Difference between revisions of "Manhunt"

(→Storyline) |

(→Violence) |

||

| Line 35: | Line 35: | ||

===Violence=== | ===Violence=== | ||

| − | The ethical concern and controversy focused on its impression upon children. Its rating did not stop kids from playing since their guardians could buy it for them, either aware or unaware of its contents. When playing, children | + | The ethical concern and controversy focused on its impression upon children. Its rating did not stop kids from playing since their guardians could buy it for them, either aware or unaware of its contents. When playing, children are put into Cash's point of view as he kills many people. Through the entire game they listen to Lionel Starkweather's whispers guiding acts of violence that show how to kill in various methods. The ethical dilemma occurs when impressionable kids are influenced in negative ways by such violence, U.S Representative Joe Baca states, "It's telling kids how to kill someone, and it uses vicious, sadistic and cruel methods to kill,"<ref>Gwinn, Eric. “`Manhunt,' the next Step in Video Game Violence.” Chicagotribune.com, 5 Sept. 2018, www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-2003-11-24-0311240176-story.html.</ref> The game is psychological and introduces players to the choice of kill or be killed; encouraging players to kill since the characters life is on the line.<ref>Muncy, Julie. “Manhunt Remains a Powerful Reflection of Violence on Film.” Wired, Conde Nast, 3 June 2017, www.wired.com/2016/03/manhunt-ps4/.</ref> By killing in gruesome ways, you are rewarded with stars at the end of each level. The player is encouraged to execute in an increasingly brutal way. <ref>Zagal, José P. “Manhunt – The Dilemma of Play.” Well Played 2.0: Video Games, Value and Meaning, by Drew Davidson, ETC Press, 2010, pp. 241–243.</ref> In an experiment searching for the effects of rewarding violent actions in video games, Nicholas Carnagey and Craig Anderson, concluded that playing a violent video game, regardless of whether the game rewards or punishes violence, increases violence and aggression as opposed to playing a nonviolent video game.<ref>Carnagey, Nicholas L., and Craig A. Anderson. “The Effects of Reward and Punishment in Violent Video Games on Aggressive Affect, Cognition, and Behavior.” Psychological Science, vol. 16, no. 11, Nov. 2005, pp. 882–889, doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01632.x.</ref> Children are not able to distinguish that these choices are not ethical in the real world, and only apply in Manhunt's virtual world.<ref>Zagal, Jose P. “Ethical Reasoning and Reflection as Supported by Single-Player Videogames.” IGI Global, IGI Global, 1 Jan. 1970, www.igi-global.com/chapter/designing-games-ethics/50729.</ref> |

[[File:Manhunt5.jpg|200px|thumb|right|Lionel Starkweather's ad for snuff films.]] | [[File:Manhunt5.jpg|200px|thumb|right|Lionel Starkweather's ad for snuff films.]] | ||

Revision as of 21:22, 22 April 2019

| Genre | Survival, Horror |

| Gamming Style | Third-Person |

| Platform | Playstation 2, XBox, Microsoft Windows, Playstation 3, Playstation 4 |

| Release Date | November 18, 2003 - March 22, 2016[1] |

| Developer | Rockstar North |

| Publisher | Rockstar Games |

| Website | MANHUNT-Rockstar Games |

Manhunt is an action, stealth-based, adventure video game developed by Rockstar North, and published by Rockstar Games. The game was originally released for the Playstation 2 game console on November 18, 2003, and was followed by its release for Microsoft Windows and Xbox on April 20, 2004. Manhunt follows the story of James Earl Cash, a criminal who is sentenced to death row. His lethal injection is instead a sedative which allows Lionel Starkweather, a former film director, to leave Cash in Carcer City, where he becomes the star of Starkweather's snuff films. In 2007, Rockstar Games created its sequel Manhunt 2.

Manhunt brought with is a number of ethical issues including issues with violence, voyeurism/surveillance, and gender bias towards men.

Contents

Storyline

The story follows James Earl Cash, a prisoner on death row in line to receive lethal injection. Due to Darkwood's prison's corrupt penitentiary staff, he instead receives a strong sedative[2]. After waking up from the injection, Cash finds himself locked in an empty room, where Liam Starkweather is promptly introduced. Starkweather instructs Cash through a wireless earpiece, telling him to follow his orders if he wants to eventually be set free. He then abandons Cash in Carcer City, a city infested by a gang that Starkweather hired to hunt and kill Cash[3]. As he fights for his life, Cash becomes a one-man star in Starkweather's snuff films, where Cash murders and violently kills the men that are sent to kill him. When Cash finds Starkweather, he kills him with a chainsaw while Starkweather pleas for his life. After Starkweather's death, what took place in Carcer City is exposed by a reporter and covered up by the state. Cash's whereabouts remain unknown at the end of the game[4].

Game Play

Manhunt is played in a third person point of view through the character James Earl Cash. Consisting of 20 levels (called scenes) and 4 bonus levels, the player finds him or herself outnumbered in every level[5]. The map on the lower left hand corner shows the alertness and position of enemies near the player, represented by three different colors. A yellow enemy icon embodies an enemy who is moving around, an orange enemy icon is an enemy that is alerted by Cash's presence, and a red icon is an enemy which has spotted Cash. Anything from walking or running on gravel, to banging on a wall can alert an enemy. The circle on the lower left hand side of the screen shows emanating circles whenever noise is produced by the player.[5] Avoiding running will preserve and increase the player's stamina shown in the lower right hand corner along side their health bar. You can lose health when attacked by an enemy, and can replenish half with "pain killers" found throughout the level.

The stealth mechanics include hiding in the shadows (called the safe zone), and attacking enemies by sneaking up behind them without catching their sight. An enemy cannot spot you in the shadows unless they see you enter. 2 types of weapons can be used for the execution of enemies, one-off weapons and melee weapons; guns can not be used for execution. One-off weapons are those including plastic bags, wire, and glass shards; melee weapons include bats, nightsticks, and a chainsaw.[2] When executing and locking on to an enemy without them being aware there are 3 choices that present themselves: a "hasty", "violent", and "gruesome" kill, yellow, orange, and red respectively.[6] The 3 are presented on the lock-on reticle within 5 seconds of locking onto an enemy, and once one is chosen you can use one of 2 weapons collected throughout the game. A "gruesome" kill leaves cash most vulnerable, and earns the player the highest reward at the end of a level. Movies that earn five star ratings are those with the most brutal kills [2], which unlock bonus levels and concept art. The game can be replayed in 2 different levels ranging in difficulty, fetish being normal and hardcore being most challenging.

Controversy

Controversy with regards to the game peaked in the summer of 2004, with the murder of 14-year-old Stefan Pakeerah. Stefan was murdered by 17-year-old Warren Leblanc, who lured the boy into the woods, beat him with a claw hammer, and stabbed him repeatedly with a knife. Stefan was discovered with 60 separate injuries[7]. Initial media reports claimed that police had found a copy of the game in Leblanc's bedroom, which police had seized as evidence, and Giselle Pakeerah, the Stefan's mother, stated "I think that I heard some of Warren's friends say that he was obsessed by this game. To quote from the website that promotes it, it calls it a psychological experience, not a game, and it encourages brutal killing. If he was obsessed by it, it could well be that the boundaries for him became quite hazy"[8]. Stefan's father, Patrick, added "they were playing a game called Manhunt. The way Warren committed the murder this is how the game is set out, killing people using weapons like hammers and knives. There is some connection between the game and what he has done."[8] Patrick continued "The object of Manhunt is not just to go out and kill people. It's a point-scoring game where you increase your score depending on how violent the killing is. That explains why Stefan's murder was as horrific as it was. If these games influence kids to go out and kill, then we do not want them in the shops."[9] A spokesman for the Entertainment and Leisure Software Publishers' Association (ELSPA) responded to the accusations by stating "We sympathize enormously with the family and parents of Stefan Pakeerah. However, we reject any suggestion or association between the tragic events and the sale of the video game Manhunt. The game in question is classified 18 by the British Board of Film Classification and therefore its copies should not be in the possession of a minor. Simply being in someone's possession does not and should not lead to the conclusion that a game is responsible for these tragic events." [10][11] While the judge in the case found that, "simply being in someone's possession does not and should not lead to the conclusion that a game is responsible for these tragic events",[12] critics have argued its violent content to be problematic, and was once banned in New Zeland from being purchased by anyone[13]. The game was later banned in Australia in 2004, after being available for nearly a years at a M 15+ rating. The game was also banned or refused a classification in Russia, Germany, Saudi Arabia, and South Korea[14]

Ethical Implications

Violence

The ethical concern and controversy focused on its impression upon children. Its rating did not stop kids from playing since their guardians could buy it for them, either aware or unaware of its contents. When playing, children are put into Cash's point of view as he kills many people. Through the entire game they listen to Lionel Starkweather's whispers guiding acts of violence that show how to kill in various methods. The ethical dilemma occurs when impressionable kids are influenced in negative ways by such violence, U.S Representative Joe Baca states, "It's telling kids how to kill someone, and it uses vicious, sadistic and cruel methods to kill,"[15] The game is psychological and introduces players to the choice of kill or be killed; encouraging players to kill since the characters life is on the line.[16] By killing in gruesome ways, you are rewarded with stars at the end of each level. The player is encouraged to execute in an increasingly brutal way. [17] In an experiment searching for the effects of rewarding violent actions in video games, Nicholas Carnagey and Craig Anderson, concluded that playing a violent video game, regardless of whether the game rewards or punishes violence, increases violence and aggression as opposed to playing a nonviolent video game.[18] Children are not able to distinguish that these choices are not ethical in the real world, and only apply in Manhunt's virtual world.[19]

Voyeurism/Surveillance

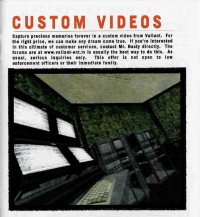

The ethical implication of voyeurism and surveillance is introduced in the storyline. Lionel Starkweather, director of the snuff films, displays voyeuristic tendencies as he watches Cash execute gang members through hidden cameras for his pleasure.[20] Starkweather talks to his victim and affects his actions on occasion; he is not the perfect voyeur.[21] Starkweather's surveillance of Cash holds qualities of Bentham's panopticon, where prisoners are always under the impression that they are being watched.[22] As he watches, Cash is unaware of what will happen to him next and where Starkweather is watching from. Cash is Starkweather's prisoner through constant voyeuristic supervision, and exploited to those looking for snuff films.[2]

Bias towards Men

In video games today, there is a clear distinction in the amount of female protagonists versus male protagonists. Manhunt not only lacks the option of playing as a female, but also lacks female characters in the game in general. The female characters that are depicted include a journalist and the rest are shown as Cash's family members. A quick search of these women brings up pictures of them without proper clothing. Instead they are in revealing shirts and not even wearing pants.

This is a theme seen consistently across video games. In fact, in E3 games, the percentage of female protagonists, across all the video games, ranges from 7-9%[23]. A lack of female protagonists prevents the "normalization of the notion that male players should be able to project themselves onto and identify with female protagonists just as female players have always projected themselves onto male protagonists" [23]. The portrayal of women in video games creates a gender bias that promotes the objectification of women and creates a lack of inclusivity.

References

- ↑ “Manhunt.” PlayStation™Store, store.playstation.com/en-us/product/UP1004-CUSA03512_00-SLUS208270000001?smcid=pdc%3Aus-en%3Aweb-pdc-games-manhunt-ps3%3Awaystobuy-buy-download%3Anull%3A.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 "Manhunt". Valiant Video Enterprises for Sony Playstation 2, 2003. https://www.gamesdatabase.org/Media/SYSTEM/Sony_Playstation_2/manual/Formated/Manhunt_-_2003_-_Rockstar_Games.pdf

- ↑ “Manhunt.” Rockstar Games, www.rockstargames.com/games/info/manhunt.

- ↑ “Manhunt.” IMDb, IMDb.com, www.imdb.com/title/tt0386616/plotsummary.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 “Manhunt - IGN - Page 3.” IGN, IGN, 18 Nov. 2003, www.ign.com/articles/2003/11/18/manhunt-2?page=3.

- ↑ Gwaltney, Javy. “Opinion – Manhunt Is The Dark, Underappreciated Masterpiece We Deserve.” Game Informer, www.gameinformer.com/b/features/archive/2016/03/25/manhunt-is-a-dark-underappreciated-masterpiece.aspx.

- ↑ Britten, Nick. “Teenager Gets 13 Years for 'Video Game' Murder.” The Telegraph, Telegraph Media Group, 4 Sept. 2004, www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/1470929/Teenager-gets-13-years-for-video-game-murder.html.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Store withdraws video game after brutal killing". Daily Mail. July 29, 2004. Archived from the original on 2012-07-16. Retrieved 2012-11-08.

- ↑ David Millward (July 29, 2004). "Manhunt computer game is blamed for brutal killing". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2014-05-20. Retrieved 2012-11-08.

- ↑ Chris Leyton (July 28, 2004). "Manhunt blamed for murder". TVG. Archived from the original on March 14, 2013. Retrieved 2012-11-08.

- ↑ “Manhunt (Video Game).” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 4 Apr. 2019, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Manhunt_(video_game).

- ↑ “UK | England | Leicestershire | Game Blamed for Hammer Murder.” BBC News, BBC, 29 July 2004, news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/england/leicestershire/3934277.stm.

- ↑ Smith, Ed. “Why I Adore the Legendarily Crass, Violent Video Game 'Manhunt'.” Vice, VICE, 28 Mar. 2016, www.vice.com/en_us/article/mvxzyn/why-i-adore-manhunt-the-quintessential-video-game-nasty-210.

- ↑ “List of Banned Video Games.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 11 Apr. 2019, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_banned_video_games.

- ↑ Gwinn, Eric. “`Manhunt,' the next Step in Video Game Violence.” Chicagotribune.com, 5 Sept. 2018, www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-2003-11-24-0311240176-story.html.

- ↑ Muncy, Julie. “Manhunt Remains a Powerful Reflection of Violence on Film.” Wired, Conde Nast, 3 June 2017, www.wired.com/2016/03/manhunt-ps4/.

- ↑ Zagal, José P. “Manhunt – The Dilemma of Play.” Well Played 2.0: Video Games, Value and Meaning, by Drew Davidson, ETC Press, 2010, pp. 241–243.

- ↑ Carnagey, Nicholas L., and Craig A. Anderson. “The Effects of Reward and Punishment in Violent Video Games on Aggressive Affect, Cognition, and Behavior.” Psychological Science, vol. 16, no. 11, Nov. 2005, pp. 882–889, doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01632.x.

- ↑ Zagal, Jose P. “Ethical Reasoning and Reflection as Supported by Single-Player Videogames.” IGI Global, IGI Global, 1 Jan. 1970, www.igi-global.com/chapter/designing-games-ethics/50729.

- ↑ “Manhunt: The Story - IGN - Page 2.” IGN, IGN, 30 Sept. 2003, www.ign.com/articles/2003/09/30/manhunt-the-story?page=2.

- ↑ Doyle, Tony. “Privacy and Perfect Voyeurism.” Ethics and Information Technology, vol. 11, no. 3, 2009, pp. 181–189., doi:10.1007/s10676-009-9195-9.

- ↑ McMullan, Thomas. “What Does the Panopticon Mean in the Age of Digital Surveillance?” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 23 July 2015, www.theguardian.com/technology/2015/jul/23/panopticon-digital-surveillance-jeremy-bentham.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Petit, Carolyn, and Anita Sarkeesian. “Gender Breakdown of Games Featured at E3 2018.” Feminist Frequency, 14 June 2018, feministfrequency.com/2018/06/14/gender-breakdown-of-games-featured-at-e3-2018/.