group user-generated content into themes. When used appropriately, hashtags create curated content that can be followed and easily searchable. Much like regular hashtags, racialized hashtags help curate content, however, specifically group content relating to race and culture. A critical part to Black Twitter’s success is the use of racialized hashtags which helps facilitate raced based conversations across Twitter’s global audience[3]. These hashtags are specific to the Black community by mimicking the vernacular of their community and it's content ranges from humorous memes and commentary to social justice issues the community cares about[4]. Examples of popular racialized hashtags include, but are not limited to the following: #OnlyInTheGhetto, #BlackGirlMagic, #HandsUpDontShoot, and #LivingWhileBlack. With these racialized hashtags being a primary identifier of Black Twitter tweets, they are not all encompassing of all Black individuals on Twitter and reinforce stereotypes of the Black community. Not all racialized hashtags should not be taken seriously, and not all portray an accurate representation of all individuals who identify with the Black community. Racial bias comes into play when users associate racialized hashtags with the Black community as a whole[5]. Oliver L. Haimson and Anna Lauren Hoffmann say that marginalized and culturally stigmatized communities struggle the most with their online identity[6] as racialized hashtags become an issue when their meaning feeds into a stigma and becomes part of a generalization.

#AtABlackPersonFuneral

Racialized hashtags can take on a presence similar to a meme, where aspects of culture are imitated digitally. The hashtag #atablackpersonfuneral was followed by “The other gang members stand beside the casket planning the revenge”, “you don't have to cremate them if they ass already ashy.”, or “... there is always at least one white person who feels completely out of place”[7]. Tweets tagged with #atablackpersonfuneral are meant to be comical but reinforce stereotypes individuals in the Black community try to disassociate with.

#PaulasBestDishes

Following racist comments made by Paula Deen, a white American cooking show host, Black Twitter exploded with the use of the hashtag #PaulasBestDishes which served as a dark parody playing off Paula’s role as a chef. Examples of tweets tagged with #PaulasBestDishes include “Massa-roni and cheese”, “White Devil’s Food Cake, “Back of the Bus Biscuits”, “Klu Klux Klandike Bars”, “Lynchables”, jab at Deen’s Southern heritage and speciality[8]. #PaulasBestDishes is an example of hashtag activism with memetic underlays to the tweet created. Moor’s law states that “As technological revolutions increase their social impact, ethical problems increase.”[9] The impact Black Twitter has can be seen in the deterioration of Paula Deen’s career and the immediate cancellation of two cooking shows she hosted following the rise of #PaulasBestDishes on Twitter[10].

#Ferguson

Following the shooting of 18-year-old Michael Brown by police officer Darren Wilson on August 9th, 2014 in Ferguson, Missouri, Black Twitter posted photos and commentary on Michael Brown’s death. Photos quickly went viral, and ‘#Ferguson’ had populated over 8 million times on Twitter in the span of one month[11]. Hashtags related to Ferguson such as #HandsUpDontShoot, #MikeBrown, and #STL also populated Twitter feeds and Trending Topics. Through the use of hashtags, Black Twitter was able to share information not publicized by mainstream media sources and spark reactions throughout the United States. The virality of Ferguson content can be attributed to the raw and disturbing footage of Mike Brown's body on the ground as it elicits both feelings of indignation and terror.

Ethical Component

Generalization

Part of what makes racialized hashtags successful is the wide range audience that finds the content relatable and humorous. Black Twitter’s racialized hashtags serve as a connecting piece for a community of individuals that have felt oppressed and marginalized throughout history. Racialized hashtags walk a fine line of truth as they create relatable content, but fail to accurately represent all Black individuals. Using Copp’s understanding of self-identity, an individual’s self-esteem is linked to a variety of characteristics and traits that belong to their identity group. Whether or not the individual believes these properties are applicable to themselves is irrelevant as these properties are still associated with them [12]. An example of this would be Black Twitter users circulating tweets about growing up in the ghetto. While not all Black Twitter users grew up in a ghetto, these tweets are still applied and associated to all Black individuals. This raises ethical concerns of generalizations, especially in the Black community who has a history of struggling to break free from negative stereotypes in attempts to reshape how society views them. The use of generalizations aids in the process of “othering”, where discrimination occurs through classifications of characteristics and differences. Black Twitter is made up of a diverse group of individuals who hold different experiences. Placing an understanding that the truth behind these racist hashtags can be applied to any member part of Black Twitter would be unethical and should be considered.

Increased Power and Impact

In the past 10 years the user base of Black Twitter has grown significantly and received public recognition from even those not in the Black community. Twitter, which is in its “power stage” by Moor’s definition, has the ability to impact those who directly and indirectly interact with the social company [13]. Based off how Black Twitter chooses to exercise the application, different ethical impacts will be produced as a result. Through their use of racialized hashtags, Black Twitter has leveraged the platform to increase their national impact, specifically crafting dialogues targeted towards racial concerns and injustices affecting their community. In the case of Ferguson, Black Twitter utilized racialized hashtags as part of their activism tactic to demand justice. However, Black Twitter must be cognisant of this power and the ethical implications of how they choose to execute their power and Ferguson is just one context. The cancellation and demise of Paula Deen’s career exemplifies the increased power of Black Twitter and negative impacts a force like Black Twitter can cause. While the cancellation of Paula Deen’s show may be justified in response to her racist and distasteful comments, there are more people than just Paula Deen that suffered the consequences of the cancellation such as her crew, staff, and network. The power and impact Black Twitter garners should be something paid close attention to as more moral and ethical implications arise with the growing user base of Black Twitter.

Emotional Consequences

Black Twitter stands out from other media groups because of their ability to facilitate conversation around social injustices everyone is aware about. However, Safiya Umoja Noble draws attention to how these injustices that circulate on Twitter are rooted deep with emotion pain and contain sensitive content that may trigger individuals. On platforms like Twitter and Facebook, the user is unable to filter content to not show triggering and controversial media and is often bombarded with graphic images of racialized violence which leaves negative socioemotional effects [14]. While Black Twitter is effective at spreading awareness of these injustices, they are also spreading triggering images with severe impacts on the mental and emotional health of those who are subjected to continuous institutional discrimination. [15]

References

- ↑ Picard, A. (2018, March 28). The history of Twitter, 140 characters at a time. Retrieved from https://www.theglobeandmail.com/technology/digital-culture/the-history-of-twitter-140-characters-at-a-time/article573416/

- ↑ Sicha, C. (2009, November 11). What Were Black People Talking About on Twitter Last Night? Retrieved from https://medium.com/the-awl/what-were-black-people-talking-about-on-twitter-last-night-4408ca0ba3d6

- ↑ Brock, A. (2012). From the Blackhand Side: Twitter as a Cultural Conversation. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 56(4), 529-549. doi:10.1080/08838151.2012.732147

- ↑ Sharma, S. (2013). Black Twitter? Racial Hashtags, Networks and Contagion. New Formations, 78(78), 46-64. doi:10.3898/newf.78.02.2013

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Haimson, O. L., & Hoffmann, A. L. (2016). Constructing and enforcing "authentic" identity online: Facebook, real names, and non-normative identities. First Monday, 21(6). doi:10.5210/fm.v21i6.6791

- ↑ Sharma, S. (2013). Black Twitter? Racial Hashtags, Networks and Contagion. New Formations, 78(78), 46-64. doi:10.3898/newf.78.02.2013

- ↑ Vats, A. (2015). Cooking Up Hashtag Activism: #PaulasBestDishes and Counternarratives of Southern Food. Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies, 12(2), 209-213. doi:10.1080/14791420.2015.1014184

- ↑ Brey, P. A. (2012). Anticipating ethical issues in emerging IT. Ethics and Information Technology, 14(4), 305-317. doi:10.1007/s10676-012-9293-y

- ↑ Vats, A. (2015). Cooking Up Hashtag Activism: #PaulasBestDishes and Counternarratives of Southern Food. Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies, 12(2), 209-213. doi:10.1080/14791420.2015.1014184

- ↑ Bonilla, Y., & Rosa, J. (2015). #Ferguson: Digital protest, hashtag ethnography, and the racial politics of social media in the United States. American Ethnologist, 42(1), 4-17. doi:10.1111/amet.12112

- ↑ Shoemaker, David W. “Self-Exposure and Exposure of the Self: Informational Privacy and the Presentation of Identity.” Ethics and Information Technology, vol. 12, no. 1, 2009, pp. 3–15., doi:10.1007/s10676-009-9186-x.

- ↑ Brey, P. A. (2012). Anticipating ethical issues in emerging IT. Ethics and Information Technology, 14(4), 305-317. doi:10.1007/s10676-012-9293-y

- ↑ Noble, Safiya Umoja. “Critical Surveillance Literacy in Social Media: Interrogating Black Death and Dying Online.” Black Camera, vol. 9, no. 2, 2018, p. 147., doi:10.2979/blackcamera.9.2.10.

- ↑ Ibid